Cyber Review Consultations Report

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- General Overview

- Detailed Findings

- Evolution of the Cyber Threat

- Increasing Economic Significance of Cyber Security

- Expanding Frontiers of Cyber Security

- Canada's Way Forward on Cyber Security

- Appendix A – Snapshot of Responses

- Appendix B – Stakeholder Say

- Appendix C – Consultation Questions

Prepared For: Public Safety Canada

Prepared By: Nielsen

January 17, 2017

Executive Summary

Background and Objectives

Consultation Background

The Canadian cyber security environment is evolving. Rapid changes to digital technology have far-reaching security, economic and social impacts. Recognizing that digital technology plays a central role in the everyday lives of Canadians, the Government of Canada wanted to hear the views of Canadians on this issue.

Objectives

As part of this review, the Government initiated and administered an online public consultation process that sought the views of Canadians, the private sector, academia, and other informed stakeholders on the cyber security landscape in Canada. Specifically, the objectives of this consultation were to:

- Provide an overview of cyber security trends and challenges;

- Outline a proposed way forward for cyber security in Canada; and

- Solicit responses on 18 questions.

Methodology

In total, 2005 submissions through the web portal and 90 position papers were submitted. When combined, those 2095 submissions contained 2,399 responses to individual questions across four main topics, as follows:

- Evolution of the Cyber Threat: 1,728 responses

- Increasing Economic Significance of Cyber Security: 364 responses

- Expanding Frontiers of Cyber Security: 190 responses

- Canada’s Way Forward on Cyber Security: 117 responses

Summary of Key Findings

The public consultation confirmed that cyber security in Canada is a highly complex issue with multiple challenges and an increasing range of opportunities. The responsibility for addressing these challenges and seize these opportunities is shared by governments, the private sector, law enforcement and the public.

Throughout the consultation, three ideas were consistently raised as being important and relevant to cyber security in Canada: privacy, collaboration, and using skilled cyber security personnel. Across the full range of consultation topics, participants stressed the need to uphold all Canadians’ privacy rights, the need for stakeholders to collaborate with one another (i.e., governments, private sector, law enforcement, academia, non-profit organizations), and the need to rely on cyber security experts.

In addition to these three ideas that permeated the results, the Government of Canada cyber security consultation yielded recommendations on specific areas for action, needs and means, and barriers and constraints. These findings are summarized below.

Areas for Action

Potential areas for action were identified through the consultation, including:

- Increase public education and awareness;

- Improve training for cyber security professionals and law enforcement;

- Develop and promote established standards, best practices, certification and legislation; and

- Increase funding and resources for all areas of cyber security.

Increase public education and awareness

Participants indicated that the public bears some responsibility for protecting themselves from cyber threats, while also acknowledging that awareness of the importance of cyber security and understanding of basic security measures is lacking among the general public.

Participants recommended that public education and awareness be developed to improve cyber security in Canada, build a 21st century knowledge base, strengthen consumer confidence in e-commerce, and increase public engagement. Recommendations for improving public education included developing a standard cyber security curriculum and to provide funding for education programs.

Better training for cyber security professionals and law enforcement

Participants emphasized the need for improved cyber security training in order to: address cybercrime and cyber threats in Canada; promote growth and innovation in the cyber security; and protect critical infrastructure. Improved public education and awareness were viewed as supporting this effort, especially if youth were educated in cyber security, as it would drive up the knowledge foundation. Recommendations for improving the training of cyber security professionals included developing a certification program and incentivizing training.

Law enforcement plays a key role in cyber security and the consultation revealed some consensus from participants that better training of law enforcement in cyber security was imperative. Without this training, participants indicated that policing in cyberspace would not be effective. Furthermore, a lack of specialized training feeds into concerns expressed over the infringement of privacy rights.

Standardization, best practices, certification and legislation

The consultation uncovered that developing standards, best practices, certification and legislation were proposed as ways to protect critical infrastructure, prevent advanced cyber attacks, improve the security of emerging technology, encourage growth and innovation, and increase public engagement.

Cyber security standards and legislation were also identified as a means to encourage adoption of improved cyber security regimes, including information sharing ith consequences for those who do not conform.

Increase funding and resources

A key action area uncovered by the consultation was the need to increase funding and resources in cyber security, as there was a general perception among participants that cyber security is underfunded and understaffed. Increasing funding and resources is particularly important to encourage the adoption of stronger security measures (i.e., encryption and VPNs), conducting audits and system tests, and incentivizing better practices in cyber security.

Means

The consultation revealed additional potential means to address cyber security issues in Canada. These included:

- Conducting regular audits and system security tests;

- Using strong cyber security measures, especially encryption and VPNs;

- Being transparent and including public oversight; and

- Being proactive.

Audits and systems testing

Participants suggested that conducting regular audits and tests of security systems would help to protect critical infrastructure and prevent advanced cyber attacks.

Strong cyber security measures

Use of stronger security measures – like the most commonly mentioned measures of encryption and VPNs – would help to protect against advanced cyber threats and improve the security of technology.

Transparency and public oversight

In order to ease concerns over privacy and to increase public engagement, participants cited a need for more transparency from law enforcement, government, and to a lesser extent, the private sector. This transparency would allow for more public oversight and accountability. Transparency by law enforcement might also help to improve negative perceptions of policing in cyberspace and lack of faith in law enforcement.

Being proactive

There was some consensus among participants that in order to improve cyber security in Canada, to effectively police in cyberspace, and to protect against advanced cyber threats, a focus needs to be placed on prevention: actions taken need to be proactive in nature.

Constraints and Barriers

Participants also recognized a number of barriers and constraints affecting cyber security in Canada, including:

- A reluctance to share information with the public and competitors;

- Lack of incentives and repercussions for not improving ones cyber security;

- Costs associated with strengthening cyber security;

- Lack of faith in law enforcement; and

- No clear channel to report cybercrime, threats, incidents or attacks.

Reluctance to share information

Despite the fact that many participants cited the need for information sharing to improve cyber security in Canada, the reluctance to share information about one’s cyber vulnerabilities, incidents and attacks makes it a significant barrier. There was little consensus on the reasons behind this reluctance; participants referred to the fear of creating more vulnerabilities, fear of brand image and reputation damage, and fear of giving others a competitive edge.

No incentives and no repercussions

Despite consensus on the need to adopt stronger cyber security measures, the consultation revealed that there are no meaningful incentives in place for doing so (e.g., tax credits) or repercussions for those who do not (e.g., prosecution). Participants called for more incentives and stronger consequences, as well as additional funding (e.g., budgetary appropriation) or legislation as a means to overcome this barrier.

Costs

The cost of adopting stronger cyber security measures is a significant barrier for businesses, organizations and individuals. As long as strong cyber security measures continue to significantly affect the “bottom line“, it will continue to be a considerable barrier. This barrier is compounded if there are no financial repercussions for not conforming to established cyber security standards.

Concern over capacity in law enforcement

The consultation uncovered a lack of faith in law enforcement. While many participants were sympathetic of the challenges of policing in cyberspace (e.g. difficult to pinpoint a cybercriminal, jurisdictional complexity), there are perceptions that members of law enforcement lack training for investigating cybercrimes and are ineffective in preventing and prosecuting them. Additionally, many participants conveyed concern that policing in cyberspace infringes on their privacy rights, especially with regard to blanketed surveillance. Participants pointed to improved cyber training for members of law enforcement, as well as greater transparency and public oversight.

No clear reporting channel

There was a perception among participants that there is no clear channel to report cybercrime, threats, incidents or attacks. This relates to the previous barrier; without an understanding of who, where and how to report cybercrime, the threats, incidents and attacks cannot be addressed.

General Overview

Background & Objectives

Consultation Background

The Canadian cyber security environment is evolving. Rapid changes to digital technology have far-reaching security, economic and social impacts. Recognizing that digital technology plays a central role in the everyday lives of Canadians, the Government of Canada wanted to hear the views of Canadians on this issue.

