Adapting to Rising Flood Risk

An Analysis of Insurance Solutions for Canada

A Report by Canada's Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation (August 2022)

Table of contents

- Glossary of General Terms

- Glossary of Insurance Terms

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Flood Risk Management in Canada

- 3. Flood Hazard and Damages in Canada

- 4. Equity and Social Vulnerability Analysis

- 5. Building Policy Options for Canada

- 6. Results of Model Analysis.

- 7. Discussion

- 8. Key Findings

- 9. Conclusion and Way Forward

- 10. Annexes

Acknowledgements

This report would not have been possible without the partnership and commitment of all members of the Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation. These dedicated individuals representing provinces and territories, the federal government, and the private sector, worked tirelessly under tight timelines to collaborate on the various elements that culminated in this complex body of work.

The Task Force would also like to thank the many individuals and organizations who contributed extensively to this report. Researchers Dr. Jason Thistlethwaite and Dr. Daniel Henstra from the University of Waterloo, and chief actuaries Dr. Mathieu Boudreault from University of Quebec in Montreal and Dr. Michael Bourdeau-Brien from Laval University all provided their time and significant expertise to advance this work. The Task Force also gratefully acknowledges the input into the work from Indigenous communities and individuals whose perspectives on these topics help to shape the findings, and thanks Kuwingu-neeweul Engagement Services for their assistance with this engagement. Partners for Action was also instrumental in helping the Task Force to understand key considerations for relocation. The Task Force would like to thank Dr. Daylian Cain, Senior Lecturer at the Yale School of Management, for his expertise in identifying insights from the field of behavioural economics.

Finally, the Insurance Bureau of Canada has been an important partner in this endeavor from the very early stages of planning, helping to coordinate the participation of the private sector in the work of the Task Force, and along with the many industry partners, providing thoughtful and constructive feedback on each piece of analysis.

Introductory Letter from the Task Force Principals Committee

June 10, 2022

Rob Stewart

Deputy Minister of Public Safety Canada

269 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa ON K1A 0P8

Romy Bowers

President and Chief Executive Officer

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

700 Montreal Road

Ottawa ON K1A 0P7

Dear Rob Stewart and Romy Bowers,

On behalf of the Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation (the Task Force), we are pleased to present to you the culmination of our work in the enclosed report: Adapting to Rising Flood Risk: An Analysis of Insurance Solutions for Canada.

As you are both aware, Canada is flooding more often, more severely, and with growing social, housing, environmental, and economic impacts. Flood-related disaster costs are at an all-time high and projected to keep rising, exacerbated by climate change and continued development in high risk areas. It is a complex challenge that must be met with multiple interconnected solutions and requires collaboration across whole-of-society partners.

In his December 2021 mandate letter to the Minister of Emergency Preparedness, the Prime Minister of Canada re-affirmed the federal commitment to advance work on one such solution: to bring affordable flood insurance to homes in high risk areas that cannot currently access this kind of protection. Over the past eighteen months, the Task Force, under our guidance as the Principals committee, has taken on this complex work collaborating with federal, provincial and territorial governments, the insurance industry, Indigenous representatives, municipalities, academics, consultants, researchers, and actuarial experts. We are particularly grateful to the tireless efforts of provincial/territorial, federal and industry Task Force members (full membership list in Annex A of the report) who gave their time, energy, and expertise to this work.

This Report presents the facts and the evidence-based analysis of diverse academics, actuaries, researchers and Task Force members. The Task Force brought a variety of skillsets to this work, including a range of technical, policy, and operational backgrounds, and while individual members did not all have the expertise to input into each area equally, every effort has been made to accommodate and include all perspectives. The Report is not intended to represent universal consensus among all organizations or professionals engaged in the process, but to provide the foundational information gathered by the Task Force to advance a national flood insurance solution in Canada.

While important progress has been made in this report, continuing to advance this work will require coordination and commitment from each stakeholder to exercise their jurisdictional role and develop a way forward for implementation. Doing so will help to better protect Canadians, and ensure that flood risk is at the forefront for housing, communities, industry and governments as we strive for a more resilient future.

Yours sincerely,

Principals Committee

Flood Insurance and Relocation Task Force

Trevor Bhupsingh

Assistant Deputy Minister

Emergency Management Programs Branch

Public Safety Canada

Amy Graham

Senior Market Underwriter, VP Americas

Swiss Reinsurance Company

Dave Peterson

Assistant Deputy Minister

Community Disaster Recovery

Emergency Management BC

Steven Mennill

Chief Climate Officer

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

Jordan Brennan

Vice President, Policy Development

Insurance Bureau of Canada

Helen Collins

Director (A)

Municipal Programs and Analytics Branch

Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing

Government of Ontario

Glossary of General Terms

- All-hazards

- An emergency management approach that seeks to comprehensively address vulnerabilities exposed by both natural and human-induced hazards and disasters. This approach increases efficiency by recognizing and integrating common emergency management elements across all hazard types, and then supplementing these common elements with hazard specific sub-components to fill gaps only as required. By assessing the risks associated with all hazards in an integrated way, efforts may be broadly effective in reducing the vulnerability of people, property, the environment and the economy.

- Canadian

- This term is used informally throughout the report to signify any person residing in Canada.

- Core Housing

- Households which occupy housing that falls below any of the dwelling adequacy, suitability, or affordability standards and which would have to spend 30% or more of their before-tax income to pay for the median rent of alternative local market is considered in core housing need.

- Critical infrastructure

- The processes, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and to the effective functioning of government.

- Decile

- Each of ten equal groups into which a population can be divided according to the distribution of values of a particular variable.

- Disaster

- An event that results when a hazard impacts a community in a way that exceeds or overwhelms the community's ability to cope and may cause serious harm to the safety, health or welfare of people, or damage to property or the environment.

- Disaster risk reduction

- The concept and practice of reducing disaster risks through systematic efforts to analyze and manage the causal factors of disasters.

- Emergency

- A present or imminent event that requires prompt coordination of actions concerning persons or property to protect the health, safety or welfare of people, or to limit damage to property or the environment.

- Emergency management

- The management of emergencies concerning all hazards, including all activities and risk management measures related to prevention and mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery.

- Exposure

- The people, property, systems, or other elements present in hazard zones that are thereby subject to potential losses. Exposure data sets for flooding include location data and detailed property information (e.g., presence of a basement in a residential structure).

- Financial sector policy tools

- Tools at the disposal of federal, provincial, and territorial governments with respect to the regulation of the financial sector. These may include measures that could impact aspects of insurance, including the standardization of insurance policies, rules covering the offer, take-up, or purchase of insurance (including but not limited to insurance and mortgage-related requirements), among others.

- Flooding (Pluvial, Fluvial, Coastal)Footnote 1

-

- Pluvial

- The temporary inundation by water of normally dry land, usually caused by extreme rainfall events and not necessarily near to water bodies. Pluvial flooding is common in urban areas where water temporarily accumulates due to more rainfall entering an area than can be removed by infiltration into the ground and discharge through infrastructure (e.g., storm sewers).

- Fluvial

- The temporary inundation by water of normally dry land adjacent to a river or lake and caused by excessive rain, snowmelt, high lake water levels, waves, storm surges, stream blockages including ice jams, failure of engineering works including dams, or other factors.

- Coastal

- Flooding associated with a defined shoreline along an ocean. This can be due to a combination of high tides, storm surges, waves, rising sea levels and riverine flooding.

- Hazard

- A potentially damaging physical event, phenomenon or human activity that may cause the loss of life or injury, property damage, social and economic disruption or environmental degradation.

- High riskFootnote 2

- Defining areas as high risk for flooding can be done in different ways depending on the end intent. Commonly used methods, including applying the 1/100 year return period (or annual exceedance probability) gives an indication of extent of some kinds of floodwater, but not the damage it may cause. To capture the expected risk, and include wider range of flood types, it is necessary to combine hazard and exposure data into metrics such as the average annual loss (AAL) expected at the property level. For the purpose of this report's social vulnerability work and Canada-wide damage estimations, high risk is noted as the top 10% of risk, by AAL (highest risk is the top 1%). For the costing of some insurance models later in this report, 'high risk' will be defined as homeowners who exceed a defined price threshold for coverage of expected damage: where a flood insurance premium would cost over 0.1% of coverage (e.g., $300 for a $300,000 policy).

- High risk homeowners

- For the costing of some insurance models later in this report, 'high risk homeowners' will be defined as those for whom flood insurance premiums exceed a defined price threshold for coverage of expected damage: where the premium would cost over 0.1% of coverage (e.g., $300 for a $300,000 policy).

