Evaluating Crime Prevention through Social Development Projects: Handbook for Community Groups

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Module 1: An overview of evaluation Learning objectives

- Module 2: Setting the stage – Preparing a logic model Learning objectives

- Step 1: Identify project goals (outcomes) and who you intend to serve

- Hints for developing project goals

- Goals/Outcomes: Indicating the direction of change

- What's next? Project components, inputs, activities, & outputs

- Splash & ripple

- What is a logic model?

- Why develop a logic model?

- The logic model

- Logic model check list

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Suggested resources

- Module 2 worksheets

- Module 3: Developing an evaluation plan Learning objectives

- What have we got so far?

- What's next?

- What should an evaluation plan include?

- Identifying evaluation questions

- Identifying indicators

- How to choose good indicators

- Some additional considerations when choosing indicators

- Identifying information sources

- Choosing data collection methods

- Deciding whether to sample

- Choosing a sample

- Deciding how many to include in a sample

- Analyzing the results

- Reporting the results

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Suggested resources

- Module 3 worksheets

- Module 4: Data collection methods Learning objectives

- What is "data"?

- Official sources

- Surveys

- Survey tips

- What is wrong with these questions?

- Standardized tests

- Testing tips

- In-depth interviews

- Interview tips

- Focus groups

- Focus group tips

- Observation

- Observation tips

- Multiple methods

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Suggested resources

- Answer key

- Module 4 worksheets

- Module 5: Evaluation designs Learning objectives

- What is evaluation design?

- Levels of evaluation

- Threats to the validity of evaluation results

- Evaluation design

- Design #1: Single group posttest only

- Design #2: Single group pre- and posttest

- Design #3: Comparison group posttest only

- Design #4: Comparison group pretest and posttest

- Design #5: Time-series designs

- A word about comparison groups

- Further words of caution

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Suggested resources

- Answer key

- Module 5 worksheets

- Module 6: Analyzing data/reporting results Learning objectives

- The art of interpreting data

- The science of analyzing data

- Key steps in data analysis

- Analyzing results

- Standardized tests

- Qualitative data

- Reporting your results

- Questions to consider in your report

- Match your presentation style to your audience

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Suggested resources

- Module 6 worksheets

- Module 7: Evaluation challenges and solutions Learning objectives

- Challenge #1: Getting buy-in

- Challenge #2: Participant involvement

- Challenge #3: Data collection

- Challenge #4: Realistic outcomes

- Challenge #5: Data analysis

- Challenge #6: Finding an evaluator

- Challenge #7: Ethical considerations

- Challenge #8: Reflecting community and cultural differences

- What other evaluation challenges come to mind?

- Resources and supports

- Glossary of terms

- References

- Suggested resources

- Module 7 worksheets

- General resource list

- Community/crime prevention resources

Acknowledgements

Evaluating Crime Prevention through Social Development Projects was developed as part of a train-the-trainer program to equip program staff at the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC) with the knowledge and resources needed to encourage and enhance the evaluation capacity of community groups involved in crime prevention through social development projects.

The Trainer's Guide and accompanying Handbook for Community Groups were developed by Mary Sehl, Senior Evaluation Analyst, National Crime Prevention Centre. As with most projects, this project could not have happened without the advice and support of many others. Special thanks are due to Colleen Ryan, now with Health Canada, for identifying the need for this initiative and to members of the project's advisory committee for their valuable direction:

- Linda Casson Hare, Senior Program Officer, Yukon

- Susan Howe, Senior Evaluation Analyst, Vancouver

- Dianne MacDonald, Program Manager - Saskatchewan

- Monika Ochnik, Program Officer - Ontario

- Wayne Stryde, Director Program Development and Delivery, Ottawa

- Michelle Woods, Program Officer, Thunder Bay

Special thanks are also due to Brin Sharp, whose training and advice in adult education techniques are reflected throughout the Trainer's Guide, and to Susan Howe for the energy and support she brought to this initiative and for her help in planning and cofacilitating a pilot training session in Vancouver. Her creativity is reflected in many of the exercises used in the training workshops.

Thank you also to all members of the NCPC evaluation unit for their comments and advice on the training package and for the energy they have brought to delivering the training to NCPC program staff. Particular thanks go to Muguette Lemaire, Senior Evaluation Analyst, Montreal, for her extensive help with the French version of the Trainer's Guide and Handbook for Community Groups and to Carolyn Scott for taking a lead role in planning the evaluation of this initiative. Tim Peters, Antoine Bourdages and Wayne Stryde also deserve much appreciation for their direction and ongoing support for this project as members of NCPC's management team.

Mary Sehl

Senior Evaluation Analyst

NCPC

Why evaluation training?

- To encourage and enhance the evaluation capacity of project sponsors

- To provide supports and resources to facilitate evaluation efforts

- To establish processes and benchmarks for the evaluation of funded projects

The National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC) sees evaluation as a tool for project management and learning. Evaluation is not done simply to prove that a project worked, but also to learn about and improve the way it works.

Community groups interested in applying for NCPC funding to support their crime prevention through social development project will be expected to play different roles in evaluation depending on the stream of funding they receive.

Projects funded through the Crime Prevention Action Fund (CPAF) develop innovative ways to prevent crime. The CPAF helps people working at the ground level undertake activities that deal with the root causes of crime. It aims to build partnerships between sectors such as policing, community health and voluntary and private sectors to enhance community capacity to prevent crime through social development. It helps community groups, to make their crime prevention efforts more sustainable, and to increase public awareness and support for crime prevention activities.

Projects funded under CPAF conduct evaluations to:

- See how the project is doing on a day-to-day basis (on-going monitoring);

- See if the project is on track to meet expected outcomes (results), if it is on time, and if it is using resources as planned mid-way through the project (mid-term evaluation);

- See if the overall changes it was trying to achieve actually happened by the end of the project (final evaluation).

The Policing, Corrections and Communication Fund (PCCF) supports projects where community partners work together to prevent crime primarily through social development. It is intended for law enforcement agencies, community corrections groups/organizations, Aboriginal communities, community-based organizations and the municipalities in which they work.

If you have received or are interested in funding though the Crime Prevention Action Fund, or the Policing, Corrections and Communication Fund , this training will help to improve your ability to develop a sound project plan and to conduct a credible evaluation.

The Research Knowledge and Development Fund (RKDF) supports a range of research activities, demonstration projects, knowledge transfer initiatives and evaluations that identify and analyze gaps in the current body of knowledge related to crime prevention in Canada; create new knowledge in areas where gaps have been identified; synthesize the results of existing research; and contribute to a growing awareness and recognition of promising practices and models for community-based crime prevention. Projects are intended to demonstrate what works and what is promising in reducing the risk factors associated with crime and victimization. Third-party evaluators are hired to conduct rigorous evaluations of these projects in order to identify the costs, benefits, and overall effectiveness of innovative efforts to prevent crime.

Project management and staff will work closely with the third-party evaluator, and in most cases will be involved in the collection of information for the evaluation. If you are interested in the RKDF, this training is an important way to improve your understanding of evaluation and your ability to work with an evaluation contractor.

