Illustrative Case Studies of First Nations Policing Program Models

Table of contents

By John Kiedrowski, Michael Petrunik and Rick Ruddell

Abstract

The purpose of this research is to provide an in-depth exploration of the two primary policing models supported by the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP): Community Tripartite Agreements (CTAs) and Self-Administered (SA) agreements. Qualitative and quantitative data were collected from a sample of CTA detachments (N = 10) and SA police services (N = 10) across Canada to examine challenges related to funding, the role of CTA and SA officers, and the program's resourcing needs.

Substantial variation in funding across CTA detachments and SA services was found; however, this variation does not seem to be related to some key indicators of police budgets (e.g., geographic isolation). Although a number of challenges were identified by respondents, some of the more common challenges identified included: the amount of time allocated to transporting prisoners, lack of readily available backup when responding to calls for service in remote areas, inadequate infrastructure, difficulties providing 24/7 coverage/service, officer housing shortages, mental health-related calls for service, and difficulties recruiting and retaining FNPP-funded officers. In contrast, respondents indicated they have had a number of successes in the communities they serve related to community programs and engagement initiatives.

Policy considerations are discussed in light of these findings, including improving the funding model for the FNPP; extending funding for infrastructure; reviewing prisoner transportation policies and procedures; advancing inter-departmental coordination at the federal level; creating multi-functional single site facilities serving inter-related justice, healthcare and social services needs; changing the name of the FNPP to Indigenous Policing Strategy (IPS); and assessing the impact of modern treaties on the FNPP.

Author's Note

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Public Safety Canada. Correspondence concerning this report should be addressed to:

Research Division, Public Safety Canada

340 Laurier Avenue West

Ottawa, Ontario, K1A 0P8

Email: PS.CPBResearch-RechercheSPC.SP@ps-sp.gc.ca

Acknowledgements

Compliance Strategy Group (CSG) wishes to express its gratitude to the police executives and other personnel who took part in the survey and those who participated in the follow up interviews. Their time and commitment to this research project are much appreciated. We also thank Savvas Lithopoulos of Public Safety Canada for his contribution to the initial design of the project and his input throughout the study.

Introduction

In June 1991, after extensive consultation with the provinces, territories and First Nations, the Government of Canada announced an on-reserve First Nations Policing PolicyFootnote1 in accordance with the joint recommendation of the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and the Solicitor General of Canada. Based on this policy, the First Nations Policing Program (FNPP) was established under the auspices of the Department of the Solicitor General of Canada to take advantage of its policing expertise (Kiedrowski 2013; Public Safety Canada 2010a; 2013). The transfer of the program was executed by Order-in Council 1992-270 on February 13, 1992, under the Public Service Rearrangement and Transfer of Duties Act, which allows the Government of Canada to transfer the responsibilities and functions of a particular ministry or department to another. The transfer relieved Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada of the responsibility of providing financial support to Indigenous policing. Since the Solicitor General of Canada was responsible for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and policing research, the transfer provided a more suitable departmental environment for the administration of the new FNPP.

A cornerstone of the FNPP is that the Government of Canada enters into financial arrangements with provincial and territorial governments (and in a few instances municipal ones), which have primary jurisdiction over policing, to negotiate and implement tripartite policing agreements involving the Government of Canada, provincial/territorial governments, and First Nation and/or Inuit communities. Such agreements are accomplished through a cost sharing arrangement where FNPP tripartite policing agreements are funded by the Government of Canada (52%) and provincial/territorial governments (48%) and managed by Public Safety Canada (PS). The absence of an obligation on the part of Indigenous communities to contribute to the direct costs of establishing and maintaining their own self-administered (SA) police services provides a strong incentive for their participation (Kiedrowski, Petrunik, MacDonald and Melchers 2013).

Demand for FNPP funded police services supported through the FNPP has grown exponentially. At the end of the 2015-16 fiscal year, 453 First Nation and Inuit communities out of the eligible 686 (or 66 percent of the eligible communities) were covered under the FNPP (Public Safety Canada 2016a). Among these 453 communities, the Government of Canada and provincial/territorial governments fund 186 tripartite policing agreements across Canada (Public Safety Canada, 2016a). These include 38 SAs, 136 RCMP Community Tripartite Agreements (CTAs) and Aboriginal Community Constable Program (ACCP) Agreements, and three Municipal Quadripartite Agreements (MQAs), whereby policing services are provided to Indigenous communities by an adjacent municipal police service, but are funded by the Government of Canada and a provincial or territorial government.

Even though the FNPP is managed at the federal level by Public Safety Canada, the provinces and territories play a vital role in its implementation. There are minor variations in how each province/territory participates in the FNPP. For example, the Atlantic Provinces have opted primarily for the RCMP CTA model, while Ontario and Quebec have opted primarily for the SA model. British Columbia, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba use both models. While the total number of FNPP police officers represent only two percent of all police officers in Canada, their roles are critical in the communities they serve.

Indigenous police services in Canada have a distinct mandate and play a key role in policing Indigenous communities. Of special interest is the challenge of providing 24/7 coverage and ensuring adequate response times for remote and isolated communities (Lithopoulos and Ruddell 2011). To support this priority, PS contracted with Compliance Strategy Group (CSG) to examine the two primary FNPP policing models (SA and CTA) in the five geographic regions (Atlantic, Quebec, Ontario, Prairies, and British Columbia) in which they operate. CSG requested information on 10 CTA detachments and 10 SA police services across Canada in addition to consulting directly with the RCMP, the First Nations Chiefs of Police Association (FNCPA), the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), FNPP Regional Managers and their provincial/territorial counterparts, and federal officials in the operational and policy areas of the program.

Study Objectives

PS views the CTA and SA models as distinct approaches, each of which are better suited to particular communities in terms of factors such as geographical location, differences in capacity, and cultural characteristics. The primary goal of this research is to provide a detailed overview of the CTA and SA policing models and to discuss their respective successes and challenges. In addition, this study examined the way each model meets the current government priorities and FNPP principles. To do so, the following issues were assessed:

- Statistics on crime and conventional police functions;Footnote2

- The level of police services provided to FNPP policed communities, which included measures of:

- Police service determinations of the number of officers/personnel required to meet a community's public safety needs;

- Patrol function, especially differences between day and night patrol;

- The type of services provided to the community in terms of:

- Response/patrol;

- Law enforcement;

- Crime solving and investigations;

- Crime prevention;

- Referrals to relevant partners; and

- Community education.

- Whether data collected by police services adequately measures police performance;

- The extent to which FNPP funded policing include measures of non-traditional policing functions and Indigenous-specific policing functions;

- The sustainability of specific tripartite agreements;

- Whether the FNPP agreement(s) meet(s) the public safety needs of the community;

- Whether the FNPP's current structure adequately addresses the policing needs of Indigenous communities; and

- Whether Indigenous policing costs are consistent with those of police services in non-Indigenous communities similar in size and geographical location.

Finally, this study is part of an on-going process to draw attention to the strengths and limitations of the FNPP one-quarter century after its adoption. It is not intended to be a comparative evaluation but rather an overview of the development and implementation of each FNPP model, funding challenges, the role of CTA and SA officers, and resourcing needs. It is hoped the results will be useful in assisting all police services working with Indigenous peoples in their policy and program planning and implementation.

Overview of the First Nations Policing Program

The FNPP provides funding to support the provision of professional, dedicated, and responsive policing services to First Nation and Inuit communities throughout Canada. The Program is delivered through tripartite policing agreements between the Government of Canada, provincial/territorial governments, and a First Nation or Inuit community or groups of communities. Under the current Terms and Conditions for the FNPP, the relationship between FNPP-funded policing services and provincial/territorial policing services is described as follows (Public Safety Canada 2015):

“For FNPP agreements where the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is the police service provider, the FNPP is meant to enable a level of policing services that supplements the level that has been agreed to pursuant to each Provincial or Territorial Police Service Agreement (PPSA/TPSA) where the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is used or employed for aiding in the administration of justice and in carrying into effect the laws in force in those jurisdictions. FNPP agreements for RCMP services cannot replace policing provided under the PPSAs/TPSAs, and no FNPP funding will be provided for this purpose.