Objectives

As part of this review, the Government initiated and administered an online public consultation process to seek the views of Canadians, the private sector, academia, and other informed stakeholders on the cyber security landscape in Canada. Specifically, the objectives of this consultation were to:

- Provide an overview of cyber security trends and challenges;

- Outline a proposed way forward for cyber security in Canada; and

- Solicit responses on 18 questions.

Methodology

Overview

Participation in the consultation was voluntary. Questions were asked for information gathering purposes only. Any reporting of data and analysis based on submissions is aggregated or anonymized. Raw data may be released online; however, any personal identifying information will be removed prior to disclosure. All information collected was be handled in accordance with the Privacy Act.

Findings are not statistically projectable to a broader population and no estimates of sampling error can be calculated.

In total, 2005 submissions through the web portal and 90 position papers were submitted. When combined, those 2095 submissions contained 2,399 responses to individual questions across four main topics, as follows:

- Evolution of the Cyber Threat: 1,728 responses

- Increasing Economic Significance of Cyber Security: 364 responses

- Expanding Frontiers of Cyber Security: 190 responses

- Canada’s Way Forward on Cyber Security: 117 responses

A breakdown of the responses by region and category has been included in Appendix A.

Consultation Design

Public Safety Canada led the design of the questions and it was offered in both official languages. All questions were open-ended in nature, and participants were able to respond to some or all questions, as they saw fit.

A complete list of sub-theme questions has been provided in Appendix B.

Consultation Administration

Canadians and key cyber security stakeholders were invited to participate in the voluntary consultation from August 16 to October 15, 2016. The questions were posted on the Government of Canada’s website and some participants opted to provide their responses through email submissions. Some of the email submissions were received after the closing date of October 15, but have been included in this analysis.

Data Analysis

Public Safety Canada provided Nielsen with the responses to the consultation. Nielsen combined the data and reviewed the file to ensure all data received was valid.

Nielsen’s coding team read and classified each of the responses into common themes, assigning each response a specific code so it could be analyzed in aggregate. Nielsen’s team read through all the comments and ensured all codes were assigned properly. Nielsen then compared the qualitative results based on the category of participant.

The four types of participants explored further in this report are: Engaged Citizens, Government, Cyber Security Industry and Other Industry (e.g., law enforcement, financial, health). Participants from other categories (i.e., Academics and Students) have been represented in the overall results, but have not been presented on their own due to a limited number of participants (especially Academics), and/or the lack of consistency and distinctness of the responses (especially Students). Further, some participants chose to remain anonymous.

An effort was taken to analyze the data based on the region of the participant, however, analysis revealed that the participants were not evenly distributed across Canada, and therefore, regional differences were more so determined by the category of participant and not actually due to their location of residence.

Important Notes Regarding the Consultation Approach

The decision to conduct an online public consultation maximized the opportunity for Canadians across the nation to participate. There are some implications inherent to online public consultations that should be taken into account when reading this report.

- While the data has been checked to detect multiple submissions from an individual, it is still possible that the data may include multiple responses from the same participant.

- Some submissions received represent the collective feedback of a group of individuals (e.g. submission from a professional association).

- Given that no quotas to balance the composition of the sample were set, and that those participating opted to provide their opinion based on their levels of awareness, engagement, and personal interest, the results cannot be interpreted as being representative of the Canadian population.

- No sampling margin of error or statistical inferences can be calculated on the data of this public consultation.

- The questionnaire included only open-ended questions where participants could express their opinions and views. As a result, many of the responses provided do not directly address the topic presented in each question.

- The consultation provided no follow-up questions or way of inquiring with participants how they felt about additional ideas or suggestions. Therefore, the depth of information gathered is sometimes limited.

- Many of the questions offered examples of possible responses in order to clarify the question. While this served an important purpose given the limited direction available to participants, it also creates some bias to the responses by way of potentially leading participants.

Taking this information into account, the reader of this report should note the following:

- Ranking words (e.g., all, some, few, top mention) have been used to show the magnitude of opinions received, but should not be interpreted as being representative of the total population.

- Responses have been reported by theme and not necessarily by question.

- The report includes some verbatim responses to highlight the qualitative nature of the research and have been selected to provide additional context.

- Participants appeared to use the terms “public sector” and “government” interchangeably. Because the consultation did not provide the opportunity to ask for clarification, it is hard to know with certainty whether a participant was referring to the government when they said public sector, though in many cases it does appear that way.

- Similarly, it is difficult to ascertain whether participants were referring to the Government of Canada specifically when they said “government,” and few cited the Government of Canada outright.

- Collaboration with “strategic partners” was a common theme throughout the consultation, however, the specific partners cited by participants often varied and included: non-profits, private entities, other nations, other governmental departments and academia.

Disclaimer

This analysis of the online consultation results was conducted by ACNielsen Company of Canada. The purpose of this analysis was to provide Public Safety Canada with a better understanding of the views and opinions of participants. While all care has been taken in preparing this report and summarizing the findings as accurately as possible, the report provides only a subjective review of the responses. Questions were completed on a voluntary basis, responses may have been incomplete and interpretation of the responses may vary. ACNielsen Company of Canada expressly disclaims any liability for any damage resulting from the use of material contained in this summary.

Detailed Findings

The findings in this report have been organized by trend in keeping with the method in which responses were gathered from participants. As mentioned, the four trends are: Evolution of the Cyber Threat; Increasing Economic Significance of Cyber Security; Expanding Frontiers of Cyber Security; and Canada’s Way Forward on Cyber Security. Each of these trends have been introduced with the same content provided in the workbook for participants to provide a clear understanding of the topic in advance of the consultation findings.

When a divergence of views by the type of participant occurred in the consultation (i.e., Engaged Citizens, Government, Cyber Security Industry, and Industry), those differences have been outlined. When it has not been clearly indicated, no significant differences were apparent, which may suggest some consensus.

Evolution of the Cyber Threat

The growth of the internet, digital networks and use of mobile devices by individuals, governments and businesses has been matched by the growth of threats in cyberspace. Cyber capabilities that were once rare and expensive have become commonplace and affordable. As a result, a growing number of nation-states are attempting to establish their presence in the cyber domain. Non-state actors are also developing cyber capabilities, and while they often lack the sophistication and resources of nation-states, they can nevertheless be effective in conducting malicious cyber operations and in committing cybercrime. To complicate matters further, unlike in the physical world, it is challenging to identify the origin and purpose of cyber attacks. These factors contribute to a growing cyber threat facing Canada.

Addressing Cybercrime

The workbook outlined to participants how cybercrime falls into two categories: traditional criminal activities that leverage technology as a tool, and cybercrime that targets technology itself. It explained that cybercrime is transnational and requires significant cooperation across borders to address. The workbook also summarized the challenges faced by law enforcement as: the accelerating pace of incidents, the complexity of technology, and the increasing need to obtain intelligible digital evidence.

Participants were asked how law enforcement can better address the challenges posed by cybercrime, how public and private sectors can protect themselves from cybercrime, and what barriers (if any) exist to reporting cybercrime to law enforcement agencies.

The overarching discovery within this theme is that cybercrime is a complex challenge that cannot be addressed by a single party or solution. The public, governments, the private sector, law enforcement, skilled personnel and strategic partners all need to play a part.