For more information about NCPC funding programs, see the National Crime Prevention Strategy web site www.publicsafety.gc.ca/ncpc

Organization of this Handbook

This Handbook is organized into seven chapters that correspond to the seven modules of the Crime Prevention through Social Development Evaluation Training package. The end of each chapter provides a glossary of terms used in the chapter and a list of resources relevant to the topics covered. Worksheets used in the training sections are provided at the close of each chapter.

We hope you find the handbook a helpful reference during the training sessions and long after you have completed them. We encourage you to make use of the resources in the resource section of each chapter as you plan evaluations of your crime prevention projects.

Module 1: An overview of evaluation

Learning Objectives

- Understand some of the barriers to community-based evaluations

- Understand how evaluation can improve project management and delivery

- Learn what evaluation is...

- Major approaches

- Basic steps

- Know when to bring in professional evaluators

Why should we care about evaluation?

If we care about preventing crime and victimization in Canadian communities, it only makes sense to care about what works in reducing crime and victimization. The only way to know this for sure is to invest in evaluation.

Why don't we evaluate?

Time

We know that time is especially a problem for community groups that are operating on shoestring budgets. It takes time to plan an evaluation, implement it, analyze data, report the results, and review their implications for project activities. The good news is that much of this work is part of good project management and can be integrated into daily activities.

Money

You may feel that the costs devoted to evaluation could be better spent on project activities. It is true that, at a minimum, evaluation requires costs in staff time. Rigorous third-party evaluation can cost a lot more. Local university or college faculty members and students can sometimes provide free help as part of student internships or projects.

Expertis

Your group may have little experience in planning projects that are eligible for government funding. We hope to show you how the knowledge and skills needed to plan projects are similar to those needed to plan evaluations.

Evaluation has a reputation for being complex and requiring outside expertise. While sometimes expertise is needed to conduct statistical analyses or to help determine how to answer evaluation questions, simpler evaluations can be done in-house. We'll talk more about this in this section of your handbook.

Intrusiveness

To answer questions like "Who are we reaching?" or "Did the project result in changes in attitude or behaviour," evaluations ask questions about people's life experiences, their attitudes and behaviours.

We have found that project staff are often more concerned about the intrusiveness of these questions than are the participants in their projects. It is important to remember that participation in an evaluation should always be voluntary. Participants should always be told they can refuse to answer questions or can end their participation in the evaluation at any time without affecting their involvement in project activities.

We already know the project is effective

You probably have a lot of stories or anecdotes that have proved to you the effectiveness of the project you are planning. You might feel this is more than enough evidence to prove the planned activities are effective. Evaluation helps to provide an evidence base so others can also be convinced.

Philosophy

You may feel the work you do cannot be quantified in numbers or described in a simple "linear" way. Projects often have many parts. They can affect participants in subtle, unanticipated ways. It's true that evaluations sometimes fail to capture the complexity of project activities and the ways in which they work. Adding evaluation questions that give participants and staff an open place to tell their stories can ensure these aspects are captured.

Long-term change vs. short-term funds

It seems contradictory. On the one hand, the National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC) provides funds for only a short time; on the other, it recognizes that change often takes a long time to occur. While it's ideal to be able to track change over the long term, if you can make strong arguments as to why the short-term outcomes of your project are likely to lead to long-term change, you can focus on measuring the short-term changes and don't need to track change over the long term.

This Handbook for Community Groups and the accompanying training sessions will show you how to develop a logic model. A strong logic model that shows how project activities will lead to short- and long-term outcomes and how they all link together demonstrates to others how the short-term changes your project accomplishes can lead to further changes long after the project ends.

Fear

It's natural to worry that a negative evaluation might mean your group will not be able to get further funding. But projects often get better as a result of evaluations that show how some of their results could be improved. Evaluation is a good way to show funders you are interested in continuous improvement.

Why evaluate?

Decision making, managing the project

Evaluation is part of good management. It doesn't have to involve a lot of time or money, but some time and some money should be devoted to evaluation if you want to manage your project effectively. How ambitious your evaluation will be is likely to depend on the size and budget of your project.

You are probably already doing some kind of evaluation, at least in informal ways. You might be asking questions about participant satisfaction. Or you might be assessing the need for additional staff.

Evaluation can answer questions that need to be answered in order to ensure good project management. For example, you might ask:

- Are we reaching who we intended to reach or are we missing the people who most need our project?

- Do we need more project staff?

- Do project staff need more training?

- Does the project ensure the safety of staff and/or participants?

- Is the project resulting in the changes we thought it would?

- What aspects of the project should be modified, expanded, continued, or discontinued?

Project improvement

If your group has been involved in other community projects, you have probably made changes to improve aspects of these projects over time. For example, you may have changed the location or time in order to improve access. You may have engaged a new partner to increase referrals. You may even have evaluated these changes to learn if they made a difference. Documenting what worked can help others to learn from your project. It can help to improve not just your project, but also other projects in your community or across Canada.

Did the project work?

If we really care about crime prevention, we'll want to know that what we do works. After all, why invest our time and money in something that, in the end, isn't making a difference?

If it's hard to document whether a project prevents crime or reduces victimization, we can often show how it reduces factors associated with crime and victimization (risk factors) or increases factors that help to prevent crime or to reduce victimization (protective factors). We'll also want to know how it works so that others can copy it.

Unanticipated outcomes

Sometimes projects have effects we never predicted. These can be good or bad. For example:

-

Good. Parenting projects intended to improve participants' knowledge of child development and good parenting practices sometimes have the unintended effect of increasing participants' social support network. Through the project, they get to know others in their community whose children are the same age. They provide each other with emotional support and sometimes they provide concrete supports such as help with childcare or information about drop-in projects in the neighbourhood.

-

Bad. An evaluation of an early intervention support group intended to reduce alcohol and drug use among students (Deck & Einspruch, 1997, cited in Einspruch & Deck, 1999) found the program had some unanticipated negative outcomes. Students using alcohol or other drugs were invited to participate in a support group intended to help them examine their substance use and related behaviours, improve their problem-solving and communication skills, and develop positive bonds with others. The evaluation found students who participated in the program to a "satisfactory" level were one and a half times more likely to report alcohol use at the end of the school year than those who were referred but refused participation or who did not actively participate.

It's important to remember that projects with the very best of intentions can cause harm. In cases like the one cited above, projects might actually result in poorer outcomes for participants. Another form of harm involves tying up people's time in projects that don't have any impact when we could redirect their time and public money toward projects that have greater impact.

Accountability

Taxpayers want to know their money is spent wisely. Government needs to be accountable for the dollars it spends on community projects. Failure to document whether these projects make a difference results in questions from the Auditor General, politicians, and ultimately, fellow Canadians.

Too often we forget that we also need to be accountable to participants in community projects. They deserve to have the opportunity to express their views about what works or doesn't work and to learn from evaluation reports about the ability of programs to achieve their intended outcomes. Front-line staff often express concerns that evaluations ask too many questions of participants and that these questions are too intrusive. These are legitimate concerns. But we often find that when participants are approached in a positive way and given an overview of the purpose of the evaluation and their role in it, they are excited about their role as "research assistants." They are interested in "what works."

Public relations/fundraising

Strong project results are the best tool to promote your project and to encourage others to donate money or provide resources to sustain it.