- Mitigation

- Actions taken to reduce the impact of disasters in order to protect lives, property and the environment, and to reduce physical risk and economic disruption. Note: Mitigation includes structural mitigative measures (e.g., construction of floodways and dikes) and non-structural mitigative measures (e.g., building codes, land-use planning and insurance incentives). Prevention and mitigation may be considered independently, or one may include the other.

- Preparedness

- Actions taken prior to a disaster to be ready to respond to it and manage its consequences. Note: Preparedness actions include emergency response plans, mutual assistance agreements, resource inventories and training, equipment and exercise programs, as well as public education.

- Prevention

- Actions taken to eliminate the impact of disasters in order to protect lives, property and the environment, and to avoid economic disruption. Note: Prevention and mitigation include structural mitigative measures (e.g., construction of floodways and dikes) and non-structural mitigative measures (e.g., building codes, land-use planning and insurance incentives). Prevention and mitigation may be considered independently, or one may include the other.

- Recovery

- Actions taken to repair or restore conditions to an acceptable level after a disaster. Note: Recovery actions include the return of evacuees, trauma counselling, reconstruction, economic impact studies and financial assistance.

- Residence

- The concepts of residences, addresses, homes, households and dwellings are used interchangeably in this Report and they are understood as being synonymous. Properties currently in scope for this Report include residential structures that are privately owned, regardless of type or purpose, and for which no other form of insurance (commercial, agricultural, tenant, condominium) coverage applies.

- ResilienceFootnote 3 Footnote 4 Footnote 5

- Resilience is the capacity of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management.

- Response

- Actions taken during or immediately before or after a disaster to manage its consequences and minimize suffering and loss. Note: Response actions include emergency public communication, search and rescue, emergency medical assistance, evacuation, etc.

- Risk

- The combination of the likelihood and the consequence of a specified hazard being realized; refers to the vulnerability, proximity or exposure to hazards, which affects the likelihood of adverse impact.

- Risk management

- The use of policies, practices and resources to analyze, assess and control risks of health, safety, the environment and the economy.

- Strategic relocation

- Strategic relocation, also referred to as managed retreat, is the purposeful movement of people, buildings and infrastructure out of areas where there is a high likelihood of incurring severe and/or repetitive damage as a result of a hazard. Strategic relocation contributes to disaster risk reduction by effectively eliminating risk within a given area by removing exposed property and assets at highest risk of repetitive hazard impact.

- Viability

- For this Report, viability refers to feasibility of insurance models within the overall Canadian context, while meeting the Policy Objectives established by the Task Force.

- Vulnerability

- A condition, or set of conditions, determined by physical, social, economic and environmental factors or processes that increases the susceptibility of a community, or property, to the impact of hazards. Note: Vulnerability can change over time and is a measure of how well-prepared and well-equipped a community, or property, is to minimize the impact of or cope with hazards.

Glossary of Insurance Terms

- Additional Living Expenses

- The extra expenses incurred when it is impossible to remain in a dwelling which has been damaged by a flood, fire, or another insured peril.

- Average Annual Loss

- Average Annual Loss, or AAL, is the cost of flood damage, expressed in dollars per year, that is expected to occur each year, averaged over the long term. While AAL provides a useful basis for calculating annual insurance premiums, it is important to note that the average can obscure the fact that losses are often negligible most years, and can be catastrophic when a significant flood event occurs.

- Bundling

- The act of grouping together certain perils within an insurance policy (could include different flood perils or could mean bundling flood perils with other natural hazard perils, depending on the design choices of insurance policies).

- Cap (on insurance premiums)

- An upper limit of premium price that is charged to the consumer by the insurer as a way of keeping prices affordable. Employing caps means that some quantity of risk above the premium cap price is absorbed by another entity, policyholders, or funded externally.

- Coverage

- The insurance afforded by the policy.

- Deductible

- The amount of an insurance claim that the insured is responsible for and the company deducts for payment. Deductible can be a dollar amount, a percentage of each claim or a percentage based on the insured amount.

- Endorsement

- An endorsement, also known as a rider, can be used to add optional coverages. Endorsements are contract language used to add, delete, exclude, or otherwise alter insurance coverage.

- Exclusion

- That which is expressly eliminated from the coverage of an insurance policy.

- Homeowners Insurance

- A type of property insurance that covers a private residence. Such insurance typically provides protection for structures and contents against a range of perils (both natural and technical in nature). It also protects the policyholder from certain liability issues and may provide living expenses in the event of loss of use of the property. Depending on the type of policy purchased ("Broad" or "Basic/Named perils" on the low end, to "Comprehensive" or "All perils" on the premium or deluxe end), homeowners insurance policies in Canada often provide coverage for a range of both weather- and non-weather related perils.

- Mandatory offer

- Either by regulation or by contract requirement, insurers selling a specified product must offer specified coverage to any consumer looking to buy their product.

- Mandatory take-up/purchase

- A requirement for homeowners to purchase insurance, typically by government regulation of various economic activities.

- Overland Flood

- Where water flows overland and seeps into buildings through windows, doors and cracks.

- Overland Flood Insurance

- Insurance coverage to provide protection for direct physical losses associated with the overland flood including sewer back-up due to flood.

- Premium Loading Factor

- The additional costs that must be added to a property's average annual losses to calculate a premium price for an insurance policy. The loading factors for this report include costs such as: insurance operating cost, safety margin (covering insurer's losses when higher than anticipated), premium taxes, and the increased level of benefit to consumers of additional living expenses.

- Reinsurer

- An insurance company that specializes in providing coverage to insurance companies for large and or catastrophic losses. Reinsurance is a risk transfer mechanism between an insurance company, and a reinsurer that accepts the risk.

- Residual risk

- Risk that remains after implementing risk mitigation or risk transfer measures. When considering insurance models, residual risk can be thought of as the amount of financial risk that homeowners are not insured for, either the result of being uninsured or underinsured (insured with insufficient coverage for their risk).

- Sewer Backup

- Loss or damage caused by the discharge, backing up or escape of water from a sewer conduits (sump, interior floor drain, or septic tank).

- Tail risk

- Tail-risk flood events are those with a low probability of occurrence, such as floods exceeding the 1 in 1000-year return period. Tail risks are innately uncommon but can cause significant damage in areas of high exposure. Such events would likely not have been captured using historical, or individual, year loss estimates given the relatively short period of comprehensive historical record-keeping from previous flood events.

Acronyms

- AAL

- Average Annual Loss

- AAIL

- Average Annual Insured Loss

- ADR

- Average Damage Ratio

- AEP

- Annual Exceedance Probability

- AFN

- Assembly of First Nations

- ALE

- Additional Living Expenses

- AMI

- Area Median Income

- CD

- Census Division

- CIRNAC

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- CMHC

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- DB

- Dissemination Block

- DFA

- Disaster Financial Assistance

- DFAA

- Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (federal program)

- EM

- Emergency Management

- EMA

- Emergency Management Act

- FIRP

- Flood Insurance and Relocation Project

- FPT

- Federal / Provincial / Territorial

- FRM

- Flood Risk Management

- FTT

- Federal Task Team

- IBC

- Insurance Bureau of Canada

- IPCC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

- ISC

- Indigenous Services Canada

- ITT

- Industry Task Team

- KES

- Kuwingu-neeweul Engagement Services

- NDMP

- National Disaster Mitigation Program

- PC

- Principals Committee

- PS

- Public Safety Canada

- PT

- Province/Territory, or Provincial/Territorial

- PTT

- Provincial/Territorial Task Team

- SOVI

- Social Vulnerability Index

- TF

- Task Force

Executive Summary

Flooding is the source of Canada's most common and costly disasters. In order for a flooding event (the flood hazard) to cause a disaster, it must impact a community in a way that exceeds the community's ability to cope (the exposure and vulnerability). Recent trends are exacerbating both the flood hazard, as well as increasing Canada's exposure and vulnerability to flooding. Climate change is projected to increase the frequency, severity and variability of all types of flooding (pluvial, fluvial and coastal) in the coming decades. At the same time, Canada's exposure to flooding is growing as a result of increasing housing, infrastructure development, and asset concentration in flood-prone areas. Finally, the complexity of Canadian society with its unique characteristics linked to our history and governance systems, demographics, and our relationship with Indigenous communities can perpetuate vulnerability and inequality in disaster impacts. These trends will continue to coalesce leading to increases in the financial cost of flooding on Canadian society in the years to come.

Until recently, disasters in Canada have typically been managed through reactive measures during the response and immediate aftermath of major events. Based on hard-learned lessons from large-scale disaster events of the past two decades, however, federal, provincial and territorial governments have been shifting towards a more holistic and strategic vision for emergency management. This vision emphasizes proactive risk reduction and long-term building back better in order to increase the resilience of Canadian society to future disasters.

