Research Highlights

Crime Prevention: Local Adaptations of Crime Prevention Programs: A Toolkit

Introduction

This toolkit is a summary of a larger project that consists of a broad literature review reflecting current theory, practice and knowledge on the local adaptation of intervention programs in a variety of disciplines (See the literature review by Bania, Roebuck, & Chase, 2017) and key effective elements of evidence-based crime prevention programming (See the Key Effective Elements of Crime Prevention Programming by Bania, Roebuck, O'Halloran, & Case, 2017). This report integrates this information while attempting to answer the following question: How can evidence-based crime prevention initiatives be adapted from one successful program into new contexts with different people, cultures, and geographies, while remaining effective?

Program replication and program adaptation are both forms of “scaling out” a program – expanding the reach of an evidence-based program to other individuals in other settings. Here are some definitions:

- Implementation fidelity: How closely the program follows to the same elements, components, activities and tools developed and tested by the original developers in the original program.

- Program replication: An exact copy of the original evidence-based program applied to a new context.

- Program adaptation: The modification of an evidence-based program (EBP) or evidence-based intervention (EBI) to meet the unique needs of a specific situation within a certain population, location, and community capacity (i.e., fit).

While fidelity is important, program adaptation can have many benefits, such as:

- Improving community support through the involvement of various partners;

- Enhancing participation and satisfaction by being a better fit for client identities interests and needs;

- Enhancing positive outcomes by being more responsive; and

- Promoting longevity and sustainability of a program on the ground.

Program adaptation must be a carefully planned and intentional process where modifications are made through a series of assessments and decisions among service providers, program developers, researchers and other supporters to be productive. Unplanned program modifications (also known as program drift) that occur during implementation can lead to potential challenges and barriers to fidelity that can result in a loss of benefits to participants (Aarons et al., 2012).

This toolkit proposes the following sections:

- Recommendations;

- Framework for Local Adaptations of Crime Prevention Programs;

- Case Examples using the Framework for Local

- Adaptations of Crime Prevention Programs; and

- Appendixes which provide tools and other resources.

Recommendations

The following recommendations and frameworks are based on a review of the literature on program adaptation in various contexts (see Bania, Roebuck, & Chase, 2017) and reflect a comprehensive combination of current thinking and knowledge of good practices in program adaptation.

1. Recommendations for Program Funders and Policy Makers

- Invest in the systematic development and implementation of local crime prevention program adaptations: Ensure that organizations and teams on the ground have the adequate knowledge, skills, and resources to develop and implement strong examples of adapted programs.

- Support mixed-methods evaluations of local crime prevention program adaptations in diverse communities: Mixed methods evaluations of “what works, for who, under what circumstances, and why” may be most appropriate to further develop and legitimize this field of intervention and inquiry in both political and academic contexts (Westhorp, 2014).

2. Recommendations for Local Adaptations on the Ground

Assess site readiness and support key drivers:

- Support leadership drivers (i.e., effective management strategies): Create and support an appropriately skilled implementation team to ensure ongoing commitment, consistency, responsibility, and accountability;

- Support competency drivers (i.e., skilled, qualified, and supported staff): Develop the necessary capacity (knowledge, skills, and resources) before program implementation and during program implementation to promote best results; and

- Support organization drivers (i.e., good administration and project management) (See Bain, Roebuck, & Chase, 2017).

Balance empirical evidence with local context and experience:

- Include and value the experiences and expertise of various professionals (e.g., community stakeholders, staff, and target population representatives) in all stages of the adaptation process;

- Promote awareness of power relations, and positive conflict resolution; and

- Encourage safe and open discussion when decision-making.

Use appropriate motives and reasoning when making program adaptations:

- See the 'Green Light, Yellow Light, and Red Light Adaptations' (See Appendix 1)

Avoid fundamental changes to key elements of an intervention such as:

- Modifications to the original underlying theoretical approach of a program;

- Significant changes to dosage (number/length of sessions, program duration);

- Eliminating key messages or skills to be developed by participants; and

- Using less qualified personnel and less staff than recommended.

Make modifications that respect and reflect both the surface structure (i.e., language) and deep structure (i.e., histories and values) of the client population culture:

- Assess program components through a cultural lens and adapt where necessary (i.e., program knowledge base, language, staffing, training, goals, concepts, formats, methods, and settings).

Use a strengths-based approach and capacity-building lens:

The strength-based approach views people and communities as capable and able to draw on their current assets and learn new skills to manage their own wellbeing in sustainable ways (Cox, 2008; Hammond & Zimmerman, 2012; Roebuck, Roebuck, & Roebuck, 2011). The strength-based approach also:

- Supports people to feel hopeful;

- Develops resiliency in the face of obstacles (Alberta Mentoring Partnership, 2010; Cox, 2008); and

- Helps with community buy-in.

Use mixed methods and community-based participatory research to guide assessment and evaluation:

- Incorporate both quantitative and qualitative methods into the program adaptation planning and evaluation processes;

- Use participatory research methods to facilitate and sustain participant engagement, and to collect the most meaningful and reliable data possible;

- Explore culturally appropriate methodologies when working with diverse populations (e.g., Indigenous research methods); and

- Use selection of evaluation methodologies that take into consideration how to increase evaluation capacity and sustain evaluative thinking into the initiative over time.

Use an intentional, systematic approach to balance fidelity and fit:

Balancing fidelity and fit is best addressed through a planned, organized, and systematic approach which uses a framework to:

- Build a strong collaborative foundation for the program;

- Identify and plan modifications;

- Document the adaptation process;

- Reflect on the effectiveness of the adjustments; and

- Further refine the model as necessary.

Framework for Local Adaptations of Crime Prevention Programs

This section of the document contains the program adaptation framework for local crime prevention programming which was developed based on a review of the vast program adaptation literature (See Bania, Roebuck, & Chase, 2017).

The principles and best practices from other program adaptation models are built into this framework. The following description and table (See Table 1) outline the action steps for each of these guidelines, and suggests supporting resources to help teams work through this framework that are provided in the appendices section of this document.