What is evaluation?

- It's a process by which we determine whether a project is meeting its goals through the activities taking place and in the manner expected.

- It summarizes:

- Why we developed the project (goals)

- What it involves (project activities)

- What we expect will happen as a result of these activities (anticipated results or outcomes)

- What in fact did happen (actual results or outcomes)

- What this information tells us about the project (conclusions) (Ottawa Police Services, 2001, p. 14)

Evaluations do not necessarily do all of the things listed above. Some focus more specifically on reviewing the project's development and examining project activities to assess whether the project is being offered in the way it was intended (process evaluation). Others focus more on the last three points and assess whether the project achieved its intended outcomes (outcome evaluation).

Types of evaluation

Needs assessment

A needs assessment is used to learn what the people or communities that you hope to reach might need in general or in relation to a specific issue. For example, you might want to find out about safety issues in your community, about access to services, or about the extent to which your community is dealing with a certain type of crime or a certain form of victimization.

Resource assessment

A resource assessment is used to assess the resources or skills that exist among the people or communities with which you hope to work. It is often conducted alongside a needs assessment. Resource assessments identify the skills that community members can contribute to a project and resources such as community space, in-kind and financial donations, volunteer time, and other attributes that can be tapped by your crime prevention project.

Evaluability assessment

An evaluability assessment is done to determine whether a project is ready for a formal evaluation. It can suggest which evaluation approaches or methods would best suit the project.

Project monitoring

Project monitoring counts specific project activities and operations. This is a very limited kind of evaluation that helps to monitor, but not assess the project.

Formative

Also known as process evaluation, a formative evaluation tells how the project is operating, whether it is being implemented the way it was planned, and whether problems in implementation have emerged (for example, it might identify that a project is reaching a less at-risk group than it intended, that staff do not have the necessary training, that project locations are not accessible, or that project hours do not meet participant needs.).

Outcome

An outcome evaluation examines the extent to which a project has achieved the outcomes it set at the outset.

Summative

Summative evaluations examine the overall effectiveness and impact of a project, its quality, and whether its ongoing cost can be sustained.

Cost-effectiveness

A cost-effectiveness study examines the relationship between project costs and project outcomes. It assesses the cost associated with each level of improvement in outcome.

Cost-benefit

Cost-benefit analysis is like cost-effectiveness analysis in that it looks at the relationship between project costs and outcomes (or benefits). But a cost-benefit study assigns a dollar value to the outcome or benefit so that a ratio can be obtained to show the number of dollars spent and the number of dollars saved. A well-known cost-benefit analysis was done of the Perry Preschool initiative in the United States. It concluded that for every one dollar spent, more than seven dollars were saved (Barnett, 1993, cited in Schweinhart, 2002).

Some major approaches

External evaluation

This approach employs an external evaluator (a third party or person/organization not previously associated with the project being evaluated) to conduct the evaluation. Using an evaluator who is not part of the organization being evaluated increases the perceived objectivity of the results. External evaluators may be used in all of the approaches described below. Outside contractors are often hired to facilitate participatory or empowerment evaluations.

Utilization-focused

This approach focuses on what project managers and staff need to know to assist with project decision making and improvement.

Participatory

This is a method that involves participants in all aspects of the evaluation, from identifying the evaluation questions to deciding what information to collect, how to do it, and how to interpret the findings.

Empowerment

This is an approach that uses evaluation concepts, techniques, and findings to help community groups improve their programs and services. The evaluator acts as a coach or facilitator to help project staff and participants through a process of self-evaluation and reflection. Empowerment evaluation follows three steps: a) establishing a mission or vision statement, b) identifying and prioritizing the most significant program activities and rating how well the program is doing in each of those activities, and c) planning strategies to achieve future project improvement goals (Fetterman, 2002).

The approach you choose for your evaluation will depend on the evaluation's purpose. If you wish to learn ways to improve the services you offer, a utilization-focused or an empowerment approach might be appropriate. If you want to convince outside organizations that you are having a positive impact on participants, an external evaluator will help to assure objectivity.

| Steps | STOP fraud against seniors project |

|---|---|

| Identify goals (anticipated outcomes) |

|

| Describe the project | Project Activities:

|

| Identify what you want to know (evaluation questions) |

|

| Identify data sources and data collection tools |

|

| Collect the information | Student interns will assist with data collection |

| Organize the information | Contractor will enter data into database |

| Analyze the data | Contractor will analyze data for:

|

| Report the results, identify next steps |

|

When to bring in evaluation professionals

Community groups often think evaluation requires the services of an expert outsider. While expert help is sometimes needed, it's not always required. Projects funded under the Crime Prevention Action Fund (CPAF) often manage their evaluations themselves. Some choose to contract with an outside evaluator on a short-term basis to undertake key activities. For example, they may hire an evaluator to help them identify or develop appropriate data collection instruments, to develop a database, or to analyse evaluation data.

Projects funded under the Research and Knowledge Development Fund (RKDF), on the other hand, always rely on outside evaluators to ensure a rigorous and objective assessment of their project's effectiveness.

This series of workshops is intended to help you to better understand the basic steps of evaluation. We hope you'll see evaluation as an ongoing part of good project management.

Of course, there are times when you will not have the evaluation knowledge or the time and resources needed to conduct your own evaluations. Here are some situations in which an outside evaluator might be useful:

- When complex statistics are needed to analyze the results of your evaluation

- When you plan to use a wide variety of information-gathering methods, requiring detailed comparison and analysis

- When evaluation data are obtained at different points in time and you wish to analyze them to see what changes have occurred and why

- When you are unsure what information is needed to answer your evaluation questions

- When your evaluation involves experimental and comparison groups, requiring different levels of statistical comparison

- When you want an objective viewpoint (Ottawa Police Services, 2001, p. 21).

If you decide to hire an external evaluator, think about using your time with the evaluator as a learning opportunity. Consider adding to the evaluator's contract a requirement that he or she prepare you to use evaluation as an ongoing practice to manage your project effectively.

Glossary of terms

Analyze (data)

Analyzing data involves bringing some sense or meaning to the information you have collected. In the case of qualitative data, this might involve categorizing the information you collected into themes that summarize what was said. In the case of quantitative data, descriptive statistics and, in some cases, statistical tests are used to provide meaning to raw numbers. This might involve, for example, identifying the mean or average response, the range of responses from highest to lowest, or the statistical likelihood that a change in scores over time is due to more than just chance. More information about analyzing data is provided in Module 6 of this Handbook.

Comparison (or control) group

Community-based research refers to a comparison group as opposed to a control group, the term more often used in experimental research. A comparison group is a group of participants who have similar characteristics to participants in the program or project being evaluated, but who do not receive exposure to the project activities.

Data

Data is another word for information that is collected to provide knowledge or insight into a particular issue.

Evaluability assessment

An evaluability assessment is way of assessing whether a project is ready for a formal evaluation. It can suggest which evaluation approaches or methods will best suit the project.

Experimental group

An experimental group is a group of people who participate in an intervention (or program). The results for this experimental group can be compared to those of a comparison group who do not receive the intervention. The comparison group should have similar characteristics to those of the experimental group, except that they do not receive the intervention under study. The difference in results between the two groups is then measured.

