Evaluation of Public Safety Canada’s Roles in Support of DNA Analysis

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Profile

- 3. About the Evaluation

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations

- 7. Management Action Plan

- Annex A: Program Logic Model

- Annex B: Documents Reviewed

- Footnotes

Executive Summary

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of Public Safety Canada’s (PS) Roles in Support of DNA Analysis. DNA analysis is an important investigatory and prosecutorial tool used in the criminal justice system to quickly and precisely distinguish one individual from another. PS’ roles in supporting a national approach to DNA analysis consist primarily of three activities:

- Negotiate and administer contribution agreements with the provinces of Ontario and Quebec through the Biology Casework Analysis Program (BCACP) ($3.45M each per year) to support DNA analysis activities conducted in their forensic laboratories and to encourage their collaboration in submitting DNA profiles to the National DNA Data Bank (NDDB);

- Negotiate cost-sharing agreements (Biology Casework Analysis Arrangements, BCAAs) with each province and territory, excluding Ontario and Quebec, to partially recover costs required to process each jurisdictions’ crime scene DNA samples in RCMP laboratories and support the submission of crime scene DNA profiles to the NDDB; and

- Co-chair and provide secretariat services to the Federal/Provincial/Territorial (FPT) DNA Working Group, which is a consultation mechanism for DNA related issues and activities.

These activities are intended to support a sustainable national approach to DNA Analysis.

What we examined

The evaluation assessed the relevance, design, delivery, and performance of PS’ activities, including the extent to which these activities have been carried out efficiently and economically. Given that an important component of these activities is the administration of two contribution agreements, the evaluation also examined the extent to which the design, delivery and administration of these agreements conformed to the requirements of the Treasury Board (TB) Policy on Transfer Payments.

The evaluation covers the period from April 2013 to March 2018.

What we found

Relevance

PS’ roles and responsibilities are perceived by stakeholders to be important as PS is viewed to be in a good position to act as an intermediary between the RCMP as the service provider, and provinces/territories as service recipients to ensure that all jurisdictions have access to DNA analysis and that profiles from across the country are uploaded to the NDDB. The provision of these activities falls within the mandate of the Department and is consistent with its and the Government of Canada’s priorities of crime prevention, the provision of police services and improving the effectiveness of the administration of justice in Canada.

DNA analysis and the NDDB are still considered to be the most important prosecutorial and investigatory tools available to the criminal justice system. The demand for DNA analysis has been increasing at an unprecedented rate over the past five years due to the highly conclusive results provided through the analysis. In 2015-16 alone, RCMP forensic laboratories experienced a 25% increase in service requests in comparison to the year before.Footnote1 This increased demand underlines the need for further capacity building to meet these demands. In addition, there are new DNA applications that could potentially further facilitate police work and administration of justice, some of which have yet to be implemented in Canada.

Design and Delivery

PS activities have been delivered according to their original design, with program objectives and funding mechanisms remaining unchanged over the evaluation period.

The design and delivery of the contribution agreements, for the most part, conforms to the requirements of the TB Policy on Transfer Payments. However, reporting requirements, particularly the requirement for financial reporting, could be further streamlined. Furthermore, there was no evidence to indicate that performance information collected is being used to inform policy development and decision making beyond the issuing of payments.

The governance structure and membership, which includes an FPT Working Group, were found to be appropriate; however, the Working Group’s activities are largely focused on transactional matters despite the Terms of Reference listing the identification of “strategic priorities to optimize the use of DNA analysis for the criminal justice system” as one of the group’s objectives. Along these lines, there is a gap and absence of shared understanding around federal partner roles and responsibilities with respect to policy in support of DNA analysis.

There is also a difference of opinion between PS interviewees and other stakeholders on the state of PS’ relationship with and level of collaboration among FPT stakeholders. While attention has been given in recent years to improve this relationship, the majority of non-PS interviewees indicated that additional effort is required to increase collaboration between PS and key FPT stakeholders.

Performance: Effectiveness, Efficiency and Economy

PS activities have contributed to the achievement of their established objectives, including increased forensic laboratory capacity in Quebec and Ontario to conduct DNA analysis and an increased number of profiles submitted to the NDDB. The number of investigations assisted by the NDDB also increased by 47% during the period under review.

Although the allocated overhead cost for PS’ DNA analysis activities is low, the program faced a number of administrative challenges and inefficiencies during the period under review which increased the level of involvement that is normally required of PS program staff and internal services for a program of this nature.

Lack of dedicated program management experience/expertise; high staff turnover in both the program area and PS Center of Expertise for Grants and Contributions; and inconsistent record keeping and information management practices were identified as some of the internal challenges faced by the program. These challenges created administrative burdens for both the Department and the recipients, and caused delays in negotiations as well as administrative errors requiring extensions and amendments to signed contribution agreements.

Recommendations

The Assistant Deputy Minister of the Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch should:

- Clarify and formally communicate the role of Public Safety with respect to policy in support of DNA analysis.

- In consultation with FPT stakeholders, clarify the role of the DNA Working Group and ensure the DNA Working Group fulfills its objectives, as stated in its Terms of Reference.

- Work with Public Safety’s Grants and Contributions Centre of Expertise to implement sound and timely processes/practices for the administration of the Biology Casework Analysis Contribution Program (BCACP), including reporting requirements that are proportionate to the current risk profile, and documenting key decisions.

Management Action Plan

Management accepts all recommendations and will implement an action plan.

1. Introduction

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of Public Safety Canada’s Roles in Support of DNA Analysis. The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board of Canada (TB) Policy on Results and Policy on Transfer Payments and in compliance with section 42.1(1) of the Financial Administration Act. As the program includes grants and contributions with an annual average expenditure of above $5 million, the TB Policy on Results requires that the program be evaluated at least once every five years.

2. Profile

2.1 Background

Deoxyribonucleic acid – more commonly known as DNA - is an important investigatory and prosecutorial tool used in the criminal justice system to quickly and precisely distinguish one individual from another. The use of DNA analysis can shorten and focus police investigations, as well as help reduce prosecution and court costs, thereby enhancing public safety. DNA analysis also helps prevent the financial and social burdens of incarcerating innocent people, including the financial costs associated with the exoneration of wrongly convicted individuals.

The use of DNA for identification purposes in Canada is governed by the 1998 DNA Identification Act (the Act). Despite the fact that DNA analysis was being used throughout the criminal justice system in Canada since the late 1980s, there was no national coordination at that time to allow law enforcement agencies to take full advantage of the unfolding advances in DNA technology. The Act was legislated to formalize the use of DNA analysis, and to create a coordinated approach in its use in the administration of justice in Canada.

Under section 5 of this legislation, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness was made responsible for the establishment of a National DNA Data Bank (NDDB) to be maintained by the Commissioner of the RCMP.Footnote2 The main goals of the NDDB are to: “link crime scenes across jurisdictional lines, help identify or eliminate suspects, and determine whether a serial offender has been involved in certain crimes.”Footnote3

Once DNA samples are collected by police at crime scenes, they are analyzed in a forensic laboratory operated by either the Province of Ontario, the Province of Quebec, or the RCMP.Footnote4 The results of these analyses (called DNA profiles) are then entered into the NDDB. When all jurisdictions systematically submit DNA profiles into the NDDB there is an increased chance of finding a match, which in turn increases the effectiveness of the NDDB in supporting investigations or prosecutions.Footnote5

To support the effectiveness of the NDDB and the use of DNA analysis in the administration of justice in Canada, Public Safety Canada (PS) is primarily responsible for three activities:

- Negotiate and administer contribution agreements with the provinces of Ontario and Quebec through the Biology Casework Analysis Contribution Program (BCACP) to enhance their forensic laboratories’ capacity to conduct DNA analysis and secure their collaboration in uploading DNA profiles into the NDDB.

