ARCHIVE - 2008-2009 Summative Evaluation of the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Adobe Acrobat version (PDF 600KB)

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Evaluation Issues and Methodology

- 3. Findings and Conclusions

- 4. Recommendations

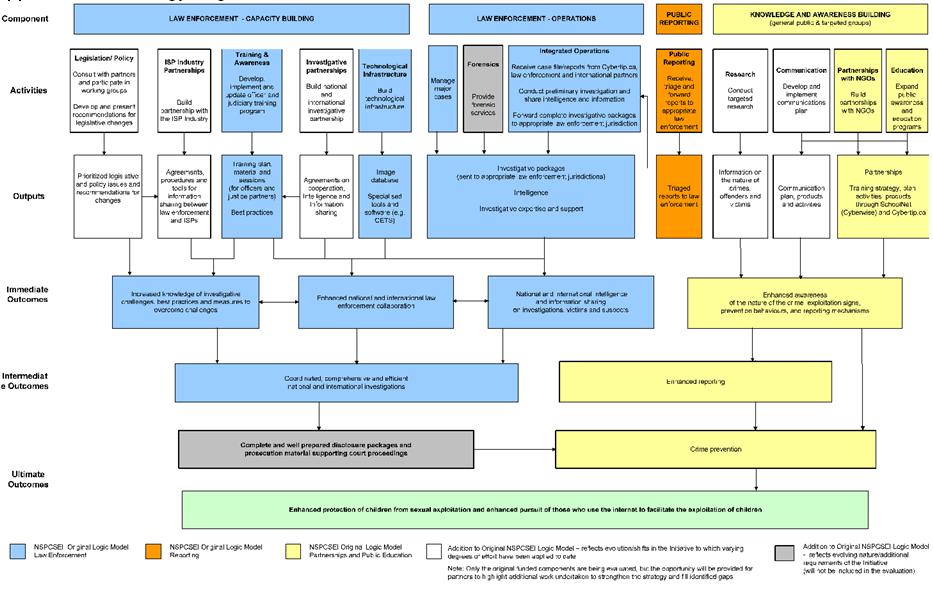

- Appendix A - Strategy Logic Model

- Appendix B - List of Documents and Quantitative Data Reviewed

- Appendix C – Interview Guides

- Appendix D – Guide for Analysis of Interview Information

| List of Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| ADM | Assistant Deputy Minister |

| AICEC | Advanced Internet Child Exploitation Course |

| C3P | Canadian Centre for Child Protection |

| CCAICE | Canadian Coalition Against Internet Child Exploitation |

| CEOP | Child Exploitation Online Protection Centre |

| CETS | Child Exploitation Tracking System |

| CANICE course | Canadian Internet Child Exploitation Course |

| CNA | Customer Name and Address |

| CWG | Cybercrime Working Group |

| ERC | Expenditure Review Committee |

| DOJ | Department of Justice |

| ESP | Electronic Service Provider |

| FPT | Federal/Provincial/Territorial |

| IBCSE | Internet-based Child Sexual Exploitation |

| IC | Industry Canada |

| ICAC | Internet Crimes against Children |

| ICE | Integrated Child Exploitation (unit) |

| INHOPE | International Association of Internet Hotlines |

| ISP | Internet Service Provider |

| IWG | Interdepartmental Working Group |

| IWGTIP | Interdepartmental Working Group on Trafficking in Persons |

| KIK | Kids in the Know |

| KINSA | Kids Internet Safety Alliance |

| NCECC | National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre |

| NCMEC | National Centre for Missing and Exploited Children |

| NGO | Non-government Organization |

| OCSET | Australian Federal Police Online Child Sex Exploitation Team |

| OIC | Officer in charge |

| P2P | Peer to peer |

| PIPEDA | Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act |

| PS | Public Safety Canada |

| PSC | Project Safe Childhood |

| RCMP | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| RMAF/RBAF | Results-based Management and Accountability Framework / Risk-based Audit Framework |

| Strategy | National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet |

| TBS | Treasury Board Secretariat of Canada |

| VIU | Victim Identification Unit |

| VGT | Virtual Global Taskforce |

| YCWW | Young Canadians in a Wired World |

[ * ] - In accordance with the Privacy and Access to Information Acts, some information may have been severed from the original reports.

Executive Summary

i) Introduction

The National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (hereafter referred to as the Strategy) is a horizontal initiative providing a comprehensive, coordinated approach to enhancing the protection of children on the Internet and pursuing those who use technology to prey on them. A total of $42 million over five years, beginning in 2004-2005, was allocated to three partners to implement the Strategy1. The table below lists the Strategy partners and summarizes the funding that was provided for each partner.

| Strategy Partner | Funding Level over Five Years |

|---|---|

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) | $34.34 M |

| Industry Canada (IC) | $3.00 M |

| Public Safety (PS) and Cybertip.ca2 | $4.70 M |

| TOTAL | $42.04 M |

Under the Strategy, the general expectations and desired achievements of each partner were as follows:

- the RCMP was to expand the current capacity of the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC);

- IC was to expand their SchoolNet Program and forge partnerships with industry and Non-government Organizations (NGOs);

- PS was to enter into a contribution agreement with Child Find Manitoba (now the Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P)) for the purposes of operating and expanding Cybertip.ca , Canada’s national tipline for reporting suspected cases of child sexual exploitation and, as the lead department for the Strategy, to coordinate, oversee and evaluate the Strategy.

Under PS lead, and through the collaboration of all partners, a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework (RMAF/RBAF) was prepared for the Strategy. During the four years since inception, Strategy activities and funding have evolved and expanded in scope leading to a progression of the initiative design that was not anticipated at the outset. For example, the $1 million in each of the fiscal years 2007-08 and 2008-09 that had been profiled for IC for CyberWise.ca activities was re-directed to PS, who, in turn, directed some of the funding to Cybertip.ca. The Strategy also received an additional $6 million per year in funding, announced in Budget 2007, to enhance existing initiatives to combat child sexual exploitation and trafficking.

PS coordinated a formative evaluation of the Strategy in 2006-073. The summative evaluation assesses the continuing relevance of the Strategy; the overall impact and success of the Strategy; cost-effectiveness and alternatives; and aspects of the design and delivery of the Strategy related to governance and progress against the recommendations of the formative evaluation. It covers a four-year period from the receipt of Strategy funding in April 1, 2004 to March 31, 2008.

ii) Summary of Conclusions

The paragraphs that follow summarize the conclusions contained in the body of this report.

- Overwhelming evidence suggests a continued need for a national strategy to combat Internet-based Child Sexual Exploitation (IBCSE). The problem of IBCSE has not diminished; rather it continues to be prevalent and expanding in Canadian society. Thus, it remains relevant and in the public interest to address this issue. Interviews and studies conclude that the Internet and technology are pervasive in children’s lives, and because of this, offenders have increased access to potential victims. Technological advancements have enabled sophisticated methods for offenders to conceal their identities and to continue to offend, leading to the emergence of new forms of IBCSE.

- The number of IBCSE cases being processed has increased, and Cybertip.caand the NCECC are forwarding more cases to law enforcement. Evidence from interviews suggests that law enforcement at the field level is lacking skilled investigators and forensics support. However, it should be noted that the responsibility for field level resources rests with provincial and municipal governments.

- The Strategy is built on a partnership approach that involves all levels of government, NGOs and the private sector. The roles and responsibilities, as they are delineated under the Strategy are appropriate. The federal government continues to play an essential role in the fight against IBCSE. Efforts of partners have been well-coordinated by PS, and the central coordinating role of the NCECC is key to a national strategy to combat IBCSE.