Formative evaluation

Formative evaluation assesses the design, plan, and operation of a program. It reports on whether the project is being implemented the way it was planned and whether problems in implementation have emerged.

Logic model

A logic model is a way of describing a project or program. It is a tool to help in project planning and evaluation. A logic model describes the resources and activities that contribute to a project and the logical links that lead from project activities to the project's expected outcomes. Logic models are often depicted as a flow chart that includes the project's inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes.

Needs assessment

A needs assessment is a way to collect and analyze information about the needs of local communities or groups in general or in relation to specific issues.

Outcome evaluation

Outcome evaluation assesses the short and long-term outcomes that result from participation in a project or program.

Pre-post testing

Pre-post testing involves administering the same instrument before and after an intervention or program.

Process evaluation

A process evaluation reviews project development and examines project activities to assess whether the project is being offered in the way it was intended and to identify areas where project administration and delivery can be improved.

Random sample

A random sample is made up of individuals who have an equal opportunity of being selected from a larger population. Whether any one individual from the larger population is selected for the sample is determined by chance.

Resource assessment

A resource assessment is used to assess the resources or skills that exist among the people or communities with which a project plans to work.

Sample

A sample is a subgroup of a larger population. It is studied to gain information about an entire population.

Summative evaluation

A summative evaluation examines the overall effectiveness and impact of a project, its quality, and whether its ongoing cost can be sustained.

References

Einsprunch, E.L., & Deck, D.D. (1999, November). Outcomes of peer support groups. Retrieved March 16, 2004, from

http://www.rmcorp.com\Project\PIeval\Peer.pdf

Fetterman, D. (2002). Collaborative, participatory, and empowerment evaluation. Retrieved March 16, 2004, from

http://www.stanford.edu/~davidf/empowermentevaluation.html

Ottawa Police Services. (2001, August). You can do it: A practical tool kit to evaluating police and community crime prevention programs. Retrieved March 16, 2004, from http://dsp-psd.communication.gc.ca/ Collection/J2-180-2001E.pdf

Schweinhart, L.J. (2002, June). How the High/Scope Perry Preschool study grew: A researcher's tale. Phi Delta Kappa Center for Evaluation, Development, and Research, Research Bulletin No. 32. Retrieved March 16, 2004, from

http://ww.highscope.org

Suggested resources

Websites

Bureau of Justice Assistance Evaluation

Evaluation Strategies for Human Services Programs

http://www.bja.evaluationwebsite.org/html/documents/evaluation_strat

This website provides a "Road Map" which answers the following questions: What is evaluation? Why do we conduct evaluation? What types of programs are evaluated? When do we evaluate?

Centre for Substance Abuse Prevention

Prevention Pathways

http://pathwayscourses.samhsa.gov/samhsa_pathways/courses/index.htm

This website offers free tutorials on various evaluation topics. "Evaluation for the Unevaluated 101," is an excellent introductory course to evaluation that addresses the main components of evaluation and why evaluation is important.

United Way of America

Outcome Measurement Resource Network

http://www.unitedway.com

This website is a good starting point to learn the basics of outcome measurement. It includes an introduction to outcome measurement and a discussion of why it is important.

Guides and Manuals

Annie E. Casey Foundation

When and How to use External Evaluators

http://www.aecf.org/publications/data/using_external_evaluators.pdf

This publication reports on various issues related to hiring an external evaluator. It includes questions to use when interviewing external evaluators and suggestions for managing evaluation contracts.

Health Canada

Guide to Project Evaluation: A participatory Approach

http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/ph-sp/phdd/resources/guide/index.htm

Chapters One and Two of this guide provide a basic introduction to evaluation. The remainder of the guide provides useful advice for data collection, analysis, and reporting.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services - Administration for Children and Families

The Program Manager's Guide to Evaluation http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/other_resrch/pm_guide_eval/reports/pmguide/pm guide_toc.html

The Program Manager's Guide consists of nine chapters that address the purpose of evaluation and its main components. An additional feature of this guide is a discussion about hiring and managing external evaluators.

W.K. Kellogg Foundation

Evaluation Handbook

http://www.wkkf.org/Pubs/Tools/Evaluation/Pub770.pdf

This handbook introduces evaluation as a practical and useful tool, and assists the user in creating a blueprint of evaluation.

Textbooks

Research Methods Knowledge Base

Introduction to Evaluation

http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/

This on-line textbook introduces the user to evaluation, its basic definitions, goals, methods, and the overall evaluation process. It includes answers to frequently asked questions about evaluation.

Newsletter

Centre for Community Enterprise

Making Waves, "The 'Who' Of Evaluation," Vol. 11, No.2.

http://www.cedworks.com/waves03.html

This article addresses the issues involved in using an outside evaluator and recommends use of a combination of internal and external expertise.

Module 1 Worksheets

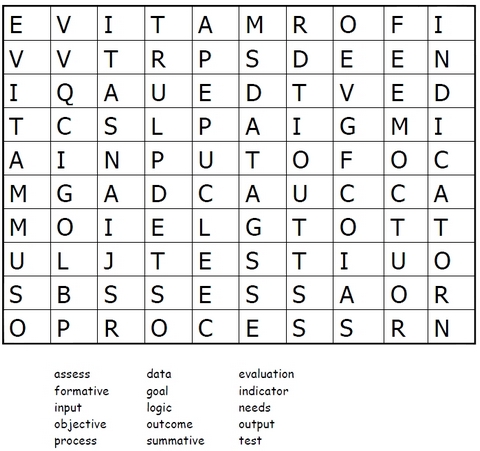

Worksheet #1

What is in a name? How many evaluation terms can you find?

Worksheet #2

Why should we care?

Why should we care about crime prevention in your community?

Module 2: Setting the stage for evaluation – Preparing a logic model

Learning Objectives

- Ability to design good projects

- Ability to design projects that are "evaluable" (i.e., that can be evaluated)

- Ability to develop strong project goals and outcomes

- Understanding of the parts of a logic model

- Ability to develop a logic model

Step 1: Identify project goals (outcomes) and who you intend to serve

A good project plan clearly identifies your goals or outcomes and the population you plan to serve. It tells others where you are headed. (In keeping with the planning tools included in the application guide for the Crime Prevention Action Fund , we're using the words "goals" and "outcomes" interchangeably.)

| Step 1 | Examples |

|---|---|

| Goals (anticipated outcomes) – What you expect the project to accomplish or change |

|

| Priority group – Who you intend to serve |

|

This is the first step in presenting the project's logic.

This training module shows how to develop a project plan, which will also serve as the first part of the evaluation plan. The two fit together. In the next training module, we will explain how to develop the rest of the evaluation plan.

Your knowledge of community needs and resources will help you to identify the goals of your project and the group of people it will serve. It is best to base your knowledge of community needs and resources on an objective assessment. You may already be familiar with needs assessments and resource assessments. These are research and project management tools that can help you plan your project. We have included some resources on needs assessments at the end of this chapter.

If you represent an agency or service that is planning a project, be sure to include members from the community you hope to serve at the project planning stage. You will want to know:

- What are their crime prevention goals?

- What would they like to see changed?