For flooding, a key component of this shift is recognizing the power and effectiveness of risk awareness, mitigation, and other risk reduction tools, such as strategic relocation and the use of natural infrastructure, to help manage the impacts of flooding and better protect Canadians. Equally important, is ensuring that Canadians get access to the financial assistance they need following a disaster in order to recover, persevere and adapt to the future.

Insurance is one tool that can provide more predictable and comprehensive financial coverage to Canadians impacted by flooding. Further, by sending a price signal about the true levels of flood risk, insurance can help encourage whole-of-society risk reduction behaviours. In order to be equitable and effective, however, flood insurance must be readily available and affordable for all Canadians. This needs to be true for those in areas most exposed to flooding and for those Canadians most vulnerable to the negative impacts of flood events. The current market, however, fails to cover Canadians in high risk areas, creating a protection gap that renders flood insurance in its present form ineffective in managing flood risk.

A Task Force to Explore Insurance Solutions

The Government of Canada established the Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation (the "Task Force") in order to advance a sustainable solution to rising flood costs. The Task Force conducted its work collaboratively with partners from the Government of Canada, provincial and territorial governments, the insurance industry, and other stakeholders concerned with Canada's growing flood risk. The work of the Task Force included some targeted engagement with academics, Inuit, Métis and Indigenous people living off-reserve, and other organizations. Indigenous Service Canada along with the Assembly of First Nations also undertook a complementary initiative exploring the needs of First Nations with respect to home flood insurance.

The Task Force's work involved several interconnected and concurrent streams of work. At the onset, six Public Policy Objectives were co-created and endorsed by federal, provincial and territorial (FPT) government representatives to guide the exploration and provide an evaluation framework to later assess the viability of insurance arrangements:

- Provide adequate and predictable financial compensation for residents in high-risk areas.

- Incorporate risk-informed price signals and other levers that promote risk-appropriate land use, mitigation, and improved flood resilience.

- Be affordable to residents of high-risk areas, with specific consideration for marginalized, vulnerable, and/or diverse populations.

- Provide coverage that is widely available for those at high risk across all regions.

- Maximize participation of residents in high-risk areas.

- Provide value for money for governments and taxpayers.

Building on the Public Policy Objectives, the early phases of the project included policy reviews, in-depth academic research, international case study analysis, a data-driven social vulnerability analysis, and engagement with FPT governments, the insurance industry, academics, and Indigenous communities. The Task Force, through Public Safety Canada, also developed the most robust flood hazard and damage analysis ever completed in Canada. Finally, the policy research and flood risk data formed the inputs for the actuarial analysis, the final phase of the project needed to help quantify the costs of the four different insurance models explored by the Task Force.

A Shared Evidence-Basis for Decision-Making

This report is a statement of facts and is the output of the Task Force's efforts. The report seeks to provide a common understanding of the evidence and information required to implement viable arrangements for a national approach to flood insurance, with special considerations for potential strategic relocation of those at most extreme risk.

The completion of this report does not infer perfect unanimity among all Task Force members of all points. Where specific differences on issues of substance were identified by Task Force members, they were provided with the opportunity to draft dissenting opinion position papers in order to flag their views but still enable rapid progress in line with majority views or balance of the evidence, under tight timelines. As such, the report is the product of a dedicated partnership among all Task Force members in exploring solutions for this costly and devastating issue.

The report outlines the evidence basis upon which a potential insurance arrangement and relocation strategies could be built. It seeks to articulate the interplay between the Public Policy Objectives and insurance arrangement features. The insurance models analyzed in this report were designed to showcase the relative strengths and weaknesses of different approaches, but were not intended to indicate the exact costs, parameters, and logistics that would be applied in implementation. The report, by design, does not formally recommend or advocate for one particular model over another. This was done because all of the explored models offer specific trade-offs and compromises among Public Policy Objectives, and the decision about which of these concessions are most appropriate is ultimately the purview of FPT governments. Similarly, policy options and program design for relocation is beyond the scope of this work. This report offers readers straightforward, evidence-based information that provides common ground to support timely decision-making.

Key Findings of the Task Force

The work of the Task Force covered research on understanding Canada's risk landscape, analyzing social vulnerability in areas of high flood risk, examining models for flood insurance, and exploring how relocation can help to reduce risk. Key findings are summarized here:

Current Flood Risk

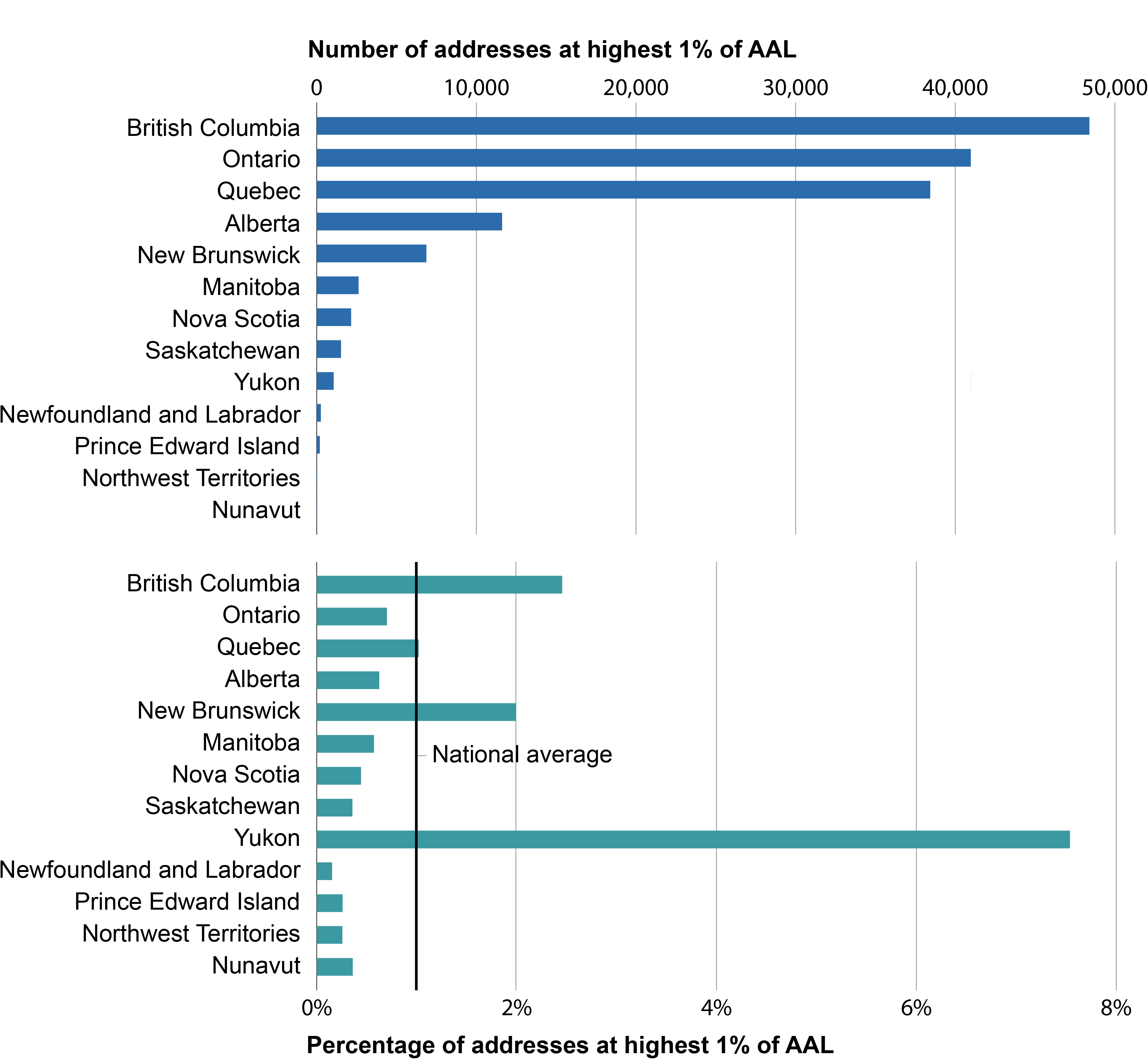

- Total residential flood risk in Canada is estimated at $2.9billion per year

Markedly higher than previous estimates, this amount includes the effects of larger 'tail risk' events and reflects more accurate estimations of a number of residences and predicted damages (based on 2020 data). - The vast majority of risk is concentrated in a small number of the highest risk homes

Of the $2.9 billion, 89.3% is concentrated in the top 10% highest risk homes. 34.1% is concentrated in the top 1% of highest risk homes.