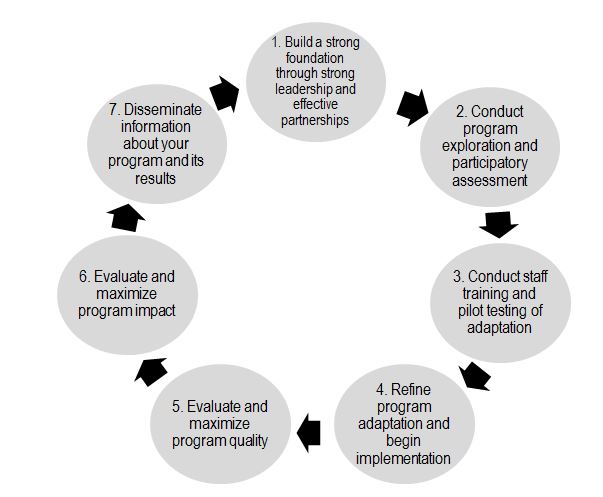

Framework for Local Program Adaptations

- Build a strong foundation through strong leadership and effective partnership.

- Conduct program exploration and participatory assessment to select an appropriate evidence-based program and decide on its necessary adaptations. Create the first collaborative version of the Program Fidelity & Adaptation Plan (See Appendix 2).

- Conduct staff training and pilot testing of the adaptation.

- Refine program adaptation and begin implementation.

- Evaluate and maximize program quality.

- Evaluate and maximize program impact.

- Disseminate information about your program and its results.

Image Description

The framework for Local Program Adaptations is a cyclical, 7-step process which is represented using a circular graph. Moving in a clockwise fashion, the stages illustrated are (1) Build a strong foundation through strong leadership and effective partnership, (2) Conduct program exploration and participatory assessment, (3) Conduct staff training and pilot testing of the adaptation, (4) Refine program adaptation and begin implementation, (5) Evaluate and maximize program quality, (6) Evaluate and maximize program impact, and (7) Disseminate information about your program and its results.

| Guidelines | Action Steps | Tools & Resources |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Build a strong foundation through strong leadership and effective partnership | ||

| 1.1 Put in place strong leadership and effective partnership processes |

|

|

| 1.2 Ensure early and ongoing community and stakeholder involvement |

|

|

| 2. Conduct program exploration and participatory assessment to select an appropriate evidence-based program and decide on necessary adaptations | ||

| 2.1 Conduct a structured assessment to determine readiness, fit and feasibility |

|

|

| 2.2 Analyze core program components and identify what in the original program needs to be adapted |

|

|

| 2.3 Decide how the program should be adapted and through which specific modifications |

|

|

| 2.4 Develop program implementation guides and toolkits for staff |

|

|

| 3. Conduct staff training and pilot testing of the adaptation | ||

| 3.1 Provide training and technical assistance to program staff |

|

|

| 3.2 Test the program and its adaptation through a pilot study |

|

|

| 4. Refine program adaptation and begin implementation | ||

| 4.1 Refine Program Fidelity and Adaptation Plan and adjust all program material accordingly |

|

|

| 4.2 Refresh staff training to reflect final program adaptation |

|

|

| 4.3 Begin implementing the new program in a formal way |

|

|

| 5. Evaluate and maximize program quality | ||

| 5.1 Perform a process evaluation to measure fidelity AND adaptation | Develop and implement a Process Evaluation plan to:

|

|

| 5.2 Continue to make program adaptations as necessary to maximize program quality |

|

|

| 6. Evaluate and maximize program impact | ||

| 6.1 Perform an impact evaluation to measure program outcomes |

|

|

| 6.2 Continue to make program modifications as necessary to maximize program impact |

|

|

| 7. Disseminate information about your program and its results | ||

| 7.1 Share information about your program within your community and more broadly |

|

|

Case Examples using the Framework for Local Adaptations of Crime Prevention Programs

Below are two illustrative case examples that apply the Framework for Local Adaptations of Crime Prevention Programs to two of the evidence-based crime prevention programs reviewed in the above-mentioned report and highlight the considerations to think through when conducting the local adaptation of an evidence-based crime prevention program: case example 1 is the local adaptation of the OJJDP Comprehensive Gang Model in a Canadian City and case example 2 is the local adaptation of the Multisystemic Therapy (MST) for Indigenous youth.

Case Example 1: Local Adaptation of the OJJDP Comprehensive Gang Model in a Canadian City

Evidence-Based Program: the Comprehensive Gang Model

The OJJDP Comprehensive Gang model is a comprehensive and collaborative approach designed to reduce and prevent gang violence while involving five core strategies which include: community mobilization, opportunities provision, social intervention, suppression, and organizational change and development (National Gang Center, n.d.). See Table 2 for more information.

Description:

A relatively large Canadian city has experienced rising rates of gang-related violence with increasing involvement from youth who are racialized and living in parts of the city with concentrations of economic inequity and higher needs for support. Community leaders have been asking the city to work with them to proactively address the underlying causes of gang-related violence rather than targeting law enforcement resources in their neighbourhoods. A group of stakeholders led by the city's community safety committee are asked to identify an evidence-based program to address gang-related violence and adapt it to the complexity of the diverse cultural profile of the city.

Demographic Information:

Population: CMA 1,000,000

Diversity: 38% of the population self-identify as visible minorities as categorized by the Canadian Census, and 40% of the population speak a language other than English at home.

Formal Community Resources:

The city has strong networks of community health and resource centres, service providers including many for youth, neighbourhood associations, faith groups, and recreational programming.