- Who do they think the project should reach out to?

Bringing together human service agencies and community members to discuss their unique perspectives can result in a stronger project.

When you bring everyone together, we suggest you give them hints about writing good project goals. We've listed some below.

Hints for developing project goals

- Use action words like increase, reduce, improve

- Avoid words like provide, develop, create

Saying that a project goal is "to provide recreational opportunities" does not tell us anything about the purpose of those recreational activities or the changes they are expected to bring about. Programs are developed to make change. They are not developed simply for the sake of delivering products or services alone.

Saying that these recreational opportunities are going to increase teamwork and leadership skills or reduce vandalism in the after-school hours are what we call SMART goals.

Be SMART

Specific

Is the goal/outcome specific? Is it clear? If you want to increase community safety, specify the particular changes you are trying to achieve to increase safety. Mention the particular group you are targeting – such as seniors, children or youth – and the particular issue you are trying to change. Here are some sample goals related to community safety:

- Increase the use of "walking school buses" for children who walk to and from the local elementary school

- Increase after-school programs for latch-key children

- Increase the participation of rural youth in organized recreational activities.

Measurable

Will you be able to measure (see) change? Will you be able to answer whether or not you achieved your goal? For example, how would you measure "improved partnerships"? Consider rewriting this goal to specify what changes will take place. Here are some examples that are easier to measure:

- Increase opportunities to share resources

- Reduce overlap in services

- Increase knowledge of community crime prevention resources

Achievable, attainable

Will the project be able to achieve the outcomes it set out? It may not be realistic to set "reduced crime" as a goal or outcome if the project activities focus on increasing coordination of services or improving awareness of a particular issue.

Relevant, realistic

Does the goal mean something to people involved in the project? Be realistic about what you can do, keeping in mind the resources available to you.

Trackable, timely

Don't set long-term goals for a short-term project. Focus on something that can be completed within the project period.

Goals/Outcomes: Indicating the direction of change

Here are some examples of the kinds of words that goals or outcomes should include. They are action words that indicate the direction of change – that is, whether something will be reduced or increased.

- Alleviated

- Augmented

- Decreased

- Diminished

- Enhanced

- Enlarged

- Expanded

- Extended

- Improved

- Increased

- Lowered

- Prevented

- Raised

- Reduced

- Shortened

What's next? Project components, inputs, activities, & outputs

Now that you have completed Step 1, you can fill in the remaining steps to complete your project plan. These steps are sandwiched between the priority group and the achievement of your goals or final outcomes. They show how you will accomplish the goals you have set. They are the key components of your project's logic model. Each step naturally leads to the next. Although the outcomes come last in the logic model, they are identified up front in order to show where we're headed.

Logic model

Splash and Ripple

Take a look at the Splash and Ripple Primer located at: http://www.ucgf.ca/English/Downloads/RBMSept2003.pdf (PLAN:NET Ltd., 2003).

It provides a wonderful metaphor to help you remember the key components of a logic model and how they fit together.

It talks about a person standing over a pond and holding a rock. When the person drops the rock in the pond, it creates a splash and then a series of ripples. If we liken this image to the steps in developing a project plan or logic model:

- The rock dropping into the pond is like an input

- The splash is like an output

- As the ripples spread, they are like moving from short-term to intermediate, and eventually to long-term outcomes

Control decreases as the ripples spread, just as it does as we move toward longer-term outcomes. Influences other than the project are more likely to intervene as time passes. We can contribute toward the longer-term outcomes, but we can rarely control them.

What is a logic model?

A logic model is a way of describing a project. It describes what goes in and out of your project. It answers questions in five areas:

- Inputs – What resources are needed to make your project operate (e.g., equipment, project materials, transportation costs, staff resources)?

- Activities – What activities take place in the project?

- Outputs – How much and what kind of products or services are generated from these activities (e.g., the number of participants involved, the number of sessions or workshops, the number of promotional materials distributed)?

- Outcomes – How well were the activities carried out and did they do what they were expected to do? Outcomes occur in the short term, intermediate, and long term. Long-term outcomes are sometimes called "impacts"

- Impact (or long-term outcome) – Has the project had an effect and, if so, was it positive, negative, or somewhere in between? These are the "big-picture" changes that the project is working toward; they are similar to the original goal statement.

Some sample outcomes :

Short term

- Increased after-school activities

- Improved coordination of services for youth, and

- Increased involvement of youth in planning activities

Intermediate

- Increased access to recreation

- Increased leadership skills

- Increased involvement in community events

Long term (impact)

- Increased sense of community

- Reduced vandalism and petty

Why develop a logic model?

- Project planning – Logic models are a useful tool for visioning and priority-setting exercises. They are a good way to bring project staff, managers, and partners together to identify what they hope to accomplish and what activities they will undertake.

- Monitoring and evaluation – Logic models help evaluators to assess the evaluability of a project (the extent to which the project activities are logically linked to the original goals, the soundness of the logic, and the extent to which the anticipated outcomes are realistic and measurable). The logic model provides a starting point for the development of project performance measures and ongoing monitoring.

- Communication, promotion – Logic models provide a simple picture of what programs do and what they plan to accomplish. They ensure all players communicate the same message when describing a project and its purpose to senior managers, referral sources, participants, and media.

- Orientation and training – Logic models provide a "big-picture" overview for new staff or volunteers

- Grant applications – Logic models are excellent tools for describing programs to potential funders. Their use in a grant application shows the funder the project has taken the first steps to putting an accountability structure in place.

Because your project is likely to change as a result of all kinds of influences, you should review your logic model regularly to ensure it continues to reflect your project's goals, activities, and anticipated outcomes.

The logic model

The logic model shown on the previous page is just a sample of what a logic model might look like. Logic models can be depicted in chart form, as on Worksheet #3, or as a flow chart, as show on the previous page.

The flow chart helps to show how various parts of the logic model link together. These links are an important part of the logic model. They show the logic between the different parts of the project. You should have a rationale to explain why each activity you plan is likely to lead to a particular outcome or outcomes. If a combination of activities result in a particular outcome, the lines in the flow chart should reflect that logic.

The following checklist can help you check how well you're doing in preparing your logic model.

Logic model check list

- Do the outcomes represent changes, benefits, results, or impacts of the project?

- Do the outcomes include strong verbs and reflect the direction of change?

- Are each of the long-term outcomes connected to short-term or intermediate outcomes that lead to them?

- Are the short-term/intermediate outcomes within the control of the project and within the usual time frame for evaluation?

- Is it reasonable to expect, based on previous experience or research (an evidence base), that these intermediate outcomes will lead to the long-term outcomes identified?

- Is there at least one activity that specifically addresses each short-term outcome?

- Is it realistic to expect that the outcomes listed could be achieved given the activities proposed? Should additional activities be added? Should the intensity, duration, or nature of the activities be changed? Or, should the outcomes be rethought?

- Are all of the program activities necessary? For example, are there any activities that do not lead to any outcomes? Are there some outcomes with too many activities linked to them?

Glossary of terms

Evaluability assessment

An evaluability assessment is way of assessing whether a project is ready for a formal evaluation. It can suggest which evaluation approaches or methods would best suit the project.