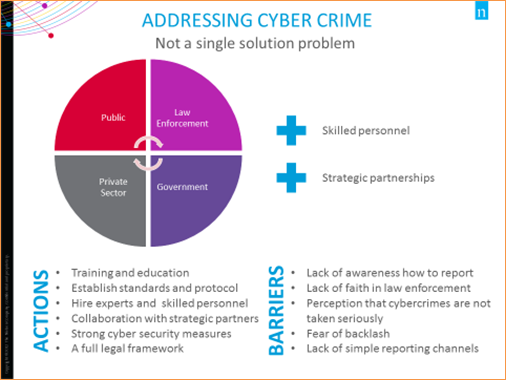

Image Description

This visual is displaying a pie chart that illustrates the four groups that need to work together to address cybercrime: the public, law enforcement, the private sector, and Government. Key elements to support this work include the development and increased need for skilled personnel, and the building of strategic partnerships. It also includes a list of actions and a list of barriers to addressing cybercrime, which are as follows:

Actions:

- Training and education

- Establish standards and protocol

- Hire experts and skilled personnel

- Collaboration with strategic partners

- Strong cyber security measures

- A full legal framework

Barriers:

- Lack of awareness how to report

- Lack of faith in law enforcement

- Perception that cybercrimes are not taken seriously

- Fear of backlash

- Lack of simple reporting channels

Action Areas

The recommendations identified by participants in this section of the consultation were:

- Enhancing training and education (for law enforcement, cyber security personnel, and the public);

- Establishing standards, protocols and best practices, for businesses and individuals alike, that are clear and easy to follow;

- Using dedicated experts and skilled personnel;

- Collaborating with strategic partners;

- Using stronger cyber security measures (like encryption, virtual private networks (VPNs), and not USBs);

- Developing a legal framework in which law enforcement can operate.

As the following sections will show, these recommendations do not apply to every cyber security stakeholder group (i.e., law enforcement, government, private sector and the public).

Law Enforcement’s Role

When participants were asked how law enforcement could better address the growing challenge posed by cybercrime, the top mention was through the collaboration with strategic partners.

“The type of human and technical resources required to intervene and enforce the law in cyberspace cannot be the same as in the real world.”

The need for additional training was mentioned by many participants, along with hiring skilled personnel and cyber security experts. This suggests that many participants do not believe that law enforcement currently has the capacity to take the lead in this area.

In regards to law enforcement, many participants expressed concern over their privacy and how measures to address cybercrime (e.g., surveillance) could undermine these rights. Many participants thought that there should be more transparency and public outreach.

Some participants called for more funding, adoption of better technology and a focus on capacity building for law enforcement.

“We emphasize on [sic] prevention because of the difficulties involved in reacting to cybercrime.”

Additionally, a focus on proactive and preventative measures to cybercrime was important to participants.

Government’s Role

“The Government of Canada can provide much needed leadership by creating, adopting and modeling best practices for cyber security, and making efforts to transfer this knowledge to the private sector.”

Many participants thought that government should share information between agencies and work with the private sector and other strategic partners (e.g., other nation-states, non-profits, academia).

The need for more funding and resources to be allocated to cybercrime efforts (e.g., budgetary appropriation) was cited by many participants. There were also suggestions that government offer incentives and tax credits to encourage best practices, especially within the private sector.

Many participants also said that government needs to hire skilled personnel and use strong cyber security measures (e.g., encryption, VPNs).

Some participants indicated that government should demonstrate greater leadership on addressing cybercrime, while some thought that it should just support the effort. A few participants indicated that they did not think government should be involved at all.

A few participants suggested that government needed to update current legislation around cybercrime and cyber security, as well as design a legal framework for cybercrime. Most participants who indicated a need for legislation and legal frameworks did not provide the specifics of their suggestions.

Private Sector’s Role

There was a common perception that the private sector does not take the threat of cybercrime seriously, due, at least in part to the perceived negative impact on their “bottom line”.

Many participants stated that the private sector needs to work with government, as well as other strategic partners. And again, it was stated that the private sector needs to hire skilled personnel to manage and implement strong cyber security measures.

Many stated that businesses need to be held accountable when they do not protect the data they collect from the public.

Ways to Protect Against Cyber Threats

Participants cited some specific ways that government and the private sector could protect themselves from cybercrime, such as: adopting stronger security measures (e.g., encryption, VPNs), increasing monitoring of their systems, conducting system audits, and consistently patching their systems.

The Public’s Role

While the public’s role was not at the forefront of responses to this section of the consultation, many participants indicated that the public shares in the responsibility of addressing cybercrime. This includes responsibilities to be informed about the seriousness of cyber security and to be educated about how to protect against cyber threats. It also includes the public’s role to exercise vigilance and common sense when using technology.

Some participants explicitly stated that the onus is on all members of the public to protect themselves from cyber threats.

Reporting Barriers

When participants were asked to provide likely barriers to reporting cybercrimes, the top barrier cited was a lack of awareness of where, how and to whom cybercrime should be reported. Many pointed to an absence of a simple reporting channel.

Many participants perceived flaws with how law enforcement deals with cybercrime and felt that that cybercrime is not taken seriously enough by law enforcement. Many cited poor conviction rates for crimes conducted in cyberspace. Some participants were sympathetic to the challenges law enforcement face when investigating cybercrime (e.g., difficulty determining the location and identity of cyber criminals, lack of special training), while also sharing in the view that there are few convictions.

Some believed that potential reputation loss and a damaged brand was at the core of reporting barriers, in addition to fear of liability. Cyber Security Industry participants were more likely to identify these issues as barriers.

Other Industry participants were less likely to name fears of liability, shame and embarrassment, and reputation loss as barriers, but were more likely to say that the lack of legislation and regulation requiring reporting were the obstacles at play.

A few participants expressed that there were no reporting barriers present.

Policing in Cyberspace

The questions for participants concerning policing in cyberspace were prefaced by a description of the current landscape and challenges faced by law enforcement. It confirmed that police in Canada are mandated to investigate criminal activity in both the online and physical worlds, and acknowledged that the expectations of law enforcement in the cyber world are not as well understood and agreed upon by Canadians. The workbook indicated that the effectiveness of existing police tools and authorities are being challenged by technological advancements, as well as changes in law and court decisions. In turn, the same factors are shaping Canadians’ expectations of how police should operate in an online world.

Participants were then asked to state their expectations for policing in cyberspace and explain how they are different from policing in the physical world. They were also asked how cybercrime can be addressed in a manner that respects Canadians’ privacy rights and protects public safety.

“In principle, my expectations are the same. If a crime is committed, I expect it to be investigated.”

Overall, the most common opinion was that policing in cyberspace should provide equal protection, while upholding the same standards, as in the physical world.

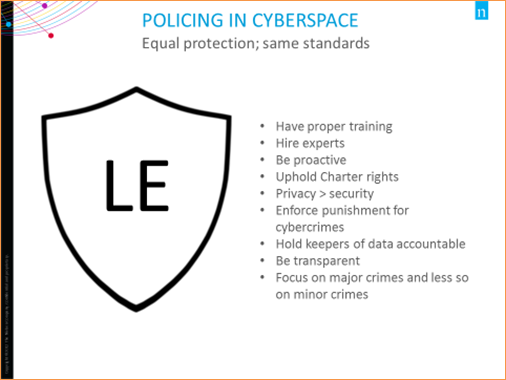

Image Description

This visual displays a shield with the initials “LE” in the middle, which stands for Law Enforcement. This shield represents the different elements that Canadians believe are important for policing in cyberspace. This includes ensuring equal protection of their privacy rights and personal information while applying the same investigative standards as traditional crime when investigating cybercrime.

These elements are: Having proper training, hiring experts, being proactive, upholding Charter rights, prioritizing privacy over security, enforcing punishment for cybercrimes, holding keepers of data accountable, being transparent, and focusing on major crimes and less so on minor crimes.

Participant Expectations Of Law Enforcement

Many shared the opinion that cybercrime should not be treated any differently than crime in the physical world. They also expressed the view that law enforcement must adhere to the same standards when investigating cybercrime as they do traditional crime. That includes obtaining necessary warrants, not investigating individuals without a reasonable cause, and upholding the principle of the presumption of innocence.

“This means no searching private property (phones and computers) without a warrant. This includes police and border agents demanding passwords and threatening arrest.”