- Original governance mechanisms as laid out in the RMAF/RBAF have evolved. There has been no requirement for the envisioned Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) Steering Committee. The National Steering Committee is being revitalized and work of the Interdepartmental Working Group (IWG) has been well-coordinated by PS on an as-required basis. PS has also brought a degree of strategic planning to the Strategy through the redesign of the logic model, participation in national and international working groups and the development of cabinet documents to address changing needs. Further advancement of a strategic agenda and continuing to remain abreast of emerging issues is an important role of PS. There is a need for further engagement of the IWG in areas such as communications (public awareness), and research. In addition, there is still work to be done in developing awareness of other groups involved in public education efforts (outside the Strategy) so that the Strategy can realize synergies and avoid duplicating the efforts of others. Working level governance through the Integrated Child Exploitation (ICE) Officer in Charge (OIC) meetings is functioning very well although some participants would like to see longer meetings because of the significant travelling distance.

- The Strategy has been successful in increasing the knowledge of target audiences in the areas of investigative challenges, best practices and measures to overcome challenges. This outcome is directly attributable to the efforts of the Strategy. For law enforcement, training and the NCECC Annual Conference are the strongest contributors to success in this area. Raised awareness of judicial partners, such as provincial crown prosecutors, is attributed mainly to participation in the Federal Provincial Territorial (FPT) Cyber-crime Working Group (CWG). Raised awareness among Internet Service Providers (ISPs) is attributed mainly to work on Canadian Coalition against Internet Child Exploitation (CCAICE). Remaining work includes: continued training on trends in sex offender methods, Internet usage among youth and training on investigative techniques for law enforcement; education on the nature of the crime among judicial partners, and continuing awareness efforts on legal issues with ISPs.

- Law enforcement collaboration and information sharing has been enhanced a great deal through the NCECC Annual Conferences, investigative support from the NCECC, and through the building of international relationships. Information sharing has been well coordinated by the NCECC through the provision of high quality investigative packages. Limited buy-in of the Child Exploitation Tracking System (CETS) by some law enforcement agencies and the fact that the image database has not been implemented is hindering information sharing. The NCECC Technology Section continues to address detracting issues.

- Through the efforts of the NCECC and the work of Cybertip. ca, the Strategy has contributed to coordinated, comprehensive and efficient investigations. NCECC provides a single point of contact from which complete investigative packages are sent to the appropriate jurisdiction. Cybertip.ca has also realized efficiencies and taken the burden off of police by triaging complaints and forwarding complaints requiring follow-up directly to local jurisdictions. The NCECC has reduced backlog and is achieving targeted turnaround times. Despite this success, some investigations are being hindered by lack of cooperation from ISPs in providing responses to Customer Name and Address (CNA) requests which renders an investigation un-actionable.

- The work of the Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P) has greatly contributed to enhanced awareness among the general public. This is evidenced by the marked increases in reporting and educational downloads immediately following campaigns. There is evidence that children and parents are being reached because the Kids in the Know (KIK) program is being utilized in most provinces, and 15% of Canadians are now aware of Cybertip.ca as the national reporting tipline. In terms of reach, the Billy educational kit has been distributed in Ontario, Alberta, B.C. and Quebec. Evidence indicates that the kit is effective and will be used again by teachers. Limited anecdotal evidence suggests that behaviours have changed as a result of these educational efforts. Educational efforts, geared toward health care professionals and ISPs, are underway but this remains an area that requires continuing improvement. Positive results of a broad-based survey of Canadians would further solidify these findings and provide understanding as to whether awareness activities have resulted in preventative behaviours among target groups.

- Although PS has recently developed a communication plan with participation from all Strategy partners, it appears that some coordination may still be necessary between the RCMP and Cybertip.ca in terms of conducting public awareness activities. Document review indicates that there are two communications plans in existence with similar target audiences, one from the NCECC and the other the joint communication plan for the Strategy.

- From the information provided, it cannot be fully determined whether the Strategy has enhanced the pursuit of suspects; however, it would appear that some progress has been made. Anecdotal evidence indicates that, because of the Strategy, investigators are now able to complete investigations that may not have been completed prior to the Strategy. The NCECC has contributed to 34 arrests while Cybertip.ca reports contributing to 37 arrests. The NCECC statistics are based mainly on case summaries as the NCECC is not able to report on the actual number of individuals arrested as a result of the information sent to law enforcement agencies. It is probable that the figure significantly under represents the number of arrests, charges and prosecutions because many field investigation dispositions have not been completed. In addition, law enforcement agencies are not reporting back on the results of the information that was sent from NCECC.

- In terms of prevention efforts, offenders have been prevented from accessing child exploitation material through the shutting down of 2,850 websites by Cybertip.ca and through the blocking of access to 11,000 URLs through the efforts of project Cleanfeed. It cannot be determined whether or not these efforts contributed to preventing abuse of children but it can be said that it is possible that offenders and the Canadian public have been prevented from viewing offensive material.

- Protection of children has been enhanced through the identification of 233 victims. These results are not attributable solely to the Strategy since other Canadian law enforcement agencies have contributed to this result. It is also noted that Strategy partners have provided programs to help children build their self-esteem which helps to reduce their vulnerability of victimization. Protection of children could potentially be enhanced through the implementation of the image database originally envisioned as part of the Strategy, but yet to be implemented.

- There have been no major negative impacts due to the evolution of the Strategy. As the Strategy has evolved, partners have worked well together to address changing needs as they arise. The exception to this is that work on legislative issues has taken a good deal of time away from the day-to-day work of the NCECC meaning that other work has suffered as a result.

- From the information provided, it has been demonstrated that the Strategy has provided value for money to some extent. For example, monetary donations and donations in-kind have been added to Strategy resources. In 2007-08, for every dollar spent on Cybertip.ca, 41 cents in private sector donations was realized resulting in $725,000 in private sector funding. Interviewees generally believe that value has been provided, and PS and Cybertip.ca have maintained the value that was provided by IC through the proactive and efficient transfer of this file and the associated materials. Without further financial and performance information and comparable benchmarks, it cannot be conclusively stated that the Strategy overall has provided value for money.

- The Strategy has realized efficiencies. Centralized triaging by Cybertip.ca and preparation of investigative packages by the NCECC has made work more efficient for field resources. In quantifiable terms, the work of Cybertip.ca is estimated to have saved provinces and municipalities at least somewhere between $600,000 and $1,800,0004 over the last four years. The NCECC is now meeting its turnaround times. Efficiencies due to targeted research could not be quantified but interview evidence suggests that this has been the case.

- Spending of resources against budgets by Strategy partners is generally within acceptable limits with the exception of the RCMP, which has under spent its budget since 2004-05 by approximately 40%. Approximately 20% of this amount can be accounted for by the fact that the image database is delayed and funding is re-profiled each year to account for the delay. Another factor that may have contributed to under spending is the challenge of recruitment and retention across the RCMP and law enforcement, in general, and in the child exploitation area, in particular, because it is a psychologically demanding field of law enforcement specialization.

- From a review of other similar initiatives, it appears that the Strategy is a very appropriate response to the identified need. In terms of a general approach to combating IBCSE, work in other countries involves a law enforcement component and an education and awareness component, similar to the Strategy. Also, a partnership approach appears to be good practice.

- Of the initiatives studied, CEOP provides a model that may warrant further study because of the apparent benefits of an approach that is further integrated than the Strategy. Following this approach may mean integrating additional partners such as: charities that have credible understanding of victims, victim support, guidance counselors, social workers, and a youth panel. Benefits to this further integrated partnership model are seen to be the ability to use secondments to supplement resources, to receive direct support, and to receive advice and influence from varying perspectives in order to solve the complex problem of IBCSE.