Input

Inputs refer to the resources invested in the delivery of a program or project. Sample inputs include funding, human resources (both paid and volunteer), equipment, or services. Inputs may be funded through a project budget or provided in-kind by project partners or volunteers.

Logic model

A logic model is a way of describing a project or program. It is a tool to help in project planning and evaluation. A logic model describes the resources and activities that contribute to a project and the logical links that lead from project activities to the project's expected outcomes. Logic models are often depicted as a flow chart that includes the project's inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes.

Needs assessment

A needs assessment is a way to collect and analyze information about the needs of local communities or groups, either in general or in relation to specific issues.

Output

Outputs refer to the concrete results anticipated to occur after a project or activity is delivered. Examples of outputs include the number of flyers or materials distributed, the number of referrals made or workshops offered, or the number of participants who attend a particular service or activity.

Resource assessment

A resource assessment is a way to collect and analyze information about the resources within a particular community or group. Resources can include people or things that can support the community being assessed (e.g., financial resources, the skills and abilities of community members, community space, community programs or activities).

References

PLAN:NET Ltd. (2003, September). Splash and ripple: Planning and managing for results. Retrieved March 18, 2004, from

http://www.ucgf.ca/English/Downloads/RBMSept2003.pdf

Suggested Resources

Websites

Canadian Outcomes Research Institute

http://hmrp.net/canadianoutcomesinstitute/

This website offers general outcome measurement resources and a variety of resources related to logic models.

Innovation Network Online

http://www.innonet.org/

There is no charge to register on this network. It provides general guides to evaluation and an array of logic model resources. Innovation Network Online also provides an interactive Logic Model Builder that assists the user in developing a logic model.

University of Wisconsin

Program Development and Evaluation

http://www.uwex.edu/ces/pdande/evaluation/evallogicmodel.html

This website provides resources, worksheets, and examples of program logic models.

W.K. Kellogg Foundation

Evaluation Toolkit

http://www.wkkf.org/Programming/Resources.aspx?CID=281

This website provides resources on developing logic models and general resources for program evaluation.

Manuals and Guides

Innovation Network Online

Logic Model Workbook

http://www.innonetdev.org/

This workbook is available from Innovation Network Online. It provides a step-by-step process for creating a logic model. Items discussed in the workbook include goals, resources, activities, outputs, and outcomes. Additional logic model resources are provided.

Western Centre for Substance Abuse and Prevention

Building a Successful Prevention Program

http://casat.unr.edu/westcapt/bestpractices/eval.htm

This comprehensive guide illustrates program evaluation using a logic model. Topics include planning an evaluation, building a logic model, and conducting an evaluation using a logic model.

W.K. Kellogg Foundation

Logic Model Development Guide

http://www.wkkf.org/Pubs/Tools/Evaluation/Pub3669.pdf

This is a comprehensive guide to building your own logic model and includes examples and worksheets.

Module 2 Worksheets

Worksheet #1 Step 1: Developing a project/evaluation plan

Title of Crime Prevention Project:

Priority Group:

Project Goals/Outcomes:

Worksheet #2 What is wrong with these outcomes?

- Review the sample outcomes provided.

- List problems with the outcomes provided.

- Re-write the outcomes to correct the problems you have identified.

Worksheet #3:

| Inputs (Drop) | Activities (Fall into pond) | Outputs (Splash) | Outcomes (Ripples) | Impacts (Long-term outcomes) (0uter ripple) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term | Intermediate | ||||

Worksheet #4a:

Case study: Teaching young people to deal with abusive relationships

- The problem: Male violence against women in an isolated, rural community

- Partners: Big Brothers, local high school teachers, local schools, a service club, 2 local businesses

- Goals:

- To reduce the incidence of abusive relationships among young people

- To increase the ability of students in Grades 6-9 to recognize the danger signs for violence in intimate relationships

- To increase students' skills to resolve problems before they lead to violence

- Resources: two in-kind staff from Big Brothers; space and equipment donated by local schools; grants from the service club and, six volunteer facilitators

- Work plan:

- Two in-kind staff will work with teachers to develop workshop materials for a 12-week curriculum on healthy relationships for girls in Grades 6-9

- Two in-kind staff will work with teachers to develop a six-week mentoring project for boys in Grades 6-9

- One in-kind staff will train three facilitators to offer the curriculum for girls

- One in-kind staff will train three facilitators to offer the mentoring project

- Three facilitators will deliver the 12-week curriculum to girls

- Three facilitators will deliver the mentoring project to boys

Step 1: Goals and priority group

Goals

- Reduce the incidence of abusive relationships among young people

- Increase the ability of students in Grades 6-9 to recognize the danger signs for violence in intimate relationships

- Increase students' skills to resolve problems before they lead to violence

Priority Group

- Boys in Grades 6 to 9

- Girls in Grades 6 to 9

The goals listed above were set for the project in the planning stage. The next step is to develop a logic model for the project. As you work through the model, you may identify more specific outcomes than the goals identified here.

Logic model check list

- Do the outcomes represent changes, benefits, results, or impacts of the program?

- Do the outcomes include strong verbs and reflect the direction of change? Are each of the long-term outcomes connected to short-term or intermediate outcomes that lead to them?

- Are the short-term/intermediate outcomes within the control of the program and within the usual time frame for evaluation?

- Is it reasonable to expect, based on previous experience or research (an evidence base), that these intermediate outcomes will lead to the long-term outcomes identified?

- Is there at least one activity that specifically addresses each short-term outcome?

- Is it realistic to expect that the outcomes listed could be achieved given the activities proposed? Should additional activities be added? Should the intensity, duration, or nature of the activities be changed? Or, should the outcomes be rethought?

- Are all of the program activities necessary? For example, are there any activities that do not lead to any outcomes? Are there some outcomes with too many activities linked to them?

Worksheet #4b: Case study: Youth development project for at-risk aboriginal youth

- The problem: Aboriginal youth in an urban community feel disconnected from their culture and their school settings and are at risk of involvement in negative peer activities.

- Partners: Native Friendship Centre, YMCA, summer camp, elders

- Goals:

- To foster honour and respect of traditional culture among inner-city aboriginal youth

- To increase a sense of belonging to a larger aboriginal community

- To encourage the development of healthy ways to express feelings of anger and alienation

- To reduce gang involvement of inner-city aboriginal youth

- Resources: four summer staff at the Native Friendship Centre funded by the NCPC, in-kind contribution of a supervisor from the Friendship Centre, community space at the local YMCA, eight-week time slot at a summer camp, support of two native elders, use of two school buses, four parent volunteers, $7500 in grant money to cover program supplies and use of school bus

- Work plan:

- Two senior summer staff hired for 14 weeks will recruit and select youth, develop and lead program activities for the two-part summer program. The program will involve two program groups each participating in four weeks of urban activities and four weeks at the summer camp at opposing times.

- Two junior staff hired for 11 weeks will assist senior staff in preparation and follow-up activities and in leading summer program.

- Urban activities will include activities to teach youth about aboriginal culture and to explore creative arts and theatre, basketball and other sports activities at the YMCA, discussion groups involving elders, and joint planning by youth to culminate in a community project such as a mural painting, a theatrical event, or a youth-led nature walk for community members.