For FNPP agreements where the police service provider is a First Nation or Inuit police service, the FNPP is meant to enable these police services to provide the day-to-day policing services to the First Nation or Inuit community (or communities) specified in the agreement. These police services, however, do not provide specialized services, such as SWAT teams and forensic services. Such specialized services continue to be provided by the provincial or territorial police of jurisdiction on an as needed basis.”

At its inception in 1992, the First Nations Policing Policy was intended to provide “a practical way to improve the level and quality of policing services for First Nations communities through the establishment of policing agreements” (Solicitor General Canada 1992, 1). In 1996, the Policy was updated to cover three broad objectives (Solicitor General Canada 1996):

- Strengthening public security and personal safety to ensure First Nations peoples enjoy their right to personal security and safety through access to responsive police services that meet acceptable standards with respect to quality and level of service;

- Increasing responsibility and accountability by supporting First Nations in acquiring tools to become self-sufficient and self-governing through the establishment of structures for management, administration, and accountability to the public in First Nations police services; and

- Building new partnerships to implement and administer the FNPP in a manner promoting trust, mutual respect, and participation in decision-making.

In 2014, when the Terms and Conditions for the FNPP were updated, emphasis was placed on supporting policing services that are professional, dedicated, and responsive to the First Nation and Inuit communities they serve. The Performance Measurement and Evaluation Strategy of the FNPP defines these three terms as follows (Public Safety Canada 2014):

- Professional Policing

First Nation and Inuit communities have access to “professional policing” meaning that police officers working in these communities must meet a level of professionalism equivalent to that of other police officers in that province or territory for the purpose of carrying out their duties. This includes (but is not limited to) mechanisms, standards, policies or procedures developed by the police service, police board, police commission, advisory body or any provincial or territorial government organization related to recruitment, training, appointment and authorities, discipline and dismissal, and operational practices.

- Dedicated to Communities

The FNPP, which sets out a framework for the negotiation of tripartite policing agreements between the federal government, provincial and territorial governments, and First Nation and Inuit communities, must specify a level of service delivery in which there is an appropriate presence of First Nations and Inuit people in their own communities. This is a recognition that public safety issues can be effectively addressed when First Nations or Inuit individuals are employed by a police service to provide a dedicated public safety presence within their own community, pursuant to a provincial appointment.

- Responsive to Communities

First Nation and Inuit communities have access to policing that is responsive to their public safety needs. Community members have an appropriate role in working with their police services through police boards, commissions, or advisory bodies that are representative of their communities. These bodies work to further police accountability and strong governance and help establish policing priorities. Communities have input in determining the type of policing they receive through the FNPP. The selection of a police service model should, however, balance the need for cost-effectiveness and the particular characteristics and capacities of a community.

Police services in communities where FNPP agreements are in place must be responsive to the cultural and linguistic characteristics of the peoples they serve and police officers and other personnel must have specific knowledge of a community's socio-demographic and cultural profile.

Two main types of agreements have been implemented under the FNPP:

- Self-Administered (SA) Agreements – Agreements between the Government of Canada, a provincial or territorial government, and one or more Indigenous communities. Under these agreements, the First Nation or Inuit community (or group of communities) is responsible for administrating its own police service pursuant to provincial/territorial policing legislation; and

- Community Tripartite Agreements (CTAs) – Agreements that are entered into after the conclusion of a bilateral Framework Agreement involving the Government of Canada and a provincial or territorial government. Once a bilateral Framework Agreement is concluded, the Government of Canada and the respective provincial or territorial government can enter into individual tripartite policing agreements (i.e., CTAs) with each Indigenous community (or group of communities) mentioned in the bilateral Framework Agreement. Under a CTA arrangement, the First Nation or Inuit community (or group of communities) receives policing services from a dedicated contingent of police officers from the RCMP.

Although SA agreements and CTAs represent the majority of agreements concluded under the FNPP to date, additional types of agreements exist. For example, there are also some Municipal Quadripartite Agreements (MQAs), which are agreements between the Government of Canada, a province or territory, a First Nation or Inuit community (or group of communities), and a municipal police service provider. Similar to a CTA, the First Nation or Inuit community (or group of communities) receives policing services from a dedicated contingent of municipal police officers. An overview of the agreements in place at the end of the 2015-16 fiscal year is provided in Table 1.

| Overview | SA Agreements | CTAs and ACCP Agreements* | Municipal Quadripartite Agreements |

|---|---|---|---|

Number of Agreements |

38 |

136 |

3 |

Number of Communities Served |

170 |

280 |

3 |

Population of Communities Served |

168,968 |

250,870 |

1,989 |

Federal Expenditures |

$78.5 million |

$41.9 million |

$0.679 million |

Provincial Expenditures |

$72.4 million |

$38.7 million |

$0.627 million |

Total Expenditures |

$150.9 million |

$80.6 million |

$1.3 million |

| Source: Public Safety Canada (2016a). | |||

| *A small portion of the agreements in this column includes the remaining Aboriginal Community Constable Program (ACCP) agreements. The ACCP is a legacy program established in the 1970s, where the federal and provincial/territorial governments entered into bilateral agreements to provide RCMP services in First Nation and Inuit communities. Since the First Nation or Inuit community (or group of communities) is not a signatory to ACCP agreements, the intent has been to transition the ACCP to tripartite FNPP agreements. | |||

FNPP agreements are usually re-negotiated every five years. To manage the FNPP, PS negotiates and funds the policing service agreements with the provinces and Indigenous communities. Department officials work with provincial, territorial and sometimes their municipal counterparts to ensure consistency in the application of the agreements and to monitor compliance by the parties with the terms and conditions of the agreements. Contribution agreements (e.g., self-administered agreements) also provide guidelines on how funds can be spent as well as specifying which expenditures are ineligible (e.g., overtime budgets in excess of 10 percent of the budget for officer salaries, depreciation on vehicles and equipment, interest on loans, performance bonuses and hospitality expenses; Public Safety Canada 2015).

While there has been much written about these types of agreements (e.g., Public Safety Canada 2010a, 2010b), the focus of this research will only be on the two primary funding models: SA agreements and RCMP CTAs.Footnote3

Previous Research on CTA and SA Policing Models

Since the FNPP's inception, few studies have examined the CTA and SA models of policing. One of the earliest studies examining RCMP and Indigenous policing was a comprehensive national survey of officers policing Indigenous communities conducted by Murphy and Clairmont (1996). A key finding was that the ratio of police officers to the size of the population served was lower in SA than CTA communities. The authors further found that all of the RCMP officers in CTA communities had received regular recruit training compared to 80 percent of officers serving SA communities. Furthermore, RCMP officers working under a CTA were more likely than officers working within SA agencies to receive specialized training. Finally, the authors identified differences in how communities are policed, with police serving SA communities more inclined to follow a community policing based model and the RCMP more likely to follow a conventional law enforcement model.

The Prairie Research Associates' (PRA) (2006) evaluation of the FNPP compared SA and CTA policing services in terms of several factors. One issue examined was the sustainability of the policing agreements. PRA found that six SA services disbanded and two CTAs had been discontinued since the inception of the FNPP in 1992. The reasons identified for the discontinuation of some SA agreements were limited community capacity to administer a police service, too rapid expansion of police services, and difficulties with officer recruitment and retention (PRA 2006). Many of these agencies were under-resourced and, in some cases, the communities and police leaders may have lacked the administrative or leadership capacity needed to succeed (Canadian Press 2013). In contrast, PRA further pointed out that CTAs were able to rely upon the resources of the larger police services, such as the RCMP, to provide greater administrative support than that available under independently operating SA agencies. In terms of police activity indicators (e.g., calls for service, crime rates), there were no clear differences between CTA and SA police services.