- The Strategy is considered to be fully implemented, with the exception of the implementation of the image database. In addition, the majority of recommendations from the Formative Evaluation have been implemented; two of the recommendations remain to be completed.

iii) Recommendations

The paragraphs that follow summarize the recommendations put forward as a result of the conclusions drawn in the previous section.

- PS should continue its coordination activities and expand its leadership efforts. To this end, PS should further engage the IWG in coordinating activities related to communications (public awareness) and research. The strategic role of PS should be continued and strongly supported in order for the Strategy to get “ahead of the curve” on the issue of IBCSE. Thus, PS should continue to work with national and international partners to improve collaboration, share best practices and exchange ideas on child sexual exploitation on the Internet. PS should continue to advance dialogue with the provinces and territories on issues of common interest. PS should also continue to demonstrate leadership in advancing strategic planning by coordinating research to keep apprised of developments in technology, trends and emerging issues and sharing the results with interdepartmental working groups, including Strategy partners. (PS)

- Work on legislative issues has taken a good deal of time away from the day-to-day work of the NCECC meaning that other work has suffered. Given the likely continued participation of the NCECC on legislative issues and on high-profile international working groups, the RCMP should consider how they can manage resources in order to both meet these very important “upper-level” priorities and maintain leadership at the NCECC when resources may be drawn away. (RCMP)

- There is remaining work to be done in developing awareness of other groups, outside the Strategy, involved in public education efforts. To this end, PS should conduct an environmental scan in conjunction with Cybertip.ca and the NCECC to determine what other groups exist and what efforts are being undertaken by these groups in the area of education and awareness in order to realize synergies and avoid duplicating activities. (PS)

- Education efforts and awareness building activities among law enforcement, judicial partners and ISPs have proven effective in increasing knowledge among stakeholders and should continue. Continued law enforcement training needs include: training on trends in sex offender methods, on Internet usage among youth, and on investigative techniques. Training needs among judicial partners include education on the nature of the crime, and, for ISPs, increasing awareness on legal issues. (all partners)

- The Child Exploitation and Online Protection (CEOP) Centre model should be further studied to assess the benefits of incorporating additional partners, to understand CEOP’s strategic approach to “getting ahead of the issue” of IBCSE, and to assess whether parts of this approach can be applicable in the Canadian context. Recognizing that CEOP is part of United Kingdom law enforcement and as such, can apply the full range of policing powers in tackling the sexual abuse of children, but that it also has a unique structure, it is recommended that the Canadian Strategy explore possibilities of benchmarking performance information against CEOP. (PS/NCECC)

- Efforts should be made to allocate the 20% of funding that is consistently under spent by the RCMP, to forensics support for investigators. It is recognized that retaining forensic support is currently problematic for all law enforcement with heavy case loads; however, possibilities include providing a centralized forensics unit, seconding officers from other law enforcement agencies or outsourcing this function to another appropriate unit within the RCMP. It is important to note that control of the funding should remain with the NCECC to ensure that the funding is spent on Strategy activities. (RCMP)

- The NCECC should be more proactive in collecting and reporting performance information as laid out in the RMAF/RBAF (or revised version thereof) including the number of arrests, the type and number of charges laid and sentences pronounced. More work needs to be done with the field level to enable the NCECC to track this information. (RCMP)

1. Introduction

1.1 Presentation of the National Strategy

The National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (hereafter referred to as the Strategy) is a horizontal initiative providing a comprehensive, coordinated approach to enhancing the protection of children on the Internet and pursuing those who use technology to prey on them. A total of $42 million over five years, beginning in

2004-2005, was allocated to three partners to implement the Strategy5. The table below lists the Strategy partners and summarizes the funding that was provided for each partner.

| Strategy Partner | Funding Level over Five Years |

|---|---|

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) | $34.34 M |

| Industry Canada (IC) | $3.00 M |

| Public Safety (PS) and Cybertip.ca6 | $4.70 M |

| TOTAL | $42.04 M |

Under the Strategy, the general expectations and desired achievements of each partner were as follows:

- the was RCMP to expand current capacity of the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC);

- IC was to expand their SchoolNet Program and forge partnerships with industry and Non-government Organizations (NGOs);

- PS was to enter into a contribution agreement with Child Find Manitoba (now the Canadian Centre for Child Protection (C3P)) for the purposes of operating and expanding Cybertip.ca , Canada’s national tipline for reporting suspected cases of child sexual exploitation and, as the lead department for the Strategy, to coordinate, oversee and evaluate the Strategy.

Under PS lead, and through the collaboration of all partners, a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework (RMAF/RBAF) was prepared for the Strategy in order to establish accountabilities, guide performance monitoring, audits and evaluations.

1.2 Evolution of the Strategy

During the four years since inception, Strategy activities and funding have evolved and expanded in scope leading to a progression of the initiative design that was not anticipated at the outset.

For example, as per the RMAF/RBAF for the Strategy, a formative evaluation, coordinated by PS, was conducted in 2006-078, and a Management Action Plan was prepared by PS in collaboration with Strategy partners as a result of the formative evaluation. Most of the recommended changes have been made, while activities related to other recommendations are ongoing. Explanations were provided as to why some of the recommendations were deemed impossible to implement (e.g., increased resources at the field level which is a provincial or municipal responsibility).

In terms of funding shifts, in March 2007, IC informed PS that, although the operation of CyberWise.ca had two years remaining in its mandate, the SchoolNet Terms and Conditions, under which CyberWise.ca was administered, had only been extended for one year. The CyberWise.ca component of the Strategy did not include salary dollars and, with the IC Information Highway Applications Branch’s reduced funding and downsizing, it was not possible to continue support for the operation of CyberWise.ca to meet the requirements of the Strategy. Therefore, IC decided to cease its activities related to CyberWise.ca.

As the coordinator of the Strategy, PS had the authority to reallocate funding from one partner to another, if deemed necessary. PS exercised its leadership role and undertook to reallocate the IC money to Cybertip.ca to ensure the Strategy objective related to public education and awareness could be maintained. Thus, the $1 million in each of the fiscal years 2007-08 and 2008-09 that had been profiled for IC for CyberWise.ca activities under the Strategy was made available to PS, who, in turn, directed the funding to Cybertip.ca and provided for one more position at PS in the Serious and Organized Crime division.

In addition to the above-noted shifts, PS coordinated a Treasury Board Submission which detailed the allocation of the additional $6 million per year in funding, announced in Budget 2007, to enhance existing initiatives to combat child sexual exploitation and trafficking. Under PS leadership, new funds were also allocated to activities to combat human trafficking for the first time.

As a result of these developments, including the recommendations of the formative evaluation, the logic model for the Strategy was updated to reflect activities that were deemed to be important yet not anticipated at the outset of the 2004 Strategy. Those activities were undertaken by Strategy partners on their own initiative following the identification of areas where work needed to be done (see Appendix A). PS organized two one-day workshops with the evaluators and Strategy partners to discuss the revised logic model. A separation between the original logic model elements and the new elements is noted. It should also be noted that the original intent of the initiative and outcomes of the Strategy have not changed.

In terms of other assessments of the Strategy, as per the audit plan, PS coordinated an audit of Cybertip.ca in fiscal year 2006-07. This audit examined whether funds were used for their intended purposes; assessed compliance with terms and conditions; and, analyzed reliability of results data. The results of the audit concluded that Cybertip.ca funding has been managed according to recognized audit practices.