- Camp activities will be similar to those offered in the city, but with increased focus on traditional culture and life skills, discussion groups, and outdoor sports activities.

- One senior and one junior staff will lead 12 to 15 at-risk youth in the four-week urban program with the assistance of an elder and two parent volunteers. The remaining staff and volunteers will lead a similar group in the four-week summer camp. Both groups will switch programs at the four-week point.

Step 1: Goals and priority group

Goals

- To foster honour and respect of traditional culture among inner-city aboriginal youth

- To increase a sense of belonging to a larger aboriginal community

- To encourage the development of healthy ways to express feelings of anger and alienation

- To reduce gang involvement of inner-city aboriginal youth

Priority Group

- At-risk aboriginal youth from 14-17 years old living in the inner city

The goals listed above were set for the project in the planning stage. The next step is to develop a logic model for the project. As you work through the model, you may identify more specific outcomes than the goals identified here.

Logic model check list

- Do the outcomes represent changes, benefits, results, or impacts of the program?

- Do the outcomes include strong verbs and reflect the direction of change?

- Are each of the long-term outcomes connected to short-term or intermediate outcomes that lead to them?

- Are the short-term/intermediate outcomes within the control of the program and within the usual time frame for evaluation?

- Is it reasonable to expect, based on previous experience or research (an evidence base), that these intermediate outcomes will lead to the long-term outcomes identified?

- Is there at least one activity that specifically addresses each short-term outcome?

- Is it realistic to expect that the outcomes listed could be achieved given the activities proposed? Should additional activities be added? Should the intensity, duration, or nature of the activities be changed? Or, should the outcomes be rethought?

- Are all of the program activities necessary? For example, are there any activities that do not lead to any outcomes? Are there some outcomes with too many activities linked to them?

Worksheet #4c: Case study: Network and coalition building

- The problem: Lack of infrastructure and focused effort to deal with the root causes of crime in a medium-sized community.

- Partners: School board, 4 community centers, 3 local churches, citizens, youth centre, police, employment help centre, mall management

- Goals:

- Increase the development of broad community-based partnerships that can deal with local crime prevention issues

- Increased community/NGO awareness of root causes of crime

- Enhanced community/NGO understanding of and support for what is required to respond effectively to the root causes of crime

- Improved coordination of community crime-prevention efforts

- Resources: half-time crime prevention coordinator, representatives from each of the partner organizations, 10 interested community members, $1000 donated by the mall management, in-kind pace and equipment at community centre

- Work plan:

- The key partners will form a steering committee.

- Steering committee members and the half-time coordinator will recruit additional members with leadership skills.

- Three subcommittees will be formed: a public awareness subcommittee, a professional development subcommittee, and a fundraising subcommittee.

- The steering committee will organize a crime-prevention planning day involving existing community committees and networks with the intent of identifying promising crime-prevention programs to be implemented in the community.

- The public awareness committee will plan and implement one major community awareness campaign in the first year

- The professional development committee will develop and implement professional training opportunities for member organizations on responses to the root causes of crime.

- The fundraising committee will approach local foundations and prepare funding proposals for program activities identified at the crime-prevention planning day.

Step 1: Goals and priority group

Goals

- Increase the development of broad communitybased partnerships that can deal with local crime prevention issues

- Increased community/NGO awareness of root causes of crime

- Enhanced community/NGO understanding of and support for what is required to respond effectively to the root causes of crime

- Improved networking/partnerships among members

Priority Group

- Community at large

- NGOs/churches/businesses

The goals listed above were set for the project in the planning stage. The next step is to develop a logic model for the project.

As you work through the model, you may identify more specific outcomes than the goals identified here.

Logic model check list

- Do the outcomes represent changes, benefits, results, or impacts of the program?

- Do the outcomes include strong verbs and reflect the direction of change?

- Are each of the long-term outcomes connected to

short-term or intermediate outcomes that lead to

them? - Are the short-term/intermediate outcomes within the

control of the program and within the usual time

frame for evaluation? - Is it reasonable to expect, based on previous

experience or research (an evidence base), that these

intermediate outcomes will lead to the long-term

outcomes identified? - Is there at least one activity that specifically

addresses each short-term outcome? - Is it realistic to expect that the outcomes listed could

be achieved given the activities proposed? Should

additional activities be added? Should the intensity,

duration, or nature of the activities be changed? Or,

should the outcomes be rethought? - Are all of the program activities necessary? For

example, are there any activities that do not lead to

any outcomes? Are there some outcomes with too

many activities linked to them?

Module 3: Developing an evaluation plan

Learning objectives

- Ability to develop an evaluation plan, including:

- Identifying evaluation questions

- Developing indicators

- Choosing methods for data collection

- Sampling strategies

- Basic analysis

- Reporting results

What have we got so far?

- We know the project's goals and the priority group it is trying to reach.

- We identified the relationships between the project goals and inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes.

- We understand the assumptions about these relationships.

As you will remember from Module 2, the relationships between project goals and inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes are outlined in the logic model by drawing lines to show how they relate to each other. The assumptions behind these relationships are not portrayed in the model, but it is a good idea to identify these assumptions in the evaluation plan. For each outcome identified, a rationale should be provided to explain why the activity is likely to lead to the particular outcome.

Evaluations of projects funded under the Research and Knowledge Development Fund prepare a theory of change that tests the assumptions made in the logic model against what is known from existing literature.

If you are interested in learning more about how to write up the assumptions behind your logic model or to check the logic of your program, check out the web site:

http://www.theoryofchange.org/html/example.html

What's next?

- Define the purpose of your evaluation and the questions you want it to answer

- Define indicators that will show your project is achieving its goals/outcomes

- Identify sources of information for these indicators

- Determine how you will gather the information

What should an evaluation plan include?

We completed the first two steps (shown in black) in Module 2. In this Module, we will review the remaining steps in developing an evaluation plan.

Identifying evaluation questions

- Determine the goal of the evaluation (not of the project) – This will give you an idea of the questions you will want the evaluation to answer. Seek various perspectives in developing the evaluation questions. For example, find out what the funder, staff, participants, partners, and others want to know.

- Here are some ideas:

- Was the project implemented as planned?

- Did the priority group access the project?

- Did the project achieve its purpose (anticipated outcomes)?

- Were there unanticipated outcomes of the project (positive or negative)?

Identifying indicators

What is an "indicator"?

- A variable (or information) that measures one aspect of a program or project.

- It indicates whether a project has met a particular goal.

- There should be at least one indicator for each significant element of the project (i.e., at least one for each outcome identified in the logic model).

There are two kinds of indicators:

- A process indicator provides evidence that a project activity has taken place as planned.

- An outcome indicator provides evidence that a project activity has caused a change or difference in a behaviour, attitude, community, etc.

So, an indicator must be something we expect to change or vary from the time the project begins (known as the baseline) until a later point when the project activities have taken place and are likely to have had an impact.

Indicators can focus on inputs, outputs, or outcomes, but they should be narrowly defined in a way that precisely captures what you're trying to measure. Indicators are probably the trickiest part of designing an evaluation. They should:

- provide accurate and reliable evidence,

- be easy to gather, and

- provide useful information for making management decisions.

How to choose good indicators

- Validity – Does it measure the outcome?

- Reliability – Does it give a consistent measurement of the outcome over time (i.e., the results do not vary as a result of small changes in the respondent's mood or circumstances particular to a certain day)?

- Timeliness – Does it provide information at appropriate times in terms of project goals and activities?

- Ethics – Can the information be gathered without invading privacy or breaking ethics standards for social research?

- Usefulness – Will it provide useful information for project managers?

- Comparability – Can we compare the results across population groups or approaches?

Think back to the splash and ripple metaphor (PLAN:NET Ltd., 2003) we used in Module 2. If we wanted to measure what impact that drop in the pond had, what would be a good indicator? (Hint: the ripples are the outcomes).

Let's say we decided an indicator of the drop's impact would be the circumference of the outer ripple:

- Validity – Does measuring the circumference of the outer ripple tell us how big the final outcome was?

- Reliability – Would measuring the circumference of the outer ripples for 20 different drops give us an accurate assessment of the final outcome? Or could it change from one measurement to another?

- Note that if it is windy, the ripples might be hard to assess. As we said when we used this metaphor in the previous module, we have less control as the ripples spread, just as projects have less control over longer-term outcomes.

- Timeliness – How might the time when the indicator was measured affect the result?

- Note that if we measure the outer ripple too soon, we might be looking at an inner ripple – a short-term or intermediate outcome – rather than the outer ripple. If we measure too late, the ripple may have faded away. While we generally hope that project outcomes will last and not fade, we don't often know this for sure. Sometimes evaluations include a measurement approximately one year after a program or activity to see if changes found immediately afterward continued to last.

- Ethics – This is not likely an issue with the drop, unless it's in someone's bathtub! But if we're dealing with human beings, we want to respect their privacy and ethical standards.

- Usefulness – What will measuring the circumference of the outer ripple tell us? Will it tell us how big the drop was or how high the palm tree from which it dropped was?

- If we don't know the height of the tree (i.e., a bit about the process of the "intervention"), the information about the size of the outer ripple (or outcome) won't be very useful.

- Comparability – Will the circumference of ripples be comparable across smaller vs. larger ponds? Will it be comparable if the drop falls from a tap rather than a tree?

- These questions have parallels in the real world of project evaluation. The difference between small and large ponds, for example, might be a bit like the difference between projects in urban and rural communities. The difference between a drop falling from a tap and that falling from a tree can be likened to the difference between a project delivered by trained staff versus one delivered by untrained staff.

Some additional considerations when choosing indicators

- Availability – Sometimes the information that would be the best indicator of change is not available. For example, a project aimed at preventing abusive relationships among high school students might wish to obtain information about police reports related to date rape or relationship violence among students in the high schools involved in the project. However, police report information may not be broken down by school district.

- Resources – It would be ideal to do a long-term follow-up of participants in the project described in the example above to determine their involvement in abusive relationships over time. But this may not be feasible due to the large cost involved in such a survey. Resources are a key concern for projects with limited budgets.

- Program needs – Some information may not be available at the time it is required for an evaluation. For example, information about financial inputs may only be available for the project's fiscal year rather than for the time period needed for the evaluation.

- Funder requirements – Some funding bodies require information to be collected in a certain way. If the same information is required for the evaluation, the evaluation plan may need to be adapted to accommodate the project's other reporting requirements.

A good reference tool to help you select indicators can be found in Splash and Ripple: Planning and Managing for Results (PLAN:NET Ltd., 2003).

Identifying information sources

Once you have identified your indicators, you will need to think about who will provide the information you need. It's best to use a number of sources of information.

Researchers often talk about the importance of triangulation. This refers to bringing together information from more than one source. For example, you might analyze results from a pre-post survey, a focus group, and a review of project files. You can then compare the results of each of these separate information sources to confirm whether they are saying similar things. If more than one source reports similar information, you can feel more confident in the validity of the results you report.

The following page provides a list of some typical sources of information and suggested ways to gather information from them:

- Participants – intake form, interviews, focus groups, observation

- Public – surveys, questionnaires, community-level statistics

- Other agencies – focus groups, key informant interviews, surveys

- Project staff – focus groups, key informant interviews, project records/notes

- Media – review of media reports

Choosing data collection methods

How can you get the information?

- Project records/document review

- Interviews/focus groups

- Surveys/questionnaires

- Participant observation

- Population level data/statistics

When deciding what data to collect, how much to collect, and from where, avoid stretching your capacity to collect information. Develop priorities and start with information you can obtain within your organization, such as information on your project's activities and procedures. You can always amend your evaluation plan if you find something surprising that warrants further research.

Although their resources are limited, even projects funded under the Crime Prevention Action Fund should try to find some ways to measure the impact of their projects – how did it make a difference? – and not just the process. At the proposal development stage, groups applying for CPAF funding should think about ways to wrap the evaluation component into their project activities. Focus groups, for example, can sometimes serve two purposes: helping to further community development while at the same time, gaining perspectives on what has worked or what has not worked to date.

In all cases, it's important to ensure informed consent is provided for any information collected. If information collection will include photographs or videos of participants, always obtain participants' permission to use the photos/videos in whatever way is anticipated. When collecting information from or taking pictures of children and youth, first obtain permission from their parents.

Who should get the information?

Decisions about who should collect evaluation information will depend on a number of factors: convenience, the need for objectivity, issues related to the quality of the information collected, and the protection of confidentiality. Sometimes it will be most practical and convenient to have project staff gather information from participants. For example, when staff are already gathering intake information to better understand participant needs when entering a project, it makes sense to adapt the intake interview to include questions for evaluation purposes. In other situations, it is best to have a third party collect the information in order to reduce bias. In still other situations, participants may self-complete questionnaires. When self-completion is considered as an option, potential threats to the quality of data, such as literacy or comprehension of English or French as a second language, should be taken into account.

Closely tied to consideration of who will collect the information is the question of confidentiality. Think about how you will protect the confidentiality, and in some cases the anonymity, of those who provide the information.

When?

Some options include:

- Continuously

- After each event/activity

- At regular intervals

- Before and after programs

When collecting outcome information, at a minimum, you should try to gather information:

- before the project/activity begins (or soon after it begins) and

- after it is complete.

Information collected before a project or activity begins is known as baseline information. It shows what the situation was like in the community or for individual participants before the project or activity began or before individual participants entered the project or activity.

In addition to collecting information after the project is over (or after participants complete a series of project activities), it is a good idea to collect outcome information at another point six months to one year after the intervention. This will allow you to see if any of the changes found immediately after the intervention last over time. This longer-term follow-up may not be possible for small CPAF projects with budget or time limitations.

Factors to consider

Appropriatenes

- Ensure the way you collect information is appropriate to the kind of information you hope to obtain. For example, if you want an in-depth picture of a particular topic or issue, qualitative information might be more useful.

- If your project involves people from various ethnic or religious backgrounds, ensure the data collection tools you intend to use are culturally appropriate. Measures of self-esteem, for example, are often based on a western concept of what represents good self-esteem.

- Match the sophistication of the language used in the instrument to the language skills of the respondents. If respondents have low literacy levels, administer tools orally.