Insurance Considerations

- Some standardization is needed in the market

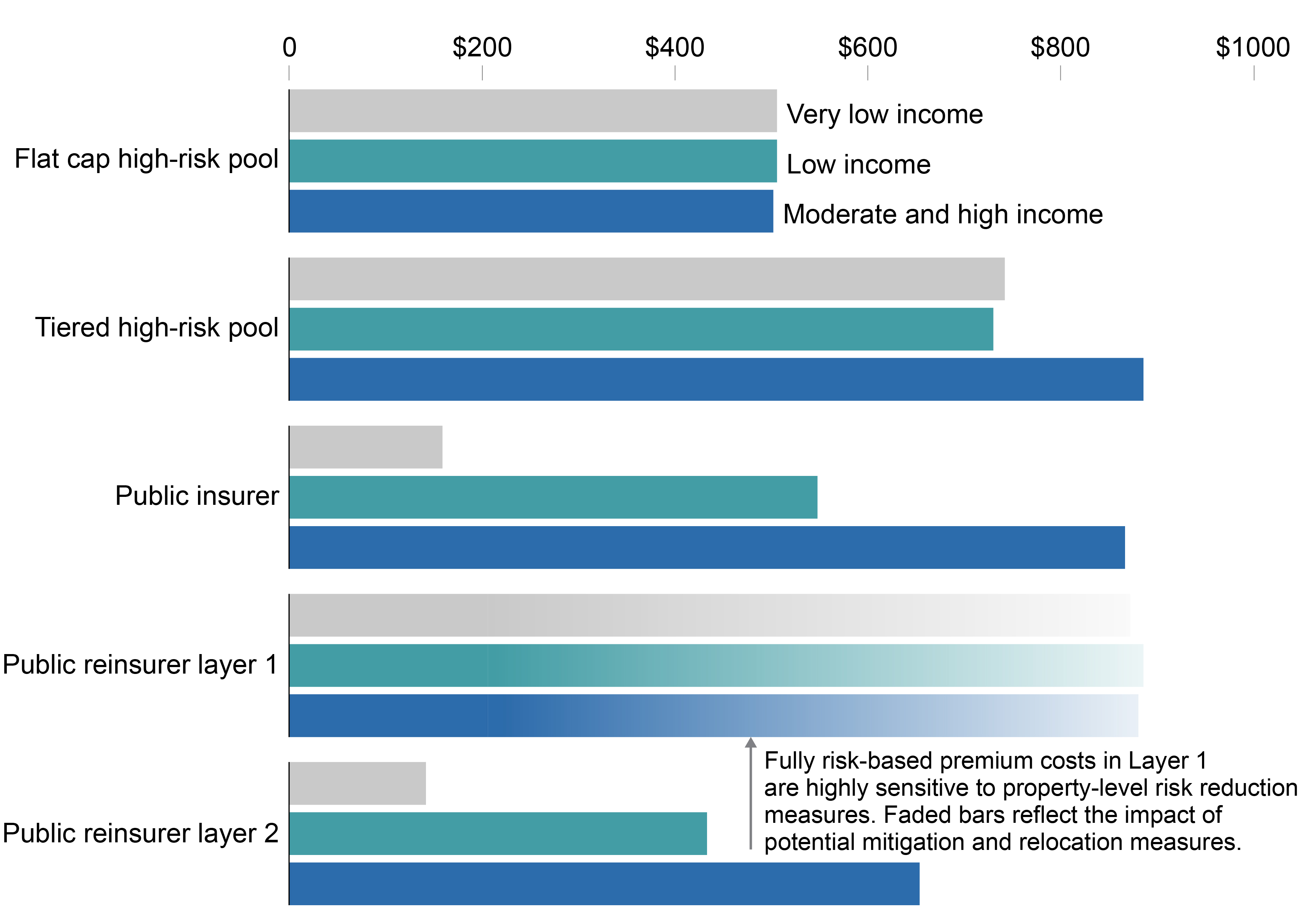

Moving towards clear and standardized language in flood insurance reduces confusion about coverage and allows for a more informed choice for homeowners. Making flood coverage more comprehensive and seamless through bundling of flood insurance products is likely to streamline the claim process, improving both financial and mental health outcomes post-flood. Furthermore, ensuring that Canadians are not left underinsured for their risk is an important consideration for the design of any insurance model. - Participation is key

A carefully designed flood insurance solution can ensure better protection for Canadians, help to share the costs more broadly, and provide incentive for risk reduction. However if such a solution is to replace government financial assistance for residential flood risk, maximizing participation in the insurance arrangement through affordability measures, incentives and/or mandates, is critical to protecting Canadians. Without these interventions, barriers to insurance will remain, leaving more risk on vulnerable Canadians and people living in high-risk areas. - Greater public intervention can more fully close protection gaps, but at a cost

Costs paid by governments are aimed at achieving higher participation rates and increasing affordability. These costs viewed in isolation may seem high, but they must be compared with the alternative scenario: the costs otherwise fall to public DFA programs or on the shoulders of un- or under-insured homeowners. There is no scenario in which these costs disappear without significant investments to remove, or reduce, the risk.

Relocation Considerations

- Relocation can be a powerful risk reduction tool

Relocating the highest risk and repetitive loss properties removes risk rather than transferring or mitigating it, and can be very impactful in improving overall viability and lowering the costs of insurance options. At the same time, the practicality of relocation in areas already experiencing a shortage of available and affordable housing necessitates considerations for in-place mitigation measures. - Relocation must be informed at the community level

Despite the clear risk reduction benefits, relocation is highly complex, and can have major impacts on households and communities. The decision is especially significant for Indigenous communities with strong ties to their ancestral, traditional land. It is important that engagement on how to apply relocation happens early - between jurisdictions and with communities - and offers communities and impacted residents the opportunity to provide input, increasing their sense of agency and trust in the process.