The following table presents the program adaptation framework for local crime prevention programming, with key questions and considerations for implementing the Comprehensive Gang Model in the context of the Canadian city described above.

| Guidelines | Key Considerations for this Initiative |

|---|---|

| 1. Build a strong foundation through strong leadership and effective partnership | |

| 1.1 Put in place strong leadership and effective partnership processes | The Comprehensive Gang Model will require a high level of engagement across the city. What groups and networks that can play a role in addressing gang activity already exist in the city? The first phase of establishing leadership and partnerships will be time intensive. It may be possible to harness existing networks and/or committees within the city to gather key stakeholders and benefit from existing partnership and information or resource sharing protocols. According to the program model: identify the lead agency; develop a steering committee; hire a project director; identify a research/evaluation partner; and form the research/evaluation team. Based on the existing framework of the Comprehensive Gang Model, the following players would need to be included to build a strong foundation and work towards effective partnerships:

Consider whose voices should and will be heard. What are ways to involve former gang members and have an informed local gang perspective? Are there already young adults in the community who identify as former gang members, publicly? Negotiate shared priorities and shared resources with and amongst key players. Take time to develop the project team, decision-making process, communication process, and steps to sustainability – these are the foundation of the Comprehensive Gang Model – the model won't work if these community development pieces are not put into place. When considering resources, ensure there is investment in developing these processes. |

| 1.2 Ensure early and ongoing community and stakeholder involvement | |

| 2. Conduct program exploration and participatory assessment to select an appropriate evidence-based program and decide on necessary adaptations | |

| 2.1 Conduct a structured assessment to determine readiness, fit and feasibility | Consider integrating OJJDP's assessment guide in this phase, when assessing the needs and strengths of the community and target population: (https://www.nationalgangcenter.gov/Content/Documents/Assessment-Guide/Assessment-Guide.pdf) Ensure the assessment includes an articulation not just of needs, but also of the strengths within the community. For example:

Incorporate cultural adaptation into this process. Involve those with lived experience: former gang members, current gang members, key community experts, family members of gang-involved youth. Allow space for personal sharing. Develop ways to receive feedback on the process from a broader group of community members and family members. Check individual and group assumptions and biases around gangs and cultural groups within the city. Verify and demystify understandings of gang activity and membership through local research that clearly defines the problem. |

| 2.2 Analyze core program components and identify what in the original program needs to be adapted | |

| 2.3 Decide how the program should be adapted and through which specific modifications | Use the Program Fidelity & Adaptation Plan template in Appendix 2 as a starting point. For this initiative, consider the following:

|

| 2.4 Develop program implementation guides and toolkits for staff | Use a variety of communication styles and tools – written, audio-visual, interactive. Use formats and imagery that represent the ethnically diverse lens of the program. |

| 3. Conduct staff training and pilot testing of the adaptation | |

| 3.1 Provide training and technical assistance to program staff | Use a variety of communication styles and tools – written, audio-visual, interactive. Use formats and imagery that represent the ethnically diverse lens of the program. Allow for hands-on practice, troubleshooting, and collaborative problem-solving throughout initial and ongoing training. Consider who the trainers should be - how will cultural competence be included and modeled in the training? Consider how to adapt the training material to the diverse players involved in the comprehensive strategy, for example: police, faith groups, community leaders, service providers. |

| 3.2 Test the program and its adaptations through a pilot study | Determine:

|

| 4. Refine program adaptation and begin implementation | |

| 4.1 Refine Program Fidelity and Adaptation Plan and adjust all program material accordingly | Intelligent Failure & Learning Loops: Identify successes and failures and explore the broader structural, political, community, and personal realities that contributed to each – see Appendix 8 for a template. Information Sharing and Consultation: Report the outcomes of the pilot back to all stakeholders involved in the development of the adaptation, including partners and community members. This might include a public meeting to discuss the outcomes and invite more consultation on the ways community members have been impacted by the program and to engage in broader problem-solving around remaining challenges prior to the broader implementation. Training: Provide refresher training to partners, including experiential learning opportunities that draw on real-life examples from the pilot. Refine and Implement Program Adaptation: Ensure that lessons from the pilot are integrated into the adaptation and start to roll out the full program, ensuring that adequate support is provided to all partners and that there is continuous attention to reflection and learning. |

| 4.2 Refresh staff training to reflect final program adaptations | |

| 4.3 Begin implementing the new program in a formal way | |

| 5. Evaluate and maximize program quality | |

| 5.1 Perform a process evaluation to measure fidelity AND adaptation | Continue a participatory, community-based process by involving participants, partners, community members, and former gang members in evaluation processes. Key considerations for the evaluation of collaborative initiatives:

|

| 5.2 Continue to make program adaptations as necessary to maximize program quality | |

| 6. Evaluate and maximize program impact | |

| 6.1 Perform an impact evaluation to measure program outcomes | Continue a participatory, community-based process by involving participants, partners, community members, and former gang members in evaluation processes. Key considerations for the evaluation of collaborative initiatives:

|

| 6.2 Continue to make program modifications as necessary to maximize program impact | |

| 7. Disseminate information about your program and its results | |

| 7.1 Share information about your program within your community and more broadly | Prepare and implement a Knowledge Dissemination Plan |

Case Example 2: Local Adaptation of the Multisystemic Therapy (MST) for Indigenous Youth

Evidence-Based Program: Multisystemic Therapy (MST)

Multisystemic Therapy (MST) is an intensive family and community based treatment program that addresses environmental systems that impact chronic and violent juvenile offenders including their homes, families, friends, neighbourhoods, and schools (Multisystemic Therapy, 2017). This program recognises that each system plays a role and requires attention when implementing effective changes to improve the lives of youth and their families. See Table 3 for more information.

Description:

An agency specializing in mental health supports located in a rural northern Canadian town has been noticing a growing number of Indigenous youth cycling through community services, including the emergency shelter, detention facility, emergency room, and hospitalizations for substance misuse and psychiatric care. In response to this, the agency would like to adapt Multisystemic Therapy to this setting with a focus on supporting young Indigenous peoples in the community.

Demographic Information:

Population: approximately 12,000 people

Diversity: 30% Indigenous peoples and 70% Non-Indigenous peoples

Formal Community Resources:

The town has a small community hospital, an emergency shelter for adults and youth, a community resource centre with mental health programs (including counselling services), day programming for various target populations (e.g., parent/baby drop in, adults living with disabilities, seniors drop-in) and a recreational centre with various programming. They also have various community groups/associations (e.g., faith-based, cultural, and recreational groups).