IC’s activities under the Strategy were monitored according to SchoolNet Terms and Conditions, as well as according to the objectives of the Strategy.

1.3 Purpose of the Summative Evaluation

As per the combined RMAF/RBAF for the Strategy, PS coordinated this summative evaluation and will submit its findings to the Treasury Board Secretariat (TB S) of Canada, as a basis to determine the ongoing nature and level of funding for the Strategy.

As per the RMAF/RBAF, the Summative Evaluation assessed:

- continuing relevance of the Strategy;

- overall impact and success of the Strategy;

- cost-effectiveness and alternatives; and,

- aspects of the design and delivery of the Strategy related to governance and progress against the recommendations of the formative evaluation.

This summative evaluation covers a four-year period from the receipt of Strategy funding in April 1, 2004 to March 31, 2008.

2. Evaluation Issues and Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Issues and Questions

The list that follows summarizes the research questions for the evaluation. The seven expenditure review questions of the Expenditure Review Committee (ERC) of the TBS have also been included and are referenced as such.

Evaluation Questions Relevance

- Is there a continuing need for a national strategy that combats Internet-based Child Sexual Exploitation (IBCSE)? Does the Strategy continue to serve the public interest? (ERC 1)

- Are allocated resource levels sufficient based upon the scope of the identified need, given the nature, size and evolution of the problem?

- 3. Is the Strategy appropriate to the federal government mandate and what is the appropriate role for other levels of government or the private/voluntary sector? (ERC 2, 3, 4)

Success

- To what extent has the Strategy increased knowledge of investigative challenges, best practices and measures to overcome challenges among law enforcement, justice partners and ISP providers?

- To what extent has law enforcement collaboration been enhanced through information sharing and partnerships?

- To what extent is information and intelligence being shared nationally and internationally?

- To what extent have public education efforts contributed to enhanced awareness of the nature of the crime, exploitation signs, prevention behaviours, and reporting mechanisms among the general public and target populations?

- To what extent has Strategy contributed to coordinated, comprehensive and efficient national and international investigations?

- To what extent has better awareness contributed to enhanced reporting?

- To what extent has the Strategy enhanced crime prevention?

- To what extent has the Strategy contributed to enhanced:

- protection of children from sexual exploitation;

- pursuit of those who use technology to facilitate the exploitation of children?

- How has the evolving nature of the Strategy (additional funding, additional activities undertaken, etc.) impacted the success of the Initiative?

Cost-Effectiveness and Alternatives

- Are Canadians getting value for their tax dollars? (ERC 5)

- To what extent have resources been optimised to improve efficiency? If the Strategy continues, how could its efficiency be improved? (ERC 6)

- Is the Strategy the most appropriate response to the identified need?

Design and Delivery

- Is the governance structure appropriate to achieve the Strategy's intended outcomes?

- What progress has been made toward implementation of the recommendations of the formative evaluation?

2.2 Evaluation Methodology

The evaluation used three basic lines of inquiry to complete the analysis. These were: document review, review of quantitative information and interviews. A list of documents and quantitative data reviewed by the evaluation team is contained in Appendix B. In terms of interviews, the table that follows outlines the categories of individuals who were interviewed, as well as the number of interviews conducted. Interview guides are presented in Appendix C. Throughout the report, interview information has been reported according to the guide contained in Appendix D. Thus, the terms used throughout the report associated with “a few”, “some”, “many” and “most” are specifically linked to the proportion of interviewees shown in the guide.

| Representation | Number of Interviews |

|---|---|

| Strategy Oversight | 2 |

| Cybercrime Working Group Senior Officials (DOJ) | 2 |

| Program Management – NCECC | 4 |

| International Partners | 4 |

| Program Management – Education and Awareness (IC & Cybertip.ca) | 2 |

| Law Enforcement – Field Level | 8 |

| ISPs | 3 |

| TOTAL | 25 |

2.3 Limitations and Assessment of Data Availability

The evaluation methodology was designed to provide multiple lines of evidence in support of evaluation findings. However, there were some limitations with respect to the methodologies as outlined below.

- A broad-based survey was not one of the lines of inquiry for the evaluation; the evaluation relied upon surveys previously conducted or immediately available. The evaluation also relied on measures of reach by target audience in order to assess the coverage of educational material, in place of surveying end users.

- Full analysis associated with cost-effectiveness was not possible due to several factors. First, investigations are linked through a number of levels of law enforcement (federal, provincial, municipal) and these costs could not be attributed. Second, some of the partners and activities leverage resources (financial and in-kind) from other sources and these were not quantified. Finally, benchmarks or comparables were used to the extent possible but this information was limited.

- Due to budget and time constraints, the total number of interviews was small and the sample size in each group may not have been representative of the full perspective of some target audiences. Where possible, quantitative data was used to supplement and validate the views expressed in interviews in order to mitigate this limitation.

- In terms of coverage at the field level, the evaluation covered eight law enforcement units in four general geographic regions in Canada as follows: Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, and Atlantic Canada. Saskatchewan and Manitoba did not have integrated child exploitation (ICE) units in operation at the time of the evaluation, and, although requested, the representative from British Columbia was involved in a number of operational files at the time of the evaluation and was therefore unable to participate within the timeframe of the evaluation.

3. Findings and Conclusions

Section 3 of the report presents findings from all lines of inquiry and conclusions based on the findings. It is organized according to the standard evaluation issue areas of relevance, success, cost effectiveness and alternatives, and design and delivery.

3.1 Relevance

Serving the Public Interest 9

The evaluation sought to examine whether the Strategy continues to address issues and concerns that are relevant to Canadian society and whether the Strategy continues to serve the public interest. More specifically, the evaluation examined trends regarding the continuing need for intervention by a national strategy and whether resource allocated to the Strategy are sufficient based on the scope, nature, size and evolution of the problem of Internet-based child sexual exploitation (IBCSE). Finally, the evaluation examined the appropriateness of the federal government role and its partners in the Strategy and whether there are other stakeholders, such as other levels of government or the private and voluntary sectors, which can assume responsibility for achieving some of the objectives.

Trends in Internet Use in Canada

The proliferation of Internet use in Canadian society poses an increasing risk of the exposure of children to sexual predators and potential victimization. The Internet Sexual Exploitation of Children and Youth Environmental Scan suggests that Canadians are avid users of the Internet and the trend is increasing. In 2003, data from Statistics Canada showed that approximately 64% of Canadian households reported having accessed the Internet from home, work, school a public library or other locations; this represents a 20% increase from 1999 figures. The study notes: “A cross-section of Canadian children and youth who have (and continue to) grown up in a technological world are not representative of the average Canadian’s involvement with computers and the Internet. Millions of children and youth are adept at using computers, with a large part of their time being spent on the Internet.”10 In fact, a study published in 2002, concluded that 84% of Canadian children are “wired”.

In 2000-2001, data from Young Canadians in a Wired World - Phase I (YCWW-I)13 These findings have many implications for the safety of youth and child using the Internet.

The Internet has become a fixture in the lives of today’s children and youth. Youth are integrating the Internet into their social lives at an early age. YCWW-II reported that “young people use the Internet as a social space, where they can stay connected to friends and explore social roles”.15 Nevertheless, this assumption is incorrect: a study conducted by the Adolescent Health Survey found that almost 25% of girls in Canada have been in contact with a stranger on the Internet who made her feel unsafe.

Trends in the Nature, Size and Evolution of the Problem

The NCECC conducted the Internet Sexual Exploitation of Children and Youth Environmental Scan in 2005. It concluded that Internet-based sexual crimes against children are increasing in Canada and abroad and that the public is increasingly concerned. The distribution of child sexual abuse images is also expanding, in concert with an increase in Internet use. The study states that: “while it is not possible to state empirically that the Internet has changed the demand for child sexual abuse images or if alternative means might have been exploited resulting in the same demand changes, it is possible to state that the Internet has had a large impact on the accessibility, affordability, and assumed anonymity of people seeking child sexual abuse images.”16

The study reports that while the flow of child sexual abuse images have significantly diminished in the late 1 990s, the widespread use and nature of the Internet as a medium has changed the situation.20

Effects of Evolving Technology

Due to the evolving nature of technology, the sexual exploitation of children and youth has taken on new forms. Furthermore, interconnections exist with prostitution and trafficking: “The Internet provides new tools to assist in the sale of children and youth, creates space to communicate needs of and availability of such ‘services’, and provides access to vulnerable people to victimize.”24

The emergence of botnet technology26

Advances in technology have also created easy and inexpensive, low detection means of producing child sexual abuse images: “digital cameras, scanners, and web cameras have changed the way child sexual abuse images are produced, and introduced the option to many.”28

The nature of child sexual abuse images themselves have also evolved. These images can be created using real, morphed, and virtual children. Due to technological advancements, images can be altered to generate large amounts of different depictions of children; a process referred to as morphing or creating pseudo images31

A final repercussion resulting from advancements in technology involves the widespread use of wireless technology. Wireless technology is increasingly popular way to access the Internet among individuals and businesses due to its convenience, and its affordability. It is estimated that wireless networks have increased in North America from 30 million in 2005 to 74 million by 2009.35 This makes it more difficult to locate and catch offenders. Law enforcement officers may believe to have located an offender, when in fact, they are pursuing an unsuspecting Internet user, whose wireless connection has been accessed without authorization, to access child abuse images.

Continuing Need

Most interviewees indicated a continuing need for the Strategy citing the Internet and evolving technology as drivers for the proliferation of child exploitation material. Others believed that the proportion of the population who access child exploitation material has not changed but the ability to access it has increased because of these drivers. Some interviewees indicated that the scope and nature of the crime has expanded; it is more severe, there are new forms, it is multi-jurisdictional and international in nature. Many field level interviewees have reported an increase in the number of cases and Cybertip.ca has seen an increase in the number of reports over the last four years.

Document review also provides evidence of the continuing need for educational material for parents to further protect their children on the Internet. In 2006, an Ipsos-Reid survey was conducted which revealed that: 98% of parents place a high priority on children learning how to protect themselves from sexual exploitation on the Internet; 80% of parents believe that children should learn about personal safety strategies at home and in school; most Canadian parents are using outdated and ineffective information to teach their children personal safety; a third of Canadian parents have not discussed Internet safety with their child; and the majority do not know where to access Internet safety information37.

Interviewees were also asked whether the five areas of the Strategy that were not anticipated at the outset, but are now included in Strategy activities, continue to be necessary. These five areas are as follows: Legislation/ Policy, ISP industry partnerships, Investigative Partnerships, Research, and Communications. Most interviewees indicated that all of these areas remain important. The presence of a continuing need for each of these evolving areas is presented below.

Interviewees mentioned the need to continue to study legislation in order to identify gaps and develop legislative tools and standards. They believe that when technology changes (e.g. encryption) and legislation has not kept pace, investigations are inhibited. They cited the need for mandatory compliance in providing passwords for encrypted computers and for companies, such as ISPs and computer repair shops to report child pornography if it is found on their system or on a computer. The issue of mandatory reporting is currently a high priority for the FPT Ministers Responsible for Justice. The Cybercrime Working Group (CWG), of which PS and the RCMP are active members, has been studying this issue on a priority basis over the last year. Since 2007, officials from PS and the RCMP have also been working actively on the lawful access initiative which may, if passed, assist law enforcement to further their investigations by requiring private companies to provide the Customers Name and Address (CNA) of persons suspected to be involved in illegal activities on the Internet.

Interviewees also stated that the continuing need to study legislation is evidenced by the fact that proposed legislative changes are still coming forward. Finally, interviewees stated that, with more cases going through the justice system, case law is developing, and that examination of the results of these cases may necessitate further legislative change.

Interviewees believed that ISP partnerships continue to be critical because the relationship helps to “motivate corporate responsibility in a different way”. ISP interviewees expressed that issues can be handled more effectively on a voluntary basis within set parameters through partnerships rather than through legislation. Furthermore, interviewees stated that there is a continuing need for expanding partnerships because new partners are brought in to help resolve issues as they arise. For example, they noted that Strategy partners and ISP providers are now looking at how credit card companies might contribute to their efforts. Finally, there is still work to be done, since only about 10 ISPs, out of approximately 400 in Canada, are actively engaged on the issue and are aware of the reporting tipline (Cybertip.ca). It is worth noting that these 10 ISPs have broad coverage through their networks, and cover about 90% of the country.

Interviewees believe investigative partnerships continue to be necessary for three principal reasons. First, there is a need to identify challenges and share best practices, and this is accomplished through time spent together on investigations. Second, there are large-scale, international aspects to this crime including the emergence of commercial pornography that require strong investigative partnerships. Third, more provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies are joining to address the issue; therefore further work on partnerships is anticipated.

Interviewees believe that research continues to be necessary under the Strategy to assist both educational and law enforcement efforts. There is a need to understand how Canadian children are being targeted, trends for youth and social networking, offender profiles and behaviours, and the impact of evolving technology and the approach to combating child sexual exploitation on the Internet.

Interviewees stated that it is important for the NCECC and Cybertip.ca to continue on communication efforts to ensure coordination and dissemination of best practices and to find out what is working and what is not working. In addition, a coordinated education and awareness strategy is necessary to avoid duplication of efforts. A communication strategy was produced by PS, in consultation with Strategy partners, in May 2008.

Emerging Issues

Interviewees also identified other possible program areas to be addressed by the Strategy; including judicial partnerships and forensics. Additionally, respondents felt there were other aspects of the crime which were not being addressed by the Strategy. These included the need to understand linkages between commercial pornography and child sex tourism since proceeds of crime falls under the federal mandate but child pornography offences are prosecuted provincially; the involvement of organized crime; and understanding the needs of victims. A few interviewees suggested that having international presence as part of the Strategy could help address problems with child sex tourism. This would involve having an international task force located at the NCECC and active units in other countries to target Canadian citizens travelling for the purposes of child sex tourism. To this end, a new position was recently created at the RCMP to address the issue of child sex tourism.

Resource Demands38

The evaluation studied whether resource levels are sufficient based on the scope of the identified need, given the nature, size and evolution of the problem of IBCSE.

Document review indicates that the child pornography industry is expanding, a problem exacerbated by widespread use and availability of the Internet. Criminal Justice statistics support the finding that the incidence of production and distribution of child pornography and luring children via computers has increased. Furthermore, evidence shows that perpetrators are adults as well as other youth. A study conducted by the NCECC presents a summary of these findings:

| Number of Child Pornography and Luring Offences in Canada39: | |

|---|---|

| 1998 (per 10,000 adult and youth population) | 2005 (per 10,000 adult and youth population) |

| 0.006 | 0.042 |

| Number of Adults and Youths being Processed through the Court System for Child Pornography Offences40: | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults (per 10,000 adults) | Youth (per 10,000 youths) | ||

| 1998-99 | 2003-04 | 1998-99 | 2002-03 |

| 0.042 | 0.091 | 0.012 | 0.044 |

Efforts and workload trends among law enforcement suggest that the problem is getting worse. Many field level interviewees cited investigative resources as their most pressing need stating that they are unable to meet demand to investigate and process cases that they are receiving. Cybertip.ca statistics support these findings. The statistics indicate an increasing number of cases forwarded to local law enforcement. Between 2002 and 2004, 191 cases were forwarded to local law enforcement agencies; in 2005, 203 cases were forwarded; in 2006, 324 and in 2007, 437 cases were forwarded to provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies41. It should be noted that the responsibility for field level resources rests with provincial and municipal governments.

Some interviewees identified the lack of an image recognition database and forensics software and personnel as serious impediments to their operations. They cited the need for trained forensics personnel and a desired increase in forensics resources that would see a ratio of one forensics resource for every two investigators. They indicated that lack of forensics resources presents challenges as investigators prepare for court because they do not have enough time to put their cases together both because forensics work is time consuming (size of files being processed is sometimes in terabytes) and due to the backlog in forensics, because of limited resources. Filling positions in forensic analysis would be a provincial/municipal responsibility.

In terms of resourcing the demand for educational material, downloads reported by Cybertip.ca suggest an increase in public requests for education and awareness material. Statistics reveal that the number of Cybertip.ca educational downloads have significantly increased. Between 2002 and 2004, 20,038 downloads were made, increasing to 120,541 downloads in 2007. Cybertip.ca has also tracked the distribution of awareness material. Between 2005 and 2007, the following material has been distributed: 195,463 books and comics, 228,914 safety sheets, 3,161,215 brochures, 29,558 posters and 31,121 kits.

Conclusions – Serving the Public Interest / Providing Resources to Meet the Need

- Overwhelming evidence suggests a continued need for a national strategy to combat Internet-based Child Sexual Exploitation (IBCSE). The problem of IBCSE has not diminished; rather it continues to be prevalent and expanding in Canadian society. Thus, it remains relevant and in the public interest to address this issue. Interviews and studies conclude that the Internet and technology are pervasive in children’s lives, and because of this, offenders have increased access to potential victims. Technological advancements have enabled sophisticated methods for offenders to conceal their identities and to continue to offend, leading to the emergence of new forms of IBCSE.

- The number of IBCSE cases being processed has increased, and Cybertip.ca and the NCECC are forwarding more cases to law enforcement. Evidence from interviews suggests that law enforcement at the field level is lacking skilled investigators and forensics support. However, it should be noted that the responsibility for field level resources rests with provincial and municipal governments.

Roles and Responsibilities/ Governance42

The evaluation explored whether the roles of federal partners in the Strategy are appropriate, whether other levels of government, private or voluntary sectors should be involved in the Strategy, and if the current governance structure is appropriate to achieve the Strategy’s outcomes.

The Strategy is built on a partnership approach that involves all levels of government, NGOs and the private sector. Formal funding is provided to two federal partners, PS and the RCMP, and an NGO, Cybertip.ca through a contribution from PS. However, the Strategy also includes donations to Cybertip.ca from the private sector, including ISPs. Although not funded under the Strategy, provincial and municipal police agencies investigate child exploitation files through the ICE units and local police agencies. Interviewees generally believe that federal partners, the RCMP and PS, in conjunction with Cybertip.ca, each play the appropriate role with regard to the Strategy.

PS led the [ * ] coordinated activities of partners during the preparation [ * ] and the coordination of audits and evaluations. Between 2004 and 2008, PS also coordinated and prepared responses to over 50 Ministerial dockets on behalf of partners, has coordinated two formal evaluations of the Strategy, and an audit of Cybertip.ca activities. PS is the “federal face” of the Strategy for FPT working groups such as the Coordinating Committee of Senior Officials - Cybercrime Working Group and the National Coordinating Committee on Organized Crime. PS has also provided input to related TB submissions outside the Strategy such as the lawful access initiative and PIPEDA. In terms of developing and maintaining positive relations with provincial partners, both PS and the RCMP play a key role in FPT fora to exchange information, discuss effective techniques to combat child sexual exploitation, as well as discuss legislation. PS also co-chairs the Interdepartmental Working Group on Trafficking in Persons (IWGTIP) which allow for effective engagement of eighteen federal departments & agencies that share an interest in child sexual exploitation and trafficking.

In terms of the RCMP’s role, the central coordinating role of the NCECC, on the law enforcement side, is considered a very important aspect of the Strategy that needs to be maintained going forward mainly because the NCECC provides a single point of contact nationally and internationally. Close to half of interviewees believe that little or no overlap exists between the law enforcement area of Strategy and other programs (the other half did not comment). Rather, they noted that other law enforcement bodies such as local law enforcement agencies, ICE units, provincial strategies and the Virtual Global Taskforce (VGT) complement the work achieved through the Strategy.

In terms of Cybertip. ca ’s role, interviewees were generally positive about the role Cybertip.ca has undertaken both in managing complaints and providing educational material. However, interviewees also expressed uncertainty regarding the level of duplication or coordination of educational efforts related to this role. Cybertip.ca and many other groups appear to be involved in the educational area. For example, presentations in schools are being provided by law enforcement officials, school liaison officers, guidance counsellors and other organizations such as Kids Internet Safety Alliance (KINSA).

Finally, interviewees suggested further engagement of provincial and municipal governments and other organizations, including grassroots and voluntary sectors, ministries of health, child protection services and school boards. Other federal departments were also suggested for further engagement in the Strategy, these departments include the Department of Justice, Statistics Canada, Canada Borders Services Agency, the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade and Citizenship and Immigration Canada43.

Horizontal Level Governance44

The RMAF/RBAF for the Strategy outlined several mechanisms for oversight and horizontal governance. First, PS’s role was to a) support the ADM Steering Committee in terms of policy coordination, development and logistics; and b) provide overall coordination for the implementation of the entire Strategy. Second, according to the original design, the Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) Steering Committee was seen as necessary to provide overall direction, oversight and advice on events and circumstances that may influence the achievement of expected outcomes. Third, partners were to work collectively through an Interdepartmental Working Group (IWG) to measure, monitor and report on performance and risks against expected outcomes and to maintain Strategy corporate memory in support of knowledge management46.

Over half of those interviewed indicated that, generally, the current governance structure for oversight works well or causes no concerns. Overall, interviewees felt that there is no need for an additional level of decision-making such as an ADM Level Steering committee as PS briefs the upper levels when necessary. However, a few interviewees departed from this point of view stating that having upper level involvement would help drive the issue of IBCSE from a government-wide perspective. To this end, following the formative evaluation, PS coordinated the management response and reaffirmed its commitment to revitalizing a National Steering Committee to provide direction and guidance to Strategy partners. In May 2008, a meeting was held with partners (PS and RCMP) to determine the level of representation for the steering committee; it was determined that the Director General/Superintendent level would be the most appropriate.

Coordination and Strategic Direction of the Strategy

In terms of providing strategic direction to the Strategy, PS has assumed this role, and through coordination of the IWG, a revised logic model was developed in 2008 to include some activities that were not part of the original Strategy. PS also recently led the development of a communications plan for 2008-2009 to assist in coordinating education and awareness activities in consultation with RCMP and Cybertip.ca. The plan sets out communication objectives for the fiscal year of 2008-2009. Document review indicates that there may still be coordination work to be done since the NCECC also has a communications plan with some shared target audiences and similar activities. A few interviewees noted that the Strategy may be able to increase cohesion through better coordination of strategic direction between the RCMP and Cybertip.ca. In addition, a few interviewees mentioned the coordination role of PS as being appropriate; however, they believe that the Strategy requires further and engagement of the IWG to coordinate such activities as: implementation of the communications plan; legislative issues and how work on this file should divided among partners, including DOJ; and to help integrate a research agenda because the NCECC, Cybertip.ca and PS are all involved in research.

Some interviewees made suggestions that they believe could make the Strategy more effective in responding to changing needs and emerging issues. The increased coordination of research efforts (noted above) would benefit this forward planning work. On-going progressive research was noted as being important to help the Strategy by providing a broader understanding of the crime and the current technological context, and by regularly challenging the assumptions on which the Strategy is built. This research could provide deeper insight into the issues of how offenders interact on the Internet and why they use the Internet to commit their crime. For example, the Wickerman investigation47 found that the motives were not about organized or commercial crime but rather; about individuals sharing images for “kudos”. Studying successes such as the Wickerman case and others at the tactical level could translate into action at the strategic level and could assist the Strategy in further realizing success.

Working Level Governance

Some interviewees commented that roles and responsibilities are clearly defined, positive working relationships exist and partners are engaged in discussions. Relationships appear to be built successfully on an informal basis, but may benefit from meeting more frequently to improve the decision-making process. To this end, partners have worked collectively through the Interdepartmental Working Group (IWG) as the need arises. Performance information received from the NCECC, in particular, for the evaluation has been weak.

At the field level, interviewees support that working level coordination is working well or that there are no particular issues with the governance structure. ICE Officer in Charge (OIC) meetings were viewed as being the greatest contributor to the success of governance at the working level. These meetings were seen as useful for communication, planning and sharing of information on the law enforcement side of the Strategy; issue resolution; communicating what is happening; and making decisions on investigative issues. For example, from the interviewees’ perspective, these meetings were an opportunity to discuss case law decisions and to help ICE units with understanding the role of the NCECC in these situations and to discuss the potential role of the NCECC in streamlining business and procedural matters. Interviewees noted that other meetings and committees that have contributed to working level governance include the CETS working group, international working groups, and the Victim Identification working group.

Interviewees suggested the following: holding longer ICE OIC meetings (significant distance to travel for a short time period) and potentially link them to the annual conference, and; invite Crown prosecutors and other relevant players such as heads of education to the ICE OIC meetings to provide an opportunity to share key information and clarify roles.

Conclusions – Roles, Responsibilities and Governance

- The Strategy is built on a partnership approach that involves all levels of government, NGOs and the private sector. The roles and responsibilities, as they are delineated under the Strategy are appropriate. The federal government continues to play an essential role in the fight against IBCSE. Efforts of partners have been well-coordinated by PS, and the central coordinating role of the NCECC is key to a national strategy to combat IBCSE.

- Original governance mechanisms as laid out in the RMAF/RBAF have evolved. There has been no requirement for the envisioned Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) Steering Committee. The National Steering Committee is being revitalized and work of the Interdepartmental Working Group (IWG) has been well-coordinated by PS on an as-required basis. PS has also brought a degree of strategic planning to the Strategy through the redesign of the logic model, participation in national and international working groups and the development of cabinet documents to address changing needs. Further advancement of a strategic agenda and continuing to remain abreast of emerging issues is an important role of PS. There is a need for further engagement of the IWG in areas such as communications (public awareness), and research. In addition, there is still work to be done in developing

awareness of other groups involved in public education efforts (outside the Strategy) so that the Strategy can realize synergies and avoid duplicating the efforts of others. Working level governance through the Integrated Child Exploitation (ICE) Officer in Charge (OIC) meetings is functioning very well although some participants would like to see longer meetings because of the significant travelling distance.

3.2 Success

Section 3.2 presents findings related to the achievement of desired outcomes of the Strategy. The degrees of success in the areas of law enforcement and education/awareness, as well as the impacts on success due to the evolving nature of the Strategy are presented in the sections that follow.

3.3.1 Law Enforcement Capacity Building and Operations

The objectives of the Strategy have a very wide reach and a number of law enforcement beneficiaries. Under the Strategy, through the work of the NCECC, it was intended that municipal and provincial law enforcement agencies across the country would benefit from increased coordination, as well as investigative and intelligence assistance. Under the Strategy, it was also intended that the NCECC would foster particularly close relationships with the ICE units and specialized units in other police services. Finally, the NCECC was intended to be the primary point of contact for international investigations concerning IBCSE cases and would liaise with international police forces to the benefit of both Canadian law enforcement and law enforcement abroad.

Impact of the Strategy on Knowledge and Awareness among Law Enforcement, Justice Partners and Internet Service Providers 48

The NCECC has been proactive in providing training for the increased knowledge of investigative challenges, best practices and measures to overcome challenges among law enforcement, justice partners and ISP providers. This has been accomplished through the hosting of training sessions and national conferences, the sending of communiqués and website hosting.

Conferences have contributed to knowledge increase for several of the target groups. From 2004-2007, the NCECC hosted the NCECC Annual Conference. These conferences were an ideal venue for investigators from across Canada to share investigative techniques, promote best practices and network. Over the years, the NCECC Annual Conference consistently increased participation of investigators. Approximately 130 participants representing 64 investigative units in the area of IBCSE were expected at the 2007 law enforcement workshop50. For every year of the conference, ratings of at least 4.5 out of 5 or above (5 indicating strongly agree) were given on the statement that the conference provided an opportunity to learn.

In 2008, the Atlantic Region Internet Safety Symposium was held by the NCECC to provide a better understanding about the scope of IBCSE and reinforce the need for law enforcement, government and ISP co-operation. The symposium expanded the breadth of participants and subject matter went beyond that of law enforcement topics to include: youth issues, learning about U.S. Electronic Service Providers (ESP), information on mandatory reporting initiatives, and ISP partnership initiatives. Participant feedback indicated that the symposium provided a good opportunity for discussion and a better understanding of the judicial process from complaint to court. Overall, results indicated that the Symposium allowed participants to gain a better understanding of IBCSE and to learn about U.S. ESP initiatives and the need for cooperation among industry, government and law enforcement.

Awareness among Law Enforcement

All law enforcement interviewees indicated that law enforcement knowledge has been increased due to the Strategy, mainly in the area of investigative and legal challenges. Specific knowledge acquired includes: increased knowledge of the Criminal Code; increased knowledge of reporting; age of consent; mandatory reporting; and increased knowledge and awareness about the crime in general. Interviewees noted several benefits of gaining this knowledge: the ability to support less experienced law enforcement; having unique knowledge in areas such as the luring sections of the Criminal Code; and the improved communication between stakeholders and the subsequent improvement of cooperation.

Interviewees noted that NCECC training, conferences and speaking venues contributed the most to the increase of law enforcement knowledge. Opportunities to network and educational materials were also mentioned. This was supported by other stakeholders, with training being identified as the most significant contributor to knowledge increase for law enforcement. Areas for further development for law enforcement include more focus on investigative and legal challenges, training on how to identify a hands-on offender and increased information on ISPs.

In the Formative Evaluation51, interviewees spoke of the need to have properly trained personnel in the area of child sexual exploitation. To respond to these needs, the NCECC developed two Internet Child Exploitation Courses, the Canadian Internet Child Exploitation (CANICE) Course and the Advanced Internet Child Exploitation Course (AICEC). As of the end of 2006-2007, cumulatively, over 200 officers were trained via these courses. As well, in 2006-2007, the NCECC developed a training video for first responders with the Ontario Police Training Video Alliance and the NCECC delivered the Covert Internet Course to 20 candidates. In addition, the NCECC works with its partners to offer the P2P Workshop, with approximately 50 officers having received this training. Investigators also suggested that Lawful Justification and C24 training be provided, and subsequently five officers have been trained as of June 2007.

The course feedback summary from the March 2007 CANICE course indicated that this course was successful in expanding law enforcement knowledge of the investigative process when dealing with Internet child exploitation cases. The candidates indicated that they were taught hands-on skills in a controlled environment, and that they benefited from the exposure to different methodologies employed by the different agencies represented on the course (RCMP, OPP, municipal police forces and Crown prosecutors).

Feedback has also been collected on the NCECC communiqué and website. The NCECC communiqué is designed to update partners on the strategic direction of the NCECC and provide updates on operational files52. The majority of participants provided positive feedback and agreed that the Communiqué provides valuable and interesting information that they proactively forward to others. Feedback on the NCECC website was also positive with 79% of participants familiar with the NCECC website. The website was noted as being useful for preparing presentations to new members, accessing investigative success stories, and for research and development purposes.

Awareness among Judicial Partners

Judicial partners interviewed indicated that their knowledge has increased the greatest in the area of law enforcement best practices, mainly through the FPT Cyber-crime Working Group meetings, in which PS and the RCMP are active members, and the NCECC sponsored conferences. However, with the quickly changing environment, one interviewee noted that the judiciary should be trained in the area of technology. Other areas for future training were noted as follows: sentencing (some inconsistencies among provinces); education on the crime (40-80% of people who collect pornography will act on their fantasies); and technology (interpretation of the Internet as being a public space). However, it was noted that finding experienced trainers would be a challenge and the interpretation of the CNA tool remains to be set in case law.

Awareness among ISPs

ISP interviewees noted that their knowledge has increased mainly with regard to understanding investigative and legal challenges as well as measures to overcome challenges, particularly with regard to the CNA tool. ISPs noted that they are now more aware of what Crown prosecutors do with this type of information, and how it is used in a case. The Canadian Coalition against Internet Child Exploitation (CCAICE)53, in which PS and the RCMP are active players, is a multi-sectoral collaboration group that was seen as a benefit to ISPs. PS and the RCMP have had the opportunity to improve collaboration and advance discussion with ISPs through the FPT Cyber-crime Working Group. As well, other opportunities provided by the NCECC for information exchange were seen as helping to increase knowledge. Other interviewees noted that ISP knowledge has increased as a result of the Strategy, mainly through CCAICE and conferences. Law enforcement noted that this increase in knowledge has contributed to a cooperative relationship between themselves and ISPs. However, interviewees noted that a focus on legal issues such as use of the CNA tool and civil liability assurances needs to continue. At the moment, ISPs are often declining to provide a customer name and address to law enforcement due to fears of civil liability, thereby affecting the working relationship between ISPs and law enforcement. As well, one ISP noted that since smaller ISPs are still providing limited cooperation, they need a better understanding of law enforcement challenges which may be achieved through the recent approach to regional ISPs to participate in CCAICE. Finally, ISPs noted that they require clarification on their role when local child welfare and community agencies are involved in the case.

Moving Forward: Potential Areas of Improvement

National training needs are continually assessed by the NCECC. The NCECC has recognized gaps from feedback forms submitted by candidates, and content is currently being revised to improve all courses, as well as identify new training needs. As well, feedback received at the Internet Safety Symposium indicted that there is a need to develop further awareness, training and communications strategies to inform the public on the prevalence of IBCSE and to enhance stakeholder partnerships, particularly with ISPs, and develop partnership with victims and youth. Potential areas of training include54: the prevalence of the type of Internet usage in relation to children (e.g., Facebook, MSN); sex offender trends (new tools and software); luring investigations; interview techniques; and more information on the VGT.

Impact of the Strategy on Law Enforcement Collaboration and Information/ Intelligence Sharing55

Inception documents of the Strategy clearly outline the intended benefits of working in partnership. The documents indicate that because each complaint may implicate multiple suspects across jurisdictions, coordination among federal, provincial and municipal enforcement, as well as internationally, is very important. Interviewees were asked if activities implemented under the Strategy have had an effect on law enforcement collaboration and information/intelligence sharing. Specifically, interviewees were asked to comment on the impact of conferences and training; investigative tools, such as CETS and image databases; working in partnership; and investigative support from the NCECC. Document review was used to supplement interview findings.

Conferences and Training

Many of those interviewed stated that the working relationship and information sharing among law enforcement has been enhanced through conferences and training. Many field resources mentioned that the NCECC Annual Conference is an important forum for getting to know people personally. They cited the most significant benefit of attending the annual event to be the fact that they were able to “attach a face to a name” and know who to call directly for information. Other noted benefits of the conferences were the ability to share information and best practices,

bring everyone up to speed, build capacity, identify gaps and discover common solutions. Interviewees further indicated that attendance at conferences and training helps those working in the field develop standardized terminology which facilitates communication and information sharing. Finally interviewees indicated that the conferences themselves provide a real-time opportunity to share information and actually work on cases together in the same location.

Document review supported these findings. The “ability to network” was the predominant theme from participants who completed feedback forms for the NCECC Annual Conference from 2004, 2006, and 2007. Participants were asked to rate whether “This workshop provided the opportunity to network”. This statement consistently received a rating of between 4.7 and 4.9 on a scale of 1-5 57. “Information sharing/learning” was the predominant theme for 2005 where participants included comments such as: “I have a vast list of people to call to assist me in an investigation. We can put faces to names and this is easier to communicate later.”

CETS and Investigative Tools

Many field interviewees indicated that CETS has provided little enhancement to their working relationships or to information sharing and that there are outstanding issues. They expressed the hope that CETS would be stronger in the near future, but also stated that usability, cumbersome access (e.g., too many passwords), time-consuming data entry, and the fact that CETS is not universally adopted by Canadian law enforcement have been issues. Others stated that CETS will not work with their databases. Some see the CETS tool as a burden in terms of data entry, but thought that retraining may help people understand that taking a few minutes to enter data will provide vital information.

Interviewees expressed concern that the less CETS is used, the larger the gaps in investigations, because information that could be shared is not in the system. Some believed that Canada is lagging behind other countries on the technological side, both in terms of CETS and the image database, which has not yet been implemented. To this end, some expressed that they are currently using C4P to categorize images in place of having a national database that would more consistently categorize images on a national basis. Others noted the use of GROOVE, in place of CETS, as a secure place to share investigative information.

Document review was somewhat contradictory to these finding. Statistics indicate that, as of February 2008, CETS had 287 trained users and 24 of 32 agencies were regularly contributing to CETS. As a result, the system contained 5,156 investigations and 11,789 pieces of online identity information58. The few field level interviewees that are using CETS noted the benefit that they can share information and connect quicker with others who are using CETS.

Investigative Support from the NCECC

About half of interviewees believe that investigative support from the NCECC has enhanced their working relationships and improved information sharing. They stated that the NCECC provides a positive international liaison and national connection point that did not exist four years ago. There was an appreciation that the NCECC provides a focal point for information sharing so that less duplication of effort is occurring; the proper jurisdiction is handling files; and investigators can now share information with all parts of the country through the NCECC if they choose. Interviewees also expressed that confidence and trust with the NCECC has increased. The investigative packages that they receive from the NCECC are more complete and actionable, and that investigations are now moving forward. Others stated that they are now receiving high quality investigative packages in a timely manner, noting that the NCECC used to have a six month backlog, and that now there is no backlog.