Alderson-Gill & Associates (2008) conducted a similar study focusing on how police services are delivered in Indigenous communities. In terms of the reasons given for becoming a police officer, the authors found that respondents working in SA communities were more likely to cite community-oriented concerns such as a desire to “help my people” as a motivation. This was in contrast to officers working for the RCMP in CTA communities who were more likely to say they joined the police service because of security, income, or opportunities for training and travel. Officers in SA services were less likely to have clear career advancement prospects, receive specialized training, or have mentoring opportunities when compared to RCMP officers working under CTAs.

These studies revealed that there were also differences with regard to how communities are policed. In SA communities, the police officers spend more time answering calls for service, gathering local information about crime, or patrolling than do officers policing CTA communities. Similar to the findings of Murphy and Clairmont (1996), Alderson-Gill & Associates (2008) found that the policing styles in SA communities are more focused on “social development” or “community development”, whereas the RCMP respondents were more likely to emphasize law enforcement as a key goal. Finally, the authors found a higher attrition rate among police officers serving SA communities than those working in RCMP CTA communities.

Public Safety Canada's (2010a) evaluation of the FNPP focused on the responsiveness of policing services in the two types of communities. They found that police working under SA agreements were more likely to say that that their policing style emphasized “culturally appropriate policing” whereas police working under CTAs were more likely to say that their emphasis was on “more effective policing” (Public Safety Canada 2010a,13).

Public Safety Canada (2010a) also asked community representatives to provide an assessment of their police effectiveness based on selected aspects of service. As shown in Table 2, those services working under SA agreements were perceived to do a better job keeping citizens safe, protecting property, being visible, and providing a prompt response to calls for service. In contrast, the CTA police services were perceived to have higher levels of professionalism, to be more effective at Criminal Code and provincial statute enforcement, to be more independent from political influences that had the potential to be inappropriate, and to be more effective working with other police services. There were no perceived differences between the two types of organizations in terms of crime prevention or enforcing band bylaws.

| Attributes | CTAs (%) | SAs (%) |

|---|---|---|

High level of professionalism |

93 |

75 |

Enforcing Criminal Code |

87 |

75 |

Working with other police services |

86 |

67 |

Enforcing provincial statutes |

72 |

58 |

Independent from inappropriate political influences |

72 |

50 |

Keeping citizens safe |

64 |

67 |

Protecting property |

50 |

67 |

Providing crime prevention information |

44 |

50 |

Being visible |

39 |

50 |

Preventing crime |

33 |

33 |

Enforcing band bylaws |

31 |

33 |

Prompt response to calls for service |

28 |

33 |

| Source: Public Safety Canada (2010a, 14). | ||

Public Safety Canada (2010c) re-analyzed data collected by Ekos Research Associates (2005) which included responses from a sample of 2,002 on-reserve residents of First Nations communities concerning a variety of issues surrounding police performance in SA and CTA communities. On questions regarding keeping citizens safe, responding quickly to calls for service, and supplying information to the public on ways to keep crime down, respondents in SA communities rated their police services slightly higher than did respondents in the CTA communities. Moreover, when asked how they would rate the performance of their local police service in responding quickly to calls for service, those in the SA communities (36%) provided more “satisfied” or “very satisfied” responses than did those surveyed in CTA communities (30%). Respondents from SA communities (41%) also rated their police services higher than did those residing in CTA communities (37%) in terms of how satisfactory they considered the relationship between the police and public.

Finally, Ruddell and Lithopoulos (2011) analyzed data obtained from a national-level survey of police officers working in isolated Indigenous communities. Respondents were asked to assess the quality and effectiveness of services that their police services provided. These questions involved 10 core policing tasks, including enforcement of laws, keeping the community safe, response times, police visibility, delivering community presentations, providing victim services, and working with local leadership and youth and schools. The authors found that the RCMP officers provided a more positive evaluation of their agency's performance on every dimension of service delivery compared with that provided by officers working for SA police services (Ruddell and Lithopoulos 2011, 164).

Methodology

Unlike some of the previous studies reviewed above, the current research does not intend to directly compare the SA and CTA policing models. Instead, the aim of presenting these two case studies on the SA and CTA policing models is to provide an in-depth illustration of how policing services are delivered to FNPP-served communities across the five national regions and how different operational factors influence those organizations.

To conduct the case studies, both qualitative and quantitative analyses data were collected. Qualitative data were collected using a questionnaire sent to 10 CTA police detachments and to 10 SA police services selected using a purposive sample. The selection criteria used were geographic location (e.g., representation from each national region), accessibility of data and other information, and the availability of agency staff to complete the questionnaire. To ensure anonymity, the names of the police services were not identified. On completion of the questionnaire, follow up interviews were carried out with some police executivesFootnote4 and representatives from the federal and provincial governments to seek further clarification on their comments. Of the 20 police services invited to participate, eight respondents were from SA police services (an 80% response rate) and 10 were from RCMP CTA detachments (a 100% response rate).

Quantitative data were collected from each participating police service and Statistics CanadaFootnote5 for a five-year period (2009 to 2014) to show trends over time. Where five-year data were not available for the police services identified, absence of such data was noted. Data on funding included the most recent fiscal year (2014-2015).

To help ensure the anonymity of the respondents, the regions in which particular police services were located and the size of the service were not identified. Each police service was provided a code: SA (1 – 10) for a self-administered policing service and CTA (1 – 10) for an RCMP CTA detachment. Finally, data were not available for all police services reviewed.

Self-Administered Agreements

Background

The SA agreements are negotiated by the First Nation or Inuit community (or group of communities), provincial or territorial governments, and the Government of Canada.Footnote6 Under such agreements, the communities are responsible for establishing and administrating their own police service, often through the creation of an independent police governance board. An exception to this is in Quebec, where most of the powers of the police governance board (e.g., hiring, discipline, etc.) are exercised by the Director of the police service or the oversight bodies set by the provincial policing legislation.

Each SA agreement is negotiated independently. Such services are typically developed over several years often with the assistance of the RCMP, the Sûreté du Québec (SQ), or the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP). The police officers, First Nation constables, or other individuals who are part of these police services, are appointed pursuant to provincial/territorial policing legislation. In Ontario, for example, police governance boards authorize the employment of constables who are appointed by the Commissioner of the OPP under section 54(1) of the Police Services Act.Footnote7 In contrast, in Quebec, the Band Council hires the Director of police, police officers, and support staff, in accordance with the standards specified in section 115 of the provincial Police Act.

Federal and provincial governments fund SA police services under the FNPP through agreements signed by the Chief and Council of a First Nations community. The terms and conditions of the FNPP state that SA services are meant to provide day-to-day policing to the communities they serve. Specialized services such as Emergency Response Teams (ERT) and forensic services are provided by the provincial or territorial police of jurisdiction on an as needed basis (Public Safety Canada 2015).

Each SA police service is headed by a Chief of Police reporting to the police governance board, which is often referred to as the Police Commission or Police Board. In Quebec, however, the SA police service is under the direction and command of the Director of the police service, who reports to the Council. The Director has the role and responsibilities described in the agreement between the Government of Quebec and the Band Council (this agreement is pursuant to section 90 of the provincial Police Act). Under SA agreements, Police Boards (or in Quebec, the Directors) are responsible for hiring police officers and ensuring they have the necessary training. They are further responsible for public oversight including the establishment of performance standards and grievance procedures in matters of discipline and dismissal.

Table 3 provides a list of the number of SA agreements in place at the end of the 2015-16 fiscal year, including the number of Indigenous communities served, the size of the populations served, and the number of full time police officer positions by province (and overall). In Ontario and Quebec, Indigenous leaders strongly favour the SA approach while elsewhere there is a preference for the CTA model. In the Atlantic region, there are no SA police services. In Quebec, 71 percent of the First Nations on-reserve population is covered by an SA agreement (Public Safety Canada 2016a). In Ontario, 75 percent of the First Nations on-reserve population is covered by an SA agreement or by the OPP-administered Ontario First Nations Policing Agreement (OFNPA; Public Safety Canada 2016a). In some cases, the police services may have additional police officers funded by other sources.

| Province/Territory | Number of Agreements | Number of Communities | Size of Population Served | Number of Police Officers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

BC |

1 |

10 |

3,401 |

10 |

AB |

3 |

7 |

12,367 |

50 |

SK |

1 |

5 |

2,412 |

9 (+5 special officers) |

MB |

1 |

6 |

9,689 |

36 |

ON |

11 |

103 |

86,629 |

427 |

QC |

21 |

39 |

54,470 |

305 |

NB |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NS |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

PE |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NL |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

YT |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NT |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NU |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Totals |

38 |

170 |

168,968 |

837 (+5 special officers) |

| Source: Public Safety Canada (2016a). | ||||

The implementation of the SA model among the regions appears to be influenced by differences in provincial/territorial policies, resources, and legislative frameworks. No new SA police services have been added for over a decade, despite the fact that “since 2006, 16 First Nations communities that had passed official Band Council Resolutions to join the First Nations Policing Program had been formally notified that they were not able to join or were still waiting for a reply to their applications. According to Department officials, program funding does not provide resources to expand the Program” (Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) 2014, 11). While the SA model may be adopted, policing services are not delivered in the same way in every community or region. This can likely be attributed to a variety of factors, including differences in provincial/territorial policing legislative frameworks as well as the notion that FNPP-funded police services should be responsive to the cultural needs of the particular Indigenous community (or group of communities) they serve.Footnote8

For some communities, the SA policing model poses significant administrative and structural challenges. Since the inception of the FNPP in 1992, 20 SA police services have been disbanded. Lithopoulos (2016) noted that few of the disbanded agencies were operational for more than a decade, that the average disbanded department employed no more than five officers, that the average size of communities served was about 1,700 residents, and that the average budget was $0.7 million. In contrast, on average, the SA policing services that have survived serve approximately 4,500 residents with a detachment size of about 22 officers and a budget of about $4.0 million. These findings are similar to those of recent U.S. studies indicating that small non-Indigenous law enforcement organizations are often prone to being disbanded during their first decade of operation (King 2014). This issue is exacerbated in Indigenous communities, where police services face unique challenges that arguably impact their sustainability (e.g., retention of officers, remoteness, etc.).

In a report on the cancellation by federal and provincial governments of funding for SA policing services, Barnsley (2002) noted that these actions were associated with financial mismanagement by the police service, inadequate segregation of duties, less than ideal utilization of contributed funds, automotive insurance, payment to vendors, lack of general insurance, compensation of employees, maintenance of personnel files, safeguarding of assets, payment of honoraria, travel expenses, retention of financial records, budgets and use of surplus funds (see Consulting and Audit Canada 1999). According to Lithopoulos (2016, 17), the 20 disbanded SA policing services suffered from both “a liability of newness” and their “diminutive size.”

Police Reported Crime Statistics in Selected SA Communities

Data collected by the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics and from the annual reports of selected police services were used to provide insight into crime trends.Footnote9 Included in these indicators are the Crime Severity Index (CSI), which measures the severity of police-reported crime by accounting for both the amount of crime reported by police in a given jurisdiction and the relative seriousness of these crimes (Statistics Canada 2009). The CSI is considered a “volume index” in that it principally intends to measure changes in volume of crime over time by weighting each offence using a measure of relative severity and then dividing by population size.Footnote10 Figure 1, which looks at six SA services over a 4-year period (2010-2013), shows that with the exception of two services (SA4 and SA6), crime decreased from 2010 to 2013. The community policed by SA1 witnessed the greatest (65.3%) decline in the CSI, from 336.38 to 127.29 whereas SA5 saw a 26 percent decline in the CSI, from 864.14 to 639.46. Communities policed by SA6 had the largest percentage increase (31.2 %) in CSI rising from 242.26 to 317.92. While CSI has declined in some on-reserve communities similar to the decline observed in off-reserve communities, the CSI in First Nations overall is substantially higher than the national CSI.Footnote11

Figure 1: Crime Severity Index across SA Police Services

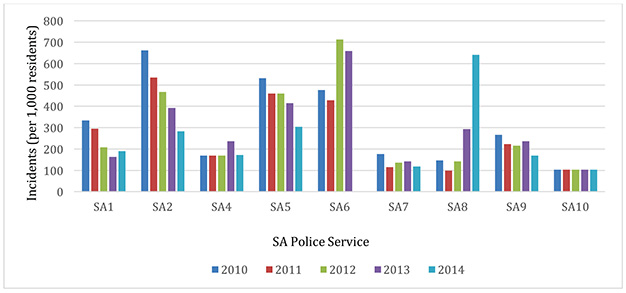

Figure 2 shows the number of criminal incidents per 1,000 community residents. Between 2010 and 2014, the number of criminal incidents per 1,000 inhabitants decreased for the communities served by the following agencies: SA1, SA2, SA5 and SA7 and SA9. SA2 had the steepest decline (57%) from 662 incidents per 1,000 residents in 2010 to 283 in 2014. However, the number of incidents in the community policed by SA8 almost doubled, from 147 in 2010 to 293 in 2014. The community policed by SA6 had an increase of 38 percent in the number of incidents per 1,000 inhabitants from 476 in 2010 to 659 in 2013.Footnote12 In communities policed by SA4 and SA10 the number of incidents per 1,000 residents remained relatively stable from 2010 to 2014.

Figure 2: The Number of Criminal Incidents per 1,000 Inhabitants across SA Police Services

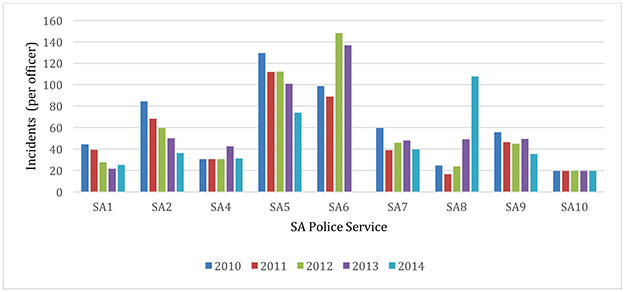

With crime rates generally declining in many communities, data on police service workloads and deployment are important to consider. This is because these factors are affected by the number and type of actual incidents reported to the police, many of which involve various kinds of assistance services as opposed to crime per se. The number and type of incidents is a measure of the demand on police services to handle calls for service from the initial call to report an offence or occurrence to its resolution.Figure 3 shows the number of criminal incidents per police officer.

As shown in Figure 3, five (SA1, SA2, SA5, SA7, and SA9) of nine SA police services experienced a decline in workload demand in terms of incidents per officer. From 2010 to 2014, the actual incidents per police officer in SA2 decreased from 84.6 to 36.1, representing a 57 percent decline. In the case of SA4 and SA10, demand for police services over the four-year period remained relatively constant. One limitation of these data, however, is that the type and relative seriousness of incidents recorded are unknown. Although the annual number may remain stable or even decrease, officer workload might actually increase when there are a larger number of more serious occurrences because of the greater amount of investigative time required.