The following table presents the program adaptation framework for local crime prevention programming, with key considerations for implementing Multisystemic Therapy (MST) with Indigenous youth in a rural setting. This includes reflections on how traditional Indigenous values, knowledge, and norms can be used to adapt the program and its evaluation to ensure cultural safety and relevance.

Note: It is important to note that traditional Indigenous philosophies, and the Western concepts of a 'program' and of research, represent two different worldviews. The first relies on concepts of interdependence and oral teachings, while the latter focuses on standardization and experimental science. As such, areas of tension will naturally arise when exploring this topic. Nonetheless, there are commonalities in the teachings of each approach, which can hopefully inspire ways for effectively supporting Indigenous youth at the local level.

| Guidelines | Key Considerations for the Initiative | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Build a strong foundation through strong leadership and effective partnership | ||

| 1.1 Put in place strong leadership and effective partnership processes | Due to the history of colonialism and resulting harm done to Indigenous peoples and communities by Western policies, practices, research, and programming, it is important that the Indigenous community have influence over the initiative and control in decision making. A meaningful representative of the Indigenous community must play a leadership role through the Lead Agency, Advisory Group, and/or implementation team. Whenever possible, the Lead Agency should already be operating within an Indigenous Framework, or have strong leadership from this community.

Consider whose voices should and will be heard in the design and implementation of the initiative. What are ways to involve local Indigenous Elders, groups and peoples? Negotiate shared priorities and shared resources with and amongst key players. Take time to develop the project team, decision-making processes, communication process, and steps to sustainability. When considering resources, ensure there is investment in developing these collaborative processes. Ensure that all types of knowledge, input, and expertise are valued and acknowledged. |

|

| 1.2 Ensure early and ongoing community and stakeholder involvement | ||

| 2. Conduct program exploration and participatory assessment to select an appropriate evidence-based program and decide on necessary adaptations | ||

| 2.1 Conduct a structured assessment to determine readiness, fit and feasibility | In the aftermath of historical trauma, Indigenous practices for healing involve decolonization (learning and understanding traditional cultural values and teachings), recovery from trauma (an opportunity to understand and grieve losses), and ongoing healing (a commitment to gaining balance). In Western research on effective youth programming, a connection to one's culture has been shown a key developmental asset that promotes wellbeing. In this context, several strategies and programs have emerged that are considered evidence-informed by Western standards (i.e., supported by research), and responsive to Indigenous philosophies and experiences (i.e., culturally appropriate). Key strategies for supporting Indigenous youth in meaningful and appropriate ways include: (1) ensuring cultural safety, (2) working from strengths, and (3) providing trauma-informed supports (see Bania, 2017). In this sense, Multisystemic Therapy appears to be a reasonable fit since it focuses on collaborative decision-making with participants, trauma-informed support, and enhancing strengths. Its engagement with multiple systems also fits with the Indigenous value of interconnectedness and supports Indigenous learning by drawing on and nurturing relationships within families, and the community (Canadian Council on Learning, 2009). For this initiative, check individual and group assumptions and biases around Indigenous youth and families in the community. Verify, clarify and demystify understandings of local Indigenous peoples through local research that clearly defines the context from multiple perspectives. Take time to identify and connect with the underlying framework, theory, and assumptions of MST and how it may intersect with or conflict with Indigenous values, beliefs, and assumptions (e.g., medicine wheel, perspectives on family) (see Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health, 2016). As above, it is essential that key players from the Indigenous community are meaningfully involved and leading through the complete process, especially when agreeing upon the philosophy of care and guiding beliefs and assumptions. Key capacity considerations include:

|

|

| 2.2 Analyze core program components and identify what in the original program needs to be adapted | ||

| 2.3 Decide how the program should be adapted and through which specific modifications | Use the Program Fidelity & Adaptation Plan template in Appendix 2 as a starting point. For this initiative, consider the following:

Trauma-Informed Resource Guide by the British Columbia Centre of Excellence for Women's Health: https://bccewh.bc.ca/2017/03/trauma-informed-practice-resources/ Manitoba Trauma Information and Education Centre: www.trauma-informed.ca

Consider how to support modern conceptions of healing for Indigenous peoples such as (1) decolonization, (2) recovery from past trauma, and (3) the ongoing healing journey (see Archibald, 2006; Bania, 2017; Wabano, 2014).

|

|

| 2.4 Develop program implementation guides and toolkits for staff | Use a variety of communication styles and tools – written, oral, audio-visual, interactive. Use formats and imagery that represent the local Indigenous culture. |

|

| 3. Conduct staff training and pilot testing of the adaptation. | ||

| 3.1 Provide training and technical assistance to program staff | In addition to training in MST, ensure local MST therapists and supervisors have the knowledge and skills for cultural competency. Use a variety of communication styles and tools – written, oral, audio-visual, interactive. Use formats and imagery that represent the local Indigenous culture. Provide training in local language whenever possible. Allow for hands-on practice, troubleshooting, and collaborative problem-solving throughout initial and ongoing training. Consider who the trainers should be - how will cultural competence be included and modeled in the training? Consider how to adapt the training material to the diverse players involved in the comprehensive strategy, for example: police, school officials, faith groups, community leaders, service providers, etc.? |

|

| 3.2 Test the program and its adaptations through a pilot study | Determine:

|

|

| 4. Refine program adaptation and begin implementation | ||

| 4.1 Refine Program Fidelity and Adaptation Plan and adjust all program material accordingly | Intelligent Failure & Learning Loops: Identify successes and failures and explore the broader structural, political, community, and personal realities that contributed to each – see Appendix 8 for a template. Information Sharing and Consultation: Report the outcomes of the pilot back to all stakeholders involved in the development of the adaptation, including partners and community members. This might include a public meeting to discuss the outcomes and invite more consultation on the ways community members have been impacted by the program and to engage in broader problem-solving around remaining challenges prior to the broader implementation. Training: Provide refresher training to staff and partners, including experiential learning opportunities that draw on real-life examples from the pilot. Refine and Implement Program Adaptation: Ensure that lessons from the pilot are integrated into the adaptation and start to roll out the full program, ensuring that adequate support is provided to all staff and partners and that there is continuous attention to reflection and learning. |

|

| 4.2 Refresh staff training to reflect final program adaptations | ||

| 4.3 Begin implementing the new program in a formal way | ||

| 5. Evaluate and maximize program quality | ||

| 5.1 Perform a process evaluation to measure fidelity AND adaptation | Continue a participatory, community-based process by involving participants, partners, and community members in evaluation processes. Key considerations for research and evaluation in Indigenous contexts:

Consult the following resources:

Use the results to modify your Program Fidelity & Adaptation Plan (see Appendix 2) to continue to assess and meet local needs. |

|

| 5.2 Continue to make program adaptations as necessary to maximize program quality | ||

| 6. Evaluate and maximize program impact | ||

| 6.1 Perform an impact evaluation to measure program outcomes | Continue a participatory, community-based process by involving participants, partners, and community members in evaluation processes. Key considerations for research and evaluation in Indigenous contexts:

Consult the following resources:

Use the results to modify your Program Fidelity & Adaptation Plan (see Appendix 2) to continue to assess and meet local needs. |

|

| 6.2 Continue to make program modifications as necessary to maximize program impact | ||

| 7. Disseminate information about your program and its results | ||

| 7.1 Share information about your program within your community and more broadly | Prepare and implement a Knowledge Dissemination Plan | |

Appendix 1: Green Light, Yellow Light, Red Light Adaptations

Program adaptations have been categorized under three categories of appropriateness using a traffic light analogy (O'Conner et al., 2007; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012; Bania, Roebuck, & Chase, 2017). Consider these guidelines when program adaptation is being considered.

Green Light Adaptations: |

Go for it! These adaptations are appropriate and are encouraged so that program activities better fit the age, culture, and context of the population. In many cases these changes should be made because they ensure the program is current and relevant to the community.

|

Yellow Light Adaptations: |

Proceed with caution! These adaptations should be made with caution so that the core components are adhered to and the adaptation does not cause other issues (e.g. time constraints, competition of topics, etc.). When making yellow light adaptations, it is recommended to consult more detailed adaptation tools and/or an expert in the evidence-based program, such as the model developer (if available) before making the change.

|

Red Light Adaptations: |

Stop! These adaptations remove or alter key aspects of the program that will likely result in weakening the evidence-based program's effectiveness.

|

Appendix 2: Program Fidelity & Adaptation Plan Template

(Bania, Roebuck, & O'Halloran, 2017)

This Program Fidelity and Adaptation Plan template was developed using tips from several sources and incorporating findings from the literature review by Bania, Roebuck and Chase (2017). It is designed to help teams assess their program and document decisions made around program adaptations to some of the key elements of any program.

Complete the fidelity and adaptation information below in order to guide your local adaptations. Identify which components maintain fidelity to the original evidence-based program, and which components will be adapted for your specific program purposes. Ensure to explain your changes.

Name of the program |

||

Program Adaptation Plan Version |

||

Date |

||

EVIDENCE-BASED PROGRAM |

||

GOALS & OBJECTIVES |

||

WILL ANY CHANGES BE MADE TO THE GOALS AND OBJECTIVES of the original program for your purposes? |

||

EXPECTED OUTCOMES |

||

TARGET POPULATION |

To whom is the program being delivered? |

|

As described in the original program: Has this component been changed? (tailoring, adding, removing, replacing, etc.)

Date of change: Reason for change (select all that apply):

Describe the change and rationale for the change – what it used to be, what it looks like now in practice, and why it changed. Will it be necessary to modify your program and evaluation design, forms, or tools to accommodate this change?

If no, why are no changes necessary? If yes, briefly describe what changes will be made and when. |

||

SETTING |

Where does the intervention/program take place? |

|

As described in the original program: Has this component been changed? (tailoring, adding, removing, replacing, etc.)

Date of change:

Describe the change and rationale for the change – what it used to be, what it looks like now in practice, and why it changed. Will it be necessary to modify your program and evaluation design, forms, or tools to accommodate this change?

If no, why are no changes necessary? If yes, briefly describe what changes will be made and when. |

||

STAFFING REQUIREMENTS |

Who delivers the program? (e.g. staff vs. volunteers, training requirements, staff to client ratio) |

|

As described in the original program: Has this component been changed? (tailoring, adding, removing, replacing, etc.)

Date of change:

Describe the change and rationale for the change – what it used to be, what it looks like now in practice, and why it changed. Will it be necessary to modify your program and evaluation design, forms, or tools to accommodate this change?

If no, why are no changes necessary? If yes, briefly describe what changes will be made and when. |

||

MAIN STRATEGIES AND PRACTICES |

How is the program delivered? (e.g. workshops, classes, home visits, role play, conflict resolution, cognitive behavioural therapy, employment training, treatment modalities, etc). |

|

As described in the original program: Has this component been changed? (tailoring, adding, removing, replacing, etc.)

Date of change:

Describe the change and rationale for the change – what it used to be, what it looks like now in practice, and why it changed. Will it be necessary to modify your program and evaluation design, forms, or tools to accommodate this change?

If no, why are no changes necessary? If yes, briefly describe what changes will be made and when. |

||

PROGRAM TOOLS |

E.g. curriculum, program materials, videos, manuals, order of sessions or material, language. |

|

As described in the original program: Has this component been changed? (tailoring, adding, removing, replacing, etc.)

Date of change:

Describe the change and rationale for the change – what it used to be, what it looks like now in practice, and why it changed. Will it be necessary to modify your program and evaluation design, forms, or tools to accommodate this change?

If no, why are no changes necessary? If yes, briefly describe what changes will be made and when. |

||

DOSAGE |

What is the quantity and frequency of the program/intervention? |

|

|

||

DURATION |

What is the required period of time of the program? |

|

As described in the original program: Has this component been changed? (tailoring, adding, removing, replacing, etc.)