The view of many participants was that Canadians’ privacy rights protected under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms need to be upheld by law enforcement at all times and many expressed concern that those rights would be breached by methods of policing in cyberspace (e.g. surveillance). That concern likely led some participants to cite the need for more transparency and public oversight of law enforcement.

Many participants shared the opinion that policing cybercrime is much more difficult than policing other crimes. It was mentioned that cybercrime is borderless, and does not necessarily take place from within Canada; and that cyber criminals are much more difficult to identify. Government and Cyber Security Industry participants were more likely to share this idea than others.

Appropriate and increased levels of funding and resources to address cybercrime by law enforcement were also mentioned by participants. Many indicated that those resources should be used to hire experts in the field, or that collaboration with strategic partners was necessary. While some believed that those experts or partners should be civilian, others indicated that existing officers should be trained in cybercrime enforcement.

Many participants thought that law enforcement needed to be proactive and have a greater presence online.

For some participants, expectations of law enforcement’s ability to address cybercrime were low due to the perception that most cybercrime is rarely prosecuted.

“To police cyberspace does not require the installation of military-grade intrusion software at the carrier level and below to troll the entire population for subjectively 'suspicious' keywords. Such tactics are based upon junk science. What it requires is a truly educated policing element that knows how to deploy targeted tools with sophistication and stealth in order to make an arrest.”

A few participants suggested that Canada’s legal framework needs to be updated to better address cybercrime.

A few Other Industry participants thought that law enforcement required greater care (e.g., using skilled investigators and specialized methods) to investigate cybercrime.

Managing Security and Privacy

Many participants, especially Engaged Citizens and Cyber Security Industry participants, explicitly stated that privacy must trump security. These participants expressed a great deal of concern that overreaching surveillance by law enforcement was infringing on Canadian’s privacy rights. Many participants indicated a need for more accountability, transparency and oversight for law enforcement.

Government participants were less likely to express the same concerns over privacy, but instead were more likely to cite a need for legal frameworks to uphold privacy rights and prosecute cybercriminals.

Many participants believed that punishments for cybercrime need to be enforced, and that keepers of data (e.g., businesses) need to be held accountable when they do not protect that information. This idea was more likely to be expressed by Engaged Citizens.

“Privacy and security are not a zero-sum game and we can have both. There is no security without privacy. And liberty requires both security and privacy. The famous quote attributed to Benjamin Franklin reads: "Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety, deserve neither liberty nor safety." It's also true that those who would give up privacy for security are likely to end up with neither.”

Another common response given by participants was that security and privacy could both be managed through the use of stronger security measures, like encryption and VPNs.

Protecting Against Advanced Cyber Threats

Participants were introduced to this consultation topic with a statement that public institutions and Canadian companies are the targets of persistent, well-funded and sophisticated cyber attacks, by both states and non-states. Countries are committing espionage to obtain information for negotiations, military plans, intellectual property and business strategies for their own competitive edge. They are also developing cyber tools to threaten the computer systems that run critical infrastructure – a common target for non-state actors as well.

Participants were then asked to identify what is needed to protect against advanced cyber threats and possible constraints on information sharing.

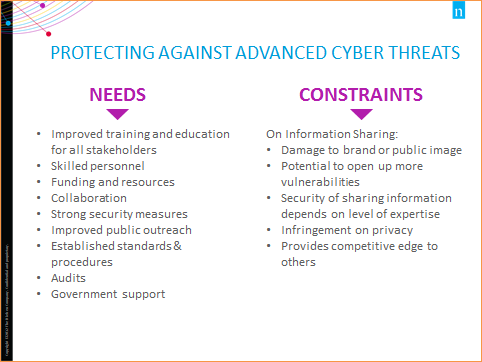

Image Description

This visual displays a list of what is needed to protect against advanced cyber threats and a list of possible constraints on information sharing. They are as follows:

Needs:

- Improved training and education for all stakeholders

- Skilled personnel

- Funding and resources

- Collaboration

- Strong security measures

- Improved public outreach

- Established standards and procedures

- Audits

- Government support

Constraints on Information sharing:

- Damage to brand or public image

- Potential to open up more vulnerabilities

- Security of sharing information depends on level of expertise

- Infringement on privacy

- Provides competitive edge to others

Protection Needs

“We need people to be trained to become experts in delivering cyber defense training, and industries must take this seriously.”

The top mention among participants was the need for better training, for law enforcement and IT personnel in particular. Another common response was the need for hiring skilled personnel or to consult with cyber security experts as needed.

Participants also provided the following examples of ways to protect against advanced cyber threats:

- Increasing funding and resources;

- Collaborating with strategic partners;

- Using strong security measures;

- Establishing standards and procedures;

- Improving public outreach and education;

- Conducting audits and security tests; and

- Enhancing government support.

Government participants were more likely to recommend increased funding and resources; increased public outreach; improved training; increased and consistent patching of systems; consistent and strict monitoring; and being proactive and focusing on risk management.

Cyber Security Industry participants were significantly more likely to indicate the need for collaboration with strategic partners, and increasing audits and security tests.

Information Sharing Constraints

The most common response among participants was that information sharing is of utmost importance, yet many participants also mentioned that one’s brand or public image could be damaged; that information sharing could open up more vulnerabilities; that the security of information sharing depended on the level of training of those doing the sharing; and that sharing information gives a competitive edge to others.

“Embarrassment, reputation damage and bottom line impact. I share with my friends and colleagues across the country often because we know each other and have a level of trust. They help me and I help them, we look out for one another. When that notion gets elevated to the presidents' offices of the world, they want to clam up in fear of losing competitive advantage etc.”

Some participants expressed concern that their privacy rights may be breached through information sharing.

Other shared responses among participants were:

- Information should not be shared without adherence to regulations and applicable laws;

- Importance of patching vulnerabilities;

- Fear of liability and legal repercussions;

- Delay the release of information until a solution is in place;

- Importance of legislation and enforcement;

- Sharing is hindered by concern for profits;

- Sharing is hindered by insufficient capacity;

- Only non-sensitive information should be shared; and

- Fear of shame and embarrassment.

A few participants did not see any constraints on information sharing.

Government participants were more likely to state that potential damage to brand and public confidence was a barrier, as well as profit loss.

Cyber Security Industry participants were more likely to suggest that sharing information gives others a competitive edge and to see profit loss and damage to brand and public confidence as barriers. They were less likely to say that sharing information opens up more vulnerabilities.

Other Industry participants were also less likely to cite an increase in vulnerability due to information sharing; however, they were more likely to believe that the security of sharing information depends on one’s level of training and expertise and to suggest that sharing information gives others a competitive edge.

Engaged Citizens were more likely to state that information sharing could infringe on privacy rights and that any action taken should be done in accordance with those rights.

Increasing Public Engagement

The preface to the questions for participants regarding increasing public engagement clearly stated that Canadians need to know how to protect themselves from cyber threats and that deeper engagement in cyber security is needed from all parts of society.

Participants were then asked how individuals can be better informed about how to recognize and react to cybercrime, and in what ways public and private sectors can facilitate better public awareness of cyber security issues.

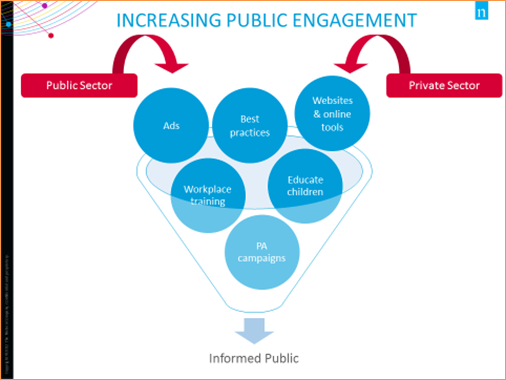

Image Description

This image is entitled “Increasing Public Engagement” and illustrates a funnel in which elements from both the public and private sector are flowing through together to create an informed public. These elements are: Ads, best practices, websites & online tools, workplace training, educate children, and public awareness campaigns.