Figure 3 also reveals that the communities policed by SA6 and SA8 witnessed a substantial increase in the police workload per officer. From 2010 to 2014 the demand on policing services for SA8 increased by 334.7 percent from 24.8 to 107.8 actual incidents per officer. From 2010 to 2013, policing services for SA6 increased by 38.4 percent, rising from 98.8 to 137 actual incidents per officer.

While Figure 3 generally reflects a workload decline for the SA policing services in terms of numbers of criminal code incidents, this may not necessarily reflect overall workload but rather changes in deployment as in the case of police officers spending more time on mental health or substance abuse crisis incidents, community policing, or public order maintenance activities that are not readily measured (see Sparrow 2015).Footnote13

Figure 3: The Number of Criminal Incidents per Officer across SA Police Services

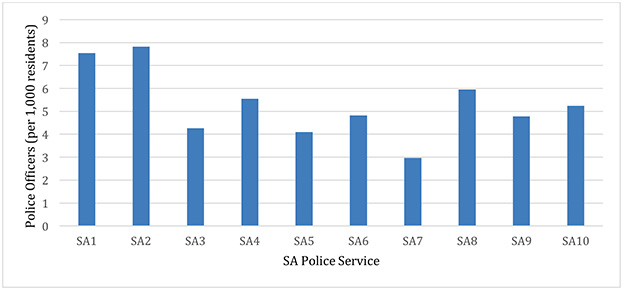

The national rate of police officers per 1,000 off-reserve residents is 1.92 officers (Mazowita and Greenland 2016). Based on the information provided in Table 3, the number of authorized police officersFootnote14 per 1,000 residents is 4.95 officers for SA services. Figure 4 provides an overview of the number of authorized police officers per 1,000 residents for the specific SA services sampled in this study. As shown, the number of police officers per 1,000 residents ranges from 2.96 (SA7) to 7.82 (SA2), with an average rate of 5.30 officers per 1,000 residents. An argument put forward by some police executives and those involved with managing the FNPP is that there is a need for more police officers to address higher crime rates on reserve than off reserve (Kiedrowski 2013). Moreover, the large geographical spaces that must be policed in rural and remote areas also require a greater number of officers than do urban locations (Ruddell 2016). However, the number of police officers per capita in Indigenous communities may not necessarily be driven solely by crime rates and policing needs. Budgetary constraints and the large expenditures allocated for salaries and benefits may also be impacting SA police service size.

Figure 4: Number of Police Officers per 1,000 Residents across SA Police Services

From the information provided in Figure 4, we can extrapolate that the number of police officers per capita also has bearing on police operations. Agencies with fewer than five officers, for example, may not necessarily be able to provide 24-hour policing services seven days per week, especially if timely back-up is required.Footnote15 Further information is required on the number of officers assigned to patrol, workload levels, travel time, and the time expended handling calls for service.

Funding SA Agencies

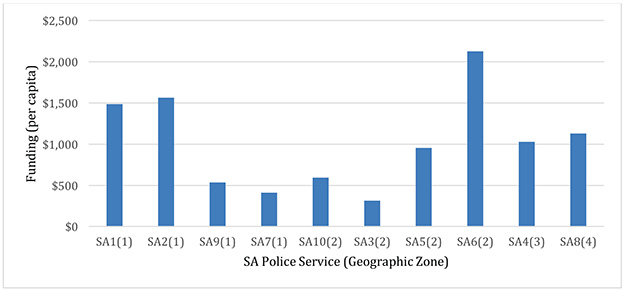

Figure 5 shows SA police funding per capita, taking into account the geographic zones that reflect each SA police services' relative degree of geographical isolation. The classification of these geographic zones is based on distance from urban areas and accessibility (i.e., the extent to which communities have year round road access).Footnote16

As shown, substantial variation in police funding per capita exists across the provinces. Geographic isolation does not appear to be a factor in allocating funds to these agencies. The three agencies with the most funding per capita (SA1, SA2, and SA6) are all located in communities close to urban areas. By contrast, the agencies in the two most remote communities receive much less funding per capita (e.g., SA4 receives $1,000 per capita whereas SA6 receives twice as much). Saying “the only thing consistent about the FNPP is the inconsistency in funding policing services”, a police executive from one of the SA policing services pointed to the apparent inconsistencies in the methodology used under the FNPP to determine how funds are allocated.

Finally, although the terms and conditions of the FNPP allow for the carry-over of unexpended funding, when an SA police service overspends its budget, the Chief and Council may need to provide funds to offset any shortfalls. In other instances, a police service may need to make cuts in its delivery of services. For example, in one case where an SA police service had used up 100 percent of its FNPP budget before the end of the fiscal year, it had to cover the cost overrun out of its own budget as the FNPP negotiated budget did not cover certain required policing services.Footnote17

Figure 5: Per Capita Funding in SA Police Services by Geographic Zones

SA Police Leaders Comments

Eight out of 10 SA police services contacted completed a survey with a series of questions focusing on the following areas:

- Location of police station or detachment;

- Police operations;

- Level of policing services; and

- Measuring effectiveness in their police service.

Location of Police Station or Detachment

The SA police service providers were asked to identify any special considerations given to geographical factors that might influence demands for policing services. An example of this is the responsibility of police services for moving prisoners who are making court appearances or going to hospitals for planned or emergency medical care.

A key element identified by six of the respondents was the time spent transporting prisoners to different locations. Often, prisoners are moved from police stations with limited holding cell capacity to a detention centre; in some cases, a police service (e.g., SA9) may lack cell blocks to separately house male and female prisoners, or juveniles and adults. Respondents from SA2 and SA6 indicated they drive great distances to transport prisoners, attend court, or meet with Crown Attorneys. In another instance, a police service (SA5) indicated that it had been unsuccessful in hiring special constables to supervise cell blocks and had to use regular police officers for this purpose. Since this service had cell spaces for only two prisoners, any additional prisoners had to be moved to a detention centre or to another police detachment, provided space was available. This required a four-hour round trip by two officers.

Several SA police services (SA2, SA3) have made arrangements with other police services (e.g., OPP, SQ or RCMP) to transport prisoners. Only SA2 indicated that it had secured funds to hire a special constable to transport prisoners; the others had to deploy full time regular police personnel (two persons per vehicle) to transport prisoners.

Another factor influencing demand for police services is travelling distance between communities. The respondent from SA2 noted that travel by road is 151 km between two communities. SA6 noted their patrol officers drive over 160 km from one of end of their patrol area to the other. SA4 pointed out that the lack of year-round access to many of the communities within their patrol area poses major challenges for service delivery. The respondent from SA4 noted that due to the remoteness of its communities, it can take up to four hours in ideal weather conditions and longer in poor conditions to receive police patrol back up.

Some communities are located in close proximity to towns and are accessible by road year round. Others are only accessible by air or during a short period of time in the winter when temporary roads permit motor vehicle access. One of the police chiefs stated that there is only a six week-period in which winter roads can be used to ship replacement police vehicles, machinery, and parts.

The respondent from SA3 noted that approximately 80 percent of their communities are only accessible by aircraft. SA4 and SA8 serve remote communities accessed only by aircraft. There are several challenges associated with policing such communities. Few SA police services have access to an aircraft; the only alternative to access urban areas are scheduled or charter commercial flights which are costly (approximately $1,200 per round trip).

In many remote communities, police stations either do not have a garage or lack access to one. If a garage is needed to repair or store a vehicle, the police are compelled to rent a provincial transportation facility at $65 an hour. One police chief noted that an oil change in the north can cost approximately $500 compared to an oil change in an urban community costing around $50. If police station personnel want to do construction or repairs, supplies must be shipped via the winter road or by air at a cost of $1 per pound.Footnote18

A respondent from the fly-in community (SA4) identified the challenges of providing housing for their staff. There is a lack of rental accommodations and in many Indigenous communities, there is also a housing shortage. Some police officers must live with extended family or in “teacherages”,Footnote19 hotels, or construction camps. Many of these living arrangements, however, are only available on a short term basis and officers may be asked to relocate due to other operational priorities. If officers reside with extended families, there is often a lack of privacy and rest is limited as bedrooms may need to be shared with others and household members may sleep in shifts.

In contrast, isolation pay and housing for police personnel were generally not issues for the SA5 service. A respondent from SA8, however, raised the concern that their colleagues working for the provincial police who received monies for housing and the cost of living were better served. The respondent further noted that in other sectors such as health and education, the federal government provides monies to Indigenous communities to build homes specifically for nurses and teachers. One respondent pointed out that their agency does provide remote pay depending on the location of their community. A police executive from SA4 noted that this pay is much lower than that paid to neighbouring police services. Because of their location, remote pay is essential to ensure officer retention. A police executive from SA4 further noted that, among the police officers living in the remote communities, only seven percent have access to housing and live in the communities they police. As part of their budget, the police services must provide additional fees to pay for rental of rooms and housing which are not funded by the FNPP.

Respondents from the SA services were also asked to provide comments regarding the impact that community attributes may have on their workload. Communities based primarily on resource extraction and processing pose two major challenges for police services. First, high labour needs have led to rapid population increases in some of these rural and remote communities resulting in a large transient mostly male population with little attachment to the community. Consequently, additional police personnel are required to respond to an increase in accidents and crime most typically assaults, traffic offences, and other crimes related to excessive use of alcohol and drugs (Ruddell and Ortiz 2015). Second, resource development on Indigenous lands has resulted in protests (SA6 and SA3) that place unexpected pressure on police services.

Another problem related to resource development in Indigenous communities is the recruitment of police officers. The respondent from SA8 noted that some officers will leave policing to work for mining companies that offer higher wages and benefits. Problems in recruiting candidates from within the community to work in policing roles may result in a need to recruit non-Indigenous officers.

The respondent from SA1 also raised an interesting consideration that is affecting policing resources. This police service spends substantial time and expense in applications for special kinds of criminal justice measures such as orders of recognizance or peace bonds including Section 810 ordersFootnote20 and applications for dangerous/long-term offender status. The respondent notes that such time and resource consuming tasks are not funded adequately by the FNPP and no compensation is received from the province. Nonetheless, they are expected to complete forms and submit the required information.

Participants were further asked to provide comments regarding how their agencies can be vulnerable to unpredictable increases in policing costs due to the challenges of an aging population or inadequate infrastructure in their communities. Respondents from SA8 and SA2 noted that due to the vast distances they have to patrol, there is a substantial increase in capital costs due to maintenance and replacement of vehicles. This is especially true in the case of fly-in communities where additional costs are associated with transportation and the costs of police equipment (e.g., shipping vehicles, fuel, and parts).

Additionally, the respondent from SA8 noted that due to location, they either cannot receive or receive limited information technology support. Similar concerns were raised by an officer from SA9 who noted that the FNPP funding agreement does not allow for the costs of equipment to help with police administration and police work itself (e.g., computers in cars). SA4 further stated that a detachment commander may either not be available or not have the experience to overcome some of the challenges of policing these communities. Consequently, in some of the communities, headquarters may need to provide supervisory site and managerial support – both via phone and visits.

The respondent from SA5 pointed out that providing police services to Indigenous communities under financial co-management results in police stations or cell blocks falling into disrepair. In some cases, the police services will provide the materials needed for repairs while the communities provide the labour. In other cases, the police service uses some of its operating budget to pay for emergency repairs (e.g., replace a broken furnace). An officer from SA4 pointed out that their police service is vulnerable because of inadequate infrastructure and detachment buildings in poor condition. Communities cannot afford to make the capital expenditures required for new buildings or renovating existing ones. In many cases, the detachments are converted houses or trailers placed on gravel or concrete pads. The pads are subject to heaving and cracking and the trailers subject to leaks and mould. On average, to re-level a pad and repair a trailer can cost up to $30,000. One police Chief noted that “in five cases we needed to replace the low-pitch roof at a cost of $25,000 per unit. In other locations, furnaces fail and fuel tanks need to be replaced. All these costs are difficult to budget for and, once a problem is identified, repairs cannot be delayed.” The Chief explained:

“This puts significant pressure on the operations budget. The savings need to be found within the budget to cover the cost of repairing aging buildings. With funding increases of only 1% annually, there are insufficient funds for these large infrastructure repair costs. They are funded by cutting back on other areas of the policing budget such as training for staff. Fewer police cruisers are purchased and older vehicles run longer. We have had no increases to building operations and maintenance service since 2009. Costs run to an extra $400,000 annually that we are not funded for.”

Police Personnel and Operations

All of the SA police services that participated in this research have recruited both Indigenous and non-Indigenous staff. Only SA5 and SA6 have recruited a greater proportion of Indigenous policing personnel than non-Indigenous police. These results show that the proportion of Indigenous officers seems to be declining when one contrasts this finding with research carried out by Murphy and Clairmont (1996) or Alderson-Gill & Associates (2008).

Respondents were asked to provide insight regarding the availability of police services. Among the police services that responded to the question of whether 24/7 services are provided, SA3, SA8, SA5, and SA9 all indicated they provide this type of coverage. For those providing 24/7 policing service, some pay their police officers for overtime beyond their regular shifts. The other three police services (SA4, SA1 and SA6) have their officers on call and pay them according to the number of hours worked. There is some variance in terms of shift schedules. One police service has their patrol officers working an eight-hour shift, five police services allow for a 10-hour shift, and three police services authorize 12 hour shifts.Level of Policing Services

All the SA police services reported that their officers are involved in a variety of informal community activities including hockey games and fishing derbies as well as more formal endeavors such as delivering crime prevention programs and participating in talk shows on the local First Nation radio station. The rationale for public involvement is the belief that these activities build rapport with community members. This perspective acknowledges that the police, acting alone, can neither create nor maintain safe communities.

The police can help in their crime control activities by setting in motion voluntary local efforts to prevent disorder and crime. In this role, they are adjuncts to community crime prevention efforts such as target hardening, neighbourhood watch, and youth and economic development programs. Respondents from the SA policing services have noted that these activities usually involve partnership with others in the communities. For example, SA2 has a community safety officer who works with local service organizations. SA3 collaborates with community safety groups, and SA6 works with their police commission to promote community safety. Officers in SA5 have developed local policing committees that involve elders and other community members helping to identify community safety issues (e.g., traffic concerns such as speeding).

Measuring Effectiveness

Respondents from the SA police services noted that under the FNPP, they are required to submit information regarding their activities to the Chief and Council or the police governance boards. For example, SA1 collects additional information by regularly conducting community police satisfaction surveys.

Most of the police services submit reports to either the Council or Police Commission regarding crime statistics and other policing activities. However, in one case, a police service (SA3) provides no report with regard to the role the police play within the communities they serve. The Chief and Council have not formally acknowledged this particular policing operation. However, the police do have an informal process and, upon request by the Council, do hold meetings with them. While all the police services have administrative procedures in place for collecting performance related data, they have different degrees of administrative expertise, computer software, and record management systems. These challenges are exacerbated by a lack of clarity and consistency in standards for measuring police performance.Footnote21

Respondents from the SA police services also pointed out that, where requested, they are involved in non-traditional policing functions. For example, SA1 participates with the Elder's Council when it conducts cultural teaching and healing circles. Another agency (SA5) makes involvement in community events part of its policing plans for members and support staff.

The enforcement of Band Council by-laws is a contentious issue and none of the SA police services sampled in the current study enforce them, citing factors such as cost, limited resources and, as noted by one respondent, jurisdictional conflicts:Footnote22

"A band bylaw is created through federal legislation (Indian Act) and prosecution under federal legislation must be done by the Federal Department of Justice. However, the Federal Department of Justice [sic, Public Prosecution Service of Canada] refuses to prosecute band bylaws on the basis that the administration of justice including the prosecuting of band bylaws as set-out in 92. (14) of the Constitution Act is a provincial responsibility. In turn, the Provincial Department of Justice refuses to prosecute band bylaws on the basis that band bylaws are created under federal legislation and that it is the responsibility of the Federal Department of Justice [sic, Public Prosecution Service of Canada] to conduct prosecutions in the case of band bylaws. As the issue of jurisdiction remains unresolved, the police service is unable to enforce band bylaws as there is no prosecutorial avenue available to do so."

The police services were also asked to identify the top challenges within their communities. The following issues were identified by the respondents:

- lack of funding for salaries and benefits;

- lack of resources;

- a lack of adequate level of police officers (e.g., only one officer working in a community);

- getting funding for basic police training;

- infrastructure that does not meet building and fire codes;

- lack of suitable housing for officers;

- an absence of a clear legislative framework governing police officers;

- inadequate understanding of family dynamics related to living conditions;

- community roles for police officers beyond policing;

- abuse of substances such as alcohol and related dangerous activities such as gas sniffing;

- contraband tobacco;

- domestic violence;

- organized crime and gangs;

- addiction and mental health issues; and

- unemployment and economic development.

SA police services identified the following successesFootnote23 in their communities:

- installation of cameras in community buildings that can lead to a reduction in the number of break and enter offences;

- community police initiatives (e.g., arson prevention program);

- drug programs targeting youth;

- social navigator initiatives where people who come into contact with the police and are deemed at high risk of crime or victimization are given priority and referred to the appropriate agency;

- community programs targeting street crimes and gangs; and

- community programs involving elders, youth, and members of the wider community.

Community Tripartite Policing Agreements

Background

CTAs are tripartite agreements, involving the Government of Canada, the participating province or territory, and a First Nation or Inuit community or group of communities. As the RCMP is the service provider for CTAs, the Minister of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness is the federal signatory to these agreements. In provinces and territories aside from Ontario and Quebec, where there is not a CTA in place and where a First Nation or Inuit community does not receive policing services from a municipal or regional police service, the RCMP provides policing services to these communities pursuant to the Provincial and Territorial Police Service Agreements (PPSAs/TPSAs). Under the PPSAs/TPSAs, Provinces/Territories acquire the services of the RCMP to aid them with the administration of justice and the RCMP invoices them for 70 percent of the cost of the RCMP's services. When Provinces/Territories acquire the services of the RCMP through signing a CTA, the RCMP invoices them for 48 percent of the cost of the RCMP's services.

Unlike the case of communities working under SA agreements, communities working under CTAs have an advisory body, as opposed to a governance body, which is referred to as a Community Consultative Group (CCG).Footnote24 The CCG has no responsibilities for police governance but acts as an advisory body between the Band Council, the police, other community organizations, and members of the community. CCG members are usually volunteers who are either appointed by a First Nations Band or independently nominated by the community.

Not every community with a CTA police service has a CCG (Baidoo, Fisher, Lytle and Spelchen 2012; Jones et al. 2014). For example, Watt (2008) found that around 43 percent of the communities reported they had implemented a CCG, 43 percent indicated they had not, and the remainder did not say. It is a major challenge for many Indigenous communities to get community members to participate in a CCG. Watt noted that this was especially the case in small communities where the same individuals often volunteered on several committees and felt stretched beyond their capacity.

The CTA planning process includes a “Letter of Expectation”Footnote25 that is negotiated between the RCMP and the community. This involves asking the community what public safety-related issues they want the RCMP to make a priority and preparing a letter specifically outlining the actions to be taken over a 12-month period. In an examination of the implementation of the Letter of Expectation between the RCMP and several communities, Watt (2008, xii) found that while many of the Letters of Expectation included measurable goals and action plans, some made no reference to measurable deliverables.

The CTA sets out the roles and responsibilities of the community (or groups of communities) served, concerning the provision of a community policing facility and residences for the RCMP members. The CTAs further outline the roles and responsibilities of the provincial and federal governments concerning the monitoring of the program, and coordination of training for the CCG to ensure that the communities receive policing services that are culturally sensitive and responsive to their particular needs (Public Safety Canada, 2013). In addition, the agreement sets out the roles and responsibilities of the RCMP. Under the CTA, the RCMP uses its own human resources and financial management practices and complaints against the RCMP are handled in the same manner as in non-reserve communities - pursuant to the RCMP Act.

With respect to the RCMP, current CTAs are designed to ensure that there are officers specifically assigned to Indigenous communities, who must spend 100% of their regular working hours on the policing needs of the community. Depending on the size and location of the community and other factors, a separate police station and housing for officers may be built on the reserve. The RCMP provides its own administrative and technical support.

The OAG (2005) found that the RCMP has no time-recording system for contract policing and does not track the amount of time the peace officers assigned under a CTA spend in the community. As a result, the amount of time officers spend in the communities they serve is currently unclear (OAG 2005, 29). However, factors such as whether there is a detachment in that particular community affect the percentage of time officers are in the community. PRA (2006) noted that community members sometimes have misunderstandings concerning the amount of time policing services are available and sometimes do not take into account that peace officers may need to be out of the community for required duties such as training, court appearance, or for entitlements such as sick leave or vacation leave.

The OAG (2014) challenged the extent to which core policing servicesFootnote26 are provided by the RCMP under the CTA. The OAG noted, “In our view, the lack of clarity in the agreements and among the involved parties about what constitutes enhanced policing services—which the First Nations Policing Program is intended to fund—creates ambiguity in the delivery of those services. Furthermore, when Program funds are used for core policing services, the Program is in effect subsidizing the provincial policing services (2014, 13).”

Under the CTA policing arrangement, the RCMP operates with a full detachment, a satellite detachment, or an outside detachment. A full detachment includes officers reporting directly to a provincial or sub-provincial headquarters; it has full administrative and information system access. A satellite detachment, by contrast, refers to a physical placement of officers in communities where at least three officers are required and falls under the command of the full detachment. While full detachments may assist satellite detachments as required, crime reduction activities are primarily undertaken by local officers. Finally, an outside detachment is located outside a community, but officers are assigned to work in the Indigenous community by a detachment commander. A sub-office may be used on a reserve to assist with service provision and provide a place where concerns may be brought to police attention.

Table 4 illustrates the number of CTAs and ACCP agreements in place at the end of the 2015-16 fiscal year, including the number of communities served, the size of the population served, and the number of police officers.

| Province/Territory | Number of Agreements | Number of Communities | Size of Population Served | Number of Police Officers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

BC |

55 |

132 |

50,892 |

108.5 |

AB |

21 |

20 |

46,187 |

57 |

SK |

33 |

46 |

59,443 |

126.5 |

MB |

9 |

44 |

69,564 |

60.5 |

ON |

1 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

QC |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

NB |

2 |

2 |

4,026 |

19 |

NS |

7 |

7 |

8,529 |

40 |

PE |

2 |

2 |

621 |

2 |

NL |

4 |

4 |

2,365 |

16 |

YT |

1 |

12 |

3,666 |

16 |

NT |

1 |

10 |

5,572 |

4 |

NU |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Totals |

136 |

280 |

250,870 |

451.5 |

| Source: Public Safety Canada (2016a). | ||||

CTA Funding and Personnel

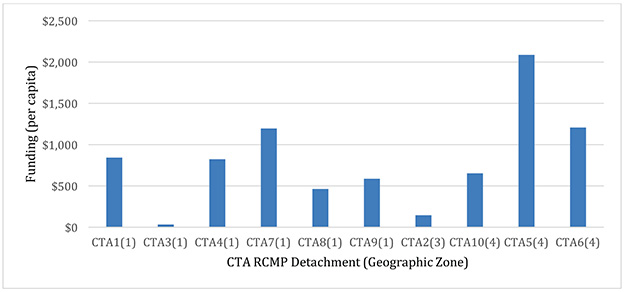

Variation exists in the funding provided to CTA detachments. To put this variation into perspective, Figure 6 displays CTA detachment funding for every inhabitant based on geographic zones (see footnote 16 for definitions of the geographic zones used). As shown, CTA5 and CTA6, which are located in remote communities, receive the greatest funding per capita ($2,086 and $1,208, respectively) whereas CTA10—which is also in a remote community—receives about half as much per capita ($652). In general, communities in remote regions cost significantly more to police than do communities located in urban or non-remote rural areas (see Ruddell and Jones 2014; Ruddell et al. 2014).

In contrast, detachments closest to urban areas should have the lowest per capita policing costs. Consistent with that observation, CTA3, which is located in geographic zone 1, has the lowest funding per capita ($32). There may be some negative outcomes for these lower expenditures, as this community has recently been in the news concerning gangs, violence, and high unemployment. Despite the fact that costs in geographic zone 1 are lower, there is still some variation in funding in the remaining four agencies (CTA4, CTA7, CTA8, and CTA9), which ranges from $586 to $1,193 per capita. By contrast, the national cost per capita for policing in 2014/2015 was $391 (Mazowita and Greenland 2016, 22).

Figure 6: Per Capita Funding in CTA Detachments by Geographic Zones

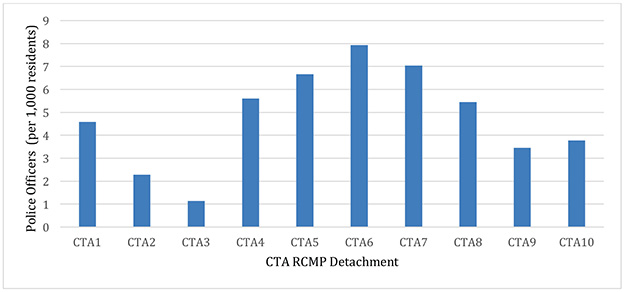

As previously mentioned, the national rate of police officers per 1,000 off-reserve residents is 1.92 officers (Mazowita and Greenland 2016). Based on the information provided in Table 4, the number of CTA and ACCP police officers per 1,000 residents is 1.80 officers. Figure 7 shows the number of CTA police officers working in Indigenous communities per 1,000 residents for the CTAs sampled in the current study. As shown, the number of officers per 1,000 residents ranges from 1.13 (CTA3) to 7.93 (CTA6), with an average rate of 4.79 officers per 1,000 residents. The number of police officers reflects the workload in particular communities. In the case of some communities, the number of officers and their workload may be related to pressures to respond to social issues, besides those related to crime, that reflect the distinct circumstances of Indigenous communities.

Figure 7: Number of CTA Police Officers per 1,000 Residents

Finally, a further review of FNPP funds allocated to the RCMP for CTAs revealed expenditures that are ineligible for reimbursement, but necessary to provide policing services under the agreements. These ineligible expenses include overtime costs for policing such as criminal investigation activities, court attendance, or the transportation of prisoners. In the 2014-15 fiscal year, ineligible expenses were around $5.3 million; for 2015-16, the estimated shortfall is expected to be about $7.4 million.Footnote27 In instances where expenses are ineligible for reimbursement under the FNPP, the PPSA/TPSA is applicable (i.e., the RCMP is reimbursed by the provincial or territorial government). For example, in 2014-15, one province reimbursed the RCMP $2.3 million for expenses that were ineligible for reimbursement under the FNPP.

CTA Police Leaders Comments

The questionnaire was completed by the 10 CTA detachments sampled. Both the questionnaire and follow-up interviews focused on the following areas:

- location of police detachment;

- police operations;

- level of policing services; and

- measuring effectiveness in their police service.

Location of Detachment

CTA detachment commanders were asked to provide their comments with regard to geographic attributes that might influence the demand for police services. Three respondents (from CTA1, CTA2, and CTA10) are located in remote “fly-in-only” communities. Two of them (CTA1 and CTA10) expressed frustration with the challenges associated with picking up prisoners from their cells, escorting them to court, and guarding them during the period they are out of their cells. Depending on the number of prisoners, there was a need to assign up to five regular officers to court duties on some court days. The respondent from CTA3 indicated that the court, hospital, and other provincial services are located in a neighbouring community, placing considerable demands on officers. Because their own support services or partnering agencies are located in their home community, what complicates matters further is that there are no provisions (e.g., access to a desk and computer) to allow officers to do other work while waiting for a prisoner to be processed or receive some kind of service. The commanding officer from CTA6 noted that taking a prisoner to a correctional facility or to receive specialized services involves travelling a distance of 454 km.

The respondent from CTA6 commented on the lengthy distance from hospitals and the substantial amount of time spent dealing with individuals detained on the basis of mental health concerns associated with an alleged crime or risk of substantial harm to self or others. This respondent noted, “once a determination is made that a person has to be viewed by a physician, that person must be taken to the nearest hospital which is 50 kilometres away. It can take anywhere from three to eight hours for the person to be examined at the hospital depending on staff work load and waiting time which removes a member from the community”.

Since getting to the nearest hospital involves a 25-minute drive, any hospital visit will involve taking an officer away from their regular community duties for several hours. Since these policing resources are spent outside the community they often result in unplanned overtime costs.

In one remote community, court is held approximately eight times a year or less often because of inclement weather conditions. Consequently, when court is held within the community, all local police resources are geared towards transporting and guarding prisoners.

Providing specialized policing services is a challenge in remote communities. In some cases, a police officer may need to protect a crime scene requiring analysis for several days while waiting for investigators with specialized skills to arrive on site with severe weather conditions sometimes a factor. The respondent from CTA2 mentioned the logistics of having police back up and other factors associated with the safety of the police officer as being a challenge in remote communities. This is a significant issue in rural policing as officers working in remote areas have a greater likelihood of death or other serious harm while carrying out their duties (Ruddell 2016). Similarly, the respondent from CTA4 indicated that all their specialized services (e.g., police dog service) are located about one hour away.

In remote communities, skilled workers who are able to fix police vehicles or make repairs to the detachment or equipment are in short supply. In these cases, the detachment members are called up to make repairs – tasks that are not normally part of their duties, but must be done. Finally, one individual (CTA8) pointed out that in their area, police can only access some of their communities by boat. This poses challenges in terms of transporting prisoners and getting access to transportation from docking sites to the community.

Community attributes such as the existence of mining and other resource extraction and processing facilities can further create challenges for these detachments. In one case, additional policing resources were required to help the local detachment control community protests. Over the year, one detachment (CTA8) indicated that there have been road blockades, “virtual blockades” (a cyberspace version of a physical sit in or blockade), and environmental protests with regard to the harvesting of shellfish and the cutting and selling of timber. Even when peaceful, these activities result in increased policing demands.

Some communities have established seasonal economies (e.g., fishing, hunting, trapping, tourism), resulting in a need for increased resources for the detachment at certain times of the year (e.g., increases in traffic, conflicts over fishing rights, illegal fishing, “waterway rage” incidents). Moreover, a greater number of tourists and other visitors increases the likelihood of search and rescue operations. The respondent from CTA3 mentioned that increased economic development in the community has resulted in an increased transient population which, in turn, increase demands on their detachments.

Finally, the officers were asked to provide some insight regarding the challenges of inadequate infrastructure in Indigenous communities. Three respondents (CTA4, CTA6 and CTA7) noted that their communities have a modern infrastructure. One officer (CTA3) noted that it is not so much a lack of infrastructure that is the problem but rather management issues, such as those involved in rent increases and the collection of rent. The respondent from CTA2 stated that there was inadequate infrastructure and housing for the members.