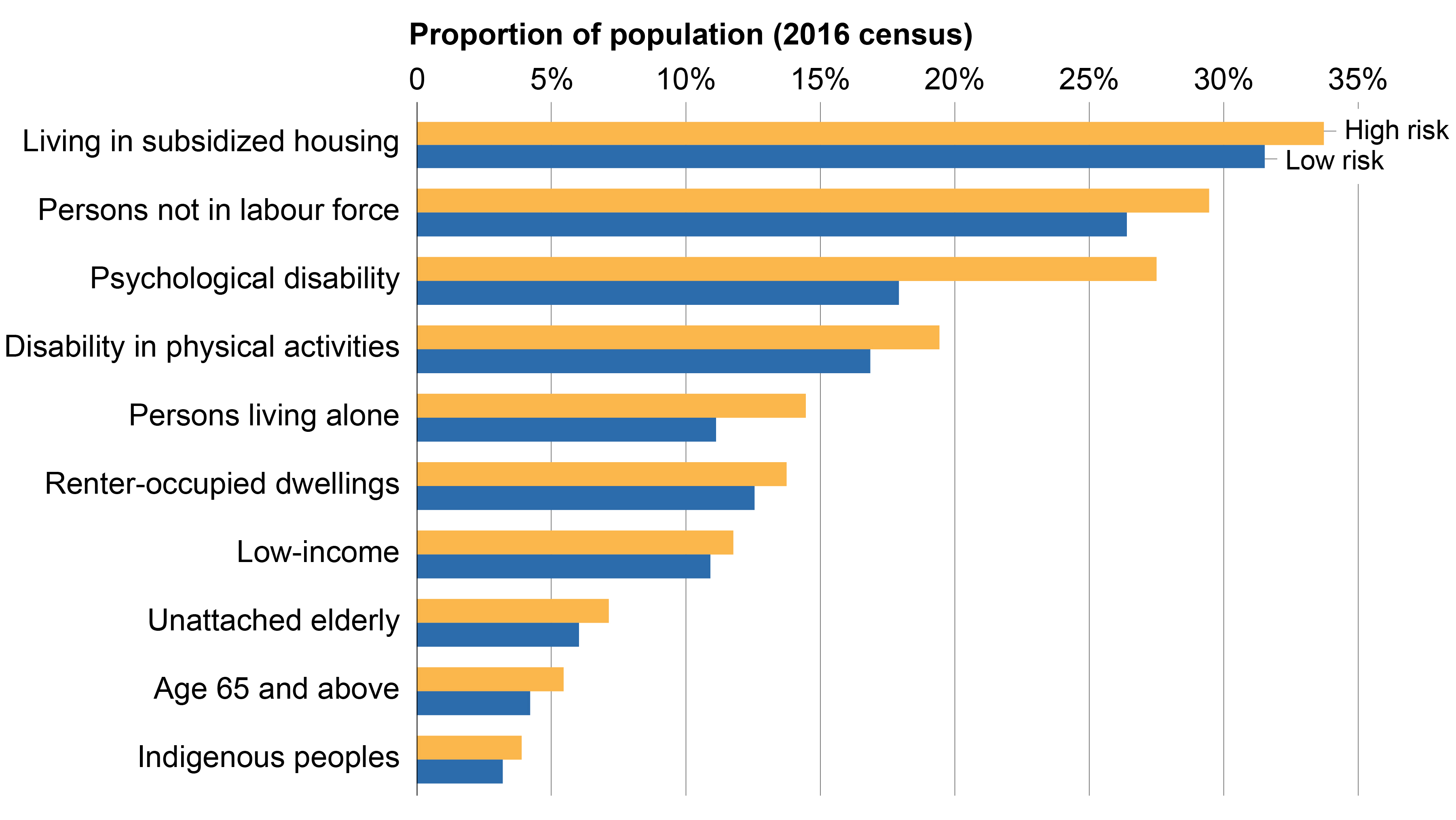

Equity Considerations

- Affordability of flood insurance premiums is key to enabling equitable access

Without supports for socio-economically disadvantaged groups, any program where insurance is optional will likely exacerbate their exclusion and marginalization. For mandatory insurance models, consideration must be given to individuals and communities for whom insurance may not be an appropriate solution (e.g., due to differing home/land ownership arrangements, or for those living in significant poverty). Moreover, targeting affordability measures where needed most can be complex, and considerations of feasibility should factor into model design. - Pathways to accessing insurance are about more than just money

Considerable effort is needed to remove barriers and support access to insurance, which includes promoting greater financial literacy around insurance, building capacity within community organizations that support housing for vulnerable populations, and ensuring a national-level solution can adapt to regional or cultural contextsFootnote 6. The realities for many Indigenous and Northern communities also call for balance and cohesion with related initiatives on housing, poverty, and health. Policies should strive to more broadly reduce the impacts to those most vulnerable to the effects of flooding. - The cultural connections of Indigenous peoples to water and land must be respected

Indigenous knowledge, culture and perspectives on the natural world must be respected, and should be recognized as foundational in informing how all stakeholders can approach flood risk management across Canada. Further engagement with and learning from Indigenous communities, governments, organizations and individuals, including in the form of healing and sharing circles, would help to ensure that FRM initiatives are informed by Indigenous voices.

Living with Water

The foreseeable future suggests that Canadians must learn to live with water. Yet, the country cannot do this at the expense of safety, fiscal responsibility, or equity.

It is clear from this work that flood insurance solutions for high-risk areas can be designed to meet the Public Policy Objectives; however, each model examined contains trade-offs that must be balanced. It is also apparent that given the amount of flood risk in Canada, none of the insurance models can provide affordable insurance and also be financially self-sufficient, at least in the short term. Even over a longer-term (25 year) transition to risk-based pricing, financial sustainability will continue to be challenged by inflation, significant asset concentration in flood-prone areas, and long-term climate change pressures.

Consequently, to live with water, Canada will require more than an insurance solution to address its flood risk landscape. Insurance must be deployed in conjunction with information, investments and incentives at all levels that are designed to reduce flood risk. Such elements include: improved flood mapping and public awareness of flood risk, risk reduction by all stakeholders, improved land-use planning, and climate-resilient built and natural infrastructure. In addition, for an insurance solution to be successful, recovery funding provided to residential properties for flooding though FPT disaster financing programs would need to cease or be restructured to avoid undermining the insurance system. This is an important step towards aligning responsibilities for flood risk.

The findings in this report are meant to provide governments with the foundation to understand the different policy levers and key considerations to be factored into decision-making, and to ensure that any insurance solution strives to effectively meet the defined policy objectives and serve all Canadians impacted by flooding. Particularly, it is important to consider policy options that account for the populations that are disproportionately affected by floods and have lower levels of resiliency to cope with them.

Continuing to advance this work will require coordination and commitment from each stakeholder to exercise their jurisdictional role and develop a way forward for implementation. The collective challenge will be to not let the perfect be the enemy of the good, thereby preventing the implementation of a solution that could nonetheless dramatically improve upon the status quo for Canadians who remain at high risk and who continue to experience tremendous loss from ever-increasing flood events. A new approach to flood insurance will not solve all vulnerability to flooding. However, with a strong stakeholder commitment and decisive action, it could play an important role in empowering Canadians to adapt to flood risk, and building disaster resilience across our nation.

1. Introduction

Globally, natural disasters are increasing in frequency, severity, and economic impact. Drivers of rising disaster impacts include shifting patterns of natural hazards and rising exposure of people, infrastructure, and the environment. In recent years, the gap between insured losses and total economic losses has also widened significantly. In 2020, this "protection gap" widened to a record $231 billion worldwide, with around 75% of potential global losses from natural disasters remaining insured with insufficient coverageFootnote 7. The consequences of this are already being experienced across Canada, where disaster costs have risen dramatically in recent years. Before 1995, only three disasters in Canadian history exceeded $500 million (2014 dollars), but from 2013 to 2017, Canada had disaster losses totaling $16.4 billion. Prior to 2009, insured losses from catastrophic severe weather averaged $400 million per year; since then, the annual average has reached $1.4 billionFootnote 8.

The trajectory of disaster trends poses significant risks to the health and well-being of Canadians, the economy, and the natural environment. Governments and other stakeholders must continue to work together to address the growing impacts of disasters. In 2019, the federal, provincial, and territorial (FPT) governments approved the Emergency Management Strategy for Canada: Toward a Resilient 2030 (EM Strategy), which provides a long-term, strategic vision for emergency management in Canada that is aligned with the United Nations Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk ReductionFootnote 9.

The Emergency Management Strategy seeks to guide federal, provincial, and territorial governments and their respective EM partners (including but not limited to: Indigenous peoples, municipalities, communities, volunteer and non-governmental organizations, the private sector, critical infrastructure owners and operators, academia, and volunteers) to build resilience through five priority areas for action:

- Enhance whole-of-society collaboration and governance to strengthen resilience;

- Improve understanding of disaster risks in all sectors of society;

- Increase focus on whole-of-society disaster prevention and mitigation activities;

- Enhance disaster response capacity and coordination and foster the development of new capabilities; and

- Strengthen recovery efforts by building back better to minimize the impacts of future disasters.

Priority 3 includes as a priority outcome that "FPT governments assist in the development of options for sharing the financial risk of disasters", which could include "engag[ing] the private sector to develop an affordable private flood insurance model for the entire population, including clear incentives for mitigation of flood risks".

In Canada, recent efforts to reduce disaster risk have focused in large part on flooding, given that it is the country's most common and costly natural disaster. Flooding has caused approximately $1.5 billion in damage to households, property and infrastructure in Canada annually in recent years (approximately $700 million in insured losses and $800 million in uninsured losses), with residential property owners bearing approximately 75% of uninsured losses each yearFootnote 10 Footnote 11. Several million homes in Canada are vulnerable to flooding, and many cannot access adequate insurance to protect themselves. These households must rely on their own resources or limited post-disaster financial assistance from governments or not-for-profit groups to recover from flooding events, which do not fully compensate for all financial losses.

To address this gap, the Government of Canada stood up the Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation (the Task Force) with the goal of exploring viable solutions for insurance in high risk areas and considerations for potential relocation of homes most at risk of repeat flooding.

This report covers the findings of the Task Force, summarizing the results of two years of in-depth research, analysis, and collaborative development among stakeholders. It provides an evidence-based understanding of flood risk in Canada, lays out the parameters for potential insurance models, and provides an overview of the impact of relocation and risk reduction to help inform decision-making and the way forward. The report, by design, does not formally recommend or advocate for one particular model over another. This was done because all of the explored models offer specific trade-offs and compromises among Public Policy Objectives, and the decision about which of these concessions are most appropriate is ultimately the purview of FPT governments. Similarly, policy options and program design for relocation is beyond the scope of this work. The Task Force aimed to provide readers straightforward, evidence-based information that provides common ground to support timely decision-making.

This report is organized into the following sections:

Section 1 sets the context for flood risk in Canada, describes the multi-stakeholder environment, defines the problem, and provides an overview of the Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation.

Section 2 defines further what FRM looks like in Canada, and provides an overview of risk reduction.

Section 3 details what has been learned about flood hazard, exposure and risk in Canada, which provides the foundation for much of the analysis to follow.

Section 4 provides a focused sociodemographic analysis of vulnerable people and regions in Canada that warrant important consideration in the analysis of insurance and relocation.

Section 5 summarizes the foundational policy research behind the proposed models, including the findings from an international review, and provides the specific public policy objectives that guide the work of the Task Force.

Section 6 presents and describes the four models that were analyzed, outlines the results of the costing exercise, and provides some high level results on strategic relocation.

Section 7 provides a discussion of what the Task Force learned for each public policy objective, and reviews the general strengths and weaknesses of the four models.

Section 8 provides a summary of the key findings of the Task Force.

Section 9 concludes the report with an overview of next steps, and the collaborative way forward.

1.1 Overview of Flood Risk in Canada

The concept of 'risk' is often misunderstood. In the context of disasters, risk is the combination of the likelihood and the consequence of a specified hazard being realized. It refers to the vulnerability, proximity or exposure to hazards, which affects the probability of adverse impactFootnote 12. Flood risk, therefore, combines the hazard (floodwater) with what is exposed to that hazard (e.g., people or assets), and provides information on the subsequent impacts or consequences. For example, projected increases in extreme precipitation due to climate change may increase the flood hazard by increasing the amount of water expected during flood events, and if this additional flood water is in contact with exposed assets, overall flood risk increases. Similarly, by increasing the exposure of people and assets to flooding by developing floodplains, flood risk increases. It is also possible to reduce flood risk by reducing the physical exposure of structures (e.g., relocation) or the vulnerability of populations to flooding (e.g., by building resilient infrastructure). Flood insurance is a financial risk transfer mechanism, whereas strategic relocation is an effective means of eliminating physical flood exposure.

General types of flooding can include fluvial, pluvial, or coastal, but how these different floods manifest, sometimes in combination, can vary widely across regions. The Rocky Mountains, for example, are susceptible to flash flooding (very rapid increases in water levels), whereas flooding in the prairies can sometimes be anticipated days in advance, allowing more time for flood preparation. In other regions, erosion caused by coastal storm surges and rising sea levels are a significant mechanism of flood losses.

1.2 Key Drivers of Canada's Flood Risk

Population growth and urban development

Canada's densification and development in urban areas already exposed to significant flood hazard is a major driver of flood riskFootnote 13. Although flooding can have devastating impacts on small communities, the risk is more concentrated in large urban centres with higher population densities, which are the fastest growing areas in the country and home to more than 70% of Canada's populationFootnote 14. Many Canadian cities are built on or near floodplains, and more than 6.5 million Canadians live along coastlinesFootnote 15. The growing exposure to sources of flood risk contributes to the increasing frequency and economic consequences of flood events.

Within concentrated areas of population comes increased industrial, service, and trade activity and development, which drive up the value of assetsFootnote 16. The rapidly rising cost of flood events is largely a result of growing exposure, through the increasing number of people and assets in at-risk areas, and the increasing value of those assetsFootnote 17. Many of the metropolitan areas that serve as hubs of Canada's economic activities have substantial exposure to flood risks, including Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver, which are also home to over a third of CanadiansFootnote 18. The geographical concentration of assets is compounded by the increasing trend of homes with finished basements. Without sufficient adaptation, risk mitigation, and maintenance of aging infrastructure, development in at-risk areas will continue to drive up the costs of floodingFootnote 19.

Climate change

Canada's climate is warming at twice the global rate and three times faster in the North. Due to Canada's size and geographic diversity, the impacts of warming temperatures are unevenly distributed and vary significantly across and within regions. Some localities have already begun to experience the effects of climate change on flood risk through shifting rainfall patterns, extreme weather events and rising sea levels, but the greatest impacts are still to comeFootnote 20. Global and domestic climate projections predict more extreme temperatures, sea-level rise, and the increasing frequency and intensity of weather events in the coming decadesFootnote 21 Footnote 22.

There are multiple dimensions to climate-driven flood risk, which impact all regions in Canada. Warmer temperatures increase the likelihood and magnitude of extreme precipitation eventsFootnote 23. This contributes to pluvial flood risk, especially in urban areas which have more impermeable surfaces, such as pavement and concrete, and where design standards for existing aging infrastructure may not account for the higher end of extreme precipitation events. Intense rainfall can increase fluvial flood risk too, especially where these events occur during late fall or early spring when the existence of a snow pack and frozen ground means more and faster runoff into streams and rivers.

Rising sea levels along many Canadian coastlines over the coming decades will increase coastal flood risk for both tidal flooding and storm surges. There is also emerging evidence of a slight northward shift of storm tracks over the North Atlantic Ocean and Canada as a wholeFootnote 24, which may increase the risk of hurricanes and other large storm systems.

Extreme heat also contributes to flood risk, although more indirectly: longer periods of higher temperatures increase the likelihood and severity of wildfires and droughts, which destroy vegetation and topsoil and therefore reduce the ability of local ecosystems to absorb water. When these events are followed by periods of rainfall, the ground cannot absorb as much moisture and the runoff increases the risk of flooding. This pattern was seen in the lead up to the 2021 atmospheric river flooding in British Columbia where extreme heat exacerbated wildfires earlier that year made areas more vulnerable to flooding and landslidesFootnote 25.

Because of the deep complexity and interconnectedness of climatic systems, it is difficult to predict the exact rates of these changes and even more difficult to determine individual local or regional impacts. While some uncertainty exists, the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report cautions that as regions reach climatic tipping points, there is high confidence in the increased probability of severe local impacts and unprecedented weatherFootnote 26. The IPCC has also noted that a key risk in North America is increasing weather and climate extremes (including precipitation events), as well as compounding and cascading climate hazards (e.g., future sea level rise combined with storm surge and heavy rainfall will increase compound flood risks)Footnote 27. How Canada experiences the impacts of climate extremes depends not only on the extremes themselves but on interdependent socioeconomic factors that contribute to exposure and vulnerabilityFootnote 28.

1.3 Defining the Problem

Recent trends in the key drivers of Canada's flood risk – climate change, growing population, increasing housing, infrastructure development, and asset concentration in flood-prone areas – are exacerbating both the flood hazard, as well as increasing Canada's exposure and vulnerability to flooding.

Insurance is one way that Canadians can be predictably and comprehensively covered for flood damages. When operating as a mature and effective market, insurance also sends a price signal about the true levels of risk, spreads the financial burden amongst different stakeholders, and can encourage whole-of-society risk reducing behaviours.

In order to be equitable and effective, flood insurance must be readily available and affordable for all Canadians; this especially needs to be true for those in areas most exposed to flooding. The current failure of the market, however, is that coverage is only being provided in low and medium risk areasFootnote 29, creating a protection gap that leaves the vast majority of flood risk in Canada uninsured. High-risk areas account for approximately 90% of Canada's residential flood risk (see Section 3), which leaves most of the costs for flood damages on the shoulders of homeowners, and for catastrophic events, on government disaster financial assistance (DFA) programs. Therefore, in high risk areas, homeowners either get effectively free insurance (subsidized by taxpayers) through DFA when provided, or are forced to manage the financial risk on their own. This market failure is what the Task Force work is meant to address: how to make flood insurance available and affordable for those living in high risk areas.

90% of the financial flood risk for homes in Canada sits with the top 10% of high-risk homes.

High costs of insurance

In high-risk areas, flood insurance is cost-prohibitive for Canadians, if available at all, and especially so for low income households. In some areas, risk-based insurance premiums could reach $10,000-15,000 or more for flood endorsements alone, on top of other home insurance costs. High housing costs across the nation create an added barrier for homeowners to be able to afford residential flood insurance. Cost and availability of insurance can also be further impacted by recent flood events, because of material changes in risk, or due to increased costs of providing insurance/reinsurance, which can lead insurance companies to raise premiums or withdraw coverage.

Low risk awareness

Current flood maps or other sources of risk information are not generally available or easily accessible for homeowners across the country, and flood risk does not need to be disclosed to potential home buyers. Most Canadians in high risk areas are not aware of their flood risk. This creates three problems. First, when and where flood insurance is available, Canadians may not purchase it due to a lack of awareness of their level of flood risk, or they may erroneously assume flood risk is covered by standard home insurance. Second, homeowners who have purchased optional flood coverage may not have sufficient protection for the amount of risk they face. Unfortunately, it is often only after an event that homeowners discover they are underinsured, or uninsured for their losses. Third, low-risk awareness means homeowners are less likely to make investments in property-level protections for flooding, whether or not they have insurance.

94% of Canadians living in high-risk areas remain unaware of their flood risk.

Source: Partners for Action. (2020). Canadian Voices on Flood Risk.

Misaligned Incentives

The existing system of FPT taxpayer-funded DFA programs contributes to a moral hazard on multiple levels. At the homeowner level, DFA does not provide any incentive to reduce risk or to purchase insurance. At the community level, local governments approve land-use decisions that can maintain or create new flood risk, yet they, along with developers, are rewarded with increased property sale prices and tax revenues. Meanwhile, FPT levels of government bear up to 90% of the public costs to recover and rebuild when floods occur. At the regional and national levels, the cost-sharing of post-disaster funding does not incentivize stakeholders at different levels to reduce risk. FRM and risk reduction through a perverse incentive structure: the expectation that governments will provide effectively free post-disaster financial assistance regardless of risky development decisions reduces the incentive for communities and individuals to reduce their risk or to seek financial protection through insuranceFootnote 30 Footnote 31.

1.4 The Task Force on Flood Insurance and Relocation

In early 2018, the then Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness created an Advisory Council on Flooding with the purpose of advancing the national discussion on flood risk management. The Advisory Council formed a public-private sector Working Group on the Financial Management of Flood Risk, co-chaired by Public Safety Canada and the Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC). In May 2018, FPT Ministers Responsible for Emergency Management requested that the Working Group draw upon international best practices to develop conceptual options for managing the financial costs of high-risk residential properties.

From 2018-2019, the Advisory Council made strong strides in exploring ideas for insurance in high-risk areas, including identifying key principles, conducting a thorough literature review and analysis, and outlining and evaluating possible options for application in Canada. Following this foundational exploration, further work was needed to provide governments with a costed version of the Advisory Council's work, and one that better analyzed and incorporated the needs of vulnerable Canadians.

In November 2020, upon direction from the Prime Minister, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness and the Minister of Families, Children and Social Development stood up the Flood Insurance and Relocation Task Force (the "Task Force") whose mandate was to explore solutions for low-cost flood insurance for residents of high-risk areas and consider strategic relocation in areas at the highest risk of recurrent flooding. The Task Force brought together experts from federal departments and agencies, provincial and territorial ministries, and representatives from the insurance industry, including IBC, to undertake this work.

The Task Force also prioritized engagement with Indigenous communities, with focused dialogues with First Nations off-reserve, Inuit, and Métis communities, organizations, and individuals. The results of this engagement is included in Section 4 of this report. In parallel to the work of the Task Force, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) worked in partnership with the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) on a dedicated Steering Committee on First Nations Home Flood Insurance Needs to examine the unique context for on-reserve First Nations. The ISC-AFN work exists in a separate but concurrent track of work, the results of which will help to inform FPT decision-making processes. The Task Force and Steering Committee worked closely together to ensure alignment and coordination on these two streams of engagement.

Membership and Governance

The Task Force was composed of a diverse group of organizations, sectors and interests. Three task teams (Federal, Provincial/Territorial, and Industry) met regularly throughout to collaborate on the design, analysis, and results of the work. A Principals Committee of senior officials from each of the Task Teams provided guidance and stewardship of the Task Force, while Public Safety Canada provided the administrative, logistical, and analytical support through the Task Force Secretariat (Annex A).

Methodology

The Task Force's work involved several interconnected and concurrent work phases over eighteen months. It began with in-depth and wide-ranging policy research that included case study analyses, literature reviews, an evaluation of best practices both abroad and locally, social vulnerability analysis, consultation with academics, engagement with Indigenous communities, and well as collaboration with the insurance industry and FPT governments. At the same time, a data team at Public Safety sought to accurately calculate the extent of expected flood damages across Canada. To date, their work is one of the most robust flood hazard and risk data analyses ever completed for the country. Finally, the combined policy and data outputs became inputs for the actuarial analysis which quantified the costs and parameters of four different insurance models. The specific components of the above phases used to inform this report included:

Setting the Foundation

- FPT consensus of the Public Policy Objectives to frame the project and its outcomes.

- A lexicon of key terms for the work of the Task Force.

Policy Research

- A detailed literature review on international approaches to flood insurance.

- An evaluation of international flood insurance models and their applicability in Canada.

- A dedicated investigation on special considerations for Canada's North.

- An overview of options and international examples for affordability mechanisms.

- An analysis of best practices and case studies for strategic relocation in Canada.

- An analysis of behavioural economics insights into flood insurance and relocation.

- An FPT and Industry selection of the most promising flood insurance models for Canada.

Engagement

- Provinces/ territories to assess common ground and unique differences on flood risk management.

- Indigenous communities living off-reserve to understand their unique challenges and needs.

- The insurance industry to assess how a public-private partnership could make flood insurance available, and to help develop and shape proposed insurance models.

Analysis of Flood Hazard and Risk Data

- Consolidated Canada-wide flood hazard and flood damage estimates, by Public Safety Canada, to generate one of the most comprehensive geo-locatable national residential datasets used to date in Canadian public policy and natural disaster impact assessments.

Actuarial Analysis

- An actuarial analysis of potential flood insurance models that utilized the in-depth research from previous phases to help quantify costs of different stylized insurance arrangements, and examine the impact of relocation and risk reduction for those homes at the highest risk.

Statement of Fact Report

- Consolidating facts and findings into a cohesive report to support decision-makers.

Scope

Properties in scope for this report include residential structures that are privately owned, and for which no other form of insurance, like commercial or agricultural, applies. These include primary, secondary, vacation, multi-unit dwellings, condos, or rental properties to give an accurate picture of the total sum of residential flood risk and costs in Canada. Large multi-unit dwellings such as apartments or condos, are included in the flood hazard modelling. In these cases, however, it is noted that commercial insurance would likely be in place for the structure, and much of the flood risk remaining for homeowners in multi-unit dwellings would be related to contents. Finally, First Nations residences on-reserve are generally not included in this work due to data limitations and because of the parallel effort led by ISC and AFN focused on examining issues related to flood insurance for on-reserve First Nations.

The types of flood hazards in scope for this report include fluvial, pluvial, and coastal flooding. Other water-related hazards such as sewer back-up (when not related to overland flooding), burst pipes, ice damming on roofs, and tsunami risk are not included in the scope of this report.

Finally, the following federal initiatives, though all important factors for supporting flood insurance and relocation options, are outside the scope of this report because they are being advanced independently of, and in parallel with, this report:

- Federal commitment to complete all flood maps in Canada;

- Federal commitment to provide interest free loans to homeowners for climate change mitigation and adaptation improvements to their domicile;

- Promote flood risk awareness in Canada through a public-facing information portal;

- Specific measures to improve flood mitigation in communities at risk of recurrent flooding;

- Examination of flood risk and context-specific insurance options for First Nations on-reserve communities.

2. Flood Risk Management in Canada

Traditional approaches to managing flood risk involved governments building expensive structural controls that aimed to keep people and property separate from sources of floodingFootnote 32. With the rising costs and frequency of flooding, however, there is a global shift underway in learning how to live with water.

Flood risk management (FRM) is an alternative approach to conventional control measures that shares the responsibility for flood risk across a wider array of stakeholders and promotes the use of non-structural mitigation measures to complement and enhance other types of mitigation to reduce the risk and impact of flooding. In Canada, FRM spans all orders of government, industry sectors, communities, non-government organizations and individuals. FRM is by definition informed by risk, and involves an iterative process of acting, monitoring, reviewing and adapting.

Canada is a federation where each order of government has specific areas of jurisdiction, and roles and responsibilities may be exclusive or shared. How these differ, how revenue-based constraints (like taxation of incomes and consumption) may affect them, and how land use is planned and approved, are central to understanding what makes the landscape of FRM in Canada particularly complex.

2.1 Roles and Responsibilities for Flood Risk Management

Federal Government

The federal government's primary role in FRM is to coordinate with and support PTs and local efforts to mitigate, prepare for, respond to and recover from flood emergencies. This role stems principally from the Emergency Management Act (EMA), S.C. 2007, c. 15. Under the EMA, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness is responsible for exercising leadership related to emergency management in Canada by coordinating among government institutions and in cooperation with PTs and other entities. The EMA also provides the Minister with responsibilities for monitoring emergencies, coordinating the Government of Canada's response, and providing resources or financial assistance to PTs under certain conditions. Financial assistance to PTs is largely provided through Public Safety Canada's Disaster Financial Assistance ArrangementsFootnote 33 (DFAA) program, which currently funds a significant share of the costs for flooding in high risk areas. Under the EMA, the Minister is also responsible for exercising leadership at the national level relating to emergency management, which is central to the role of working with all stakeholders to address the rising costs of disasters and the increased risk of catastrophic events faced by Canadians. Other federal ministers also have emergency management responsibilities within the EMA as it pertains to their respective area of responsibility, for which they are accountable to Parliament.

Two other pieces of legislation are relevant to FRM. First, under the Department of Indigenous Services Act, S.C. 2019, c. 29, the Minister of Indigenous Services is responsible for providing emergency management services to, and assisting with disaster recovery for, Indigenous individuals, and Indigenous governing bodies, in partnership with PT governments and third-party service providers such as the Canadian Red Cross. Second, under the Canada Water Act R.S.C. 1985, c. C-11, the Minister of the Environment works with relevant PTs in matters relating to water resources. Joint projects involve the regulation, apportionment, monitoring or surveying of water resources. Under partnerships with PTs, the federal government is responsible for providing critical hydrometric data, information, and knowledge that Canadians and their institutions need to make informed water management decisions to protect and provide stewardship of fresh water in CanadaFootnote 34.

The Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (DFAA)

Established in 1970, the DFAA is a federal cost-sharing program to assist PTs with response and recovery costs for large-scale disasters. The DFAA reimburses PTs for eligible disaster costs related to the provision and restoration of essential services and the repair of damaged infrastructure. PTs are responsible for designing and administering disaster financial assistance (DFA) programs in their jurisdictions to provide direct assistance to individuals, small businesses, not-for-profits, and local governments. Most PT programs generally align with DFAA eligibility criteria to maximize federal reimbursement, however, there is considerable variance across Canada in the coverage provided, and the relative maturity and capacity of DFA programs.

Since the inception of the DFAA, the Government of Canada has paid in excess of $6 billion in post-disaster funding to PTs, and over 62% of that has been paid out in the last 10 years. The recent atmospheric river events in BC are likely to add approximately $5B in future payments, and costs are expected to continue to rise significantly in future years.

Effective FRM also engages a number of other federal departments, including: Transport, Natural Resources, National Defense, Infrastructure, Heritage, Fisheries and Oceans, and Foreign Affairs. Nationally, the Government of Canada monitors and shares information about some of the contributors to flood risk, such as weather forecasts, climate models, and sea levels. Data and technical guidance helps support PTs in developing regional or local flood maps and flood forecasts, and citizens can access generalized information on preparing for floodsFootnote 35. There remains a large gap, however, with respect to publicly available, up to date, and comprehensive flood risk information for Canadians. There is a shared commitment to address this gap through PT and local flood mapping efforts, supported in part by over $60 million in federal funding announced in the 2021 Federal Budget, as well as a federal commitment to develop a public flood risk portal, which together would help to increase risk awareness, transparency, and preparationFootnote 36.

In terms of insurance, some insurers are incorporated under federal legislation, which allows them to carry on the business of insurance throughout Canada, while others may choose to incorporate only in the specific jurisdictions they wish to operate. Regardless of where insurers choose to incorporate, business activities of these companies are generally regulated by the provinces.

Provincial and Territorial Government

PT governments play a central role for FFRM in Canada through their regulations and policies in matter of land use, their jurisdiction and oversight over municipalities, and their roles as regulators on the business activities of the insurance sector, including product design. PT governments have historically taken different approaches to FRM within their jurisdictions, including varying degrees of delegation to municipalities. PTs may establish land use planning standards to mitigate flood risks, and some have undertaken significant infrastructure investments in flood protection (Manitoba's Red River Floodway, and Alberta's recent investment in the Springbank Off-Stream Reservoir near Calgary). Furthermore, PTs may impose requirements in matters of the design, construction, and maintenance parameters for buildings and other infrastructure built in risk area whereby they can choose to adopt, as is, or modify the National Building Code of Canada Footnote 37 Footnote 38. Their authority over land use includes regulating and permitting natural resource development such as mining or logging and the responsibility to develop flood maps for their jurisdictions. Some PTs may also have other governmental entities responsible to enforce and implement construction-related legislation on their behalf. La Régie du bâtiment du Québec, for example, enforces the Building Act, Construction Code and Safety Code, to ensure quality construction and renovation work, and issue or modify related permits.

In addition to legislation that delegates specific authorities to local governments, some PTs have legislation specific to emergency management and the responsibilities of municipalities to prepare for, respond to, and recover from emergencies, including flood events. PTs are responsible for coordinating the response to emergencies within their borders, but some often work closely with neighbouring jurisdictions both in Canada and the United States, and can request federal assistance and resources when required.

When individuals and organizations experience losses due to major flood events, PT governments may provide DFA through a formalized program, or through ad-hoc funding mechanisms to facilitate reconstruction. Some provinces, like Quebec, do not authorize reconstruction in the same location if it is in a high-risk flooding zone and the property meets certain risk-based criteria. In some instances, PTs have opted to purchase and demolish damaged residences to enable homeowners to relocate to a less risk area. Currently, DFA programs often exclude coverage for insurable losses, however, determining what qualifies as insurable can be a complex endeavour given the high costs and limited ability to purchase flood insurance in some areas. At this time, therefore, many PTs recognize the need to maintain some flexibility in their DFA programs and apply discretion when determining if residential flood insurance is reasonably and readily available.

Municipal Government

Under Canada's Emergency Management Framework, municipalities have a role in leading local response and recovery, however, they are also highly dependent on other levels of government for resources and funding when significant events occur. Municipalities are responsible to enforce their by-laws and may be subject to PT legislation in matters of land use or construction. At times, municipalities may be limited in matters of zoning by-laws, development, and permits by PT environment or agricultural oversight bodies, however, municipalities also have the ability to require local standards to be higher than PT minimums. In terms of FRM, municipalities can reduce flood impacts by working with PTs to identify flood risks in their jurisdictions, investing in structural and non-structural mitigation and by implementing economic incentive programs such as subsidies, rebates, or risk-based surchargesFootnote 39. These efforts often require support from and collaboration with multiple levels of government. Local governments are often on the frontlines of FRM in Canada, which they manage through limited fiscal capacity constrained by revenue sources available to them and their dependence on property taxes to fund programs and services. This can put municipal governments into a challenging role. Although they have the responsibility to comply with PT land use planning regulations and policies, they also have a vested interest in maximizing property taxation revenue to fund programs and services for residents, including for disaster response. Without broader cross-jurisdictional support, however, these two competing interests can be at opposite ends of the FRM incentive spectrum, further complicating risk reduction efforts.

Indigenous Communities

For generations, Indigenous communities of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples have turned to traditional knowledge to foster a holistic approach to disaster risk reduction. The ongoing challenges stemming from colonial history that resulted in loss of lands, language, and culture, however, has disproportionally compounded the impact of flooding for Indigenous peoples, and created added challenges for FRM. Although it is understood that all communities have a responsibility to prepare for disasters and contribute to community resiliency, the jurisdictional complexity that northern, urban, and rural Indigenous peoples have to navigate in order to access support creates an added burden. Further, unique geographies, socio-cultural characteristics, sometimes limited access and proximity to resources, and higher flood risk in many northern and remote communities warrant special considerations for FRM for Indigenous peoples.

Emergency and FRM are a shared responsibility, handled through partnerships between Indigenous communities and their governments, federal, PT governments, and non-governmental organizations. Indigenous communities are responsible for developing community emergency management plans that include assessments of hazards, risks, and vulnerabilities faced by the community, and ensuring plans are exercised and maintained.

Federally, Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) works closely with First Nations and partners to bolster emergency preparedness and administer the Emergency Management Assistance Program (EMAP) as the primary source of federal funding to reimburse on-reserve emergency management activities, including flood mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery. In addition, ISC works with First Nations to support structural mitigation projects, such as dikes, sea walls, erosion-control measures, that protect First Nations communities from increased climate-related hazards. Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada (CIRNAC) provides funding to help these communities assess and respond to climate change impacts on community infrastructure and disaster risk reduction through the First Nation Adapt Program. Furthermore, it is important to note that federal government has legal a Duty to Consult when it is contemplating any conduct or action that might adversely impact potential or established Aboriginal or Treaty rightsFootnote 40.

The recurring number of emergencies, the vulnerability of many First Nations communities to emergencies, and extensive recovery time continue to pose problems for Indigenous communities. Moreover, challenges exist in accessing flood insurance, due not only to a lack of availability and affordability, but also because efforts do not always align with Indigenous cultures, land use practices, ownership structures, ways of knowing, and worldviews (see Section 3).

Insurance Industry

Water-related claims are today's primary cause of home insurance losses in Canada and are expected to continue increasingFootnote 41. The primary role of the insurance industry for FRM in Canada is the financial transfer of flood risk from homeowners to insurers through the provision of flood insurance, often added either as part of a bundled peril endorsement or specific to a single peril. Some insurers offer varying degrees of overland flood endorsements (fluvial and pluvial risk), while coastal storm surge coverage remains limited. Most insurers provide endorsements for sewer backup, and while this is outside of scope of this report, there can be complexities in distinguishing sources of and responsibility for costs when sewer backup occurs concurrently with or is caused by overland flooding. The industry also regularly participates in data collection, research and public outreach initiativesFootnote 42. Flood insurance can incentivize policy holders to undertake risk reduction measures to lower their premiums, and with high enough take-ups rates, it can help to shift some of the financial flood risk burden away from FPT government DFA programs. In addition, when the appropriate level of flood insurance is purchased, policies can generally compensate consumers more fully and more quickly than government programs.