- Negotiate cost-sharing agreements (i.e., Biology Casework Analysis Agreements or BCAAs) with each province and territory, excluding Ontario and Quebec, to partially recover costs required for the RCMP National Forensic Laboratories to process each jurisdictions’ crime scene DNA samples, and support the submission of crime scene DNA profiles to the NDDB.

- Co-chair and provide secretariat services to the Federal Provincial Territorial (FPT) DNA Working Group, which is a consultation mechanism for DNA related issues and initiatives.

The responsibility and administration of these activities moved in 2017 from PS’ Serious and Organized Crime Policy Division to the Border Law Enforcement Strategies Division of the Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch. The resources allocated to administer these activities are outlined in Table 1.

| Fiscal Year | 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Salary (0.6 FTE)*Footnote6 |

$59,717 |

$59,717 |

$59,717 |

$59,717 |

$59,717 |

$298,585 |

O&MFootnote7 |

$4,207 |

$4,207 |

$4,207 |

$4,207 |

$4,207 |

$21,035 |

Total Internal Resources |

$63,924 |

$63,924 |

$63,924 |

$63,924 |

$63,924 |

$319,620 |

Contribution to ON |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$17,250,000 |

Contribution to QC |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$3,450,000 |

$17,250,000 |

Total Contribution |

$6,900,000 |

$6,900,000 |

$6,900,000 |

$6,900,000 |

$6,900,000 |

$34,500,000 |

Total Allocated Funding |

$6,963,924 |

$6,963,924 |

$6,963,924 |

$6,963,924 |

$6,963,924 |

$34,819,620 |

Source: PS Finance

*Employee Benefit Plan (EBP) (20%) and Accommodations included

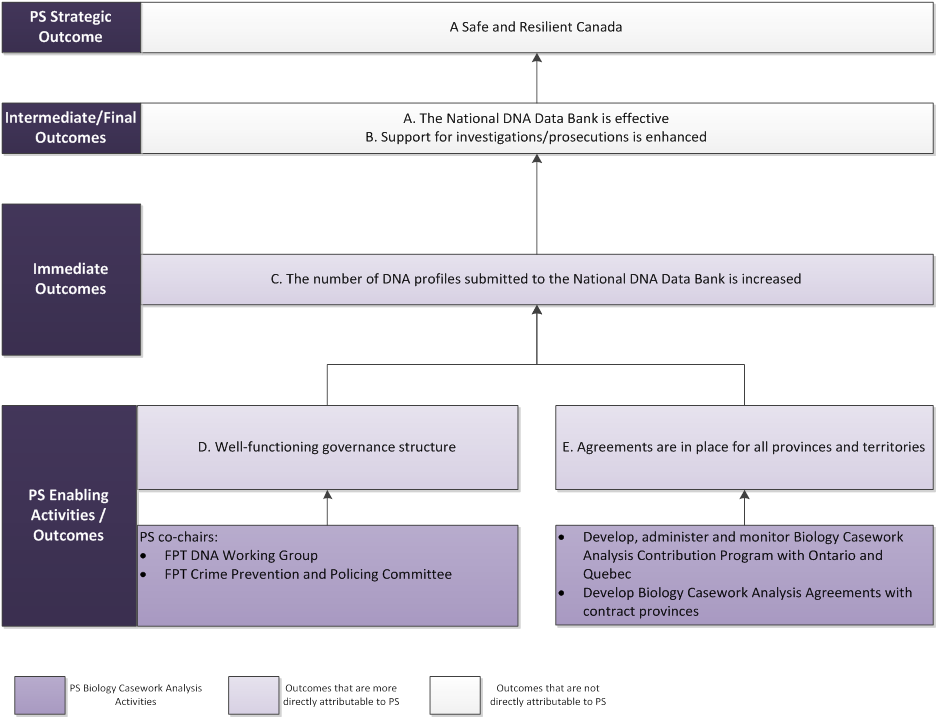

2.2 Logic Model

The logic model found in Annex A includes DNA analysis related activities undertaken by PS, and provides an overview of the linkages between the program’s activities, outputs and outcomes. PS’ activities are intended to contribute to the achievement of three levels of outcomes, including PS’ strategic outcome of A Safe and Resilient Canada. As indicated in the logic model, PS has direct influence and accountability for PS enabling activities and immediate program outcomes; however, it has limited influence over intermediate and final outcomes due to the fact that DNA analysis activities are a shared responsibility between various federal and provincial partners.

This program is included in the Performance Information Profile (PIP) for PS’ Border Policy Program that was developed in alignment with the requirements of the 2016 TB Policy on Results. The program PIP shares many elements with the program logic model (i.e., activities, outputs, outcomes). While the 2017-18 PIP was considered as part of the document review, the evaluation was based on the logic model and Performance Measurement Strategy that were in place during the time period under review.

3. About the Evaluation

3.1 Evaluation Objectives and Scope

The evaluation assessed the relevance and performance of PS’ DNA analysis activities from fiscal year 2013-14 to 2017-18, including the extent to which the design, delivery and administration of the program conformed to requirements outlined in the TB Policy on Transfer Payments, particularly sections 3.6 and 3.7.Footnote8 In assessing these issues, the evaluation explored potential alternative funding models, as well the incorporation of Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) considerations in the design, delivery and administration of the program.

This program was last evaluated in 2013-14, at which time recommendations were made to strengthen DNA analysis activities through increased focus on strategic issues and goals at the national level. The evaluation re-examined these issues to determine the extent to which the actions taken produced a stronger focus on broader strategic issues.

3.2 Methodology

3.2.1 Evaluation Core Issues

The evaluation examined both the design and delivery, as well as the relevance and achievement of program outcomes.

| Evaluation Topics | Areas Reviewed |

|---|---|

Relevance |

|

Design and Delivery |

|

Performance: Effectiveness |

|

Performance: Program Administration/Efficiency and Economy |

|

3.2.2 Lines of Evidence

Data collection for this evaluation included the following lines of evidence:

- Literature Review: Academic research and reports were reviewed to obtain insight into the continuing evolution of DNA analysis and to identify lessons learned and best practices with respect to DNA analysis policies and programs in like-minded countries that could inform the approach used by the Government of Canada.

- Document and Administrative Review: The document review included: past audit and evaluation reports, including the 2017-18 Evaluation of the RCMP’s Biology Casework Analysis; corporate, accountability and policy documents such as departmental performance reports and reports on plans and priorities; speeches from the Throne; etc.

- Review of Performance and Financial Information: The evaluation reviewed the Initiative’s performance data and analyzed available financial information to assess the efficiency and economy of PS DNA analysis activities’ cost management.

- Key Informant Interviews: Twenty (20) interviews were conducted with key informants from the following groups:

| Category | Number | Description |

|---|---|---|

Program Officials |

6 |

PS senior management and program staff (current and former) |

Other federal partners |

6 |

RCMP, Justice Canada, including their representatives on the FPT DNA Working Group |

PT DNA Working Group Members |

3 |

Provincial and Territorial members of the FPT DNA Working Group, including funding recipients |

PS Internal Services |

5 |

Legal, Finance, Centre of Expertise for Grants and Contributions |

3.3 Limitations

Performance and financial data were not readily available for some of the years under review. To mitigate this, existing data were used to extrapolate and interpolate. Available data were also supplemented with interviews and document review.

Although the members of the FPT DNA Working Group were invited to participate in the interview process, the majority of P/T stakeholders were not available for an interview. As such, participation was largely limited to federal partners. Document and file reviews, particularly a review of existing correspondence records between PS officials and the FPT DNA Working Group members were used to mitigate this limitation and to obtain insight into the Working Group members’ perspectives on relevant issues.

4. Findings

4.1 Relevance

Finding: There is a continued need for PS DNA analysis related activities, as DNA analysis and the NDDB play an imperative role in criminal investigations and the administration of justice. PS activities in support of this are consistent with government and departmental priorities, roles, and responsibilities.

4.1.1 Continued Need for PS Activities

To assess the extent to which there is a continued need for PS’ DNA analysis activities, the evaluation examined the importance of DNA analysis for police work and the administration of justice, as well as the stakeholders’ perception of how PS’ activities in this area ensure the continuation and advancement of such services in Canada.

A chronological review of the discovery and use of DNA analysis in police work indicates that it was first used in a criminal case in the United Kingdom in the investigation of the 1983 and 1986 rapes and murders of two British women, which resulted in exonerating the primary suspect and subsequently convicting the real perpetrator of these crimes.Footnote9 Over the years, the technology and techniques for conducting DNA analysis and extracting DNA profiles have been refined to become more efficient and accurate. The ability of law enforcement agencies to store DNA in national databases such as Canada’s NDDB has revolutionized forensic science and “has led to the arrest and prosecution of perpetrators of crimes who initially weren’t even considered suspects.”Footnote10 In Canada, the wrongful conviction and subsequent exoneration cases of David MilgaardFootnote11, Guy Paul MorinFootnote12 and several others using DNA analysis provided “powerful examples of how DNA evidence can be used to exonerate innocent people.”Footnote13,Footnote14 In fact, as outlined in Table 4, the NDDB has assisted almost 53,000 investigations since its inception.

| Offence | Total |

|---|---|

Murder |

3,479 |

Sexual assault |

5,795 |

Attempted murder |

1,031 |

Robbery (Armed) |

5,818 |

Break and Enter |

24,894 |

Assault |

4,161 |

Other |

7,675 |

Total |

52,853 |

Source: RCMP. Statistics for National DNA Data Bank issued September 30, 2018: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/nddb-bndg/stats-eng.htm

In recent years, the demand for DNA profiling services has increased. For example, in 2015-16 RCMP forensic laboratories experienced a 25% increase in service requests in comparison to the year before.Footnote15 The greatest increase was in crimes against property, which observed a 32% increase. Footnote16 Similarly, Ontario alone experienced a 118% increase in the number of cases received for processing at their forensic laboratory during the period under review.Footnote17 These increases are largely attributed to the highly conclusive results provided through DNA analysis, and signify the importance of and continued need for DNA analysis for police work and the administration of justice.

It should also be noted that DNA analysis is an evolving field. As demand increases, new applications that could potentially further facilitate police work and the administration of justice have been identified, but are yet to be implemented in Canada. For example, as technology continues to advance, researchers around the world are exploring possibilities for conducting faster DNA analysis,Footnote18 the use of familial DNA searching to assist in investigations,Footnote19 and how samples could provide additional information to support investigations, such as determining physical attributes of the donor (e.g., hair and eye colour),Footnote20 or producing a computerized 3D genome recreation of a suspect.Footnote21

Given this context, DNA analysis and the NDDB continue to be very important for police work. As Bob Paulson, the former Commissioner of the RCMP, has indicated “the National DNA Data Bank has become a vital investigative resource for law enforcement, helping to solve both recent and cold-case crimes.”Footnote22 The majority of the interviewees agreed with this sentiment and argued that PS plays a critical role in supporting DNA analysis activities across Canada, particularly through the negotiation of agreements with provincial/territorial jurisdictions to ensure continued collaboration in uploading profiles to the NDDB and that forensic laboratories have the capacity to meet increasing demands.

Considering PS’ roles and responsibilities with respect to negotiating the provision of policing services to contracting provinces and territoriesFootnote23 in general, these interviewees indicated that it is logical for PS to also be involved in the negotiation and administration contracts related to the provision of forensic services. PS is viewed by the majority of the interviewees as a neutral party that has been and can act as the intermediary between the RCMP (the service provider for the BCAAs) and provinces and territories (the service recipients for the BCAAs) to facilitate collaboration and to resolve issues and disagreements that can occur in such partnerships.

4.1.2 Consistency with Government and Departmental Roles and Responsibilities

Crime prevention and the administration of justice are areas of shared responsibility between the federal and provincial governments. While the power to establish criminal law and rules of investigation is exclusively granted to the federal Parliament under the Canadian constitution, provinces are responsible for administering justice in their jurisdictions, which includes organizing and maintaining the civil and criminal provincial courts and establishing civil procedure in those courts. That being said, criminal activities often extend beyond provincial and national borders. This necessitates the federal government’s involvement to coordinate national services in support of police investigations and criminal justice administration across the country.

Under the Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Act, S.C. 2005, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness is mandated to collaborate with federal partners, as well as other levels of government and other entities, on issues related to national and border security, crime prevention, community safety etc. Section 6(1)(c) of this Act authorizes the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness to make grants or contributions to support the mandate and priorities of the Department, and in support of an integrated approach to Canada’s safety and security.Footnote24 The use of DNA for identification purposes and the subsequent activities to establish a national DNA regime fall within this integrated approach and are governed by the 1998 DNA Identification Act.

In this context, the Department’s activities are consistent with the federal government’s roles and responsibilities, as these activities are intended to facilitate the government’s efforts to combat crime and establish an efficient criminal justice system.

4.1.3 Consistency with Government and Departmental Priorities

In his 2015 mandate letter to the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness, the Prime Minister reiterated the overarching responsibility of the Minister as leading the government’s work in ensuring that Canadians are safe.Footnote25 Similarly, the Minister of Justice was instructed in her 2015 mandate letter “to undertake modernization efforts to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the criminal justice system.”Footnote26 In addition, one of PS’ organizational priorities over the past few years has been to “increase the efficiency and effectiveness of crime prevention, policing and corrections, with a focus on at-risk and vulnerable populations, including Indigenous peoples, as well as those with mental health issues in the criminal justice system.”Footnote27

According to both the literature and interviewees, the use of DNA analysis can benefit the criminal justice system by contributing to the overall efficiency of the system. For example, by quickly identifying dangerous offenders, DNA analysis can help reduce prosecution and court costs. As such, the use of DNA evidence contributes to the achievement of the government’s priorities in the administration of justice and safety of Canadians.Footnote28 In doing so, prosecution and court costs are reduced, including the social and financial costs associated with the exoneration of wrongly convicted individuals.Footnote29

The majority of the interviewees have described PS’ efforts in developing and maintaining a nationally coordinated, cohesive DNA regime to be consistent with government and departmental priorities, as they contribute to the overall effectiveness and efficiency of the criminal justice system, as well as to the achievement of the Department of Public Safety’s strategic outcome of “A Safe and Resilient Canada.”

4.2 Design and Delivery

Finding: The program design and delivery, for the most part, conform to the requirements of the TB Policy on Transfer Payments. While the governance structure and membership were found to be appropriate, limited strategic direction was identified. Additionally, there is a gap and lack of shared understanding among federal partners with respect to responsibilities for policy in support of DNA analysis.

Upon the enactment of the DNA Identification Act in 2000, the federal government entered into funding agreements that provided slightly less than $2.3 million per year to both the government of Ontario and the government of Quebec.Footnote30 The main objectives of these contributions were to help these provinces offset the costs associated with DNA analysis, to build capacity in order to meet the growing demands, and to encourage collaboration in providing DNA profiles to the NDDB. The latter was perceived to be important as the success of the program was believed to depend on the number of profiles contained within the NDDB’s indices (i.e., the higher the number of profiles, the more effective the NDDB). The Biology Casework Analysis Contribution Program (BCACP) was established in 2010 as a result of a 2009 DNA Forensic Laboratory Services Cost and Capacity Review.Footnote31 Under this new program, the federal contribution amount to both Ontario and Quebec increased to $3.45 million per year,Footnote32 and responsibility for the administration of the agreements transferred from the RCMP to PS.

Around the same time, the federal government entered into cost-sharing agreements with the other provinces and territories (BCAAs). Although the agreements have gone through several iterations, the current agreements were signed in 2014 for a period of 10 years. Under these agreements, the contracting provinces and territories compensate the federal government 54% of the baseline cost of the forensic crime scene analysis provided to them by the RCMP laboratories. The amount paid is based on each province and territories’ proportional usage. “The baseline for recovery is to be recalculated every two years, using actual costs from the previous two years.”Footnote33 While PS is responsible for negotiating both agreements, the RCMP administers the BCAAs with the contracting provinces and territories.

During the period under review, the program design and delivery, including its main premise have remained relatively unchanged. In assessing the extent to which this design and delivery is still appropriate, the evaluation examined its governance structure, clarity of roles and responsibilities, conformity with the TB Policy on Transfer Payments, as well as relevant GBA+ considerations.

4.2.1 Governance

The program’s governance structure consists of a FPT Assistant Deputy Minister-level committee, the Crime Prevention and Policing Committee (CPPC); and the Federal Provincial/Territorial DNA Working Group (FPT DNA WG). Reporting to the FPT Deputy Ministers Responsible for Justice and Public Safety, the CPPC is mandated “to proactively identify, examine, and discuss crime prevention and policing policy issues within and across jurisdictions.”Footnote34 The CPPC is authorized “to create standing committees, items, or working groups in order to advance joint work on specific issues.”Footnote35 The FPT DNA Working Group is one such group that has been established “to provide national recommendations to the CPPC regarding long-term sustainability of DNA analysis in Canada.”Footnote36 As such, the Working Group’s objectives are:

- Reporting to the CPPC regarding service delivery and ongoing costs related to the Biology Casework Analysis Agreements;

- Identifying strategic priorities to optimize the use of DNA analysis for the criminal justice system; and

- Collaborating and acting as a consultation mechanism for DNA related initiatives.Footnote37

The Working Group’s membership consists of representatives from Public Safety, the RCMP, Justice Canada, and at least one representative from each province and territory. The Working Group’s membership mirrors that of the CPPC, and both groups are co-chaired by PS and a P/T representative on a rotational basis.Footnote38 Terms of Reference have been developed for both groups that clearly outline each committee’s respective roles, responsibilities and reporting structure.Footnote39

The governance structure, including its membership composition and the level of oversight provided were perceived by the majority of interviewees to be appropriate. However, based on interviews and a review of program documentation, the Working Group’s activities have largely focused on transactional matters related to the negotiation and administration of cost-sharing agreements between the RCMP and the contract provinces and territories, with limited attention given to strategic priorities. It is important to note that when the program was last evaluated in 2013-14, certain weaknesses in the mandate of the Working Group, as well as a similar lack of strategic direction in both the Working Group and PS’ activities were identified in the evaluation report.Footnote40 To address this gap, the evaluation report contained two recommendations: that PS lead the development of a strategic plan that would outline policy goals to fully optimize the use of DNA for the Canadian criminal justice system; and that the Working Group’s Terms of Reference be renewed to reflect a stronger focus on strategic issues.

In response to these recommendations, the Working Group’s Terms of Reference were updated to add “[i]dentifying strategic priorities to optimize the use of DNA analysis for the criminal justice system” as one of its objectives, and a strategic plan was drafted. While efforts were made to share the strategic plan with members of the Working Group, the evaluation team did not find any evidence to indicate that the plan was ever implemented. In fact, there was a lack of awareness among interviewees about the existence of a strategic plan or the rationale for its development. Some of the interviewees have attributed this to the fact that strategic issues are usually discussed as part of negotiations and suggested the focus of the Working Group should remain transactional. However, others identified this to be a missed opportunity for using the collective expertise of the Working Group to explore policy and social implications of wider applications of DNA analysis activities, and to formalize the desired overarching DNA program across Canada.

Document review and interviews indicated that PS’ relationship with, and the level of collaboration among, FPT stakeholders has somewhat improved in recent years. Having said that, certain PS administrative practices for the BCACP that occurred during the period under review negatively impacted the Department’s relationships with some of its partners. Particular attention has been given in recent years to address these issues and to foster an improved relationship with all stakeholders; however, multiple interviewees indicated that more effort is needed to increase the level of collaboration between PS and key FPT stakeholders.

4.2.1.1 Clarity of Roles and Responsibilities

Through a review of available documents, the evaluation identified a gap with respect to the delineation of responsibility between federal partners for policy research, advice and development. The difference of opinion expressed by certain PS interviewees vis-à-vis other federal partners highlighted a lack of shared understanding regarding where the responsibility for this role lies.

The provision of “well-informed policy advice and policy development” was included as one of PS’ enabling activities/outcomes in the version of program’s logic model that was in place during the 2013-14 evaluation. Furthermore, the National Biology Casework Strategic Plan that was developed subsequent to the 2013-14 evaluation stated that “Public Safety, with the support of other federal departments such as Justice Canada provides leadership through the coordination and development of advice, policy recommendations, governance, and research activities that support DNA analysis.”Footnote41 However, the program’s most recent logic model (Annex A) does not include any reference to Public Safety’s role in policy development, research, or advice. Nor did program documentation or interviewees identify policy and research work as a key activity conducted over the period covered by this evaluation. Given this, the evaluation sought the perspectives of the interviewees on the issue and its implication for the program.

Interviewee perceptions varied and it remains unclear if this responsibility should fall under PS or the RCMP. Considering that the use of DNA analysis in police work and administration of justice is an evolving field, the evaluation underlines the importance of this work being supported by a strong policy research and policy development capacity. To facilitate the development of such capacity, it is important that the roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of different stakeholders, including those of the PS, be clarified and documented at the appropriate levels to address any policy gaps and ensure a whole of government perspective.

4.2.2 Conformity with TB Policy on Transfer Payments

The evaluation assessed the extent to which the design, delivery and administration of the Contribution Agreements (BCACP) conformed to the requirements outlined in the TB Policy on Transfer Payments, in particular sections 3.6 and 3.7. These sections require that transfer payments be managed in a manner that is sensitive to risks, strikes an appropriate balance between control and flexibility, and establishes the right combination of good management practices, streamlined administration and clear requirements for performance.

For the most part, interviewees agreed that the design, delivery and administration of the contribution program conformed to the requirements of the TB Policy on Transfer Payments. For example, the program is based on multi-year funding agreements; it has been risk assessed and the risk level has been determined to be low; it has also established, to some extent, a clear requirement for performance reporting. Yet, there are opportunities for improvement on the issue of striking an appropriate balance between control and flexibility, particularly with respect to the issue of financial reporting. Document review and the majority of the interviewees highlighted this to have been a source of contention between the Department and the funding recipients (i.e., Ontario and Quebec). This is primarily because the recipients do not collect financial information on a basis that would allow them to easily feed into the required reports. Furthermore, the purpose and value-added of such reporting was questioned by some of the interviewees. The majority of the interviewees involved in the administration of these contribution agreements also acknowledged this as a problem and indicated that, aside from complying with certain template requirements, there is no operational need for imposing requirements such as quarterly financial reporting. Internal PS confusion over requirements for reporting emerged as a trend over the period under review, which, according to interviewees, caused increased back-and-forth and administrative burden on the recipient.

Considering the program’s low level of risk, as determined through its risk assessment, the consistent nature and problem-free track records of the funding recipients, the type of service that these funding recipients are providing, and the flexibility granted under section 6.5.7 of the TB Policy on Transfer Payments,Footnote42 it would be prudent for the Department to reassess and clarify the type and quantity of financial information that it requires from funding recipients. This is to ensure that the reporting requirements are not burdensome for the funding recipient, but are proportionate to the level of risk and necessary for accountability and program management purposes.

While the mechanisms used to collect performance information are in place and perceived to be appropriate, the evaluation was unable to confirm if the performance information collected is being used by the Department for all intended purposes. Currently, the Department requires the recipients to submit copies of financial budgets, including current and/or future year’s anticipated budgets, as well as the annual program activity reports on the previous year’s accomplishments. These reports are meant to be used for both accountability purposes (i.e., as the basis for issuing the contribution payments) as well as to be reviewed by the program to monitor the recipients’ relevant activities. Findings from interviews and document reviews indicate that these performance reports are only being used for the purpose of issuing the payments. To build on the performance information gathered from recipients, the Department may wish to consider conducting a year-to year comparison of the information to monitor these activities, establish trends and provide a feedback loop to recipients to inform decision making.

4.2.3 GBA+ Considerations

At the time of the program’s establishment in 2010, the Department conducted a preliminary gender-based analysis assessment. The analysis did not identify any overarching gender-based implications, due in large part to the anonymization of DNA profiles during analysis.Footnote43 However, some unintended gendered impacts were highlighted as part of that initial analysis. For example, DNA evidence is often used to investigate particular types of violent crimes, which have gendered differences, both in terms of perpetrators and victims. DNA evidence is also used to prosecute and convict sex offenders. Recent statistics confirm that women and girls continue to be over-represented among victims and survivors of reported sexual assault and ‘other sexual violations.’Footnote44

In addition, some interviewees highlighted the importance of the newly established humanitarian indices (i.e., Missing Persons Index, Relatives of Missing Person Index and Human Remains Index) to facilitate the work of the National Inquiry on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. According to these interviewees, there is a connection between the national inquiry and ensuring that police services are providing adequate analysis, due to the gendered nature of these crimes.

The program may also benefit groups who experience higher rates of wrongful convictions by accurately identifying the correct perpetrator, and reducing the number of wrongful convictions across the country. In the United States, people of colour represent the majority (61%) of all DNA exonerations to date.Footnote45 While the evaluation could not obtain disaggregated statistics regarding instances of wrongfully convicted individuals across Canada, available statistics do show that Indigenous people and other visible minorities are overrepresented in both federal and provincial correctional institutions.Footnote46

While the program has some gender and diversity implications, evidence of considerations for how the program may impact the broader context of the criminal justice system was not documented. Under the Government’s renewed commitment to GBA+, these and other considerations should be taken into account throughout program implementation and monitoring to ensure the program remains inclusive.

4.3 Performance – Effectiveness

Finding: The Ontario laboratory’s capacity to conduct DNA analysis has increased, while Quebec’s has remained relatively consistent. The number of DNA profiles contained in the NDDB has steadily increased since its inception in 2000, and the number of investigations assisted by the NDDB increased by 47% during the period under review.

The program logic model identifies ‘a well-functioning governance structure’ and ‘agreements with all provinces and territories’ as PS enabling activities and outcomes that seek to contribute to the immediate outcome of an increased number of DNA profiles submitted to the NDDB. Agreements are currently in place with all provinces and territories. As outlined in section 4.2.1 of this report, the state of the current governance structure was found to be appropriate. To assess the extent to which these activities have contributed to the achievement of the immediate outcome, the evaluation reviewed performance information provided by Ontario and Quebec, as well as data from the NDDB. Trends were established to determine if capacity in Ontario and Quebec’s provincial forensic laboratories has increased as a result of this program, as well as if the number of submissions and use of the NDDB increased over the period under review.

4.3.1 Capacity of Provincial Forensic Laboratories to Conduct DNA Analysis

According to performance data submitted by the provinces, the capacity of Ontario’s Centre of Forensic Sciences has increased, as evidenced by a consistent increase in the total number of cases processed each year during the period under review (Table 5). During the same period, the number of cases completed by Quebec’s Laboratoire de sciences judiciaires et de médecine légale decreased between 2015-16 and 2016-17, then increased slightly in 2017-18. These patterns suggest that Quebec’s capacity has been maintained.

| 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ontario |

6,207 |

6,659 |

7,425 |

8,288 |

9,003 |

7,516 |

QuebecFootnote47 |

- |

- |

4,966 |

4,514 |

4,627 |

4,702 |

Source: Performance Reports provided by Ontario and Quebec

The number of cases received for processing also increased each year for both provinces, which reflects the increased demand for DNA analysis throughout the criminal justice system and underlines the need for further capacity building to meet these demands. Over the period under review, Ontario experienced an increase of 118% in the number of cases received for processing.

Performance data also show that Ontario's processing times have decreased since 2013-14, but not in a consistent manner. After a significant decrease between 2013-14 and 2014-15, the average turnaround time remained the same or increased each year since. For Quebec, processing times remained consistent between 2015-16 and 2016-17, but significantly increased in 2017-18. Despite this, both provinces submitted either a consistent or increased number of DNA profiles to the Crime Scene Index (CSI) of the NDDB each year during the period under review, with Ontario increasing their number of submissions by 70% since 2013-14. As outlined in Table 6, Quebec submitted an average of 2,651 profiles annually, while Ontario submitted an average of 4,580 profiles annually. The discrepancy between the number of cases processed in forensic laboratories and the number of profiles submitted to the CSI of the NDDB can be attributed to multiple factors, including duplicate samples, rejected samples that did not generate a DNA profile, and the criteria that only DNA profiles derived from a designated offence can be added to the CSI.Footnote48

| 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | Average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Ontario |

3,506 |

3,715 |

4,385 |

5,333 |

5,958 |

4,580 |

QuebecFootnote49 |

- |

- |

2,791 |

2,436 |

2,727 |

2,651 |

Source: Performance Reports provided by Ontario and Quebec

From 2013-14 to 2017-18, PS funding covered an annual average of approximately 30% and 43% of Ontario and Quebec’s forensic laboratories DNA analysis expenses, respectively, according to financial information provided by the recipients. This is in comparison to the 46% of costs covered for other provinces and territories under BCAA cost-sharing agreements. It should be noted that BCAAs are designed in a way to respond to fluctuations in demand for the service, while funding for Ontario and Quebec remains the same regardless of the number of DNA samples processed. Funding levels for Ontario and Quebec have not changed since 2010.

4.3.2 Use of the DNA National Data Bank to Support Criminal Investigations

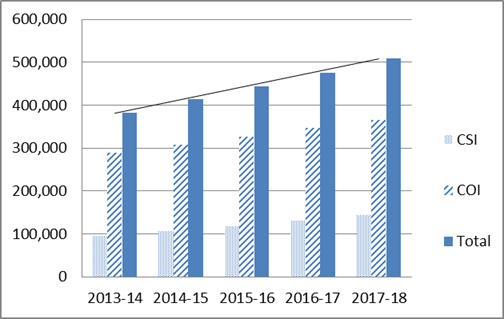

Overall, the number of DNA profiles contained in the NDDB has steadily increased since its inception in 2000. According to RCMP reports, an average of around 35,000 profiles were added annually to the databank over the period covered by this evaluation. Based on the statistics provided in the RCMP’s Annual Reports on the National DNA Data Bank, the databank contained 526,607 profiles as of September 2018.Footnote50 Of these, 375,282 profiles were within the Convicted Offender Index (COI) and 151,325 were in the Crime Scene Index (CSI). Figure 1 outlines this total increase, as well as the breakdown of profiles contained in the CSI and COI over the past five years.

Figure 1 - Number of DNA Profiles Contained in the National DNA Databank

Image Description

The graph represents the number of DNA profiles contained in NDDB by year from 2013-14 to 2017-18. These numbers are further broken down to show the number of profiles housed within the Crime Scene Index (CSI) and Convicted Offender Index (COI) of the NDDB for the period under review. The total number of profiles has increased consistently each year for both indices. Overall, the total number of DNA profiles contained in the National DNA Databank has increased from 382,906 in 2013-14 to 509,528 in 2017-18.

Sources: The National Data Bank of Canada Annual Reports (2013-14 to 2017-18)

Of the 151,325 profiles in the CSI, the majority were submitted by Ontario’s Centre of Forensic Sciences in Toronto (56,713), followed by the RCMP forensic laboratories (51,354), and Quebec’s Laboratoire de sciences judiciaires et de médecine légale in Montreal (43,258).Footnote51

With this increase in profiles, a total of 55,275 investigations have been assisted by the NDDB since its creation in June, 2000.Footnote52 The number of new investigations assisted each year by the NDDB is outlined in Table 7 and represents an increase of 47% over the past five years.

| 2013-14 | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Number of Investigations Assisted by the NDDB |

3,921 |

4,796 |

5,622 |

5,508 |

5,751 |

Source: The National DNA Databank of Canada Annual Report 2017-18

The number of offender and forensic hits has also increased each year, with a 47% and 44% increase in hits from 2013-14 to 2017-18, respectively. These hits are important matches made to inform investigations and prosecutions by linking cases and identifying offenders. Offender hits refer to matches made between a crime scene DNA profile and a convicted offender DNA profile, while forensic hits refer to matches made between different crime scene DNA profiles. These trends suggest that the program has been effective in contributing towards its intended outcomes.

4.3 Performance – Program Administration/Efficiency and Economy

Finding: Overall, program administration has been rife with challenges and problems, including a lack of dedicated program management experience/expertise, high staff turnover, and inconsistent record keeping and information management practices. Payments to Ontario and Quebec were largely made in a timely manner; however, delays in negotiations and PS administrative errors required extensions and amendments to signed agreements.

Document review indicates that payments have been largely made in a timely manner and in accordance with the established payment schedule. However, concerns were raised by interviewees regarding the timeliness of negotiations and the renewal of contribution agreements with Ontario and Quebec. Five year contribution agreements with both Ontario and Quebec were signed in 2010-11 which covered the period of 2010-11 to 2014-15. A review of program documentation revealed PS administrative delays in renegotiating these agreements in 2014-15, and concerns were raised by recipients regarding the late provision of draft agreements. Insufficient time was provided for the recipient’s own review and approval and one-year extensions were required for 2015-16.

Four-year agreements were signed with both provinces for 2016-17 to 2019-20; however, due to further delays in negotiation and PS administrative omissions, both agreements contained errors which required multiple amendments to address missing information.

Multiple interviewees voiced that this should be a straightforward contribution program, as it is an established, low risk program with consistent payments each year. While program activities have in large part been managed with limited resources,Footnote53 substantial administrative attention for a program of this size and risk level has been required over the past five years.

All internal PS interviewees highlighted and attributed some of the administrative challenges to a lack of dedicated program officers for the administration of the contribution agreements, compounded by the program being situated in a policy area, rather than with experienced program administrators. According to interviewees, this lack of experience and expertise placed a burden on program staff, the PS Grants and Contributions (G&Cs) Centre of Expertise, and on the recipients due to increased back-and-forth communication. In some cases, this resulted in a lack of consistency and administrative errors. These findings align with the 2017 Public Safety Internal Audit of Grants and Contributions, which found that “the varied expertise of administrators of G&Cs programs dispersed across the department has contributed to the lack of consistency of G&Cs administration in terms of role and responsibilities.”Footnote54 At the time of this evaluation, discussions were ongoing in the Department as to how to address the audit finding and subsequent recommendation to reorganize the administration of G&Cs across PS.

High staff turnover in both the program area and the Centre of Expertise during the period under review, as well as the 2017 transfer of program responsibilities from the Serious and Organized Crime Policy Division to the Border Law Enforcement Strategies Division further contributed to the challenge of retaining corporate knowledge and program expertise. Inconsistent record keeping and information management practices also emerged as an area of concern throughout the course of the evaluation.

Some progress has been made in the past year to better align the management of this program with departmental Gs&Cs processes, and to improve the efficiency of the program. Specifically, the process for reporting to provinces and territories for BCAAs has been simplified, with the RCMP now providing these reports directly to provinces and territories, rather than through PS.Footnote55 These reports are developed by the RCMP to inform each province with statistics of analysis conducted on their behalf, and the amount owed as a result of the cost-sharing agreement. By removing PS from the process, reports are being provided to each province and territory in a more efficient manner.

Lastly, interviewee perceptions on the appropriateness of the funding mechanism varied. While a small majority of interviewees indicated that the existing mechanisms were appropriate, some thought a grant would be more suitable than a contribution agreement (that is for BCACP) as it is a stable funding, low risk program with provincial partners, and a grant could reduce the administrative burden on both the recipient and PS. Others expressed that the cost-sharing agreements (BCAAs) could be integrated into existing Policing Service Agreements held between the RCMP and provinces and territories to improve program efficiency and service delivery.

5. Conclusions

This evaluation assessed the relevance (i.e., continued need), design, delivery and performance (achievement of its objectives) of PS’ roles in support of DNA analysis activities over the past five years. The evaluation concluded that there is a continued need for PS’ activities in this area as DNA analysis continues to be a very important investigatory tool for the criminal justice system. In addition, the demand for such analysis is increasing and the technology is evolving, which underlines the need to continue building capacity to meet these demands.

In terms of design and delivery, the program was delivered in accordance to its original design. Program objectives and the funding mechanisms used remain unchanged. The governance structure and membership were found to be appropriate. However, the evaluation identified a lack of shared understanding with respect to federal partner roles and responsibilities for DNA related policy research, policy development, and policy advice, as well as a lack of strategic focus in the FPT DNA Working Group activities. This lack of strategic focus does not align with the objectives stated in the Working Group’s Terms of Reference.

Although the design and delivery of the contribution component of the program (BCACP) for the most part conformed to the requirements of the TB Policy on Transfer Payments, the evaluation identified the need to streamline reporting requirements from the funding recipients and better utilize the performance information collected. A preliminary GBA+ assessment was completed at the time of the program’s establishment. Given the Government’s priority of ensuring all programming is inclusive, a full GBA+ analysis will need to be completed as part of any program renewal process, and monitoring of GBA+ considerations should continue throughout implementation.

PS activities contributed to the achievement of their established objectives, including increased forensic laboratory capacity in Quebec and Ontario to conduct DNA analysis and an increased number of profiles submitted to the NDDB. The number of investigations assisted by the NDDB also increased consistently during the period under review.

The evaluation highlighted a number of administrative challenges and inefficiencies that PS faced in carrying out its activities. Interviewees attributed these internal capacity challenges primarily to a lack of dedicated program management experience/expertise, high staff turnover in both the program area and the PS Gs&Cs Center of Expertise, and inconsistent record keeping and information management practices. Although these could be considered as some of the factors contributing to the administrative challenges faced by the Department, the importance of promoting and sustaining familiarity with the specifics of the program, including its history, terms and conditions, and the context in which the program operates should also be recognized.

In light of these findings, the evaluation has identified opportunities for improvement that are presented below in the spirit of continuous improvement.

6. Recommendations

The Assistant Deputy Minister of the Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch should:

- Clarify and formally communicate the role of Public Safety with respect to policy in support of DNA analysis.

- In consultation with FPT stakeholders, clarify the role of the DNA Working Group and ensure the DNA Working Group fulfills its objectives, as stated in its Terms of Reference.

- Work with Public Safety’s Grants and Contributions Centre of Expertise to implement sound and timely processes/practices for the administration of the Biology Casework Analysis Contribution Program (BCACP), including reporting requirements that are proportionate to the current risk profile, and documenting key decisions.

7. Management Action Plan

| Recommendation | Action Planned | Planned Completion Date |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Clarify and formally communicate the role of Public Safety with respect to policy in support of DNA analysis. | In consultation with federal partners, develop a roles and responsibilities chart that will be approved by senior federal officials and shared with PT partners. |

March 2020 |

| 2. In consultation with FPT stakeholders, clarify the role of the DNA Working Group and ensure the DNA Working Group fulfills its objectives, as stated in its Terms of Reference. | Public Safety will consult with FPT stakeholders to clarify the role of the DNA Working Group and ensure that it is accurately reflected in its Terms of Reference. |

March 2020 |

| 3. Work with Public Safety’s Grants and Contributions Centre of Expertise to implement sound and timely processes/practices for the administration of the BCACP, including reporting requirements that are proportionate to the current risk profile, and documenting key decisions. | The Comptrollers Directorate is in the process of revising the G&Cs administration process framework related to PS programs. This enhanced framework will include updated PS G&Cs directives, procedures, training, tools and templates to ensure sound and timely processes/practices for the administration of PS G&C programs, including the BCACP. |

March 2020 |

PS will review and, where necessary, revise BCACP Terms and Conditions to support leaner and streamlined reporting requirements. The administration of the BCACPs is scheduled to move to EMPB in 2020. The program area, in consultation with EMPB, will develop and implement information management practices to ensure a smooth transition of files. |

March 2021 |

Annex A: Program Logic Model

Image Description

Public Safety Canada’s Enabling Activities/Outcomes are:

- Outcome E. Agreements are in place for all provinces and territories (Develop, administer and monitor Biology Casework Analysis Contribution Program with Ontario and Quebec; Develop Biology Casework Analysis Agreements with contract provinces).

- Outcome D. Well-functioning governance structure (PS co-chairs the FPT DNA Working Group and the FPT Crime Prevention and Policing Committee).

These activities/outcome lead to the Immediate Outcome of:

- Outcome C. The number of DNA profiles submitted to the National DNA Data Bank is increased.

The immediate outcome leads to the following Intermediate Outcomes/Final Outcomes:

- Outcome B. Support for the investigations/prosecutions is enhanced.

- Outcome A. The National DNA Data Bank is effective.

The intermediate outcomes lead to Public Safety’s Strategic Outcome of:

- A Safe and Resilient Canada.

Outcomes C, D, and E are outcomes that are more directly attributable to PS.

Outcomes A, B, and the PS Strategic Outcome are outcomes that are not directly attributable to PS.

Annex B: Documents Reviewed

Ang, J. (2016). Advances in Portable DNA Analysis Bring us Closer to a Future with Medical Tricorders. Retrieved from: https://phys.org/news/2016-07-advances-portable-dna-analysis-closer.html.

Beattie, K., Boudreau, V., & Raguparan, M. (2013). Representation of Visible Minorities in the Canadian Criminal Justice System. Department of Justice Canada. Retrieved from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2018/jus/J4-54-2013-eng.pdf.

Butler, J.M. (2015). The Future of DNA Analysis. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 370: 20140252. Retrieved from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0252.

Canada (1998). DNA Identification Act. Retrieved from: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/d-3.8/.

Canada Gazette (October 14, 2017). Regulation Amending the DNA Identification Regulations, 151(41). Retrieved from: http://www.gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2017/2017-10-14/html/reg2-eng.html.

CBC News (2008). Indepth: David Milgaard – Timeline. Retrieved from: https://www.cbc.ca/news2/background/milgaard/.

Deakin University (2017). How DNA analysis has revolutionized criminal justice: Dr. Annalisa Durdle. Retrieved from: http://this.deakin.edu.au/career/how-dna-analysis-has-revolutionised-criminal-justice.

Government Consulting Services, Public Workings and Government Services (2009). DNA Forensic Laboratory Services Cost and Capacity Review. Final Report, February 18, 2009.

Government of Canada. Department of Justice Canada (2004). Report on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice: FPT Heads of Prosecutions Committee Working Group. Retrieved from: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/ccr-rc/pmj-pej/index.html.

Government of Canada. Department of Justice Canada (2017). JustFacts: Indigenous overrepresentation in the criminal justice system. January 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/jr/jf-pf/2017/jan02.html.

Government of Canada. Office of the Prime Minister (2015). Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Mandate Letter, November 12, 2015. Retrieved from: https://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister-justice-and-attorney-general-canada-mandate-letter.

Government of Canada. Office of the Prime Minister (2015). Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Mandate Letter, November 12, 2015. Retrieved from: https://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister-public-safety-and-emergency-preparedness-mandate-letter.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2013). 2013-14 Report on Plans and Priorities. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rprt-plns-prrts-2013-14/index-en.aspx.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2014). 2013-14 Departmental Performance Report. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-prfrmnc-rprt-2013-14/dprtmntl-prfrmnc-rprt-2013-14-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2014). 2013-2014 Evaluation of the Biology Casework Analysis Activities. Final Report. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/vltn-blgy-cswrk-nlyss-2013-14/index-en.aspx.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2014). 2014-15 Report on Plans and Priorities. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rprt-plns-prrts-2014-15/index-en.aspx.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2015). 2014-15 Departmental Performance Report. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-prfrmnc-rprt-2014-15/dprtmntl-prfrmnc-rprt-2014-15-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2015). 2015-16 Report on Plans and Priorities. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rprt-plns-prrts-2015-16/rprt-plns-prrts-2015-16-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2016). 2015-16 Departmental Performance Report. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-prfrmnc-rprt-2015-16/dprtmntl-prfrmnc-rprt-2015-16-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2016). 2016-17 Report on Plans and Priorities. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/rprt-plns-prrts-2016-17/rprt-plns-prrts-2016-17-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2016). Internal Audit of Grants and Contributions: Audit Report. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/ntrnl-dt-grnts-cntrbtns-2017/index-en.aspx.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2017). 2017-18 Departmental Plan. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-pln-2017-18/dprtmntl-pln-2017-18-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2017). 2016-17 Departmental Results Report. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-rslts-rprt-2016-17/dprtmntl-rslts-rprt-2016-17-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2018). 2018-19 Departmental Plan. Retrieved from: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/dprtmntl-pln-2018-19/dprtmntl-pln-2018-19-en.pdf.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2012). National Police Services: Building a Sustainable Future. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/national-police-services-building-a-sustainable-future.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2014). National DNA Data Bank Advisory Committee 2013-2014 Annual Report. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/dnaac-adncc/annurp/2013-2014-annurp-eng.htm.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2014). National DNA Data Bank of Canada – Annual Report 2013-2014 – DNA: then and now. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/pubs/nddb-bndg/ann-13-14/index-eng.htm.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2015). National DNA Data Bank Advisory Committee 2014-2015 Annual Report. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/dnaac-adncc/annurp/2014-2015-annurp-eng.htm.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2015). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2014-2015. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/the-national-dna-data-bank-canada-annual-report-2014-2015.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2016). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2015-2016. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/the-national-dna-data-bank-canada-annual-report-2015-2016.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2017). Evaluation of the RCMP’s Biology Casework Analysis. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/evaluation-the-rcmps-biology-casework-analysis.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2017). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2016-2017. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/en/the-national-dna-data-bank-canada-annual-report-2016-2017.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2018). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2017-2018.

Government of Canada. Royal Canadian Mounted Police (2018). Statistics for National DNA Data Bank. Issued September 30, 2018. Retrieved from: http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/nddb-bndg/stats-eng.htm.

Government of Canada. Statistics Canada (2017). Women in Canada: A Gender-Based Statistical Report. Women and the Criminal Justice System. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-503-x/2015001/article/14785-eng.htm.

Government of Canada. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2012). Directive on Transfer Payments. Retrieved from: https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=14208.

Government of Canada. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2012). Policy on Transfer Payments. Retrieved from: https://www.tbs-sct.gc.ca/pol/doc-eng.aspx?id=13525.

Governor General (2011). Speech from the Throne to open the First Session of the Forty First Parliament of Canada. June 3, 2011. Retrieved from: https://lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/Parliament/procedure/throneSpeech/speech411.

Governor General (2013). Speech from the Throne to open the Second Session Forty First Parliament of Canada. October 16, 2013. Retrieved from: https://lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/Parliament/procedure/throneSpeech/speech412.

Governor General (2015). Making Real Change Happen: Speech from the Throne to open the First Session of the Forty-Second Parliament of Canada. December 4, 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/campaigns/speech-throne/making-real-change-happen.html.

Innocence Canada (2018). David Milgaard. Retrieved from: http://www.innocencecanada.com/exonerations/david-milgaard/.

Innocence Canada (2018). Guy Paul Morin. Retrieved from: http://www.innocencecanada.com/exonerations/guy-paul-morin/.

Innocence Project (2017). DNA Exonerations in the United States. Retrieved from: https://www.innocenceproject.org/dna-exonerations-in-the-united-states/.

King, A. (2015). In the future, DNA could put a face to the crime. The Irish Times. Retrieved from: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/in-the-future-dna-could-put-a-face-to-the-crime-1.2261282.

Kings College London (2017). New guide helps public understand role of DNA in criminal investigations. Retrieved from: https://phys.org/news/2017-01-role-dna-criminal.html.

Owusu-Bempah, A., & Wortley, S. (2014). Race, crime, and criminal justice in Canada. The Oxford Handbook of Ethnicity, Crime, and Immigration. Retrieved from: http://www.oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199859016.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199859016-e-020?rskey=5EjwS4&result=1.

Rodgers, G. (2015). Genomics – The Future of Forensic DNA Profiling. Huffington Post. Retrieved from: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/garry-rodgers/genomics-the-future-of-fo_b_8568204.html.

Royal Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh (2017). Forensic DNA Analysis: A Primer for Courts. Retrieved from: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/about-us/programmes/science-and-law/royal-society-forensic-dna-analysis-primer-for-courts.pdf.

Footnotes

- 1

Government of Canada. RCMP (2017). Evaluation of the RCMP’s Biology Casework Analysis, pages 10-12.

- 2

The Commissioner of the RCMP is accountable to the Federal Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness for the direction, management and operation of the National Police Services.

- 3

Government of Canada. RCMP (2017). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2016-17, page 4.

- 4

The provinces of Ontario and Quebec have established provincial forensic laboratories for the purpose of conducting biology casework analysis to support law enforcement in their jurisdictions. The RCMP is mandated under section 5.1(2) of the 1998 DNA Identification Act to conduct this analysis for other contract jurisdictions through its National Forensic Laboratories.

- 5

When DNA analysis was first introduced in Canada it was used only for criminal justice purposes to track DNA profiles through the Crime Scene Index and the Convicted Offenders Index. Following 2014 and 2018 amendments to the DNA Identification Act, the use of DNA analysis was broadened to include three humanitarian indices (Missing Persons Index, Relatives of Missing Persons Index, Human Remains Index), as well as two new indices to further support criminal investigations (Victims Index and Voluntary Donors Index). These new indices are currently in the process of being implemented and tracked in the NDDB.

- 6

Funds allocated internally within Public Safety Canada as part of the cost of operating the program.

- 7

Ibid.

- 8

Sections 3.6 and 3.7 require that transfer payment programs be designed, delivered and managed in a manner that is fair, accessible and effective for all involved and that the design and delivery of these programs respect the highest level of integrity, transparency, and accountability.

- 9

Royal Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh (2017). Forensic DNA Analysis: A Primer for Courts, page 7.

- 10

Deakin University (2017). How DNA analysis has revolutionized criminal justice: Dr. Annalisa Durdle. See also: Kings College London (2017). New guide helps public understand role of DNA in criminal investigations.

- 11

- 12

- 13

Government of Canada. Department of Justice Canada (2004). Report on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice: FPT Heads of Prosecutions Committee Working Group.

- 14

DNA analysis has also exonerated other people in Canada and elsewhere who had been convicted of serious offences. The Innocence Project in New York has reported 362 such DNA exonerations to date of writing this report (January 2019), including at least 20 for people on death row. Accordingly, 130 of these DNA exonerees had been wrongfully convicted for murders (Innocence Project (2017).

- 15

Government of Canada. RCMP (2017). Evaluation of the RCMP’s Biology Casework Analysis, pages 10-12.

- 16

Ibid.

- 17

Performance Data, Province of Ontario, 2013-14 to 2017-2018.

- 18

Ang, J. (2016). Advances in Portable DNA Analysis Brings us Closer to a Future with Medical Tricorders.

- 19

Familial searching is a process by which a DNA profile of interest in a criminal case is searched against the database. If there are no direct matches, it is then searched again in an attempt to find DNA profiles that are similar to the profile of interest and could belong to a close relative of the person who left the DNA at the crime scene (https://projects.nfstc.org/fse/13/13-0.html).

- 20

King, A. (2015). In the future, DNA could put a face to the crime. See also: Royal Society and the Royal Society of Edinburgh (2017). Forensic DNA Analysis: A Primer for Courts. See also: Deakin University (2017). How DNA analysis has revolutionized criminal justice: Dr. Annalisa Durdle.

- 21

Rodgers, G. (2015). Genomics – The Future of Forensic DNA Profiling. See also: Butler, J.M. (2015). The Future of DNA Analysis.

- 22

Government of Canada. RCMP (2016). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2015-16, page 2.

- 23

‘Contract provinces and territories’ refer to jurisdictions where RCMP contract police services are provided through Police Services Agreements. http://www.rcmp-grc.gc.ca/ccaps-spcca/contract-eng.htm.

- 24

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2017). 2016-2017 Departmental Results Report, page 4.

- 25

Government of Canada. Office of the Prime Minister (2015). Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Mandate Letter, November 12, 2015.

- 26

Government of Canada. Office of the Prime Minister (2015). Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Mandate Letter, November 12, 2015.

- 27

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2018). 2018-19 Departmental Plan, page 3.

- 28

Public Safety Canada, National Biology Casework Strategic Plan (2015–2020), page 1.

- 29

A wrongful conviction has been referred to as “a failure of Justice in the most fundamental sense (Government of Canada. Department of Justice (2004). Report on the Prevention of Miscarriages of Justice: FPT Heads of Prosecutions Committee Working Group).

- 30

Note that from the outset, the provinces of Ontario and Quebec chose to establish independent forensic laboratories for the purpose of conducting biology casework analysis to support law enforcement agencies in their jurisdictions. The RCMP was given the responsibility to conduct this analysis for all other jurisdictions through its National Forensics Laboratories.

- 31

Government Consulting Services, Public Works and Government Services Canada (2009). DNA Forensic Laboratory Services Cost and Capacity Review. Final Report.

- 32

It should be noted that a review of BCACP funding levels has not been completed since 2010. Given the unpreceded increase in demand for DNA analysis activities experienced by the recipients, some stakeholders have argued the need for undertaking a new study.

- 33

Government of Canada. RCMP (2017). Evaluation of the RCMP’s Biology Casework Analysis, page 7.

- 34

Public Safety Canada. Terms of Reference for the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Crime Prevention and Policing Committee, November 2016.

- 35

Ibid.

- 36

Public Safety Canada. Terms of Reference for the Federal/Provincial/Territorial DNA Working Group, March 2018.

- 37

Ibid.

- 38

The CPPC is co-chaired by the ADM, Community Safety and Countering Crime Branch and the FPT DNA Working Group is co-chaired by Director, Border Law Enforcement Strategies Division, Public Safety Canada.

- 39

There is also a National DNA Data Bank Advisory Committee that provides the NDDB with strategic guidance and direction on issues such as scientific advancements, matters of law, legislative changes, privacy issues and ethical practices. The members of the Committee are appointed by the Minister of Public Safety. The Committee reports to the Commissioner of the RCMP (Government of Canada. RCMP (2018). The National DNA Data Bank of Canada Annual Report 2017-18, p. 23).

- 40

Government of Canada. Public Safety Canada (2014). 2013-14 Evaluation of the Biology Casework Analysis Activities.

- 41

Public Safety Canada, National Biology Casework Strategic Plan (2015-2020), page 3.

- 42

This section requires departments to ensure that the administrative requirements for recipients are proportionate to the risk level. In particular, that monitoring, reporting and auditing reflect the risks specific to the program, the value of funding in relation to administrative costs, and the risk profile of the recipient.