Working Together to Increase Awareness and Educate the General Public

To engage the public, and ultimately increase awareness and education of cyber security issues, participants offered the following approaches for government and private sector to take:

- Run public awareness campaigns;

- Offer workplace training;

- Create advertising, both conventional and on social media;

- Develop and provide online resources and tools;

- Begin with educating children in the public school system;

- Develop and promote best practices (that are clear and unified);

- Conduct information sessions and workshops; and

- Collaborate with strategic partners.

Many participants believed that the public had a level of responsibility in ensuring they were educated, and some mentioned that common sense needed to be exercised by those who use digital technologies.

Instead of creating a more engaged public, some participants believed that the private sector and government should be the focus for improving cyber security.

Government participants were more likely to suggest the use of public awareness campaigns and identify the need for clear and concise information available to the public. Government participants were less likely to suggest using advertising or the need to develop and promote best practices.

Other Industry participants were more likely to cite a need for best practices and suggest the use of advertising to educate the public. Engaged Citizens were also more likely to suggest the use of advertisements.

Cyber Security Industry participants were more likely to express having more government engagement and focusing efforts on the private sector (including conducting more testing of systems). Likewise, Engaged Citizens were also more likely to place a focus on the private sector.

Increasing Economic Significance of Cyber Security

Digital technologies and the internet are increasingly important enablers of innovation and economic growth.

At the same time, cyber security can improve Canada’s competitiveness, economic stability, and long-term prosperity. There is an opportunity for Canada to carve out a competitive advantage in cyber security and create a robust, secure, leading-edge digital economy.

Strengthening Consumer Confidence in E-Commerce

The workbook laid out to participants that Canadians need to be able to trust the security of transactions online to safeguard consumer confidence and boost the economy through continued engagement in the e-marketplace. The workbook also outlined that many businesses either do not realize that they could be targeted by cyber criminals or find it hard to identify affordable and effective solutions to secure their information.

Participants were asked how businesses could be encouraged to adopt better cyber security regimes and what factors are important when assessing whether businesses online are secure.

Image Description

This visual displays four elements that encourage businesses to adopt better security regimes in order to strengthen consumer confidence in e-commerce. The four elements are: Laws and legislation; Incentives and tax credits; Education and awareness; Certification and established standards.

Encouraging the Adoption of Better Cyber Security Regimes

“Introduce optional certification for businesses and individuals. Depending on level, participating members may have to pass cyber-security exam, implement best practices, or even report their internet traffic to the police.”

When asked what could be done to encourage businesses to adopt better cyber security regimes, most responses from participants centered on four main ideas:

- Create laws and legislation;

- Provide incentives or tax credits;

- Promote education and awareness; and

- Develop certifications and standards.

Some participants suggested that businesses should collaborate with strategic partners and conduct security audits and testing.

Cyber Security Industry participants were more likely to recommend laws and legislation; and combined with Other Industry participants, they were also more likely to suggest education and awareness, as well as certification and standards.

While Government participants were less likely to suggest offering incentives and tax credits to encourage businesses, they were more likely to say that certification and established standards would achieve this goal.

Engaged Citizens were less likely to cite laws and legislation as ways to encourage businesses.

Important Factors to Consider

By far, the most common factor cited in assessing the security of a website by participants was the inclusion of “HTTPS” at the beginning of web addresses.

The reputation of the company was also cited as an important factor for many participants; however, few Engaged Citizens provided that response.

Data encryption and use of secured channels were also cited by participants as tactics for assessing security levels, especially for Other Industry participants. Few Other Industry participants and Engaged Citizens mentioned security logos or certification stamps, despite it being an otherwise common mention.

“Secure logos do not mean much, and [SSL] (https) could still be prone to man in the middle attacks. There is no way to be 100% safe.”

Some participants thought that people need to be more skeptical about the security of websites. For instance, it was stated that there are ways for websites to look secure, even if they are not. Government participants, especially, were more likely to think that people should exercise caution when assessing a website’s claims of security.

Additionally, the following factors to consider were mentioned in a few participant responses:

- Strong passwords;

- SSL/TLS certification;

- Multifactor authentication;

- Use of biometrics;

- Independent assessments of the website; and

- Listing of the company’s phone number and address.

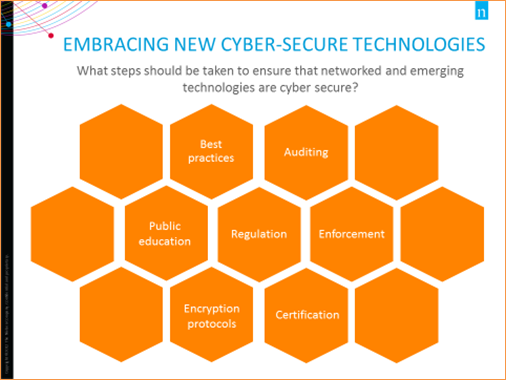

Embracing New Cyber-Secure Technologies

As an introduction to the questions for participants, the workbook summarized that while intelligent networked devices continue to be embraced by Canadians, there are no clear standards to secure these devices and ensure the privacy of the data they collect. It also described a potential barrier that implementing standards could make it harder for Canadian companies to bring out new products, or delay the introduction of products to Canadians.

With that in mind, participants were asked what steps should be taken to ensure that networked and emerging technologies are cyber secure.

Image Description

This image lists different steps that should be taken to ensure that networked and emerging technologies are cyber secure. These steps are: best practices; auditing, public education; regulation; enforcement; encryption protocols; certification.

Steps to Take to Ensure Cyber security

When participants were asked what steps should be taken to ensure the cyber security of new and emerging technologies, the most common response among participants was to establish clear standards and best practices. Many participants expressed the need for regulation and enforcement to hold product and service developers and manufacturers accountable. While these ideas were commonly shared, Other Industry participants were more likely to mention both.

Many participants mentioned the need for increasing public education, following encryption protocols, auditing servers and technology, and developing and mandating certification standards to secure new technologies.

Cyber Security Industry participants stood out for being more likely to suggest the use of auditing, certification, regulation and enforcement to secure networked and emerging technologies than other participants.

Other Views

“There is a primary responsibility on an individual to ensure installed applications are verified via a recognized repository.”

Some participants thought that the public needed to ensure their own protection, and have an understanding that there are risks associated with using their devices (especially on open and unsecured networks).

Another suggestion mentioned by a few participants was to avoid using default settings on their devices.

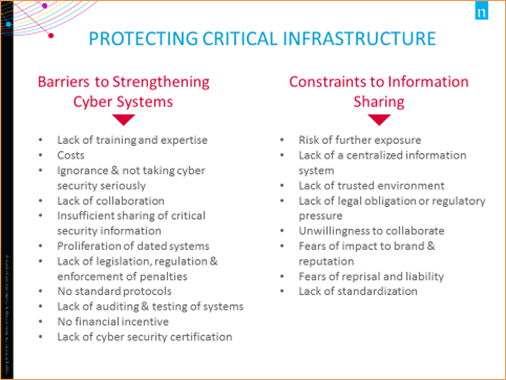

Protecting Critical Infrastructure

The introduction to the questions concerning protecting critical infrastructure for participants outlined how key improvements to critical infrastructure through the adoption of digital technologies and networked systems has opened up a vulnerability to be exploited by parties interested in theft, espionage and sabotage. It stated that despite much of Canada’s critical infrastructure being owned by the private sector, the Government of Canada will need to find ways to bring together other levels of government with those owners and operators to truly address threats to essential services.

Participants were then asked to weigh in on how to protect critical infrastructure by identifying the barriers to strengthening cyber systems and the constraints on information sharing and engagement.

Image Description

This visual lists the barriers to strengthening cyber systems and the constraints to information sharing that have an impact on protecting critical infrastructure:

Barriers to Strengthening Cyber Systems:

- Lack of training and expertise

- Costs

- Ignorance and not taking cyber security seriously

- Lack of collaboration

- Insufficient sharing of critical security information

- Proliferation of dated systems

- Lack of legislation, regulation and enforcement of penalties

- No standard protocols

- Lack of auditing and testing of systems

- No financial incentive

- Lack of cyber security certification

Constraints to Information Sharing:

- Risk of further exposure

- Lack of a centralized information system

- Lack of trusted environment

- Lack of legal obligation or regulatory pressure

- Unwillingness to collaborate

- Fears of impact to brand and reputation

- Fears of reprisal and liability

- Lack of standardization

Barriers to strengthening Cyber Systems

The common barriers to strengthening cyber systems identified by participants were:

- Lack of training and expertise;

- Costs (e.g., “Lack of properly tested products, and first to market for lowest cost is what is generating this issue”);

- Ignorance and not taking cyber security seriously;

- Lack of collaboration;

- Insufficient sharing of critical security information;

- Proliferation of dated systems;

- Lack of legislation, regulation and enforcement of penalties;

- No standard protocols;

- Lack of auditing and testing of systems;

- No financial incentive; and

- Lack of approach to award cyber security certification.

Constraints to Information Sharing and Engagement

The common constraints to information sharing and engagement identified by participants were:

- Risk of further exposure (to criminals and competitors);

- Lack of a centralized information system;

- Lack of trusted environment;

- Lack of legal obligation or regulatory pressure;

- Unwillingness to collaborate;

- Fears of impact to brand and reputation (i.e., “Politics, public image, disregard of importance”);

- Fears of reprisal and liability; and

- Lack of standardization.

Expanding Frontiers of Cyber Security

Since Canada’s Cyber Security Strategy launched in 2010, emerging technologies have played a significant role in changing the digital landscape. In this new reality, cyber security must evolve at the same rate as new technologies.

Canada must be positioned to maintain an agile and adaptive cyber security posture as it pursues new opportunities and develops and adopts key technologies and capabilities.

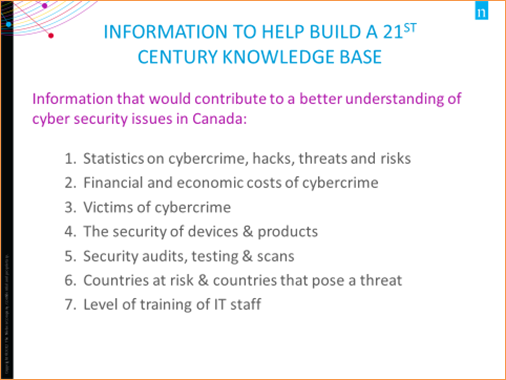

Building a 21st Century Knowledge Base

The workbook outlined to participants that Canada needs better information on cyber security issues in order to provide a more accurate view of cyber security issues, to confront cyber security threats and to identify opportunities related to cyber security. The workbook identified that this information could then be used by academics, researchers and policy-makers to understand trends and to drive the development of new policies, programs and services.

Participants were asked to identify what information would contribute to a better understanding of cyber security issues in Canada.

Image Description

This visual shows a list of seven different types of information that would help build a 21st century knowledge base in the area of cyber security and contribute to a better understanding of cyber security issues in Canada. They are: 1) Statistics on cybercrime, hacks, threats and risks; 2) Financial and economic costs of cybercrime; 3) Victims of cybercrime; 4) The security of devices and products; 5) Security audits, testing and scans; 6) Countries at risk and countries that pose a threat; 7) Level of training of IT staff.

Information to Support an Increase in Understanding

“Few appreciate the strategic relevance of cyber security intelligence. You can’t manage what you don’t measure.”

Ranked by frequency of response, the following suggestions were given when asked what information would contribute to a better understanding of cyber security issues in Canada:

- Statistics on cybercrime, hacks, threats and risks (e.g., the frequency and timing, where they are occurring, the impact);

- Financial and economic costs of cybercrime;

- Victims of cybercrime;

- The security of devices and products;

- Security audits, testing and vulnerability scans;

- Countries at risk and countries that pose a threat; and

- Level of training of IT staff.

Even though it was not explicitly asked, the general sentiment around the collection and publication of this kind of information appeared to be favourable.

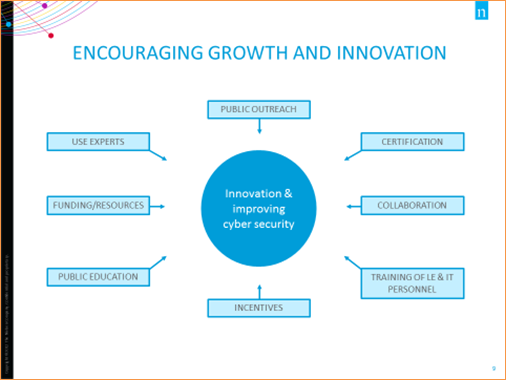

Encouraging Growth and Innovation

To preface the consultation questions, participants were informed that Canada needs to foster a robust cyber security workforce, as well as centres for leading-edge cyber security technology in order to encourage growth and innovation in cyber security, and to continue to reap the benefits of the digital global economy.

With that in mind, participants were asked what measures could be taken to improve the availability, relevance and quality of cyber security training, and what is needed to improve Canadian innovation in cyber security.

Participants gave many of the same ideas for both questions.

Image Description

This web chart displays different elements that can encourage growth and innovation. The main goal, displayed as a circle in the middle chart, is Innovation and improving cyber security. The eight elements that stem from this idea are displayed each in individual boxes outside the circle but point towards it. These are: use experts, public outreach, certification, collaboration, training of law enforcement and IT personnel, incentives, public education, and funding and resources.

Improving Canadian Innovation in Cyber Security

The top mention by participants when asked how to improve cyber security innovation was improving public knowledge and cyber literacy.

“Awareness will drive innovation”

Collaboration with strategic partners was another common solution, as well as having enough funding and resources.

Some participants thought that incentives and tax credits, consulting and hiring experts, or improving the training of law enforcement and IT personnel would drive innovation.

“The most important thing is to ensure that researchers are able to do their work without worrying about being sued by upset companies. In the US, there are many examples of papers being withheld and of research not being done because of the threat of lawsuits by device manufacturers or content owners. We need to ensure that the legal situation in Canada is very clear that research into security vulnerabilities will not lead to researchers being sued, even if (especially if) that research leads to vulnerabilities being discovered and publicised.”

In response to the consultation, a few participants offered their opinion that lawsuit threats and stringent copyright laws restrict creativity and innovation.

Improving the Availability, Relevance, and Quality of Cyber Security Training

Many of the same ideas to help drive Canadian innovation in cyber security listed above were offered to improve cyber security training, and to a greater extent, cyber security in general.

The most common response was that curricula must be developed in order to improve cyber security training.

Another common response was that the training of law enforcement and IT personnel needed to improve.

Other shared suggestions among some participants to improve cyber security training were:

- Create a certification program for cyber security professionals;

- Make training mandatory in the workplace;

- Provide funding for training and education programs;

- Work with and hire cyber security specialists

- Start cyber security education at childhood; and

- Have resources and training available online.

Some participants mentioned a need to update the cyber security training currently available.

And, finally, some participants indicated that training is not the problem, and instead cited the lack of public awareness and outreach.

Canada's Way Forward on Cyber Security

The digital revolution has fundamentally changed Canada’s social, economic, and cultural fabric. Canada’s participation in digital life has generated immense prosperity and benefits, and has opened a new gateway to the world. At the same time, it has continued to bring the world to us in new and challenging ways, and introduced threats that could undercut the many benefits of the digital age. Canada’s renewed approach to cyber security must respond to this set of complex, integrated issues.

Canada’s Way Forward

The workbook summarized how Canada will have a renewed cyber security approach guided by the following five principles:

- Protect the safety and security of Canadians online and of Canada’s critical infrastructure;

- Promote and protect rights and freedoms online;

- Recognize and encourage the importance of cyber security for business, economic growth, and prosperity;

- Collaborate and coordinate across jurisdictions and sectors to collectively increase Canada’s cyber security; and

- Adapt to respond to emerging technologies and changing conditions.

Three areas for potential actions were also suggested for review, as follows:

- Resilience: the prevention, mitigation, and response to advanced cyber attacks targeting Canadian systems and institutions, and increasing public engagement on cyber security issues;

- Cooperation and Capability: focus on working together to develop the skills, resources, and tools needed for effective cyber security in Canada; and

- Cyber Innovation: focus on allowing Canadian governments, businesses, and citizens to anticipate trends, adapt to a changing environment, and remain on the leading edge of innovation in cyber security.

Participants were asked to provide their comments on the action areas provided and to identify any other potential actions they feel would improve cyber security in Canada.

It is important to mention that participants generally accepted the proposed action areas. Many participants either indicated that they agreed with them and added their own ideas, or did not mention the examples provided at all. Instead of being distinctly different, this section resulted in many of the same opinions and ideas revealed in the previous sections of the consultation. As such, it acts as a good summary of the full cyber security consultation.

Image Description

This visual displays a list of the ten areas of importance, as identified by the public, for Canada’s Way Forward in cyber security. They are known as “The Big Ten” and include: 1) Privacy; 2) Collaboration; 3) Education; 4) Standardization; 5) Enforcement; 6) Transparency; 7) Strong cyber security measures; 8) Expertise; 9) Investment; 10) Being proactive.

Areas of Focus for Participants

The areas where participants focused their attention were in many cases cross-cutting themes. Indeed, many participants provided broad responses, often with a mix of the ten areas described above.

Privacy

“I am all for my government making sure us Canadians are safe. I will not, however, sacrifice one minute detail of my privacy or freedom in order to gain a little bit of security.”

Privacy was of utmost concern to participants, especially for Engaged Citizens.

It was very clearly indicated by many participants that all action areas should be pursued with the caveat that upholding the privacy rights of Canadians should be at the forefront of Canada’s efforts to improve cyber security.

Some participants mentioned that respecting due process (e.g., requiring reasonable suspicion and warrants by law enforcement in investigation) and keeping personal information collected during investigations private were an important part in upholding privacy rights.

Collaboration

“Promote and cultivate collaboration and partnership opportunities between academia and the private and public sectors within Canada and across the Globe.”

Many participants expressed a need for collaboration; they believed that collaboration, coordination and liaising with strategic partners was important for improving cyber security in Canada. Those partners could include other nations, the private sector, other governmental agencies, and academia.

Other participants expressed a need for collaboration for sharing information and reporting vulnerabilities, issues and weaknesses. Engaged Citizens were less likely than other types of participants to cite collaboration, while Government participants were more likely to.

It should be noted that not every participant thought that the Government of Canada had a responsibility, or should be involved in Canada’s way forward on cyber security, however this sentiment was not widely expressed.

Education

“Education and training are the base.”

For some participants, public education and awareness was vital to Canada’s way forward in cyber security. This could mean more education in terms of the public’s knowledge base or cyber literacy, or for the public to have a better understanding of the significance of cyber security issues. Other Industry participants were less likely to mention public education.

Education was not limited to the public, however. Many participants said that it was important that law enforcement and cyber security personnel have better education and training as well.

Standardization

“Better enforcements of regulations and use of licenses for production and manufacturing.”

Many participants indicated a need to standardize best practices and make guidelines clear and easy to follow. The general idea of “standards” was widely shared.

Some Cyber Security Industry participants expressed the need to standardize techniques used to secure all devices, and thought that Canada should be contributing to these standards internationally.

Enforcement

“There needs to be a national Cybercrime Coordination Centre to triage, deconflict, and coordinate cybercrime investigations across jurisdictions”

Some participants cited the need for law enforcement to enforce fines and prosecute cybercrime. While not mentioned by any Government participants, a few participants indicated that legislation and mandates should be in place to address cybercrime. For others, enforcement was accountability for businesses or manufacturers who do not maintain sufficient security standards (e.g., keepers of personal data should be held accountable when they fail to effectively protect that information).

A few participants indicated that they believed that law enforcement should be focused on major crimes, and not minor infractions. This opinion was expressed almost entirely by Engaged Citizens.

Transparency

“Granting broad discretionary powers without sufficient lawful procedures, due process and transparency compromises the values critical to democracy and Canadian culture.”

Tied to some of the other areas, transparency was a common theme in this consultation. Many participants indicated that there needed to be an overall increase in transparency and public oversight so that stakeholders (e.g., law enforcement, government, and private sector) can be held accountable for the actions they take to ensure cyber security. Some participants were explicit that government should consult with the public as it moves forward to improve cyber security in Canada (cited mostly by Government participants). Some participants stated that transparency and public outreach would ultimately increase awareness of the issues at hand.

Strong cyber security measures

“With respect to cybercrime, a key mitigating factor will be the robustness of encryption methods and security systems used by individuals, corporations, and the general public. This means not having access to ANY backdoors/masters keys/holes into secure systems for even the government, government agencies, or parties tied to the government in any way whatsoever.”

Another common response from participants centered on developing or using strong cyber security measures. Those included the use of VPNs, secured internet, encryption, not using back doors, and keeping software up-to-date. Some participants expressed that these measures should be mandatory.

Expertise

“All organizations whether public, private or government should hire genuine experts who know what they are doing.”

Many participants clearly expressed that any actions in cyber security should be led by skilled personnel who are experts in the field.

Investment

Another common sentiment among participants was investment. This included increased investment in programs, technology, personnel, and education. In regards to government, some participants cited a need for budgetary appropriation; that is, setting aside funds for cyber security measures.

Being proactive

“There appears to be an over-emphasis on resilience, emergency management and disaster recovery, thus presenting a policy of failure as the starting point of a strategy for cyber and critical infrastructure protection. Proactive cyber defence should be added.”

Some participants indicated that actions to improve cyber security in Canada should be proactive in nature, instead of reactive. In fact, it was expressly stated by a few participants that the action areas given to them as examples in the workbook were too defensive, and should instead be more offensive in nature.

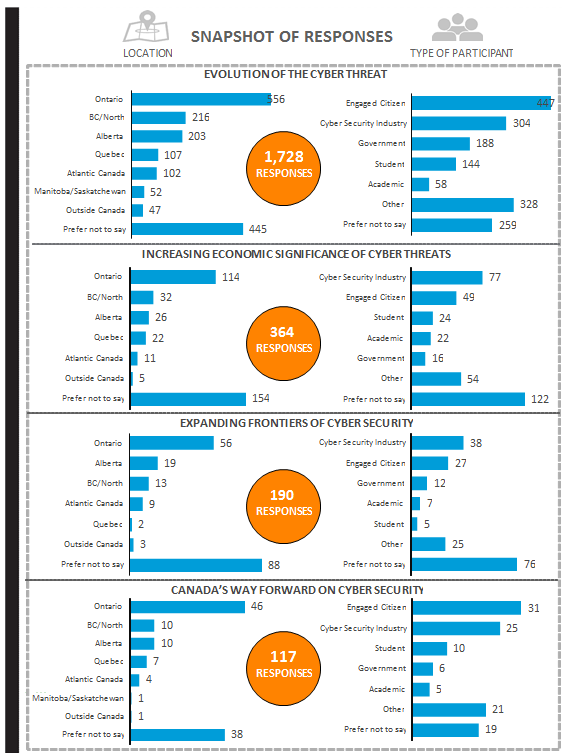

Appendix A – Snapshot of Responses

Image Description

This visual displays 4 sections that represent the 4 main topics of the report. In each section, there are 2 bar charts; one representing the number of responses by region and the other representing the categories of participants who responded.

The first section represents the topic of Evolution of the cyber threat. There were a total of 1,728 responses. In terms of regions, 556 responses were from Ontario; 216 from BC/North; 203 from Alberta; 107 from Quebec; 102 from Atlantic Canada; 52 from Manitoba/Saskatchewan; 47 from outside Canada; 445 preferred not to say. The category of responses included 447 engaged citizens; 304 cyber security industries; 188 Government; 144 Students; 58 academic; 328 other; and 259 preferred not to say.

The second section represents the topic of increasing economic significance of cyber threats. There were a total of 364 responses. In terms of regions, 114 were from Ontario; 32 from BC/North; 26 from Alberta; 22 from Quebec; 11 from Atlantic Canada; 5 from outside Canada; 154 preferred not to say. The category of participants who responded included 77 cyber security industries; 49 engaged citizens; 24 students; 22 academic; 16 Government; 54 other; 122 preferred not to say.

The third section represents the topic of expanding frontiers of cyber security. In terms of regions, 56 responses were from Ontario; 19 from Alberta; 13 from BC/North; 9 from Atlantic Canada; 2 from Quebec; 3 from outside Canada; 88 preferred not to say. The categories of participants who responded included 38 cyber security industries; 27 engaged citizens; 12 Government; 7 academic; 5 students; 25 other; 76 preferred not to say.

The fourth section represents Canada's way forward on cyber security. There were a total of 117 responses. In terms of regions, 46 responses were from Ontario; 10 from BC/North; 10 from Alberta; 7 from Quebec; 4 from Atlantic Canada; 1 from Manitoba/Saskatchewan; 1 from outside Canada; 38 preferred not to say. The categories of participants who responded included 31 engaged citizens; 25 cyber security industries; 10 students; 6 Government; 5 academic; 21 other; 19 preferred not to say.

Appendix B – Stakeholder insights

Key stakeholders from government, critical infrastructure sectors, academia, and the private sector were invited to participate in the consultation. Select responses have been compiled below to provide a sense of the insights received.

Areas for Action

Stakeholders recommended a range of actions that could be taken to improve cyber security in Canada.

Address Cybercrime

- In order to address cybercrime in a manner that respects Canadians’ privacy rights, the following solutions should be considered:

- Target underground forums to disrupt the exchange of powerful and easy to use cybercriminal tools;

- Disrupt the infrastructure of malicious code writers and specialists web hosts through the active identification of developer groups, and a collaboration of law enforcement, government and the ICT industry to dismantle hosting companies;

- Target the proceeds to cybercrime in collaboration with the financial sector; and

- Continue to develop understanding into the behaviour of the contemporary cybercriminal.

- Approaches to tackling cybercrime should include a focus on victim-centred support services that address the unique circumstances of technology-facilitated victimization. Victims may need a range of services, such as guidance on how to restore their financial or personal reputation.

- Increase public awareness of cyber-based victimization, and ensure that criminal justice personnel have adequate training on cyber victimization.

- A templated method to report cybercrime would be helpful. This method could employ a one-window principle which allows all cyber security related incidents to be reported through a single online interface, regardless of their jurisdiction, scale or nature.

- A mechanism needs to be in place, requiring the public and private sectors to upload details of the suspected cybercrime activity (e.g., files, screenshots, emails).

Respect Privacy while Enhancing Security

- Policing in cyberspace should consider the following principles:

- Allow access to digital information upon lawful process only;

- Uphold the right of technology providers to challenge requests on behalf of their customers;

- Require more rigorous forms of legal process for more sensitive information;

- Authorise disclosure in emergencies only;

- Support transparency;

- Individuals and organizations have the right to know when the government accesses their digital information (except in limited cases);

- Modernise rules governing appropriate targets of requests for data; and

- Regulatory or legal reforms in this area must not undermine security, an essential element of users’ trust in technology.

Improve Governance and Partnerships

Within the current cyber security landscape, there are many federal government agencies with similar goals. An opportunity exists to streamline all critical sectors into one single government agency.

- Developing a threat intelligence hub that can cater to the public and private sector is required. Consumers would be able to subscribe to a threat feed via different channels, such as email, SMS messages or web updates, in order to receive timely updates on the latest issues/attacks and receive guidance on how to protect themselves.

- Creating a national centre for Cyber Security Innovation would allow Government, Industry and Academia to jointly develop the necessary education, talent, policies and funding vehicles.

- “If Canada was to align its resources across government, industry, and academia/research…and provide the right forums and incentives for multinational investment, then it is likely that there would be a significant increase in commercial investment in cyber security innovation, solution development, and research in Canada.”

- Create a Government of Canada or Better Business Bureau list of approved e-commerce sites.

Promote Measurement

- Enhance, regularize, and standardize data collection on cyber victimization in Canada. Consider introducing a new national survey specific or a centralized reporting database on cybercrime and cyber victimization.

- Metrics collected and published should match outcomes. The current metrics do not tie into any action or outcome. “Metrics should directly provide guidance on how to improve the current situation in order to meet the desired outcome.”

- “The government needs to tie the ICT benefits (GDP growth) to ICT liabilities (GDP loss) to identify factors such as the size the economy could be, for example, if cyber incidents were minimized.”

Increase Public Education and Awareness

- “…empower girls to study STEM subjects starting in primary school… encourage, retain and create growth opportunities for women in IT and cyber security, including board-level opportunities.”

- Schools should introduce cyber security concepts into curriculum to encourage :

- Safe interactions with strangers on social media and online gaming

- Shaping a digital identity and sharing content online in a smart and safe manner

- Informed choices about buying and selling online

- Provide the following tips to the public to help them protect themselves:

- Research the website before you engage with it

- Throw out emails, posts and texts if you are in doubt of their source

- Protect and value personal information like it is money

- Use safe payment options, like credit cards, when making purchases online

- Turn off Bluetooth and Wi-Fi when you are not using it

- Limit the type of business you conduct over open public Wi-Fi

- Always run the most current versions of software and apps

- Fortify your online accounts by using the strongest authentication tools available, like biometrics, security keys or a one-time code through an app on your mobile device

- Make your password a sentence

- Have a unique password for every unique account

- Public campaigns can address the lack of cybercrime awareness among the general population and can encourage reporting both by victims and others.

- Develop a “cyber newsflash” for new and emerging security threats for Canadians. Short, multi-channel bulletins can be leveraged to communicate cyber news and other security information to Canadians.

- SMEs do not believe their businesses are high-value targets for online criminals. This belief hints at overconfidence in their business’s ability to thwart today’s sophisticated online attacks – or, more likely, that attacks will never happen to their business.

Improve Information Sharing

- Increase government information sharing with the private sector;

- Develop an overarching strategy for information sharing and collaboration to reduce confusion and increase support for information sharing efforts within an organization and among its partners;

- Focus information sharing on actionable threats, vulnerabilities, and mitigation information;

- Establish a meaningful governance process that includes appropriate management of the data shared, from its creation and release, to its use and destruction;

- Remove legislative and regulatory barriers that impede information sharing among private companies, such as the concern that information sharing creates antitrust issues or liability;

- Ensure that government entities who do not require the information shared for cyber security purposes do not have access to it;

- Promote vulnerability handling approaches, which communicate with third party finders, validate and triage vulnerabilities, develop and deploy an update to mitigate the vulnerability, and apply issues updates to systems that are in operation; and

- Understand that privacy is an essential element for building and maintaining global digital trust.

Develop cyber security professionals

- “…there is already a global shortage of approximately 1 million cyber security professionals, and this number continues to grow.”

- Ensure that key cyber security personnel have the ability to attend industry events or government-sponsored events across regions to learn from others and create a network, which can be used to build a stronger program.

Adapt legislative framework