ARCHIVED - Quadrennial Search and Rescue Review - Report

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Table of Contents

II. The Challenge of Search and Rescue Operations in Canada

III. Canada’s National Search and Rescue Program – Division of Responsibilities

IV. Canada’s National Search and Rescue Program – The Two Pillars

Air & Maritime Response Assets

Response: Coordination, Compatibility and Interoperability

Data Management & Performance Measurement

Executive Summary

In May 2013, the Minister of National Defence, as Lead Minister for Search and Rescue, announced the initiation of the first Quadrennial SAR Review, to provide a comprehensive perspective of Canada’s National SAR Program (NSP).

This inaugural Quadrennial SAR Review represents an important first step in developing a comprehensive perspective of the National SAR Program. The thoughtful input that was received from SAR stakeholders across the country is a testament to the enduring commitment of this community to improve the safety of Canadians. The dialogue that has been started through this process must continue as we chart the future course of the National SAR Program.

Canada’s National SAR Program rests on the contributions of many different partners from across the country, representing all three levels of government and a cadre of dedicated volunteers. Together, they pursue two main lines of activity: prevention and response.

Prevention can have a profound impact on the frequency and severity of SAR incidents, and is a shared responsibility across the entire NSP partnership.

The responsibility for response is divided by domain (air, maritime, ground):

- The Federal Government is responsible for the aeronautical and maritime elements of SAR response (through the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Coast Guard), and for ground SAR in National Parks and Historic Sites (through Parks Canada);

- The provinces and territories are responsible for SAR response on land (i.e. ground SAR) and inland waters; and,

- Volunteers play an integral role across the air, maritime and ground domains.

The divided responsibilities, varied approaches and complementary capabilities between levels of government and across paid and volunteer organizations result in a fluid and flexible system, able to meet the diverse challenges that arise across the country.

While Canadians can be confident that they have one of the most effective SAR systems in the world, the “no-fail” nature of the SAR mission demands that program stakeholders remain committed to continuous improvement.

In that vein, SAR stakeholders from across the country offered wide-ranging input to this inaugural review process. This input will inform the federal government’s ongoing assessment of federal SAR governance structures to ensure that these mechanisms support the effective and efficient delivery of SAR services to Canadians.

This input also shaped the development of the following recommendations, which will contribute to ongoing efforts to ensure that Canadians continue to enjoy a world-class SAR system:

- Standardized reporting and improved data management across the NSP must continue to be pursued without delay, as it would serve to inform future decision-making, and would set the SAR community on the proper footing for successful reviews in the years to come.

- As a fundamental and invaluable pillar of the National Search and Rescue Program, prevention efforts should be further emphasized and more effectively coordinated across the NSP partnership.

- Given the substantial role played by volunteer organizations in the delivery of SAR excellence in Canada, this cadre of dedicated Canadians must be supported and sustained by the NSP partners.

- To ensure ongoing “seamless” SAR delivery for Canadians, all NSP partners must continue to improve coordination, collaboration and interoperability across the system, including better leveraging of existing mechanisms.

- The National Search and Rescue Secretariat should further leverage the SAR New Initiatives Fund and the annual SARscene conference (a national event involving all NSP partners and volunteers) to support immediate measures, and – more importantly – to advance the national dialogue on these issues with the aim of identifying system-wide, sustainable solutions for the future.

I. Background

Search and Rescue in Canada is a shared responsibility across all levels of government, and is delivered with the support of the private sector and thousands of volunteers. This network of partners is called the National SAR Program (NSP).

In May 2013, the Minister of National Defence, as the Lead Minister for Search and Rescue, announced the initiation of the first Quadrennial SAR Review (QSR). This systematic, standardized review is intended to provide a comprehensive perspective of Canada’s National SAR Program, with a view to enhancing integration and alignment to ensure a seamless system for Canadians.

Under the leadership of the National Search and Rescue Secretariat (NSS), NSP partners and stakeholders from across Canada were engaged in the review, including all federal, provincial, territorial and municipal partners, as well as the private sector and volunteer organizations.

Input from NSP partner organizations was gathered through a survey, and subsequently confirmed through a forum that was held in Ottawa on 15 July 2013. The broader Canadian public, industry stakeholders and other interested organizations were also given the opportunity to engage in the review process by offering their views through written submissions.

II. The Challenge of Search and Rescue Operations in Canada

Canada has one of the world’s largest areas of responsibility for search and rescue, covering 18 million square kilometres of land and water, more than 243,800 kilometres of coastline, three oceans, three million lakes (including the Great Lakes), and the St. Lawrence River system.

The challenges associated with such an enormous area are compounded by the varied and often austere terrain, extreme weather conditions and low population density that characterize many parts of the country, making Canada one of the most difficult environments in which to conduct search and rescue operations.

Against this backdrop, commercial and recreational activity in Canada is high, with some twelve million aircraft movements and over six million recreational boaters out on the water every year, and with Canadians and foreign tourists engaging in popular – and often risky –outdoor sports and recreation activities.

This is the demanding context that drives the national SAR system – a system that is called upon to respond to more than 15,000 calls each year, and which provides assistance to over 25,000 people.

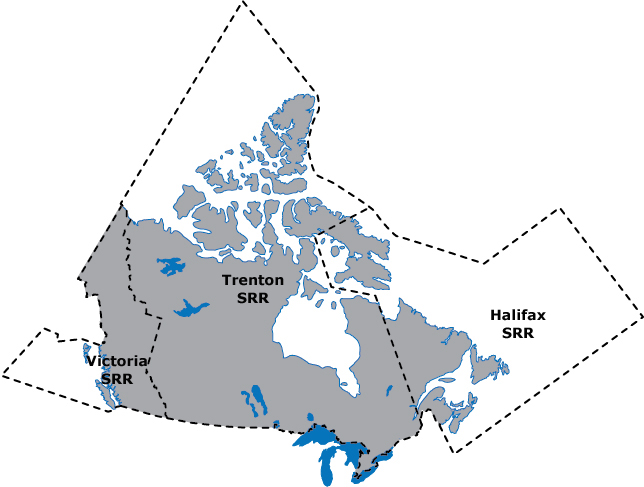

Canadian Search and Rescue Regions

III. Canada's National Search and Rescue Program - Division of Responsibilities

Canada’s National SAR Program rests on the contributions of many different actors from across the country, representing all three levels of government and a cadre of dedicated volunteers. While each partner has specific roles and responsibilities, they work together to achieve a single result: to save lives.

The National SAR Program - Partners

The Federal Level

The Federal Government is responsible for the aeronautical and maritime elements of SAR, and for ground SAR in National Parks and Historic Sites.

The federal approach to aeronautical and maritime SAR is guided by international standards and conventions, including the Convention on International Civil Aviation (1944), the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (1974), the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (1979), the Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime Search and Rescue (1979), the International COSPAS-SARSAT Program Agreement (1988), and the Agreement on Cooperation on Aeronautical and Maritime SAR in the Arctic (2011).

The National Search and Rescue Secretariat, established in 1986, serves as a central coordinator for the National SAR Program, with direct responsibility and accountability to the Minister of National Defence, as the Lead Minister for SAR. The Secretariat focuses on national and international coordination, policy and program support, and helps facilitate cross-jurisdictional efforts in such areas as prevention and interoperability. Of particular note, the Secretariat has responsibility for leading Canada’s engagement in COSPAS-SARSAT, administering the SAR New Initiatives Fund, and organizing the annual SARscene conference.

COSPAS-SARSAT is an international satellite-based system that provides distress alert and location data to help search and rescue authorities assist persons in distress. It was established by Canada, the US, France and Russia, and now involves over 40 countries and two non-state organizations. Since its inception in 1988, COSPAS-SARSAT has been credited with saving over 35,000 lives.

The SAR New Initiatives Fund is a contribution program aimed at enhancing SAR prevention and response in all jurisdictions across the country. Through this fund, the Secretariat distributes $8.1 million annually of project-based funding to partners in the National SAR Program. To date, the Secretariat has distributed more than $200 million in funding to over 880 projects across Canada.

SAR New Initiatives Fund – 2013/14 Project Examples

- Remote Ground to Air SAR Communications (British Columbia) – $151,435

- Avalanche Prediction Improvement (Parks Canada) - $182,807

- Newfoundland and Labrador Standardized Radio Real Time Tracking System(Newfoundland and Labrador Search and Rescue Association) - $955,827

The annual SARscene conference is a national education and networking event for search and rescue professionals from across the country and internationally. Founded on the precept of “working together to save lives,” SARscene is the only such professional development and networking opportunity for the Canadian SAR community.

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) is responsible for aeronautical SAR anywhere within Canada’s designated area of responsibility, and for the effective operation of the coordinated aeronautical and maritime SAR system.

While ground SAR and other humanitarian operations fall outside of the military’s primary SAR responsibilities, they are nevertheless often called upon to assist other federal departments or provincial/territorial governments.

Moreover, the Canadian Rangers may routinely be asked to assist in ground SAR operations, as they can provide SAR specialists with invaluable knowledge and advice on the terrain, weather and conditions in the search area. The Province of Ontario, for example, recently concluded a Memorandum of Understanding with the Canadian Rangers, which sets out the process through which the Rangers’ assistance can be requested.

The Canadian Coast Guard is responsible for maritime SAR in areas of federal responsibility (i.e. in the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence River system and coastal waters). As such, the Canadian Coast Guard detects maritime incidents, works with the Canadian Armed Forces in the coordination and delivery of maritime SAR response within areas of federal responsibility, provides maritime resources to assist with aeronautical SAR operations as necessary, and when and where available, provides SAR resources to assist in humanitarian incidents within provincial/territorial jurisdiction.

Parks Canada, under the Canada National Parks Act, is responsible for visitor safety on all lands within its jurisdiction – i.e. ground and inland water incidents in the 44 National Parks and the more than 120 National Historic Sites across Canada, including in the Arctic.

Transport Canada provides safety education; develops and enforces minimum safety standards in the design, manufacture, and operation of all components in the aeronautical and maritime sector; assesses the impact of accident investigations on safety regulations; and regulates distress beacons.

Environment Canada provides critical information on meteorological conditions, for use by the Canadian public and NSP partner organizations.

Additional Federal Government infrastructure and assets, although not specifically designated for search and rescue purposes, can also be brought to bear in SAR prevention and response, when appropriate.

Provinces & Territories

The provinces and territories are responsible for SAR on land (i.e. ground SAR) and inland waters.

To meet their individually unique circumstances, each province/territory has its own arrangements for coordination and delivery of SAR response. Despite differences in their legislative and regulatory bases for organizing SAR, provincial/territorial approaches to SAR are usually organized under emergency management agencies, and/or are placed under the authority of law enforcement agencies (RCMP, provincial and/or local) to coordinate SAR operations within their jurisdiction.

Provincial/territorial geographical areas of responsibility are generally limited to their provincial or territorial jurisdictions. However, some provinces and territories have limited international cooperation agreements with bordering US states or have additional responsibilities under international Memoranda of Understanding.

In New Brunswick, the Department of Public Safety policing services is responsible for administration and support to ground SAR operations, and co-chairs the New Brunswick Ground Advisory Committee. Provincial SAR policy coordination is done through this Ground SAR Advisory Committee, which also works collaboratively to ensure sufficient ground SAR capability by promoting strong partnerships among emergency service providers, including the ground SAR community, police, government agencies and other stakeholders. Responsibilities and authorities are defined in the New Brunswick Search and Rescue Protocols (2012), created by the Ground SAR Advisory Committee. Prevention activities are managed by SAR volunteers.

Volunteer Organizations

Each and every day, thousands of SAR volunteers throughout the country are on-call to provide life-saving assistance to Canadians in distress. These volunteers are critical to the success of the National SAR Program, playing an integral role across the air, maritime and ground domains, in support of all levels of government.

In British Columbia, ground SAR volunteers must complete approximately 100 hours of training, covering the following:

- SAR in BC

- Initiating a search

- Search progression

- Search termination

- Maps & compasses

- Survival skills

- Search types (sweep, grid, shoreline)

- Communications

- Rope Management

- Tracking

- Helicopter Safety

- Avalanche Orientation

- Evacuation

IV. Canada's National Search and Rescue Program - The Two Pillars

The National SAR Program has two main lines of activity: prevention, and response.

Prevention

The prevention pillar reinforces personal responsibility through education, regulation, investigation and enforcement. These preventive steps can have a profound impact on the frequency and severity of SAR incidents, and can mean the difference between life and death for Canadians.

The prevention pillar permeates the efforts of all NSP partners. For example, at the federal level, the Department of National Defence, through the National Search and Rescue Secretariat, offers information on how to prevent incidents, alert the system and survive pending rescue. These publications and presentations are used extensively by the SAR community for awareness and outreach events. Parks Canada ensures proper signage on trails, and provides up-to-date hazard information to visitors. Environment Canada enables Canadians to make informed decisions on changing weather, water and climate conditions, while Transport Canada sets and enforces important safety standards for aeronautical and marine transportation, including recreational boating.

Amongst the provinces and territories, prevention efforts vary across the country. They range from educating the public regarding safe practices for common outdoor activities, to mitigation measures such as improving the safety and accessibility of parks and recreation sites, to enforcement of laws regarding the responsible operation of vessels or off-road vehicles.

In delivering these prevention programs, the provinces and territories often rely on other partners, including police services and SAR volunteers. For instance, volunteers are heavily involved in the AdventureSmart program, which emphasizes personal responsibility for safety, and educates members of the public on how to alert the search and rescue system when in distress and how to survive until rescued.

AdventureSmart is a national program dedicated to encouraging Canadians and visitors to “get informed and get outdoors,” and is framed around three simple steps: trip planning, training, and taking the essentials.

Indeed, volunteers – by reaching into their local communities to provide information, raise awareness, and enhance preparedness – help prevent SAR incidents in the first place and greatly improve the chances of survival should something go wrong.

Response

Phases of Response

Although every SAR incident is unique, there are generally five phases to a SAR response: incident occurrence, alert, investigation, response, and post-incident activity.

Incident occurrence -> Alert -> Investigation -> Response -> Post-incident activity

SAR incidents can occur suddenly and without warning, as a result of injury, mechanical failure, environmental conditions, or human error.

Once the incident has occurred, the subject in distress must signal for help. That signal for help – or distress alert – can be conveyed through a variety of mechanisms, including satellite-enabled notification technology such as COSPAS-SARSAT, radio communication relays, 1-800 numbers, cellular and satellite phones, 911 systems, police call centres, provincial/territorial points of contact, friends or family.

Regardless of the means by which an alert is conveyed, the recipient must then notify the proper SAR authority for investigation and response. The responsible agency will then validate key information regarding the incident in question. This process can involve establishing contact with the subject, determining their position, and assessing whether the situation warrants further action.

If the decision is made to launch a response, resources are tasked by the responsible agency. For most incidents, this means tasking resources under that agency’s control. However, it can also mean getting assistance from other partners, whether in the form of specialized resources, contracted services and vessels of opportunity, or volunteer augmentation.

Once SAR resources are released from the incident, or the case is transferred to another organization (such as the Transportation Safety Board, a criminal investigation team or the coroner’s office), redeployment and replenishment occurs. As a final step, the incident is recorded by the responding agency in some format.

| Type of SAR Incident | Lead Authority |

|---|---|

Aircraft incidents

|

Canadian Armed Forces |

Maritime incidents

|

Canadian Coast Guard |

Ground and Inland Water (GSAR)

|

Provincial/territorial governments; usually delegated to the police force of jurisdiction. |

SAR in National Parks, National Historic Sites and Marine Conservation Areas

|

Parks Canada Agency |

Air & Maritime Response Assets

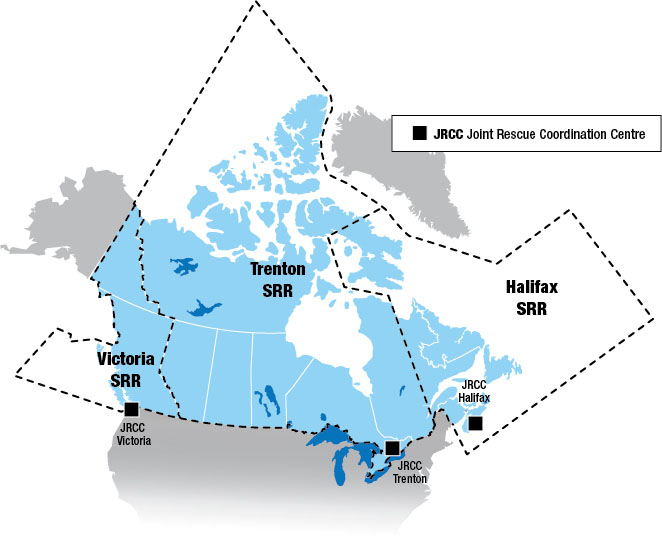

To coordinate the federal response in the aeronautical and maritime domains, the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Coast Guard have divided Canada’s SAR area of responsibility into three search and rescue regions. Each region has a Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (located in Halifax, Trenton and Victoria) manned by officials from the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Coast Guard, who maintain around-the-clock watch, ready to coordinate a joint response to aeronautical and maritime SAR incidents.

Joint Rescue Coordination Centres (JRCC)

Every year, the three Joint Rescue Coordination Centres coordinate responses to an average of more than 9,000 incidents. The figures listed below represent the total incidents coordinated by the Joint Rescue Coordination Centres (JRCCs) in the last five years, identified by Search and Rescue Region1.

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 5 Yr Avg | |

| Halifax | 2673 | 2665 | 2868 | 2651 | 2682 | 2707 |

| Trenton | 3278 | 3527 | 3710 | 3664 | 4110 | 3657 |

| Victoria | 3146 | 3166 | 2894 | 2868 | 3244 | 3063 |

| Total | 9097 | 9358 | 9472 | 9183 | 10,036 | 9429 |

The Canadian Armed Forces have SAR assets strategically located across the country, with five primary SAR squadrons at bases in Gander, Newfoundland & Labrador; Greenwood, Nova Scotia; Trenton, Ontario; Winnipeg, Manitoba; and Comox, British Columbia.

The Royal Canadian Air Force maintains both fixed-wing and rotary-wing air assets, ensuring the necessary flexibility to respond to the wide array of aeronautical and maritime SAR incidents that arise across the Canadian area of responsibility.

The primary SAR assets used by the Canadian Armed Forces include the following:

- 14 x CC130H Hercules Aircraft;

- 6 x CC115 Buffalo Aircraft;

- 14 X CH149 Cormorant Helicopters; and,

- 5 x CH146 Griffon Helicopters

All of the above-listed aircraft are multi-role; as such, only a select number of these aircraft are assigned to primary SAR duties at any given time. In exceptional circumstances, however, non-primary SAR CAF assets, including other aircraft, ships, or army units, can be called upon to serve as secondary SAR resources.

From wherever they are, around-the-clock, CAF SAR crews react immediately to a SAR incident, and there are set standards to which CAF assets are pre-positioned to respond on a daily basis. The CAF SAR crews are at a 30-minute response posture for 40 hours each week, in which the CAF SAR crews are to be airborne within 30 minutes. These periods of 30-minute readiness can be scheduled to coincide with anticipated peaks in SAR activity. For the remainder of the time, CAF SAR crews are to be airborne within 2 hours (as the aircrew may not be on base). Generally, CAF SAR crews are airborne well inside these timeframes.

The Canadian Coast Guard has a total of 117 vessels and 22 helicopters stationed across the country that can deliver maritime SAR services, either in a primary or secondary role.

The Canadian Coast Guard’s primary SAR assets include 40 SAR Stations, including one Air Cushioned Vehicle. To supplement this capacity during the summer months, the Canadian Coast Guard operates 25 Inshore Rescue Boat Stations across the country. The Canadian Coast Guard can also call on other multi-tasked vessels to contribute to the SAR program when required. Multi-tasked vessels are required to remain within a specific SAR area, and to maintain all SAR operational standards while they are multi-tasked.

Every Coast Guard vessel carries on board at least one Rescue Specialist, and all Coast Guard vessels are required to carry and maintain specialized SAR equipment.

Designated search and rescue units (SRUs), with specially trained crews, are operational on a 24/7 basis. These units will depart on a SAR tasking within 30 minutes or less, 99% of the time. At the SRU Sea Island in British Columbia, a specially trained crew provides diving services on a 24/7 basis. Inshore Rescue Boat units will also depart on SAR taskings within 30 minutes or less, 99% of the time, during their on-duty time. When in operational status, all other Coast Guard vessels will depart on SAR taskings within one hour of notification.

Ground Response Assets

In contrast with the federal partners, provincial and territorial governments do not maintain fleets of crewed aircraft and vessels that are on exclusive standby for search and rescue response. Existing police, fire, and emergency medical services assets are tasked on an as needed basis to assist with search and rescue incidents. Recognizing the unique demands of search and rescue response, some jurisdictions have developed specialized capabilities within their police, fire, and/or emergency medical services programs. For instance, virtually all police services that operate aircraft have equipped them with high-resolution video and forward-looking infra-red cameras, which are useful in detecting lost persons, day or night.

Government-owned aircraft may also be utilized from time-to-time in support of search and rescue, although few are specifically equipped for this role.

Moreover, across Canada, ground SAR is heavily reliant on volunteer organizations to provide the bulk of the human resources to support these efforts. In addition, federal assets can be requested by provinces and territories to assist in ground search and rescue operations, when required.

| BC | AB | SK | MB | ON | QC | NB | PE | NS | NL | NT | YT | NU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1338 | 82 | 19 | 318 | 80 | 6 | 75 | 150 | 78 | 20 | 178 |

While the responsibility for ground SAR throughout most of the country falls to the provinces and territories, Parks Canada does have a limited mandate for ground SAR within National Parks and National Historic Sites.

As such, Parks Canada maintains dedicated mountain rescue teams in Banff, Jasper, Kootenay, Glacier, Mount Revelstoke and Waterton Lakes National Parks, equipped with standard mountain-rescue equipment. In addition, cross-functional SAR teams are located at various locations across the Parks Canada system, covering all provinces and territories, including the eastern and western Arctic, and are equipped with standard ground SAR equipment.

Parks Canada uses a variety of external and internal resources for SAR, depending on the location of the site. The majority of Parks Canada equipment is not dedicated to SAR use, but may be utilized for SAR depending on the circumstances of the incident.

In 2011/12, Parks Canada responded to approximately 3600 visitor safety incidents, including lost persons, avalanche incidents, mountain rescues, boat accidents and medical incidents, in both front country and wilderness environments.

The Volunteer Contribution

The strong volunteer component of the NSP provides all levels of government with a greater set of resources to meet SAR requirements. In addition to providing critical manpower, the volunteers also represent the community’s link to municipal, provincial/territorial and federal organizations in the delivery of SAR services. Along with local authorities and police forces, volunteers have the unique local knowledge, expertise, and experience required for an effective response.

The volunteer base is the foundation for SAR in Nova Scotia. They are well-trained, motivated, and capable, and perform an invaluable service to the citizens of Nova Scotia.

Emergency Management Office

Nova Scotia

There are three key national SAR associations that help to support and guide Canada’s volunteer SAR community. Together, they represent some 18,000 volunteers across the country:

- The Civil Air Search and Rescue Association is a Canada-wide volunteer association dedicated to the promotion of aviation safety, and to the provision of air search support services to Canada’s National SAR Program. It provides air search support services to the Canadian Armed Forces, and has Memoranda of Understanding with all of the provinces to provide air search support services. The association represents 100 teams and 2,534 volunteers.

- The Canadian Coast Guard Auxiliary is a Canada-wide volunteer association dedicated to maritime SAR and the promotion of boating safety, and provides assistance to the Canadian Coast Guard in maritime SAR. The association represents 1200 units/vessels and 4,000 volunteers.

- Search and Rescue Volunteer Association of Canada was established by the Provincial and Territorial Associations to provide a national voice for ground SAR volunteers in Canada. It aims to address issues of common concern and to develop consistency and promote standardization or portability of programs and volunteers across the country. The association represents 300 teams and 12,000 volunteers.

Notes:

1 - These numbers do not include approximately 1,000 annual incidents that require JRCC investigation but that do not form a SAR case.

2 - Input for the QSR was not received from Alberta or Québec. Moreover, information on the number of search and rescue incidents varies highly from jurisdictionto jurisdiction given differences in how information is collected, and many police searches are not included in the above figures. As such, the numbersdepicted in this chart should be seen as indicative only. Parks Canada’s contribution to ground SAR (within its federal areas of responsibility) is reflected laterin this section.

V. Observations

Canadians can be confident that the National SAR Program continues to be one of the most effective in the world. The NSP is blessed with highly-skilled, dedicated and experienced SAR personnel that – in a genuine spirit of collaboration – are willing to work across jurisdictional boundaries to save lives. Moreover, the divided responsibilities, varied approaches and complementary capabilities between levels of government and across paid and volunteer organizations result in a fluid and flexible system, able to meet the diverse challenges that arise across the country. As a result, the Canadian SAR community is unquestionably greater than the sum of its parts.

Nevertheless, the life and death consequences of Search and Rescue operations – the “no-fail” characteristic of this mission – demand that program stakeholders remain committed to continuous improvement.

The observations that were offered by SAR stakeholders throughout this process covered a broad spectrum of issues including prevention, coordination and interoperability, volunteer support and data management. This breadth of input alone is indicative of the ongoing dedication of the SAR community across Canada to ensure that the system is working, and their thoughtful observations will provide a solid basis for its continuous improvement.

Prevention

Prevention is a critical line of activity within the National SAR Program. Efforts are being made across the NSP partnership to minimize the number and severity of SAR incidents in Canada by, inter alia, increasing awareness, mitigating risk, and changing behaviour to encourage Canadians to take responsibility for themselves in outdoor pursuits. Taken together, these efforts improve the safety of all, and optimize the use of NSP resources.

However, given that the responsibilities and authorities for prevention are not as clearly delineated as in the area of response, prevention efforts often fall secondary to response efforts, and collaboration across the system remains weak. This runs contrary to the logic that prevention should be at the forefront of an effective SAR program.

The importance of prevention must be re-emphasized as a core element of the NSP. Moreover, given that prevention activities permeate across the NSP partnership, a more holistic and coordinated approach to prevention should be pursued.

Response: Coordination, Compatibility and Interoperability

Although a SAR response is initiated by a specific organization – based on the nature and location of a SAR incident – the complete response is frequently multi-jurisdictional to ensure the most effective assets are deployed.

Critical to the success of this type of system is the ease and speed with which a responsible jurisdiction can access the most capable, timely and appropriate assistance. This, in effect, has been described as “seamless” SAR, wherein all issues are subordinate to the primacy of saving a life, and mutual aid – across organizations – stands as a fundamental principle of the system.

With that in mind, technology (i.e. sensors, radio communications, GPS/mapping, etc.) can serve as a force multiplier in enabling a more effective SAR response, however it can also give rise to interoperability challenges. As such, the introduction of new technologies must be carefully managed so as to ensure that they enhance – and do not detract from – the seamless delivery of SAR in Canada.

Moreover, going forward, NSP partners must ensure that effective mechanisms and procedures are in place to transmit distress signals to the appropriate responding agency in a timely manner. All partners should be intimately familiar with the protocols and procedures of the jurisdictions with which they engage, so that they know who to call, and how to call them.

Other initiatives to enhance interoperability could also be further pursued, with NSP partners collaborating in joint training, exercises and operations. Furthermore, opportunities for standardization (in training, qualifications, radio communications, or call-out procedures, for instance) could be explored, while remaining mindful of the benefits that the NSP – and indeed, all Canadians – derive from the diverse and tailored approaches to SAR that exist across the country.

Volunteers

Many Canadians are not aware of the substantial volunteer component of the NSP, and even fewer are aware of the significant investment – both in terms of time and money – that this commitment demands of its volunteers.

Our volunteers offer a critical conduit into the local community, raising awareness and promoting safety amongst Canadians. They also serve as an enormous asset, providing additional response capacity across the aeronautical, maritime and ground SAR domains. These volunteers are skilled and dedicated citizens, who commit their time to help ensure the safety and survival of their fellow Canadians. In many cases, they represent the backbone of Canada’s SAR system, as they are often the first to reach Canadians in peril.

Sustaining the volunteer cadre for the future must be a priority. This means recognizing these volunteers for their service to the country; it means ensuring they have the appropriate supports – and coordination mechanisms – in place to facilitate their work; and, it means actively attracting new volunteers for the future.

Data Management & Performance Measurement

There is currently no centralized or standardized accounting of search and rescue activities across Canada. Information on the rate of search and rescue incidents, their nature, and the effectiveness of the NSP response varies widely from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

At the most fundamental level, there is no commonly used definition of what constitutes a “SAR incident.” Is it a person in distress in an urban area? Does it include those requiring towing assistance? How do you account for false alarms and missing persons, which also require investigation? Complicating matters, various organizations compile and retain data using software that may not be connected to current SAR systems.

Accurate and comparable data on SAR incidents across jurisdictions in Canada would prove invaluable for charting the future course of the NSP. More specifically, it would improve shared understanding amongst SAR partners, better enable decision-making and command and control in each organization, and help to define where the real gaps and seams are in the system – both in terms of response and prevention.

The National Search and Rescue Secretariat continues to make progress with its SAR Knowledge Management System, which will serve as a central repository of information for the NSP and its stakeholders, and will serve as a decision support tool at the strategic and tactical levels. Work in this direction must continue.

Future Trends

As we move forward with the Quadrennial SAR Review process, we must be mindful of emerging trends that may have an impact on both the demand for SAR in Canada, and how we best respond to it.

For instance, the changing climate – including the increased frequency of extreme weather events – may have an impact on SAR in the coming years, requiring changes to how, where and when SAR resources are deployed.

Moreover, increased commercial and tourist activity in the North will demand a deeper awareness of the requirements and responsibilities for successful SAR in that region.

New technologies, in concert with supporting regulation, will present profound opportunities for improving SAR services in Canada through enhanced communications, detection, rescue, and survivability. In that vein, the international Medium Earth Orbit Search and Rescue System – to which Canada contributes – is a promising step forward.

However adoption of new technologies in a timely and consistent manner may prove difficult and/or costly, with potential ramifications for interoperability amongst partners.

At the same time, new technologies have the potential to create a false sense of security amongst the general public. For instance, with a GPS in hand, Canadians maybe more willing to trek into increasingly remote areas, thereby increasing the potential for a SAR incident.

Compounding this problem is the continued migration towards urban centres, resulting in a loss of “on land” knowledge amongst the general public.

Finally, the impact of an aging population on SAR incidents in Canada will need to be further tracked and assessed.

VI. Recommendations

Standardized reporting and improved data management across the NSP must continue to be pursued without delay, as it would serve to inform future decision-making, and would set the SAR community on the proper footing for successful reviews in the years to come.

As a fundamental and invaluable pillar of the National Search and Rescue Program, prevention efforts should be further emphasized and more effectively coordinated across the NSP partnership.

Given the substantial role played by volunteer organizations in the delivery of SAR excellence in Canada, this cadre of dedicated Canadians must be supported and sustained by the NSP partners.

To ensure ongoing “seamless” SAR delivery for Canadians, all NSP partners must continue to improve coordination, collaboration and interoperability across the system, including better leveraging existing mechanisms.

The National Search and Rescue Secretariat should further leverage the SAR New Initiatives Fund and the annual SARscene conference (a national event involving all NSP partners and volunteers) to support immediate measures, and – more importantly – to advance the national dialogue on these issues with the aim of identifying system-wide, sustainable solutions for the future.

VII. Conclusion

Canada is privileged to have one of the most effective SAR systems in the world, encompassing a wide array of partners with diverse capabilities and competencies. This complex mosaic of jurisdictions and responsibilities has evolved to meet the unique needs of the Canadian landscape, and the Canadian populace. While this network of partners comes with its challenges, it also represents a profound strength.

The system’s efforts in both prevention and response ensure that a wide spectrum of options is being pursued to keep Canadians safe. NSP partners are empowering Canadians to take personal responsibility for their safety. At the same time, they are ensuring that the appropriate response mechanisms and capabilities are in place for when prevention fails.

Going forward, we must standardize our reporting and improve our data management across the NSP partnership, to serve as the foundation on which future decisions regarding the NSP can be made, particularly as we come to face new challenges and opportunities in the future. As we pursue that effort, we must also re-double our efforts on prevention; acknowledge and support our critical volunteer base; and bolster our response efforts through enhanced cooperation, coordination and interoperability.

This inaugural Quadrennial SAR Review represents an important first step in developing a comprehensive perspective of the National SAR Program. The thoughtful input that was received from SAR stakeholders across the country is a testament to the enduring commitment of this community to improve the safety of Canadians. The dialogue that has been started through this process must continue as we chart the future course of the National SAR Program.

- Date modified: