Large-Scale Implementation and Evaluation of the Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS)

Large-Scale Implementation and Evaluation of the Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS) PDF Version (1 Mb)

Large-Scale Implementation and Evaluation of the Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS) PDF Version (1 Mb)

By James Bonta, Guy Bourgon, Tanya Rugge, Chloe Pedneault, & Seung C. Lee

Table of contents

- Author’s Note

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Results

- Discussion

- References

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Appendix D

- Appendix E

- Appendix F

- Appendix G

- Appendix H

- Appendix I

- Appendix J

Author’s Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Research Division

Public Safety Canada

340 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa ON K1A 0P8

Email: PS.CSCCBResearch-RechercheSSCRC.SP@ps-sp.gc.ca

Acknowledgements

This project formally began with a signing of a Memorandum of Understanding between Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Canada and British Columbia’s Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General on August 29, 2011. The first STICS training took place the following month. Over the course of nine years there were many, many individuals who contributed to the completion of this project. In the short space we have here we would like to give special recognition to a few of them.

First and foremost, we would like to extend our gratitude to the probation officers, coaches, STICS coordinators, their managers, and administrative staff. Their efforts to do the best they could and go the extra mile by following the research protocols, be it submitting audio recordings or completing research questionnaires, is deeply appreciated. Second, Bill Small’s leadership, commitment to RNR integrity, and his steady hand in guiding the Community Corrections Division throughout the implementation were stellar. Mr. Small played a vital role in making this initiative a success. Third, there is Carrie McCulley, Manager of Offender Programs in British Columbia. Carrie’s masterful organizational skills oversaw the scheduling of trainings and arranged the resources needed for the researchers, STICS coordinators, and coaches. We express our sincere thanks to her. Finally, Carmen Zabarauckas, then Director of Research Planning and Offender Programming for the Ministry in British Columbia, facilitated the secure transfer of thousands of provincial records and audio recordings to Public Safety Canada. She was an exemplar of inter-jurisdictional research collaboration.

At Public Safety Canada there was a small army of students and research assistants who collated data as it arrived, coded audio recordings, and organized various databases. They were invaluable and in particular we would like to express our appreciation to our colleague Leticia Gutierrez who was the “General” of this army. When we began STICS training, we were fortunate to secure government interchanges with the Province of Ontario to assign two of their probation officers to assist us with the trainings. We benefitted immensely from the expertise of Colleen Hamilton (2012-2013) and Liz Bourguignon who remained throughout the five years of trainings and refresher courses. We were fortunate to have two senior managers who were very committed to evidence-based policy. Shawn Tupper was our Assistant Deputy Minister and Mary Campbell our Director General at the time. They were unwavering in their support of STICS and ensured the financial resources to commit to the project. Finally, we must thank Amel Loza-Fanous, current Manager of Corrections Research, for believing in STICS and that the BC implementation research should reach a final conclusion with this report.

Declaration of Conflict of Interest: James Bonta, Guy Bourgon, and Tanya Rugge are co-authors of STICS. The copyright for STICS is held by the Government of Canada, and none of the authors receive royalties from this program. James Bonta receives royalties on sales of the Level of Service Inventory-Revised cited in this article.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-for-profit sectors.

Ethical approval: The research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Province of British Columbia and BC Corrections and the Canadian Tri-council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans.

Informed consent: Informed written consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Executive Summary

Following Martinson’s (1974) pessimistic review of offender rehabilitation programs, a number of researchers began to question his conclusion that treatment for offenders was ineffective. By 1990 there was a strong basis in evidence, and conceptually, that treatment can work. Perhaps the most influential perspective today on effective correctional rehabilitation is the Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) model first formulated by Andrews, Bonta, and Hoge (1990). Essentially, treatment is most effective when it is delivered to higher risk offenders (risk principle), targets criminogenic needs (need principle), and delivers interventions in a way that matches the offender’s abilities, motivations, and learning style, mostly using cognitive-behavioural techniques (responsivity principle). The evidence in support of RNR is robust and applicable to a range of offenders (e.g., sex offenders, women, youth).

Community supervision (i.e., probation and parole) is the most widely used correctional sanction in North America. However, the evidence of its effectiveness is equivocal, with one meta-analysis showing very little reduction in recidivism associated with community supervision (Bonta et al., 2008). A study of probation practices in Manitoba provided a possible explanation for these findings. After audio recording supervision sessions between a sample of probation officers (PO) and their clients, Bonta and his colleagues (2008) found that POs showed little adherence to the RNR principles. This evidence suggested that, if POs were trained to more closely follow RNR, better outcomes may follow.

Subsequently, researchers from Public Safety Canada (PS) developed a training model to enhance RNR adherence by POs. The training was called the Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision, or STICS. It was evaluated in a randomized experiment with the support of 52 volunteer POs from British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Prince Edward Island (Bonta et al., 2011). The POs audio recorded a sample of their supervision sessions, and a 2-year follow-up of their clients was conducted. The results demonstrated that the behaviour of the trained POs changed in the direction of better adherence to RNR principles, and client recidivism rates within a 2-year fixed follow-up period were significantly lower (25%) compared to the clients of the probation-as-usual group (40%).

Encouraged by the results from the 2011 evaluation, the Community Corrections Division of British Columbia decided to implement STICS across their probation service with the assistance of PS. Researchers from PS provided training to front-line POs as well as provincial coaches and STICS coordinators. PS was also responsible for the evaluation of the provincial roll-out of STICS. Training began in September 2011 and ended in February 2015. Approximately 350 POs were trained. For the evaluation, POs were asked to audio record supervision sessions (to measure behavioural change), and information on client recidivism was collected.

Analyses of the audio recordings showed clear changes in PO behaviour following training. POs spent a greater proportion of their sessions on criminogenic needs, especially procriminal attitudes/cognitions, and less on noncriminogenic needs and the conditions of probation. STICS training is intended to produce these types of behavioural changes. In addition to an improved focus on criminogenic needs (need principle), POs engaged in more cognitive-behavioural interventions (responsivity principle). Overall, STICS training was associated with better adherence to the RNR model.

Clients of STICS-trained officers were compared to a random sample of probationers supervised prior to STICS training (i.e., this comparison group of clients had minimal exposure to STICS). Clients of STICS-trained POs had a significantly lower 2-year recidivism rate than those who were supervised prior to STICS training. At two years, 43.0% of STICS clients had any new criminal conviction (14.9% of whom received a violent reconviction), whereas the rate for the non-STICS clients was 61.4% (21.2% with a violent reconviction). Addressing procriminal attitudes/cognitions in supervision sessions with clients and the use of cognitive interventions were particularly important in the reduction of recidivism. Every 10% increase in the proportion of each session spent discussing procriminal attitudes/cognitions resulted in approximately a 5% decrease in any new criminal reconvictions. Additionally, clients who were exposed to cognitive techniques were approximately 28% less likely to be reconvicted of a new criminal offence compared to clients who had not been exposed to cognitive techniques at all.

In summary, the implementation of the STICS model in BC can be seen as a reasonable success. PO behaviour followed more closely the RNR principles after training and client recidivism decreased. This project demonstrated that, with the proper resources and dedication to treatment integrity, a community corrections agency can benefit from an evidence-based approach to probation supervision. Hopefully, the results of this study will encourage other agencies to consider how best they can implement an RNR-based supervision model.

Introduction

Community supervision is one of the most common criminal justice sanctions in Canada. On any given day, there are more than 100,000 adults on community supervision, representing nearly 75% of the total correctional population (Malakieh, 2019). Given that most offenders are supervised in the community, community supervision is integral to the effectiveness of the correctional system. Probation and parole officers meet with clients regularly to manage their risk in the community and link them to appropriate supports. Logically, we would expect that community supervision contributes to public safety by lowering offenders’ likelihood of recidivism and some reviews suggest, with caveats, that supervision can reduce recidivism under certain conditions (Smith et al., 2018). However, in 2008, a quantitative review revealed that community supervision only produced an average reduction in recidivism of 2% and no reduction in violent recidivism (Bonta et al., 2008). To better understand these unexpected findings, Bonta and colleagues analysed the audio recordings of supervision sessions between 62 probation officers (PO) and their clients from the province of Manitoba. They found that the sessions typically did not follow the principles of effective offender rehabilitation known to reduce recidivism.

The Risk-Need-Responsivity (RNR) framework, first formulated in 1990 by Andrews, Bonta, and Hoge, has become one of the most influential models of correctional rehabilitation (Cullen, 2013; Polaschek, 2012; Wormith & Zidenberg, 2018). The risk principle involves matching the level of service (e.g., treatment, supervision) with the offender’s level of risk. That is, intensive services should be directed to the higher risk offenders and less intensive services to those who are low risk. The need principle maintains that interventions should target criminogenic needs (i.e., dynamic risk factors associated with recidivism), such as procriminal attitudes and substance abuse rather than targeting noncriminogenic needs such as self-esteem and indicators of personal distress. The responsivity principle aims to maximize learning by delivering interventions in a way that matches the offender’s abilities, motivations, and learning style, mostly using cognitive-behavioural techniques.

While studies of community supervision have found no or little impacts on recidivism, there is strong evidence that correctional treatment programs that adhere to the principles of RNR can produce large reductions in recidivism (Bonta & Andrews, 2017). For instance, correctional programs that adhered to principles of risk, need, and responsivity showed an average 26% reduction in recidivism compared to correctional programs that did not adhere to these principles. Evidence also suggests that RNR-based correctional programs are even more effective at reducing recidivism when they are delivered in the community, with community-based correctional programs showing an average 35% reduction in recidivism when they adhered to the principles of risk, need, and responsivity (Bonta & Andrews, 2017). Therefore, it seems the RNR framework represents a promising avenue for community supervision to produce greater reductions in recidivism.

Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS)

To capitalize on the success of RNR-based correctional treatment programs, a group of researchers at Public Safety Canada developed the Strategic Training Initiative in Community Supervision (STICS). STICS was designed to train POs in the principles of RNR. In accordance with the risk principle, STICS training is reserved for POs who supervise medium- and high-risk clients. The training itself includes a 3-day training curriculum that covers the risk, need, and responsivity principles, with an emphasis on addressing procriminal attitudes/cognitions (see Appendix A for a breakdown of the training modules). Attitudes and cognitions represent a major risk factor for future criminal behaviour and are considered to underlie all other criminogenic needs, such as substance abuse and family/marital relationships (Bonta & Andrews, 2017). In STICS training, officers are taught how to address procriminal attitudes/cognitions using cognitive and behavioural intervention techniques. This includes, for example, teaching concrete prosocial skills through modeling techniques, the use of effective reinforcement, and cognitive restructuring. During training, officers practice these skills and receive feedback from the trainers. After the initial training, newly developed skills are maintained through ongoing clinical support (Bourgon et al., 2010). Clinical support activities include personal feedback, refresher courses, and monthly meetings where specific skills are discussed (e.g., effective use of reinforcement).

To evaluate the effectiveness of the STICS model, a pilot study was conducted with POs who supervised adult offenders from the Canadian provinces of British Columbia (BC), Saskatchewan, and Prince Edward Island (Bonta et al., 2011). Eighty POs originally volunteered, but the final number decreased due to attrition (e.g., job change, promotion). The POs were randomly assigned to STICS training (after attrition, n = 33) or probation-as-usual (after attrition, n = 19). Post-intervention (i.e., STICS training), all participating POs were asked to audio record meetings with their medium- to high-risk clients throughout the first six months of supervision (once at intake, then three and six months later). Note that POs were free to select their clients for this study, leaving room for selection bias (e.g., contrary to the direction given, approximately five percent of the clients were low risk). Trained research assistants coded the recordings for topics of discussion (i.e., criminogenic needs, noncriminogenic needs, and probation conditions) and intervention techniques (e.g., cognitive and behavioural techniques).

STICS-trained officers spent significantly more time discussing criminogenic needs, particularly procriminal attitudes, and less time discussing noncriminogenic needs and probation conditions with their clients. Additionally, STICS-trained officers demonstrated higher levels of intervention skills than probation-as-usual officers, including the use of session structuring, relationship-building, and cognitive intervention techniques, but the use of behavioural intervention techniques did not differ between groups. Clients of the STICS trained officers had significantly lower 2-year recidivism rates than those of officers who did not receive STICS training (25% vs. 40%). Moreover, regardless of experimental condition, clients who had been exposed specifically to cognitive intervention techniques during their supervision sessions had significantly lower rates of recidivism after 2 years than those who did not (19% vs. 37%).

More recently, Bonta and colleagues (2019) attempted to replicate these original findings in the province of Alberta. POs were randomly assigned to STICS training (after attrition, n = 12) or probation-as-usual (after attrition, n = 15). In this study, medium- to high-risk clients were randomly assigned to POs to reduce the potential for selection bias (a source of bias in the 2011 study). POs were asked to audio record one session with their clients before training and three sessions (i.e., intake, then three and six months later) after training was delivered. Compared to the probation-as-usual group, STICS-trained POs focused more on procriminal attitudes during their sessions and less time discussing probation conditions. On the other hand, POs in the probation-as-usual group spent more time discussing other criminogenic needs, namely family/marital issues and substance abuse, than the STICS-trained POs. Additionally, STICS-trained POs showed significantly higher levels of relationship building and cognitive intervention skills when compared to probation-as-usual POs, but these groups did not significantly differ in terms of session structuring and behavioural intervention skills.

Overall, there was no difference in 2-year recidivism between clients supervised by the STICS-trained POs and those receiving probation-as-usual (52% for STICS and 49% for probation-as-usual). This may be because only a small increase in discussions of procriminal attitudes was observed across sessions involving STICS-trained POs; whereas, other criminogenic needs (e.g., family/marital issues) were discussed more extensively in sessions involving probation-as-usual POs. However, regardless of experimental condition, the use of cognitive intervention techniques was associated with reduced recidivism. Specifically, after controlling for age and risk, the average 2-year recidivism rate for clients exposed to cognitive interventions during their supervision sessions (43%) was significantly lower than for those who were not (54%). This finding is consistent with other research on community supervision where cognitive intervention techniques were used (Bourgon & Gutierrez, 2012; Labrecque et al., 2013; Robinson et al., 2012; Taxman 2008). More generally, meta-analyses suggest cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective with offenders (Landenberger & Lipsey, 2005; Wilson et al., 2005).

Present Study

The Community Corrections Division of the province of BC, one of the sites of the 2011 evaluation of the STICS demonstration project, was encouraged by the findings and decided to implement the STICS model across its jurisdiction. Therefore, whereas previous evaluations of the STICS model were based on demonstration projects, the current study examines the large scale implementation and evaluation of STICS across an entire jurisdiction. The system-wide rollout of STICS in BC began in September 2011. BC Community Corrections has two levels of POs: PO14 and PO24. In general, PO14s provide supervision services to low risk clients and often assist PO24s on various duties (e.g., establishing community work service, reviewing alternative measures). A PO24 supervises medium- to high-risk probationers and takes the lead in providing treatment intervention. In this study, all participating POs were at the PO24 level supervising medium- to high-risk probationers. We use the “PO” label for simplicity when referring to PO24 throughout the rest of this report.

The initial 3-day training was delivered to groups of 18-24 POs, approximately every six weeks. In addition to the POs receiving training, their managers also attended the training to show support but did not receive particular attention and feedback from the trainers. The provincial community corrections agency also created a structure to support the implementation by assigning five POs to a new full-time role as STICS Coordinators and 47 part-time coaches. The coordinators received intensive training from the trainers (e.g., train-the-trainer sessions), assisted with the delivery of trainings, gave POs individualized feedback on audio recordings, and provided clinical supervision to the coaches. The PO coaches were relieved from some of their duties to manage monthly meetings and provide individual feedback to staff in their respective offices. Additional POs were hired by the province to allow coaches to perform their new duties.

The current study examined the extent to which STICS training had an impact on PO behaviour, including the discussion of criminogenic needs (e.g., procriminal attitudes/cognitions) and the application of intervention techniques (e.g., cognitive-behavioural techniques). As all POs were to receive STICS training, we assessed PO behaviour pre- and post- training (i.e., single group pre- post-test design; Campbell & Stanley, 1966). Additionally, we examined the impact of STICS training and PO behaviour on client recidivism (i.e., quasi-experimental design; Campbell & Stanley, 1966).

Based on previous research, we hypothesized that PO behaviour would be more consistent with RNR after STICS training. Specifically, we expected that STICS-trained POs would spend more time discussing criminogenic needs with their clients and demonstrate improved intervention skills. We also hypothesized that exposure to STICS with better adherence to the principles of RNR would reduce client recidivism. In particular, based on previous evaluations of the STICS model, we hypothesized that exposure to cognitive intervention techniques would be associated with reduced client recidivism.

Method

POs were asked to audio record supervision sessions before attending training (pre-training audio recordings) and again after STICS training (post-training audio recordings; more details are provided in Procedures for Evaluating PO Behaviour). The recordings formed the basis for evaluating behavioural change among the POs. By February 2015, all POs with the BC Community Corrections Division had received the initial 3-day STICS training. In terms of ongoing clinical support, POs were expected to attend monthly meetings, as well as a refresher course once per year. They were also strongly encouraged to request individualised feedback from STICS coaches on their audio-recorded sessions with clients. Next, the procedures for evaluating (1) PO behaviour and (2) client recidivism are described, followed by the planned analyses.

Procedures for Evaluating PO Behaviour

Sample of POs

The potential pool of POs in BC consisted of 358 individuals. In total, 357 (99.7%) POs participated in the study to some extent. Demographic information was only available for a subset of POs who responded to a self-report questionnaire that was administered during training. Demographic information and other PO characteristics are presented in Table 1. POs were, on average, 41 years old (SD = 9.27, age range = 23-63, n = 283), female (64%), and Caucasian (79%). Almost all had a college or university degree and had an average of 10 years of work experience (SD = 7.08, range = 1-35, n = 287). Forty-seven POs were STICS coaches.

Audio Recordings

Pre-training Audio Recordings

Prior to attending STICS training, each PO was asked to audio record two probationers early in supervision (between one and three months) and two probationers later in supervision (three to six months) for a total of four recordings. Until the end of May 2013, the selection of these clients was left to the PO. That is, the clients were not randomly assigned. Starting in June 2013, the sampling strategy was revised such that clients were randomly assigned to POs by the duty officer. Specifically, as clients were sentenced and assigned to a probation office (a random court process), a duty officer identified any new admission that met the eligibility criteria. The duty officer then assigned the client to a PO who had not received STICS training. The duty officer also flagged one alternative or back up STICS client for each officer. The alternative client was used only if the first client was unable (e.g., absconds before recording Baseline Tape) or refused to participate. Unfortunately, the rate of refusals and characteristics of the clients who refused was not collected. This selection process continued until the PO had recorded one baseline session with four clients (two with clients earlier in their supervision and two with clients later in their supervision).

Post-training Audio Recordings

As clients were sentenced and assigned to a probation office (a random court process), a duty officer identified any new admission that met the eligibility criteria. The duty officer then assigned the client to a PO who had received STICS training. Each officer received one STICS client per month. The duty officer also flagged one alternative or back up STICS client per month for each officer. The alternative client was used only if the first client was unable (e.g., absconds before recording Tape 1 [i.e., intake]) or refused to participate. Unfortunately, the rate of refusals and characteristics of the clients who refused was not collected. This selection process continued each month until the PO had recorded at least one session with six clients (two medium-risk and four high-risk clients).

| % | n | /N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 36.1 | 104 | /288 |

| Female | 63.9 | 184 | /288 |

| Ethno-cultural background | |||

| Caucasian | 79.1 | 227 | /287 |

| Black | 0.3 | 1 | /287 |

| Asian | 4.2 | 12 | /287 |

| Aboriginal | 2.8 | 8 | /287 |

| Métis | 1.4 | 4 | /287 |

| East Indian | 8.7 | 25 | /287 |

| Hispanic | 0.3 | 1 | /287 |

| Othera | 3.1 | 9 | /287 |

| Education | |||

| High school | 0.4 | 1 | /285 |

| College/Undergraduate degree | 91.6 | 261 | /285 |

| MA Degree | 8.1 | 23 | /285 |

| STICS coach status | |||

| No | 86.8 | 310 | /357 |

| Yes | 13.2 | 47 | /357 |

| Office location | |||

| Interior/Fraser | 20.1 | 67 | /333 |

| Vancouver | 21.9 | 73 | /333 |

| Island/Coastal | 20.1 | 67 | /333 |

| Northern/Interior | 15.3 | 51 | /333 |

| Fraser/Metro | 21.6 | 72 | /333 |

| Headquartersb | 0.9 | 3 | /333 |

Notes. Ns vary as not all information was readily available, or the PO decided not to report.

a Other included one person each in the following self-specified categories: Caucasian/Aboriginal, Caucasian/Asian, East Indian/Caucasian, Middle East, Sikh, South Asian, South East Asian, “mixed”, and not specified.

b The three POs who identified as Headquarter staff were likely in the field and then were re-assigned to Headquarters.

The PO recorded the first post-training audio recording with a client (i.e., Tape 1) within 90 days from the start date of the client’s supervision order. Tape 2 occurred three months after the first tape, and Tape 3 was completed three months after Tape 2. The office manager was responsible for letting POs know when they needed to record a session with a client as well as noting reasons why a recording was not conducted (e.g., client transferred to another office).

Selecting Audio Recordings for Analysis

By the end of the training, over 2,800 audio recordings were submitted by POs (913 pre-training recordings and 1,756 post-training recordings). Resources did not permit coding all the recordings. Therefore, to ensure a representative sample of PO behaviour, at least one recording was randomly selected from each client. In total, 1,236 recordings from 1,112 individual clients were coded and analyzed (283 baseline and 953 post-training recordings). This selection process resulted in a median of two audio recordings per PO (Mean = 2.60, range = 1 - 9).

Coding Methodology

The randomly selected audio recordings were coded according to the content of the discussions and the skills demonstrated by the POs. The coding methodology was identical to that used by Bonta and his colleagues (2011, 2019). Teams of two coders listened to each five-minute segment of the recording and coded each segment for the presence or absence of specific content discussions and skills (described next). For a specific content discussion or skill to be scored as present, there had to be a minimum of two separate supporting statements (not simple yes/no answers to questions) within the five-minute segment. The coders also listened to the tape in its entirety to assess the overall quality of the session. Each coder conducted the scoring independently and then reached a consensus final score which was used for analyses. Scoring disagreements were discussed with a senior researcher for a final decision.

Fifty-eight audio recordings were randomly selected for inter-rater reliability analysis. The Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC; one-way random effect model) was calculated for continuous (i.e., ordinal) items and Cohen’s Kappa for categorical (e.g., yes/no) items. Cicchetti (1994; p. 286) has stated that when the ICC is between .60 and .74, “the level of clinical significance is good”. Therefore, an ICC value of .60 was set as the minimum criteria for including ordinal items in further analyses. Kappa was set at a value of .81 or higher (“almost perfect”; Landis & Koch, 1977, p. 165) as the minimum criteria for categorical items.

The average ICC for the discussion content areas was .77 with all areas meeting minimum ICC criteria except for antisocial personality pattern (ICC = .43); therefore, we excluded this content area from analyses. The average ICC for the intervention skills items was .59; we exclude the items that did not meet the minimum ICC criterion, including three collaboration skills items (from a total of 5 items), three structuring skills items (total of 8 items), and two behavioural skills items (total of 7 items). Fourteen intervention skills items had ICCs exceeding .60. All Kappas were .84 or higher.

Discussion Content Areas

First, all audio recordings were coded for the presence or absence of discussions surrounding probation conditions, noncriminogenic needs, and attitudes/cognitions. The STICS model emphasizes the importance of addressing procriminal attitudes/cognitions with all clients because this criminogenic need is thought to underlie all other criminogenic needs. In contrast, POs are taught to spend less time discussing probation conditions and noncriminogenic needs (e.g., housing, mental health) unless the client requires immediate attention to those areas. Second, if a criminogenic need was identified as a problem for a client, that client’s audio recordings were also coded for the presence or absence of discussions surrounding that criminogenic need. The criminogenic needs that were assessed were the following: antisocial personality pattern, procriminal attitudes, procriminal associates, family/marital, employment/education, and substance abuse. Because the provincial risk/need assessment instrument did not measure the client’s involvement in prosocial leisure and recreational activities, the criminogenic need of leisure/recreation was not coded. Additionally, as previously noted, antisocial personality pattern did not meet our minimum ICC criterion and was not included in further analyses.

Correctional Intervention Skills

All intervention skills items were rated as absent or present. If the skill was present, the quality of the skill was also rated on a 7-point scale from low-quality (1) to high-quality (7). Therefore, scores on each intervention skill item could range from 0 (absent) to 7 (high-quality). The first intervention skill that was constructed was collaborative skills. In the original STICS evaluation (Bonta et al., 2011), it was referred to as “relationship skills,” but three out of the five “relationship skills” items did not meet our minimum ICC criterion in the current study (Bonta et al., 2011 did not employ minimum ICC criteria for inclusion of items). The two items that remained were “role clarification” and “agreement on goals”, which more clearly reflect collaboration rather than relationship skills. Role clarification involves explaining the role of the PO as both helper and officer of the court, as well as discussing the expectations of the client during the probation period. Agreement on goals involves a collaborative discussion of what the PO and client would like to accomplish during the supervision period. Scores on both items were summed to create a collaborative skills score; therefore, scores could range from zero to 14.

The second intervention skill pertains to the structure of the session. A score for session structuring skills was constructed from the following five items: 1) session check-in, 2) review of the previous session, 3) review of homework assigned at the last session, 4) summarizing the current session, and 5) assigning homework. These five items reflect the steps that should be followed in almost all supervision sessions according to the STICS model, with the exception of a session during which a client presents with an acute crisis. Items were summed to create a total score, with scores ranging from zero to 35.

Next, we examined cognitive and behavioural intervention skills. One of the primary goals of STICS is to facilitate the learning and application of cognitive-behavioural techniques by POs. As in previous research (Bonta et al., 2011, 2019), separate scores were created for the cognitive and behavioural domains. Cognitive interventions refer to those that target thinking and use cognitive restructuring techniques to replace procriminal thinking with prosocial thinking. We created a total score for cognitive intervention skills by summing scores on four items. The first item reflects the PO’s effectiveness in teaching the client the relationship between their thoughts and behaviour. The remaining items measured different approaches for targeting and changing procriminal attitudes, including the identification of procriminal thinking patterns and generating prosocial thoughts and behaviours to replace procriminal thinking patterns. Ratings were summed to create a total score for cognitive skills; scores could range from zero to 28.

Behavioural interventions involve the use of effective reinforcement as well as homework or behavioural practice to develop concrete skills. Five items assessed behavioural intervention techniques, including the use of effective reinforcement (i.e., giving a reward or removing a cost to reinforce prosocial behaviour), effective disapproval (i.e., explaining to the client why one does not approve of specific behaviour and the consequences of that behaviour), rehearsal strategies (i.e., practicing new behaviour), homework to reinforce what was taught such as writing down problematic thoughts when they occur, and summarizing the session for the client at the end of each meeting. Scores were summed, with total scores ranging from zero to 35.

We also created a composite score for cognitive-behavioural techniques by summing total scores for cognitive and behavioural skills (scores could range from zero to 63). Additionally, we created a composite score that encompassed all intervention skills, including cognitive-behavioural, collaborative, and structuring skills, which we called total effective correctional skills (scores could range from zero to 98). Because we combined multiple items into scores for the various intervention skills, we assessed the internal consistency of these composite scores using McDonald’s omega (ω). Omega values ≥ .60 are commonly considered acceptable for research purposes, but values ≥ .70 are preferable, and values ≥ .80 are exemplary (Ponterotto & Ruckdeschel, 2007). Omega values were in the acceptable range for structuring skills (ω = .66; 5 items), cognitive skills (ω = .74; 4 items), behaviour skills (ω = .63; 5 items), combined cognitive-behavioural skills (ω = .68; 9 items), and total effective correctional skills (ω = .61; 14 items). As there were only two collaborative skills items, we calculated the inter-item correlation for these two items and found a weak association (r = .10), indicating poor internal consistency.

Participation in Clinical Support Activities

Officers were expected to participate in ongoing clinical support activities after attending the initial STICS training. Participation in these activities is an important part of the STICS model as they allow POs to maintain and improve their skills (Bonta et al., 2011; Bourgon et al., 2010). The level of participation in clinical support activities was to be assessed based on the frequency with which POs participated in the following activities: monthly meetings, refresher courses, and requests for personal feedback on their audio recordings. However, there were some issues with data quality, which we discuss later.

Procedures for Evaluating Client Recidivism

Audio Recorded Clients

There were a total of 1,112 audio recorded clients in this study. Of these clients, 283 started supervision with a PO before the PO attended STICS training (Recorded [R]-Baseline group) and 829 were supervised by POs after training (i.e., R-STICS group). R-Baseline and R-STICS clients had very similar demographic characteristics (see Table 2a). For example, more than 80% were male, two-thirds were Caucasian, and about half did not complete high school. Statistically significant differences between the groups were found for age and risk (from the Criminal History subscale of the Level of Service Inventory-Revised [LSI-R] to be described later, see Table 2b). Specifically, the R-STICS clients were about one and a half years older than R-Baseline clients. Additionally, R-STICS clients scored higher risk to reoffend compared to R-Baseline clients.

Furthermore, as a result of the short timeframe within which all POs had to receive STICS training, 65.7% of R-Baseline clients may have been exposed to STICS to some extent because their probation order extended beyond the date of their PO’s STICS training and they were not reconvicted prior to the PO’s training (see Appendix B for more details regarding overlap between baseline probation period and exposure to STICS-trained POs). Additionally, whereas all R-STICS clients were randomly assigned to POs, 40% of R-Baseline clients were selected by the POs before random assignment was implemented. These limitations are further addressed in the next section and in the Discussion.

Non-Recorded Clients

To address the issues raised in using the R-Baseline as a control group, we randomly selected a sample of non-recorded pre-STICS clients (NR-Baseline; n = 467). That is, clients who started supervision with a PO before the PO attended STICS training and whose supervision sessions were not audio recorded. Unlike R-Baseline clients, there was no selection bias because NR-Baseline clients were all randomly selected from historical records. Additionally, there was less potential exposure to STICS for NR-Baseline (40.3%) than R-Baseline clients (65.7%). We believe that these differences likely make NR-Baseline clients more representative of the pre-STICS population of probationers than R-Baseline clients. Criteria for selecting NR-Baseline clients were as follows: (a) effective date of the client’s community supervision order(s) must have been between 730 and 60 days before the PO attended the STICS training, (b) PO must have been listed as a supervisor for the client at least once during this timeframe, (c) the client’s supervision order had to have a total duration of one year or more at the start of their supervision term, (d) the client must have had a supervision assessment rating of medium or high at the start of supervision, and (e) the client could not be included in the group of R-Baseline clients. The NR-Baseline clients were comparable to R-STICS clients in terms of personal and criminal history demographics (Table 2a), except for age and risk scores (Table 2b).

Recidivism

Recidivism was defined as any new reconviction from the date of the client’s first audio recording for the audio recorded groups, and the effective community supervision start date for the NR-Baseline group, to the end of the follow-up period (i.e., the end date of national and/or provincial criminal records)Footnote 1. As the start of the follow-up period differed across groups, we controlled for the time offence free in the community before selection into the study (i.e., the start of the follow-up period) when estimating recidivism rates. Recidivism was separated into administrative (e.g., breach of probation conditions), non-violent (e.g., theft), and violent (e.g., assault) reconviction categories. If there were multiple categories within the same sentencing occasion, the category involved in the most severe offence (i.e., violent > non-violent > administrative) was selected. General recidivism encompasses violent, non-violent, and administration of justice convictions. Violent recidivism encompasses only violent convictions.

Our primary source of recidivism information was the national criminal history records held by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). The advantage of RCMP records is that they capture convictions across Canada and are not limited to a particular province. Another advantage is that the recidivism results can be compared to earlier evaluations of STICS completed in Canada that used the same indicator of recidivism. However, RCMP records were not available for all participants; there were 74 cases with missing criminal history records. For the missing cases, we searched the provincial database enabling 72 of the 74 cases to be coded. Therefore, in total, there were only two probationers for whom we had no follow-up information.

| R-STICS | R-Baseline | NR-Baseline | Cramer’s V | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | n | /N | % | n | /N | % | n | /N | R-STICS vs. R-Baseline | R-STICS vs. NR-Baseline | |

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 84.4 | 693 | /821 | 81.3 | 213 | /262 | 87.7 | 407 | /464 | ||

| Female | 15.6 | 128 | /821 | 18.7 | 49 | /262 | 12.3 | 57 | /464 | ||

| Gender – Group differences | .04 | .05 | |||||||||

| Ethno-cultural background | |||||||||||

| Caucasian | 62.3 | 512 | /822 | 65.9 | 182 | /276 | 59.2 | 273 | /461 | ||

| Indigenous | 28.6 | 235 | /822 | 23.9 | 66 | /276 | 29.5 | 136 | /461 | ||

| Othera | 9.1 | 75 | /822 | 10.1 | 28 | /276 | 11.3 | 52 | /461 | ||

| Ethno-cultural background – Group Differences | .05 | .04 | |||||||||

| Marital status | |||||||||||

| Single | 66.3 | 536 | /809 | 71.7 | 195 | /272 | 68.7 | 311 | /453 | ||

| Married or common law | 22.9 | 185 | /809 | 17.3 | 47 | /272 | 18.5 | 84 | /453 | ||

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 10.9 | 88 | /809 | 11.0 | 30 | /272 | 12.8 | 58 | /453 | ||

| Marital status – Group differences | .06 | .05 | |||||||||

| Education | |||||||||||

| No high school degree | 53.4 | 425 | /796 | 49.6 | 132 | /266 | 58.5 | 261 | /446 | ||

| High school degree | 34.4 | 274 | /796 | 36.5 | 97 | /266 | 30.7 | 137 | /446 | ||

| College/university | 12.2 | 97 | /796 | 13.9 | 37 | /266 | 10.8 | 48 | /446 | ||

| Education – Group differences | .03 | .05 | |||||||||

| Index offence type | |||||||||||

| Violent | 47.6 | 410 | /827 | 45.2 | 128 | /283 | 50.9 | 222 | /436 | ||

| Non-violent | 38.5 | 318 | /827 | 41.0 | 116 | /283 | 40.8 | 178 | /436 | ||

| Administration of justice | 12.0 | 99 | /827 | 13.8 | 39 | /283 | 8.3 | 36 | /436 | ||

| Index offence type – Group differences | .04 | .06 | |||||||||

| Any history of sexual crimes | |||||||||||

| Yes | 6.5 | 54 | /829 | 5.7 | 16 | /283 | 5.8 | 24 | /464 | ||

| No | 93.5 | 775 | /829 | 94.3 | 267 | /283 | 94.2 | 437 | /464 | ||

| Any history of sexual crimes – Group differences | .02 | .01 | |||||||||

Note. R-STICS = Recorded STICS clients. R-Baseline = Recorded baseline clients. NR-Baseline = Non-recorded baseline clients.Cramer’s v is a measure of the strength of association between categorical variables (0 ≤ v ≤ 1); v < .10 indicates that the strength of association from chi-square analyses is negligible. None of the Cramer’s v values were statistically significant.

a Other ethno-cultural groups for R-STICS, R-Baseline, and NR-Baseline, respectively, included East Indian (n = 28, 12, and 22), Asian (n = 15, 7, and 10), Black (n = 13, 4, and 12), Hispanic (n = 8, 1, and 5), and Other (n = 11, 4, and 3); these groups were merged to allow for statistical comparisons between client groups.

| R-STICS (n = 829) | R-Baseline (n = 283) | NR-Baseline (n = 467) | R-STICS vs. R-Baseline Cohen’s d [95% C.I] | R-STICS vs. NR-Baseline Cohen’s d [95% C.I] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Age (year) | 36.59 | 10.55 | 35.05 | 11.52 | 35.34 | 10.21 | 0.14 [0.01, 0.28] | 0.12 [0.01, 0.23] |

| LSI-R (Criminal History sub-scale) | 5.56 | 2.27 | 4.62 | 2.62 | 5.06 | 2.53 | 0.40 [0.26, 0.53] | 0.21 [0.10, 0.32] |

| Follow-up time (yrs) | 3.83 | 1.04 | 4.21 | 0.83 | 2.97 | 1.03 | 0.39 [0.25, 0.53] | 0.82 [0.71, 0.94] |

Notes. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. CI = confidence interval. LSI-R = Level of Service Inventory-Revised. Bolded values indicate effect sizes with CIs that do not include zero, indicating statistical significance (p < .05).

Analytic Plan

Our first primary research question examined whether STICS training was associated with changes in PO behaviour, including differences in the content of discussions with clients and the quality of intervention skills. To address this question, POs’ pre- and post-training audio recordings were compared to determine within-person changes in the proportion of time spent discussing criminogenic and noncriminogenic needs, as well as the quality of intervention skills. Therefore, only POs who submitted both pre- and post-training audio recordings were included in these analyses.

The proportion of 5-minute segments a content area was discussed was computed by dividing the number of 5-minute segments in which the topic was discussed by the total number of 5-minute segments within a session. The proportion of each session where a topic was discussed was then aggregated at the PO level for pre- and post-training audio recordings separately. For example, if a PO submitted more than one post-training audio recording, we averaged proportions for each content area over all post-training recordings for all recorded clients, resulting in a single mean proportion for each content area. Similarly, intervention skills were aggregated at the PO level for pre- and post-training audio recordings separately.

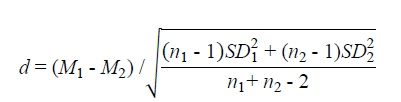

For all comparisons, Cohen’s d was computed as a measure of effect size as follows:

Equation for Cohen’s d

Image Description

Cohen’s d equals M1 minus M2, divided by the square root of the following fraction: the product of SD1 squared and one less than n1 plus the product of SD2 squared and one less than n2, divided by the sum of n1 and n2 minus 2.

Where M1 represents the mean for the post-training recording, M2 represents the mean for the pre-training recording, n1 and n2 are the sample sizes for post- and pre-training recordings, and SD1 and SD2 are the standard deviations for post- and pre-training recordings, respectively. Positive d values indicate an increase in discussion content or improvement in intervention skills. Cohen (1992) proposed heuristic values for interpreting d, with 0.2 corresponding to a small effect, 0.5 to a medium effect, and 0.8 to a large effect. Also computed was the 95% confidence interval (CI) for d. Confidence intervals that include zero indicate no statistically significant difference.

The second primary research question examined whether supervision by a trained PO was associated with a reduction in client recidivism. We addressed this question in two ways. First, we compared the recidivism rates of R-STICS clients (i.e., audio recorded clients exposed to a PO who received STICS training) with the recidivism rates of NR-Baseline clients (i.e., non-audio recorded clients randomly selected from the POs caseload prior to STICS training). As previously mentioned, the NR-Baseline clients are likely more representative of the PO caseload prior to STICS training than R-Baseline clients, and they were less likely to have been exposed to a STICS-trained PO during the study period. Second, for all clients who were audio-recorded (R-STICS and R-Baseline), we examined the relationship between actual PO behaviour captured during the audio-recorded sessions (i.e., discussion content and intervention skills) and client recidivism. This allowed us to explore whether some PO behaviours were more strongly associated with client recidivism than others.

Both a 2-year fixed follow-up as well as varying follow-up periods were used to evaluate recidivism outcomes. For the fixed 2-year follow-up, groups were compared on observed recidivism rates and also with logistic regression analysis to examine the association between STICS training and recidivism while controlling for covariates (described later). Odds ratios (expB1) indicate the change in relative risk associated with a one-unit change in the predictor variables. An odds ratio below 1 indicates that R-STICS clients have lower recidivism rates, and vice versa. No association is indicated when the 95% CI of the odds ratio contains 1. The B0 (an intercept value) represents the expected recidivism rate for the NR- or R-Baseline group in logit units, which could be converted to a probability (1/[1+exp(-B0)]). Also calculated were the expected recidivism rate at any specific level of a predictor variable (e.g., 1/[1+exp(-(B0+B1))]).

Cox regression survival analysis was used to examine the effect of STICS training on recidivism rates at varying times (Allison, 1984). Hazard ratios [HR] indicate how much the rate of recidivism increases or decreases based on the predictor variables after controlling for varying follow-up times. An HR below 1 indicates that R-STICS clients (or clients with more exposure to specific content/skills) had a lower recidivism rate than NR-Baseline clients (or clients with less exposure to specific content/skills). When computing time to recidivism for survival analyses, the new offence sentencing date was used to determine the time to recidivism.

Covariates known to be associated with recidivism were applied in regression and survival analyses. First, the Criminal History subcomponent of the Level of Service Inventory-Revised (LSI-R; Andrews & Bonta, 1995) was used to control the significant differences in offender risk between the groups. The Criminal History sub-component consists of 10 historical items scored 0 for absent and 1 for present and was based on file review. The Criminal History score predicted recidivism in our sample moderately well (AUC = .66; 95% CI = .63, .69). Second, we controlled for time offence-free in the community before selection into the study. This is an important confound because, as time offence-free in the community increases, the risk of recidivism decreases (regardless of the client’s initial level of risk; Flores et al., 2017; Hanson et al., 2018). The third control was for client age at the start of the probation period (Hanson, 2002; Hirschi & Gottfredson, 1983; Sampson & Laub, 2003).

In addition to our main research questions, we asked whether participation in clinical support activities improved the quality of discussions between POs and their clients. The STICS model and the psychology of human learning assume that behaviour improves with ongoing training and practice. Therefore, we expected POs who participated in more clinical support activities to demonstrate higher STICS-related behaviours and better outcomes with their clients than those who had lower participation rates. On a related note, we would expect that, as the implementation of STICS becomes more embedded within the organization, better outcomes (e.g., reduced recidivism) would result. Implementation research suggests that it could take a number of years to see demonstration project results replicated in large-scale implementations (Bierman et al., 2002; Fixsen et al., 2001, 2005).

Results

Impact of Training on PO Behaviour

Of the 357 POs who participated in this study, 201 submitted samples of both pre-training and post-training audio recordings (35 POs only submitted baseline recordings, and 121 POs only submitted post-training recordings). For this subset, post-training recordings (M = 24.55, SD = 8.60) were significantly longer on average than pre-training recordings (M = 18.60, SD = 9.52, d = 0.66, 95% CI [0.46, 0.86]). The mean proportion of 5-minute segments during which a topic was discussed pre- and post-training is presented in Table 3. On average, POs discussed noncriminogenic needs and probation conditions significantly less frequently after STICS training. Because attitudes/cognitions were the primary focus of STICS training, we examined the extent to which all POs addressed attitudes/cognitions in each session, regardless of whether they identified attitudes/cognitions as a criminogenic need for the client. A large difference was observed from pre- to post-training for attitudes, with POs discussing attitudes/cognitions with their clients for a significantly higher proportion of each session after STICS training.

| Discussion area | n | Pre-training M (SD) | Post-training M (SD) | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probation conditions | 201 | .38 (.32) | .30 (.22) | - 0.29 [-0.49, -0.09] |

| Noncriminogenic | 201 | .51 (.29) | .36 (.21) | - 0.59 [-0.79, -0.39] |

| Probation and noncriminogenic | 201 | .60 (.26) | .51 (.21) | - 0.38 [-0.58, -0.18] |

| Any and all criminogenic needs | 201 | .39 (.25) | .47 (.21) | 0.35 [0.15, 0.54] |

| Attitudes/cognitions – All sessions | 201 | .02 (.10) | .18 (.18) | 1.10 [0.89, 1.31] |

| Criminogenic need identified for the clienta | ||||

| Attitudes/cognitions | 51 | .02 (.10) | .18 (.20) | 1.01 [0.60, 1.42] |

| Peers | 123 | .18 (.22) | .17 (.18) | - 0.05 [-0.30, 0.20] |

| Family/marital | 84 | .27 (.25) | .21 (.20) | - 0.27 [-0.57, 0.04] |

| Employment/education | 74 | .28 (.27) | .21 (.19) | - 0.30 [-0.62, 0.02] |

| Substance abuse | 148 | .35 (.31) | .22 (.21) | - 0.49 [-0.72, -0.26] |

Notes. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. CI = confidence interval. Bolded values indicate effect sizes with CIs that do not include zero, indicating statistical significance (p < .05).

a POs had to have identified the criminogenic need in at least one baseline and one post-training client to be included in these analyses (see Appendix C for the frequency with which POs identified criminogenic needs pre- and post-training, respectively).

For the remaining criminogenic needs, we only examined sessions with clients for whom the criminogenic need was identified as a problem area. This reduced the sample size for each criminogenic need because only POs who identified the criminogenic need for at least one client pre- and post-training were included in these analyses. A large difference in the discussion of attitudes pre- to post-training was observed when attitudes were identified as a criminogenic need, with attitudes/cognitions being discussed for a significantly higher proportion of each session after training. Small to moderate effect sizes were observed for family/marital, employment/education, and substance abuse, such that these criminogenic needs were discussed less frequently post-training; however, the 95% confidence intervals for family/marital and employment/education included zero indicating a non-significant difference. Discussions of procriminal peers did not differ regardless of training.

Similar to discussion areas, we examined within-PO changes in intervention skills from pre- to post-training. Mean pre-training and post-training scores on each skill are presented in Table 4. Moderate to large effect sizes were observed across all intervention skills. Specifically, the quality of collaborative skills, session structuring skills, and cognitive and behavioural intervention techniques significantly improved after training. Notably, the average quality rating for total effective correctional skills almost doubled from pre- to post-training.

| Skill | n | Pre-training M (SD) | Post-training M (SD) | Cohen’s d [95% CI] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative | 201 | 0.72 (1.43) | 2.27 (1.99) | 0.89 [0.69, 1.10] |

| Structuring | 200 | 6.77 (3.22) | 9.55 (4.09) | 0.76 [0.55, 0.96] |

| Cognitive | 201 | 0.03 (0.16) | 1.71 (2.36) | 1.00 [0.80, 1.21] |

| Behavioural | 200 | 3.54 (2.41) | 6.62 (3.31) | 1.06 [0.85, 1.27] |

| Cognitive-behaviourala | 200 | 3.57 (2.42) | 8.35 (4.82) | 1.25 [1.04, 1.47] |

| Total effective correctionalb | 200 | 11.03 (5.46) | 20.15 (8.65) | 1.26 [1.05, 1.48] |

Notes. M = mean. SD = standard deviation. CI = confidence interval. Bolded values indicate effect sizes with confidence intervals that do not include zero indicating statistical significance (p < .05).

a Sum of cognitive and behavioural skills.

b Sum of collaborative, structuring, and cognitive-behavioural skills.

Impact of STICS on Client Recidivism

First, we compared recidivism rates for NR-Baseline and R-STICS clients. The average length of the follow-up period was 3.5 years (SD = 1.1; ranged from 0.1 to 5.8). Criminal history records for the NR-Baseline clients were requested earlier from the RCMP and thus had an earlier end date. As a result, the average follow-up period for NR-Baseline clients was shorter (M = 2.97 years, SD = 1.03) than for R-STICS clients (M = 3.83, SD = 1.04; t [968.42] = 14.29, p < .001, d = 0.88; Table 2b). Overall, approximately half (52.7%) of the clients from the two groups were reconvicted of a new offence at some point within the follow-up period. Categorized according to the most serious offence, 24% of reconvictions were for violent offences, 40% for nonviolent offences, and 36% for administrative offences (e.g., breach of conditions). The fixed 2-year general recidivism rate was significantly lower for the R-STICS clients (43.0%) compared to the NR-Baseline clients (61.4%) as was the violent recidivism rate (14.9% vs. 21.2%). Similar trends were observed after controlling for age, risk, and time offence-free in the community (see Table 5).

| Observed Recidivism Rates | Adjusted Recidivism Ratesa | OR [95% CI] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NR-Baseline % (n/N) | R-STICS % (n/N) | NR-Baseline % | R-STICS % | ||

| General Recidivism | 61.4 (243/396) | 43.0 (343/798) | 60.4 | 42.7 | 0.49 [0.37, 0.65] |

| Violent Recidivism | 21.2 (84/396) | 14.9 (119/798) | 18.9 | 13.5 | 0.67 [0.47, 0.95] |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (p < .05).

a The recidivism rates of NR-Baseline and R-STICS groups were estimated by logistic regression analysis after controlling for age (36 years old), criminal history (LSI-R; an average score of 5), and time offence-free (0 month). Logistic regression analysis was conducted based on the 396 NR-Baseline and 795 R-STICS clients with data available for all model variables.

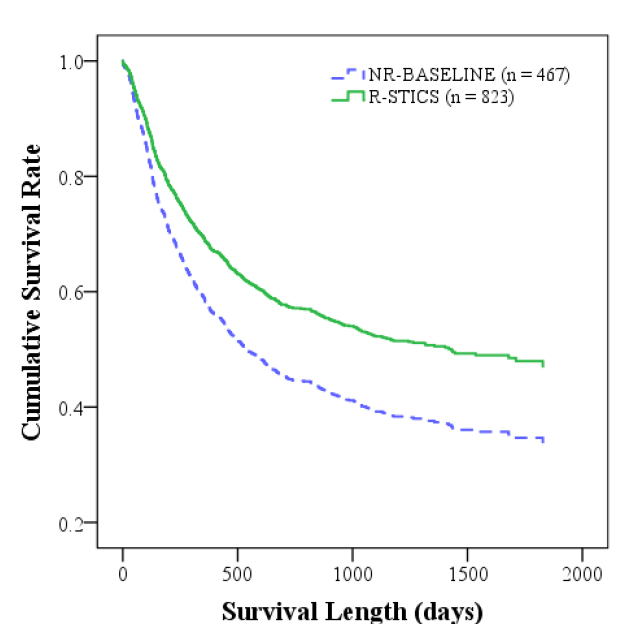

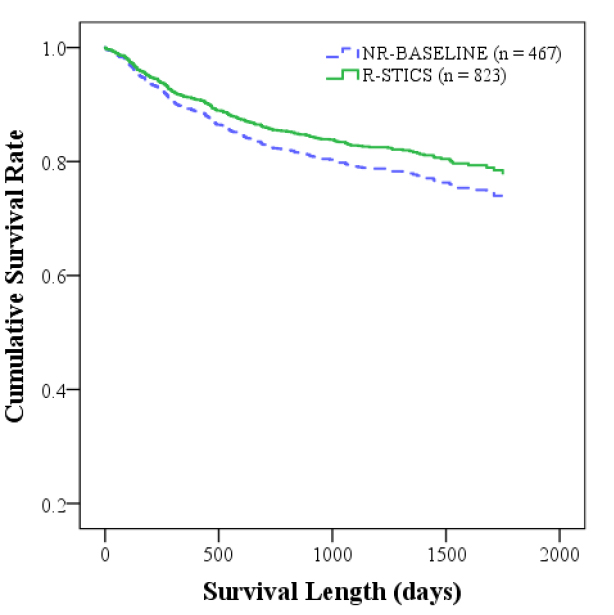

A limitation of using fixed follow-up periods is lower power due to reduced sample size and a loss of valuable information gained from longer follow-ups. To address these limitations, we examined the relationship between group (NR-Baseline vs. R-STICS) and recidivism using Cox regression controlling for important client characteristics (see Table 6). As expected, higher risk scores on the LSI-R Criminal History subscale predicted higher recidivism rates across all clients. Additionally, younger age predicted higher recidivism rates, whereas more time offence-free in the community before being selected into the study predicted lower recidivism rates. After controlling for these variables and varying follow-up time, R-STICS clients had significantly lower general recidivism rates (Wald χ2 [1] = 15.84, p < .001; see Table 6)Footnote 2. At any point during the follow-up period, R-STICS clients were 31% less likely to be reconvicted of any new offence compared to NR-Baseline clients (this rate was constant over time, Wald χ2 [1] = 0.33, p = .86). Although violent recidivism tended to be lower among R-STICS clients than NR-Baseline clients, this difference was not statistically significant (Wald χ2 [1] = 2.34, p = .14). Visual displays of the survival curves for (a) general and (b) violent recidivism events for NR-Baseline and R-STICS groups are presented in Appendix E.

| Variables | General Recidivism | Violent Recidivism | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| NR-Baseline vs. R-STICSa | 0.69 | [0.58, 0.83] | 0.81 | [0.61, 1.11] |

| Criminal history subscale (LSI-R) | 1.17 | [1.13, 1.22] | 1.13 | [1.07, 1.19] |

| Age (year) | 0.97 | [0.97, 0.98] | 0.96 | [0.95, 0.98] |

| Time offence-freeb (month) | 0.96 | [0.93, 0.99] | 1.00 | [0.96, 1.04] |

Note. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (p < .05).

a Cox regression analysis was conducted based on the 467 NR-Baseline and 823 R-STICS clients with data available for all model variables.

b Month(s) between the effective supervision start date and the first audio recording date for R-STICS clients.

Next, we examined the relationship between STICS and recidivism using the secondary comparison group consisting of the recorded clients who started supervision with a PO before the PO attended STICS training (R-Baseline). Unlike with the randomly selected NR-Baseline clients, the general and violent recidivism rates of R-Baseline clients were comparable (even slightly lower) to those of R-STICS clients (see Appendix F for observed and adjusted fixed 2-year recidivism rates). Specifically, after controlling for age, criminal history, and time offence-free, there was no significant difference in 2-year recidivism rates between R-Baseline and R-STICS clients for general (odds ratio = 1.26, 95% CI [0.92, 1.72]) or violent (odds ratio = 1.17, 95% CI [0.76, 1.81]) recidivism. Nevertheless, having coded audio recordings of their sessions with POs allowed us to examine the association between specific PO behaviours and client recidivism.

To do this, PO behaviour was aggregated at the client level rather than the PO level. That is, all of a client’s recordings were aggregated to create mean scores for exposure to certain PO behaviours, including the proportion of each session spent discussing each criminogenic need and intervention techniques. Adding proportion of time spent discussing each criminogenic need to a hierarchical Cox regression model including group (R-Baseline vs. R-STICS), age, criminal history, and time offence free significantly improved prediction of recidivism (∆χ2 [5, N = 1,101] = 15.40, p = .009; see Table 7 for the final model estimates [estimates before the inclusion of proportions of criminogenic need discussions can be found in Appendix G]). Specifically, discussing procriminal attitudes/cognitions made a significant contribution to the prediction of recidivism, such that every 10% increase in the proportion of each session spent discussing procriminal attitudes/cognitions resulted in approximately a 5% decrease in recidivism. In contrast, a higher proportion of each session spent discussing substance abuse was associated with significantly higher recidivism rates, such that every 10% increase in the proportion of each session spent discussing substance abuse resulted in approximately a 4% increase in recidivism. None of the other discussion areas were independently associated with general recidivism. Additionally, none of the discussion areas were significantly associated with violent recidivism (see Appendix H).

| Model | HR | 95% CI | △ χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | 117.1 | 4 | < .001 | ||

| Covariates | |||||

| R-Baseline vs. R-STICSa | 1.24 | [0.996, 1.54] | |||

| Criminal history subscale (LSI-R) | 1.21 | [1.16, 1.26] | |||

| Age (year) | 0.98 | [0.97, 0.99] | |||

| Time offence-freeb (month) | 0.97 | [0.95, .997] | |||

| Step 2 | 15.40 | 5 | .009 | ||

| Discussion of criminogenic needsc | |||||

| Attitudes/cognitions | 0.95 | [0.91, 0.99] | |||

| Peers | 1.04 | [0.99, 1.08] | |||

| Family/marital | 1.01 | [0.97. 1.05] | |||

| Employment/education | 1.01 | [0.97, 1.05] | |||

| Substance abuse | 1.04 | [1.01, 1.07] | |||

Note. HR= hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (p < .05). ∆ χ2 indicates χ2 change from Step 1 to Step 2 (see Appendix G for model results with Step 1 variables only).

a Cox regression analysis was conducted based on the 281 R-Baseline and 820 R-STICS clients with data available for all model variables.

b Month(s) between the effective supervision start date and the first audio recording date for R-STICS clients.

c A unit of each variable is set to be .10 (i.e., 10%)

Like discussion content, adding quality of POs’ intervention skills to a hierarchical Cox regression model including group (R-Baseline vs. R-STICS), age, criminal history, and time offence free significantly improved prediction of general recidivism (△χ2 [df = 4) = 11.11, p = .025). However, after examining each intervention skill individually, only cognitive intervention skills made a significant contribution to the model (see Table 8, Model 1 for the contribution of cognitive intervention skills). Adding the other intervention skills (collaboration, structuring, and behavioural intervention skills) to a model already including cognitive intervention skills did not significantly improve the prediction of general recidivism (see Table 8, Model 2 for the full model results with all intervention skills). Additionally, their shared variance with cognitive intervention skills rendered the latter non-significant in Model 2. None of the intervention skills were significantly associated with violent recidivism (see Appendix I).

For cognitive interventions, Model 1 (Table 8) shows that, as the quality of the intervention improved, general recidivism rates significantly decreased. Examined differently, even when mere exposure to cognitive techniques was examined (regardless of quality), clients who were exposed to cognitive techniques were approximately 28% less likely to be reconvicted of a any new offence compared to clients who had not been exposed to cognitive techniques at all (hazard ratio = .72 [.58, .88]; see Appendix J for the survival curve by exposure to cognitive techniques). This ratio was constant over time (Wald χ2 = 3.30, p = .069). Additionally, the fixed 2-year general recidivism rate for clients exposed to cognitive techniques was 27.6%, while those not exposed to cognitive techniques had a general recidivism rate of 35.8% (odds ratios = 0.68 [0.51, 0.92]). Fixed 2-year violent recidivism rates did not significantly differ as a function of cognitive technique exposure (12.1% for those exposed to cognitive techniques vs. 10.4% for those not exposed to cognitive techniques; odds ratio = 1.18 [0.79, 1.75]) and the hazard ratio indicated no difference in survival curves controlling for varying follow-up times (hazard ratio = 1.03 [.76, 1.39]).

| Model | HR | 95% CI | △χ2 | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Cognitive Skills | |||||

| Step 1 | 117.1 | 4 | < .001 | ||

| Covariates | |||||

| R-Baseline vs. R-STICSa | 1.19 | [0.96, 1.48] | |||

| Criminal history subscale (LSI-R) | 1.21 | [1.16, 1.26] | |||

| Age (year) | 0.98 | [0.97, 0.99] | |||

| Time offence-freeb (month) | 0.97 | [0.95, 0.996] | |||

| Step 2 | 5.27 | 1 | .022 | ||

| Cognitive skills | 0.90 | [0.81, 0.99] | |||

| Model 2: All Intervention Skills | |||||

| Step 1 | 121.7 | 5 | < .001 | ||

| Covariates and Cognitive Intervention Skills | |||||

| R-Baseline vs. R-STICSa | 1.11 | [0.88, 1.40] | |||

| Criminal history subscale (LSI-R) | 1.21 | [1.16, 1.27] | |||

| Age (year) | 0.98 | [0.97, 0.99] | |||

| Time offence-freeb (month) | 0.97 | [0.95, 0.997] | |||

| Cognitive skills | 0.90 | [0.81, 1.01] | |||

| Step 2 | 5.84 | 3 | .120 | ||

| Other Intervention Skills | |||||

| Collaborative Skills | 1.07 | [0.98, 1.17] | |||

| Structuring skills | 1.13 | [0.98, 1.30] | |||

| Behaviour skills | 0.93 | [0.80, 1.09] | |||

Note. HR = hazard ratio. CI = confidence interval. Numbers in bold indicate statistical significance (i.e., p < .05). ∆χ2 indicates χ2 change from Step 1 to Step 2 (see Appendix G for model results with Step 1 variables only). Scores for each intervention skill were standardised (i.e., z-scores).

a Cox regression analysis was conducted based on the 280 R-Baseline and 822 R-STICS clients with data available for all model variables.

b Month(s) between the effective supervision start date and the first audio recording date for R-STICS clients.

Participation in Clinical Support Activities

Our original intention was to examine the extent to which POs participated in the ongoing clinical support activities and whether such participation improved PO behaviour toward their clients and eventually recidivism outcomes. Unfortunately, participation in these activities was not systematically collected at the beginning of the roll-out, and it was not until June 2013 that the province assumed collection of monthly meetings and refresher attendance and feedback on audio recordings. We examined the data from 2013 to 2018 and noted a number of unusual values that we could not explain. For example, there were 35 POs who did not attend a monthly meeting. Within a month of training, POs should have attended a meeting, and it is highly unlikely that so many did not because they left their position, were ill, or on vacation.

With the above noted caveat, we further explored the data and found no differences in discussion topics and skills between the POs with low participation and those with high participation. Based on the psychology of human learning, this made little sense; it is a law of human behaviour that practice and repetition improve behaviour (e.g., Bandura, 1969; Skinner, 1953). There is, however, a possible explanation. All POs were strongly expected to participate in clinical support activities, and it takes time for the new behaviours to solidify. We are missing the first two years of clinical support activities where we would have seen difficulties in applying STICS, and the later years reflect a plateau. This hypothesis is consistent with an exploratory analysis showing that clients who were supervised by POs with over 24 months of experience implementing STICS tended to have a lower 2-year recidivism rate than clients supervised by POs with less than 24 months of STICS experience (OR = 0.57 [0.29, 1.15] for general recidivism and OR = 0.27 [0.06, 1.14] for violent recidivism after controlling for age, LSI-R criminal history, and time offence-free before selection into the study). However, these differences were not statistically significant (see Appendix D for fixed 2-year recidivism rates as a function of PO experience).

Discussion

The implementation of STICS in BC community corrections had two intended outcomes. First, there was the expectation that PO behaviour would change and more closely align to RNR-based practices. Second, if this first outcome materialised, then client reconviction rates were expected to decrease with exposure to interventions from STICS-trained officers. Furthermore, the roll-out of STICS across the province not only afforded an opportunity to conceptually replicate earlier evaluations of the STICS model but also to learn how well STICS can be adopted on a larger scale.

PO Behaviour Change

As expected, PO behaviour showed significant improvements in accordance with the STICS model after training. First, after receiving STICS training, POs devoted a significantly greater proportion of the supervision sessions to criminogenic needs, with a corresponding decrease in time spent on noncriminogenic needs and conditions of probation. There is now strong evidence that targeting noncriminogenic needs without attention to criminogenic needs has almost no impact on reducing recidivism (Bonta, 2019; Bonta & Andrews, 2017; Gendreau et al., 2006; Lipsey & Cullen, 2007). There is also some research suggesting that increasing time spent on probation conditions is associated with increased recidivism (Bonta et al., 2008). Therefore, in STICS training, POs are encouraged to better balance their enforcement role with their “helper” role by keeping discussions of probation conditions to a minimum and staying focused on the clients’ criminogenic needs. Consistent with these training goals, POs in the current study were able to shift to a greater emphasis on criminogenic needs and spend less time on probation conditions and noncriminogenic needs.

Of particular interest was the significant increase in discussions of attitudes/cognitions. In STICS training, POs are taught that behind every criminogenic need is a problematic attitude or thought that may increase the risk for criminal behaviour. For example, having the attitude/cognition that “I deserve to get drunk on the weekend” or “Only suckers work for a living” can lead to behaviours that adversely affect prosocial outcomes. Therefore, the importance of addressing procriminal attitudes/cognitions is emphasized in STICS training, more so than other criminogenic needs. Following this training focus, the average proportion of each supervision session dealing with procriminal attitudes/cognitions increased substantially from pre- to post-training. Specifically, regardless of whether the client’s procriminal attitudes/cognitions were explicitly identified as a criminogenic need, discussion of attitudes/cognitions went from almost nonexistent prior to training (2% of each sessions’ segments on average) to being discussed in 18% of each sessions’ segments after training. This is consistent with earlier evaluations of the STICS model (Bonta et al., 2011, 2019), although the POs in the current study dedicated the largest proportion of each supervision session to discussing procriminal attitudes/cognitions (.18) compared to the 2011 (.13) and 2019 (.05) evaluations.

More time spent discussing procriminal attitudes necessarily leaves less time for discussions of other criminogenic needs. Indeed, substance abuse was discussed for a significantly smaller proportion of each session post-training and nonsignificant decreases were observed for the other criminogenic needs. In contrast, the 2011 evaluation (Bonta et al., 2011) showed no difference in substance abuse between the experimental and control conditions and reported significantly less attention to employment/education in the experimental condition (i.e., STICS-trained POs). Consistent with the current study, the 2019 evaluation (Bonta et al., 2019) found that STICS-trained POs spent a significantly lower proportion of each session discussing substance abuse compared to the control group. It also showed that STICS-trained POs spent a significantly lower proportion of each session discussing family/marital issues compared to the control group (Bonta et al., 2019). Thus, there are some inconsistencies in which criminogenic needs come to the fore after training from study to study. However, this may be partially explained by differences in proportion of time spent discussing procriminal attitudes/cognitions. Logically, if more time is spent discussing attitudes/cognitions, there will be less time to discuss other problematic areas. Furthermore, any discussion of attitudes/cognitions underlying the other criminogenic needs in this study was coded as procriminal attitudes/cognitions regardless of their content; therefore, it is possible that other criminogenic needs were still being discussed in the context of their underlying attitudes/cognitions. Unfortunately, the coding methodology was not sensitive to this nuance in conversations between the PO and his/her client.

Importantly, time spent on each criminogenic need was more balanced post-training, in contrast to pre-training sessions, which were skewed toward family/marital, employment/education, and substance abuse. This is an important shift as it indicates that more of the clients’ criminogenic needs are being addressed in supervision sessions, particularly procriminal attitudes/cognitions.