Date of change:

Describe the change and rationale for the change – what it used to be, what it looks like now in practice, and why it changed. Will it be necessary to modify your program and evaluation design, forms, or tools to accommodate this change?

If no, why are no changes necessary? If yes, briefly describe what changes will be made and when. |

||

OTHER NOTES |

||

Appendix 3: The VSP Tool: A Diagnostic and Planning Tool to Support Successful and Sustainable Initiatives (CICYC, 2008)

The “VSP Tool: A Diagnostic and Planning Tool to Support Successful and Sustainable Initiatives” was developed in 2008 by the Centre for Initiatives on Children, Youth and Community (CICYC) at Carleton University in Ottawa, ON (Canada). It is an approach that is based on the lessons learned through research on sustainable crime prevention initiatives in Canadian communities. It is designed to help communities plan and carry out sustainable community initiatives. It offers key principles to consider, important lessons learned from research on sustained community efforts, and poses a series of questions to help develop local, collaborative values, structures and processes. “Katujjiqatigiiniq: Community Action to Sustain a Safer and Healthier Community” is an adaptation of the VSP Tool for communities in Canada's north. It is based on research and consultation with the Government of Nunavut's Community Justice Specialists and research in six communities in Nunavut. The approach is explained in detail at: http://carleton.ca/cicyc/about/.

Appendix 4: The Community Toolbox

The Community Tool Box is a service of the Work Group for Community Health and Development at the University of Kansas (United States). The Tool Box is part of the Work Group's role as a designated World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Community Health and Development. The Tool Box comprises over 40 chapters on topics such as: creating and maintain partnerships; assessing community needs and resources; developing strategic plans and action plans; building leadership; enhancing cultural competence. It also contains more than 15 toolkits on these issues.

Visit the Tool Box and access its resources at: http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents

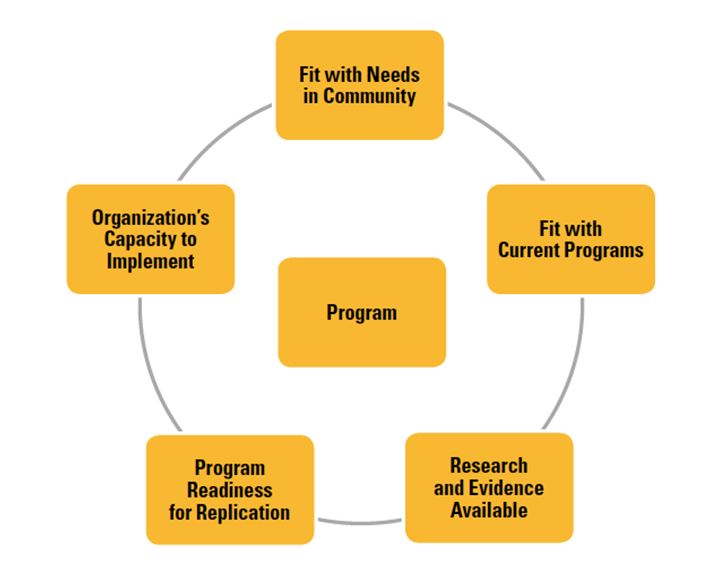

Appendix 5: Pentagon Tool

Taken from p. 29 of Savignac, J. & Dunbar, L. (2014). Guide on the Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs: What Do We Know So Far? Ottawa: Public Safety Canada. Adapted from 'The Hexagon Tool' by Laurel Kiser, Karen Blase and Dean Fixsen (2013). Based on work from Lauel Kiser, Michelle Zabel, Albert Zachik and Joan Smith (2007). Refer to Savignac & Dunbar (2014) for a detailed description of the areas listed in the Figure and a scoring chart. The publication is available through Public Safety Canada at: https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/gd-mplmnttn-vdnc-prgrms/index-en.aspx

Image Description

This chart illustrates the Pentagon Tool program which consists of the following parts:

- Fit with Needs in Community,

- Fit with Current Programs,

- Research and Evidence Available

- Program Readiness for Replication, and

- Organization's Capacity to Implement

Appendix 6: Experimental Learning Tips & Tools

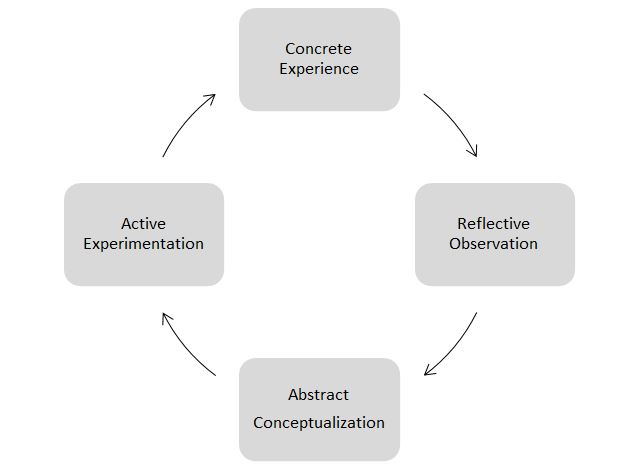

“Experience plus reflection equals learning.” – John Dewey

Experiential learning helps people apply theory to practice and 'learn by doing'. It's a hands-on approach where participants reflect on their learning throughout an activity, using critical analysis and synthesis. The goals of experiential learning are to explore and expand upon the expertise of participants and provide knowledge that can be applied to real-life situations in the future. This includes the use of interactive activities and discussions, which help learners understand theories and reasoning, then reflect on practical applications in their unique program settings.

Adaptation of evidence-based programs can be complex. Training that invites participants to solve real challenges and apply their learning helps to develop the needed skills to be effective in future adaptations. David Kolb developed the following experiential learning cycle:

Image Description

The chart above illustrates the four stages in David Kolb's experiential learning cycle. Moving in a counterclockwise fashion, the cycle begins with Concrete Experience, which leads to Reflective Observation, followed by Abstract Conceptualization, and finally Active Experimentation.

Facilitators of experiential learning limit their use of exerting power and control and act as a guide, resource, and support to ensure participants are in control of their own learning (Schwartz, n.d.). Best practices for experiential learning include:

- Providing opportunities that match diverse learning styles (see figure below);

- Framing learning as an opportunity to both gain and share knowledge and skills; and

- Using reflection so learners can connect theory and practical experience (Coker & Porter, 2015; Schwartz, n.d.)

Appendix 7: Intelligent Failure & Learning Loops Worksheet

How can we improve a program as we move forward? One way is by embracing learning from program failures like unmet goals, missed opportunities, and poor program take-up. Learning through failure is good for an organization; it leads to innovation, resilience, and adaptability.

In 1992, Sim Sitkin coined the term “intelligent failure” to describe the process of maximizing a failure by learning from it. We can make room for failure in program development by committing to fail fast and efficiently – we can set up monitoring and evaluation processes to identify failures early on, reflect on them, and make program changes in light of these failures.

Intelligent failure is linked to organizational adaptability. While a success may lead to reliability and stability, a failure can move an organization forward in new ways. Creating accepting cultures in our organizations and being open to failure can lead to healthy risk-taking and breakthrough ideas (Good, 2014, February 26; Sitkin, 1992). Sitkin (1992) said, “not all failures are equally adept at facilitating learning”.

Sitkin (1992) identified four ways organizations can promote intelligent failure:

- Increase the focus on process rather than outcomes;

- Legitimate intelligent failure;

- Engender and sustain individual commitment to intelligent failure through organizational culture and design;

- Emphasize failure management systems rather than individual failure.

See the following resources to find out more about intelligent learning and how organizations use failure to move forward. You can also use the learning loops worksheet below as a tool throughout the program adaptation process, particularly as you move from a pilot stage to full program implementation.

Resources

- Engineers Without Borders. Failure Reports.http://legacy.ewb.ca/en/whoweare/accountable/failure.html

- Fail Forward (2014). Fail Forward Toolkit. https://failforward.org/resources/#materials

- Good, A. (2014, May 20). Intelligent Failure Learning & Innovation Loop. https://failforward.org/if-loop/

- Good, A. (2014, February 26). What is Intelligent Failure? https://failforward.org/what-is-intelligent-failure/

- Harvard Business Review (2011, April). The Failure Issue. https://hbr.org/archive-toc/BR1104

- Sitkin, S. B. (1992). Learning through failure: The strategy of small losses. Research in Organizational Behavior, 14, 231-266. http://mujtama3i.org/wp

content/uploads/2015/06/%D8%A7%D8%B6%D8%BA%D8%B7-%D9%87%D9%86%D8%A73.pdf

Learning Loops Worksheet

Image Description

The above graphic is a representation of the Learning Loops Worksheet, a fillable form in which users identify a complication that has arisen in the program implementation or evaluation, and then document the successes and challenges in relation to the identified implementation issue. Aside from the identification of a complication, the user is asked “What didn’t go as planned” and “What went really well” in relation to the complication; why things didn’t go as planned/ went really well; and what broader structural, community, political and systemic factors were in play to impact why things didn’t go as planned/went really well. Other questions asked to the user are “What program components would you change? / What would you keep?” and “What program goals, beliefs and expectations would you change? / What would you keep?”

References

- Aarons, G., Green, A. E., Palinkas, L., Self-Brown, S., Whitaker, D. J., Lutzker, J. R., Chaffin, M. J. (2012).

Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence-based child maltreatment intervention.

Implementation Science, 7(1), 32. - Alberta Health Services. (n.d.). Knowledge Translation Planning Template. Retrieved from http://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/Infofor/Researchers/if-res-sktt-plan-checklist.pdf

- Alberta Mentoring Partnership. (2010). Start Mentoring. Retrieved from https://albertamentors.ca/start-mentoring/

- Archibald, L. (2006). Decolonization and Healing: Indigenous Experiences in the United States, New Zealand, Australia and Greenland. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation.

- Bania, M. (2017). Culture as Catalyst: Preventing the Criminalization of Indigenous Youth. Ottawa: Crime

Prevention Ottawa. Retrieved from http://www.crimepreventionottawa.ca/Media/Content/files/Publications/Youth/Culture%20as%20Catalyst-Prevention%20the%20Criminalization%20of%20Indigenous%20Youth-final%20report.pdf - Bania, M., Roebuck, B., & Chase, V. (2017). Local adaptations of crime prevention programs: Finding the optimal balance between fidelity and fit– A Literature Review. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada

- Bania, M., Roebuck, B., & O'Halloran, B. (2017). Local adaptations of crime prevention programs: Finding the optimal balance between fidelity and fit–Guidelines and recommendations. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

- Bania, M., Roebuck, B., & O'Halloran, B. (2017). Local adaptations of crime prevention programs: Finding the optimal balance between fidelity and fit– Illustrative case examples. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

- Bania, M., Roebuck, B., O'Halloran, B., & Chase, V. (2017). Local adaptations of crime prevention programs: Finding the optimal balance between fidelity and fit– Key effective elements of crime prevention programs. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

- Bory, F., & Franks, R. (2016). Assessing Readiness to Implement. Presentation to the CAMH Implementation Learning Institute. June 22, 2016, Toronto Canada.

- Better Evaluation. (n.d.). Start Here. Retrieved from http://www.betterevaluation.org

- Canadian Council on Learning (2009). The State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success. Ottawa: CCL.

- Canadian Council on Learning (2009). The State of Aboriginal Learning in Canada: A Holistic Approach to Measuring Success. Ottawa: CCL.

- Capacity Canada. (n.d.). Evaluation Activates Non-Profit Innovation. Retrieved from https://capacitycanada.ca/evalu/

- Centre for Initiatives on Children, Youth and Community. (2008). Values, Structures, Processes (VSP) Tool. Retrieved from http://carleton.ca/cicyc/wp-content/uploads/VSP_toolkit1.pdf

- Centre for Initiatives on Children, Youth and Community. (2008).VSP Tool Adapted for Canada's North. Retrieved

from http://carleton.ca/cicyc/wp-content/uploads/VSP_toolkit_Nunavut1.pdf - Coker, J. S., & Porter, D. J. (2015). Maximizing experiential learning for student success. Change, January/ February, 66-72.

- Community Tool Box. (2016). Table of Contents. Retrieved from http://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents

- Cox, K. (2008). A roadmap for building on youths' strengths. In E. J. Bruns & J. S. Walker (Eds.), The Resource Guide to Wraparound (pp. 19–24). Portland, OR: National Wraparound Initiative, Research and Training

- Center for Family Support and Children's Mental Health. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost. com/login. aspx? direct=true&profile=ehost&scope=site&authtype=crawler&jrnl10895701&AN=311

23751&h=vJS4NgJ59HEzn5YxIju9MzEnX7Mt5+3N7uJN6qoVfVDxabtWjajnImWotbfyEL/sqvXhsEIhII21vK0CPYwvw==&crl=c - Cox, K. (2008). Tools for building on youth strengths. Reclaiming Children and Youth, 16(4), 19-24.

- Cummins, M., Goddard, C., Formica, S., Cohen, D., & Harding, W. (2003). Assessing Program Fidelity and Adaptations: Toolkit. Employment Development Centre Inc. Retrieved February 5, 2017 from: http://www.promoteprevent.org/sites/www.promoteprevent.org/files/resources/FidelityAdaptationToolkit.pdf

- Engineers Without Borders. Failure Reports. Retrieved from http://legacy.ewb.ca/en/whoweare/accountable/ failure.html

- Fail Forward (2014). Fail Forward Toolkit. Retrieved from https://failforward.org/resources/#materials

- Family and Youth Services Bureau (2011, July 21). Presentation: Fidelity Monitoring and Program

Adaptation with Fidelity Monitoring Tip Sheet. US Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved February 5, 2017 from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/assets/fidelity-monitoring-20110721.pdf - Family and Youth Services Bureau. Fidelity Monitoring Tip Sheet. US Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved February 5, 2017 from: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fysb/prep

fidelity-monitoring-ts.pdf - Good, A. (2014, May 20). Intelligent Failure Learning & Innovation Loop. https://failforward.org/if-loop/

- Good, A. (2014, February 26). What is Intelligent Failure?. Retrieved from https://failforward.org/whatis-intelligentfailure/

- Government of Canada. (n.d.). Centre of Excellence for Evaluation: Theory-Based Approaches to Evaluation.

Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/audit-evaluation/centre excellence-evaluation/theory-based-approaches-evaluation-concepts-practices.html - Hammond, W., & Zimmerman, R. (2012). A strengths-based perspective. Resiliency Initiatives. Retrieved from http://www.resiliencyinitiatives.ca/cms/wpcontent/uploads/2013/03/STRENGTH_BASED_PERSPECTIVE-Dec-10-2012.pdf

- Harvard Business Review (2011, April). The Failure Issue. https://hbr.org/archive-toc/BR110

Imagine Canada. (n.d.).Project Evaluation Guide for Non-Profit Organizations: Fundamental Methods & Steps.

Retrieved from http://sectorsource.ca/sites/default/files/resources/files/projectguide_final.pdf - Multisystemic Therapy. (2017). What is Multisystemic Therapy?. Retrieved from http://mstservices.com/

- National Gang Center. (n.d.). About the OJJDP Comprehensive Gang Model. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgangcenter.gov/Comprehensive-Gang-Model/About

- Northwest Center for Public Health Practice. (n.d.). Data Collection Methods Toolkit. Retrieved from http://www.nwcphp.org/training/opportunities/online-courses/data-collection-for-program-evaluation

- O'Connor, C., et al. (2007). Program Fidelity and Adaptation: Meeting Local Needs Without Compromising Program Effectiveness. What Works, Wisconsin Research to Practice Series, 4. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin–Madison/Extension.

- Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child & Youth Mental Health. (n.d.). Program Evaluation Toolkit. Retrieved from http://www.excellenceforchildandyouth.ca/sites/default/files/docs/program-evaluation-toolkit.pdf

- Roebuck, B., Roebuck, M.A., & Roebuck, J. (2011). From Strength to Strength: A Manual to Inspire and Guide strength-based interventions with young people. Cornwall: Youth Now Intervention Services.

- Rogers, P.J., & Davidson, E.J. (2016). Genuine Evaluation. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://genuineevaluation.com/

- Savignac, J., & Dunbar, L. (2014). Guide on the Implementation of Evidence-Based Programs: What Do We Know So Far?. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

- Schwartz, M. (n.d.). Best practices in experiential learning. The Learning & Teaching Office, Ryerson University. Retrieved from http://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/lt/resources/handouts

/ExperientialLearningReport.pdf - Sitkin, S. B. (1992). Learning through failure: The strategy of small losses. Research in Organizational

Behavior, 14, 231-266. http://mujtama3i.org/wpcontent/uploads/2015/06/%D8%A7%D8% B6%D8% BA%D8 %B7-%D9%87%D9%86%D8%A73.pdf - Solomon, J., Card, J. J., & Malow, R. M. (2006). Adapting efficacious interventions: Advancing translational research in HIV prevention. Evaluation and the Health Professions, 29(2), 162-194.

- The National Implementation Research Network's Active Implementation Hub. (2013). The Hexagon Tool-

- Exploring Content. Retrieved from http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/resources/hexagon-tool-exploringcontext

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Making Adaptations Tip Sheet. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/fysb/prep-making-adaptations-ts.pdf

- Wabano Centre for Aboriginal Health (2016). Centre of Excellence: Wabano Model of Care. Retrieved from http://www.wabano.com/about/centre-ofexcellence/

Footnotes

- 1

This tool can be accessed at: http://implementation.fpg.unc.edu/sites/implementation.fpg.unc.edu/files/NIRN-TheHexagonTool.pdf

- Date modified: