Youth At-Risk of Serious and Life-Course Offending

Risk Profiles, Trajectories, and Interventions

Youth At-Risk of Serious and Life-Course Offending PDF Version (792 KB)

Youth At-Risk of Serious and Life-Course Offending PDF Version (792 KB)

ISBN: 978-1-100-17843-1

Table of contents

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Externalizing Behaviours

- Interventions in Theory

- Risk Profiles of Distinct Young Offender Groups and Intervention Approaches to Mediate Associated Risk Factors

- Conclusion

- Reference List

Executive Summary

One of the enduring criminal justice policy issues facing most democratic governments is the reduction of serious and violent offending by both youth and adults. While it is not yet evident whether there has been a reduction in the continuity of offending from adolescence into adulthood in Canada, comparative research from England overwhelmingly confirmed this continuity (Farrington, 2002). In effect, two related major crime prevention policy challenges are how to reduce the levels of adolescent and adult serious offending and how to disrupt the criminal trajectory linking child delinquency, serious adolescent criminality, and serious adult criminality. Since the 1990s, there has been a substantial increase in research confirming the importance of well known risk factors for serious and violent young offenders. In addition, there has been a concomitant increase in the evaluations of intervention programs designed to reduce risk factors. This report reviews the most recent literature that identifies the range of risk factors, the developmental patterns of risk factors, and highlights appropriate age-stage intervention approaches for youth with varying risk profiles.

Part of the success of more recent interventions can be attributed to the development of more sophisticated risk assessment instruments. These instruments range from brief screenings for specific risks, such as sexual aggression, to comprehensive instruments designed to identify life-course risk factors. While the related concepts of risk and protective factors for antisocial behaviours is well established, there has been a recent emphasis toward explaining the inherently complex interaction between risk and protective factors. Another major shift in research on serious and violent youth was the emergence of bio-psychological risk factors. While much of this research remains tentative, it has very important implications for both the identification of additional and possibly critical risk factors, as well as the development of new intervention strategies that could be implemented very early on in the life-course and at later stages of development.

This report is based on a review of relevant risk factors that must be taken into consideration when applying interventions to prevent, reduce, or respond to youth at risk of serious and life-course offending. Discussion of these risk factors is presented in the format of pathway models that are hypothesized to illustrate the clustering of risk factors among distinct groups of young offenders. These groups are believed to be qualitatively different from each other and while they may exhibit several similar behavioural problems, these problems are experienced differently among the different types of youth and thus must be targeted differently. The key assumption of these models is that there are various groups of young offenders who present with different “causes” of antisocial behaviour. Effective and sustained reductions of antisocial behaviour in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood require interventions that address these causal risk factors, as opposed to behavioural outcomes associated with these causes.

Risk Factors Associated with Antisocial Behaviour in Youth

Several of the important traditional and new risk factors for serious and violent offending are environmental factors that occur during the earliest developmental stages (e.g., maternal substance abuse, community disorganization, residential mobility, exposure to violence, family socioeconomic status). Other risk factors associated with antisocial behaviour in children and adolescents relate to the individual. These include executive dysfunction (e.g., difficulty connecting actions and consequences, adapting to new circumstances, processing information to set and realize goals), chronic under arousal and abnormal biochemical activity. Similarly, psychological factors, such as cognitive delays/disorders (e.g., ADHD), certain personality traits (e.g., conduct disorder), poor coping ability, and poor school functioning, have been linked with delinquency and later serious and violent offending. Family risk factors are important for understanding and predicting antisocial behaviour and violence (e.g., maternal education and IQ, parental antisocial practices and attitudes). Finally, various externalizing behaviours, such as early deviant behaviours, violence, aggression, and substance use, as well as general behavioural problems have been identified as strong predictors of future antisocial behaviour.

Proposed Pathway Models and Intervention Approaches

Pathway A: Prenatal Risk Factors

This pathway begins with prenatal damage from factors, such as prenatal alcohol consumption, toxicity, and poor prenatal diet. Without initial effective interventions, this pathway consists of early and persistent aggressive behaviours which increase the onset of subsequent developmental stage related risk factors through adulthood. Interventions targeting pregnant women to promote healthy pregnancies, proper maternal diet, and absence of substance abuse also play a crucial role in reducing the likelihood of prenatal risk factors.

Pathway B: Childhood Personality Disorder

This pathway begins with a childhood personality disorder, such as conduct disorder or opposition defiant disorder. Children in this pathway develop unstable bonds with their parents and caregivers. In the absence of early interventions for these childhood personality disorders, early bullying behaviour and other major behavioural problems occur in the school environment. Unlike those in the prenatal pathway model, these individuals do not have social and academic difficulties because of cognitive dysfunctions, but because of opposition to authority and low discipline.

Early interventions focus on providing the family with support and information to understand the specific personality disorder and how to respond verbally and behaviourally. School interventions also focus on discipline as well as positive and non-stigmatizing rewards. For children in this pathway, it is important to professionally identify any co-morbid disorders, and devise intensive individual and family intervention plans typically involving child psychologists, and family physicians where medication is required. Beyond family and school information interventions, organized and supervised school and community-based sport and recreational activities provide positive or prosocial alternatives.

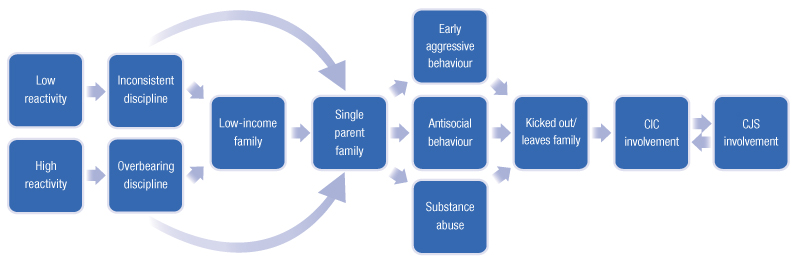

Pathway C: Childhood Temperament

This pathway begins with either extreme irritable and aggressive child temperament traits or extreme passive traits evident as early as 4 months of age. One concern is that positive bonding between infant/child and parent(s) is hindered by these two extreme temperament profiles when parents do not respond appropriately. In effect, a long-term strained communication relationship between parent and child relationship is set in motion which then increases the likelihood of either internalizing or externalizing behaviours. The focus of intervention is on infancy and the toddler age periods where clinical diagnosis can identify the extreme temperament types. Parent awareness is the first step to understanding the importance of how to respond to a child to facilitate preventive promotive factors. During the early childhood stage, teachers can provide the in-class individualized attention that will avoid the early school experiences becoming a major source of anxiety for high reactive students or boredom/frustration for low reactive students. Regular teacher-parent contacts, head start home focused programs, and sports and recreation programs are structured resources that can assist parents in lessening the misunderstanding of child temperaments which can increase the risks that result in them either being kicked out of or leaving home during the late childhood and early adolescent stages as well as being placed in multiple care placements.

Pathway D: Childhood Maltreatment

This pathway begins with early childhood maltreatment from birth to five years of age. Beyond the obvious risk of possible permanent brain damage, the major risk associated with maltreatment is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) at any age. This pathway is distinctive primarily because it is first based on the earliest possible incidents of maltreatment, and second, the high likelihood that the maltreatment is either completely undetected or detected long after it has facilitated additional risk factors for serious and violent offending in later developmental stages. Intervention strategies for this pathway focus first on identifying families at high risk for child abuse. Family doctors, walk-in-clinic doctors, emergency doctors and nurses, social workers, day care workers, and police are potential sources of identifying the most egregious infant and toddler maltreatment cases while pre-school and kindergarten teachers can assist in the early childhood stage.

The early identification of high risk families for child abuse is the first step in providing the at-risk child with protection by assisting the family with resource supports that substantially reduce the likelihood of maltreatment. Where the risks remain too high despite such assistance, child care options outside the family are the next intervention. Where major maltreatment has occurred, the latter interventions need to be followed by the complete diagnostic analysis that identifies developmental problems, particularly those associated with brain damage. Early childhood stage interventions also focus on providing major maltreated and traumatized children with secure, trusting, and persistent adult relationships in contexts other than just the home. This pattern is the essence of intervention programs through the remaining childhood and initial adolescent stage. Most importantly, clinically-based and validated programs to treat PTSD are available. Again, the key to this pathway is to identify early trauma related to maltreatment to avoid further trauma by making the initial trauma the intervention priority.

Pathway E: Adolescent Onset

This pathway is the most prevalent among young offenders, but not as pervasive among serious and violent offenders. The dominant theory is that this developmental stage is the inherently difficult physical and emotional transition phase to young adulthood. There is a significant number of youth whose risk factors are concentrated in the adolescent stage, and who continue serious and violent offending into adulthood stages. Most interventions for this pathway involve traditional programs, including education upgrading, trade skills training, cognitive-based therapies, independent living experiences, and apprenticeships. A major objective is to provide youth with prosocial alternative lifestyle options. Again, a major theme of this pathway is that youth choose a criminal lifestyle which involves serious and violent offending because it provides them with a sense of belonging to a group, status, protection, income and excitement. Interventions have to provide the opportunities for realistically obtainable lifestyles that meet, at least, most of these youthful imperatives.

Conclusion

A key theme in this report is that there are multiple pathways to offending and, therefore, there is the need to consider multiple intervention strategies. The five pathway-intervention strategies have many over-lapping or shared risk factors and interventions. However, there are fundamental differences in the timing of the interventions in terms of developmental stages and the primary “causal” risk factor(s) to be addressed. Most encouragingly, it has been possible to begin incorporating specific programs to reduce the likelihood of individual or sets of related risk factors identified for each pathway. Cumulatively, the specific programs are hypothesized to reduce the likelihood of an individual completing the specific pathway to serious and violent offending.

Introduction

One of the enduring criminal justice policy issues involves the reduction of serious and violent offending. In Canada, it was in the early 1960s when the federal Minister of Justice asked why adult federal prisons were filled with so many inmates who previously had been through the rehabilitation-based juvenile justice custodial institutions. Replacing the old Welfare model based Juvenile Delinquents Act, 1908 with the Young Offenders Act, 1982 (YOA) and with the subsequent Youth Criminal Justice Act, 2002 (YCJA) was intended in part to address this problem. It is noteworthy that continuity of offending has been identified as a pervasive problem across young offender samples into adulthood. For example, analysis of the first 40 years of the Cambridge Study data indicates a considerable continuity in offending from adolescence to adulthood at age 40 (Farrington, 2002) and the trend of continuity has similarly been observed by other researchers and in other countries (e.g., Blumstein, Cohen, Roth, & Vishner, 1986; Wolfgang, Figlio, & Sellin, 1972).

During the last decade, there has been a substantial increase in research confirming the importance of risk factors for serious and violent young offenders such as an early onset of delinquent activities, and persistent school problems. In addition, there has been a concomitant increase in the evaluation of intervention programs designed to reduce risk factors, including meta-analytic studies which quantify the effect sizes (i.e., reduction of targeted negative outcomes) of types of programs. There also has been an increase in support for developmentally based intervention strategies, i.e., strategies that are age- and development-stage specific. In response to the increased understanding of both the numerous risk factors and the distinctive patterns of the interaction of many of these wide-ranging risk factors that influence each individual's propensity for serious and violent offending, there has been a revisiting of the need to resort to ethically and multi-sectoral, and resource intensive case management, approaches.

This report examines the recent literature on the range of risk factors, the developmental patterns of risk and protective factors, and effective age-stage intervention approaches to prevent, reduce, or respond to antisocial behaviours in children and youth. Discussion of risk factors is presented in the format of pathway models that are hypothesized to illustrate the clustering of risk factors among distinct groups of young offenders. These groups are believed to be qualitatively different and while they may exhibit several similar behavioural problems, these problems are experienced differently among the different types of youth and thus must be targeted differently. The key assumption of these models is that there are various groups of young offenders who present with different “causes” of antisocial behaviour. Effective and sustained reductions of antisocial behaviour in childhood, adolescence, and adulthood require interventions that address these causal risk factors, as opposed to behavioural outcomes associated with these causes. General externalizing behaviours associated with serious and violent young offending will first be discussed, in addition to necessary considerations related to interventions targeting such behaviours.

Externalizing Behaviours

Behavioural problems have been found to be relatively stable and evident by three years of age yet not until later developmental stages do they tend to become more serious, less responsive to intervention, and more likely to become chronic (Lane, Gardner, Hutchings, & Jacobs, 2004). Both early antisocial behaviour and previous antisocial behaviour have been identified as strong risk factors or predictors of future antisocial behaviour (Hemphill et al., 2006). In one study, 55% of young offenders had committed an antisocial act in the previous year, and this prior antisocial behaviour was one of the strongest predictors of criminal behaviour (Margo, 2008). Specifically, prior theft was one of the strongest aggravating risk factors predicting a high probability of future theft (Farrington et al., 2008).

Early antisocial behaviour has been identified as an important risk factor for continued antisocial behaviours. For example, children who are disruptive in kindergarten have been found to be at an increased risk of frequent antisocial behaviour as they age (Lacourse et al., 2002). Additionally, recent research indicated that anti-normative behaviours among older school aged children are a useful predictor of antisocial behaviour. In particular, having been suspended; expelled, or truant in the past year were strongly associated with adolescent offending (Margo, 2008) and high truancy in late childhood and early adolescence were risk factors for violent behaviour (Farrington et al., 2008). Additionally, bully behaviour has been found to correlate with truancy, poor academic achievement, school drop-out and several other factors associated with antisocial behaviour (Nishina, Juvonen, & Witkow, 2005; Wolke et al., 2000).

Truancy is of interest, as truant youth, especially in socially disorganized neighbourhoods, have been identified as more likely to engage in substance abuse even after controlling for several risk factors, including school performance, antisocial attitudes, parental monitoring and association with delinquent peers (Henry & Huizinga, 2007). Further, youth suspended from school have been found to be more likely to engage in antisocial behaviour within 12 months of their suspension (Hemphill et al., 2006), which, may be partly explained in relation to the increased time spent with antisocial peers during the forced absence from school. Running away from home has been identified as a predictor of violent behaviour for adolescent boys (Farrington et al., 2008), while girls who run away tend to be more likely to suffer from substance abuse problems and to engage in gang culture; however, these behaviours may pre-date leaving the family unit (Kempf-Leonard & Johansson, 2007). As well, girls who turn to antisocial lifestyles including prostitution, theft, forgery, and fraud were more likely to do so to survive on the streets or as a result of pre-existing vulnerabilities related to previous traumatic abusive experiences. Once on the street and engaged in the antisocial lifestyle, this became a risk factor for serious and violent offending, most obviously in formal gang or more informal group contexts (Kempf-Leonard & Johansson, 2007).

Early aggressive behaviour has been one of the best predictors of later serious antisocial behaviour. Specifically, the level of aggression at age eight was among the best predictors of criminal events by 30 years of age (Huesmann, Eron, & Dubow, 2003). Children with the highest levels of aggression in kindergarten have been identified as the most likely to follow a path of chronic violence (Nagin & Tremblay, 2001). After having identified individual-level risk factors (e.g., IQ, hyperactivity, anxiety levels) and parental risk factors (e.g., education of parents, age of parents at birth of first child, SES) that differentiated children into several behavioural trajectories, the most powerful predictor of membership in the high aggression trajectory was the child's level of hyperactivity and opposition in kindergarten (Nagin & Tremblay, 2001). Additionally, violence in childhood or adolescence has been identified as one of the best predictors of future violence (Farrington et al., 2008). While not all children who display early aggressive behaviours are prone to become antisocial adults, most serious and violent offenders have been found to have experienced childhoods characterized by extensive misbehaviour including physical aggression (Wasserman & Miller, 1998).

Interventions in Theory

There is consensus among researchers that certain interventions are effective for certain types of moderate to less serious risk factor profiles. However, there is disagreement concerning the ability to identify appropriate and validated interventions for serious and violent young offenders. There have been considerable variations among countries in the willingness to experiment, to some degree at least, with less than completely validated interventions targeted at the risk factors for serious and violent offenders. Similarly, it has been asserted that it is the inherent complexity of the number of risk and promotive factors that has inhibited the necessary development of policies and programs needed to reduce the numbers of serious and violent offenders or, at least, mitigate their criminal trajectories early (Robinson, 2004). This complexity is reflected first, in the multiple levels that incorporate the numerous risk and promotive factors, and, second, in the difficulty in isolating and intervening with any single risk factors at any one level given that there are few direct or simple hypothesized causal patterns. The remainder of this report will address proposed pathways to young offending with differing “causes” to illustrate the need for targeted interventions that address the multiplicity of risk factors.

Risk Profiles of Distinct Young Offender Groups and Intervention Approaches to Mediate Associated Risk Factors

Pathway A: Prenatal Risk Factors

Image Description

This figure illustrates Pathway A: risk profile of children exposed to prenatal risk factors. It shows that prenatal exposure to various risk factors, such as fetal alcohol syndrome, cigarette smoke or other toxins, maternal stress and poor diet during pregnancy, is associated with multiple CIC placements, poor school performance, greater drop-out risk, relationships with antisocial peers—which in itself exacerbates performance and drop-out problems—early substance abuse, aggressive and risk-taking behaviours and, lastly, involvement with the criminal justice system, which also leads to multiple CIC placements.

Exposure to various risk factors prior to birth may impact the ability of the child to develop within healthy ranges in-utero. Further, the impacts of exposure to one or more of these risk factors may continue to affect development through later childhood and adolescence, thereby impacting the likelihood of engaging in prosocial childhood, adolescent, and adult behaviours. Young offenders who have been exposed to prenatal risk factors and have experienced multiple placements in the children in care (CIC) system at an early age are hypothesized to represent a distinct group of individuals facing unique developmental challenges that impair their ability to respond effectively to risk factors experienced later in life. This section will provide a brief overview of prenatal risk factors and outline the impact of exposure to one or more of these risk factors on subsequent development and antisocial tendencies.

Types of Prenatal Risk Factors

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) is caused by prenatal consumption of alcohol and is associated with physical growth developmental delay, learning problems, and mental health problems throughout the life-course (The Assante Centre for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, 2005). Approximately 30% of youth on probation orders in Canada have FASD or are considered to be high risk for FASD (The Assante Centre for Fetal Alcohol Syndrome, 2005).

It is well established that prenatal alcohol consumption causes FASD, however research is emerging to suggest that it may also be associated with an increased risk of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD; Mick, Biederman, Faraone, Saye, & Kleinman, 2002), but this link remains tentative and requires further research (Linnet et al., 2003). Research is also emerging to suggest that prenatal exposure to other toxins ingested by pregnant women may impact development. In particular, ingestion of cigarette smoke in-utero has been associated with later behavioural problems. In particular, prenatal exposure to smoke has been associated with conduct disorder and ADHD (Thapar et al., 2003; Wakschlag et al., 1997) in addition to an increased likelihood of impaired ability to learn to moderate aggressive behaviour, which has been associated with increased risk for serious and violent behaviour (Tremblay et al., 2004). Not surprisingly, prenatal smoking has also been linked to violent and non-violent crime (Brennan, Grekin, & Mednick, 1999; Green, Gesten, Greenwald, & Salcedo, 2008).

Prenatal stress has been found to be predictive of serious and violent behaviour as well. Mothers who experienced severe anxiety during the late stages of pregnancy were found to be twice as likely (10%) to have children with behavioural and/or emotional problems by age four years (O'Conner, Heron, Golding, Beveridge, & Glover, 2002). Elevated stress levels during the late stages of pregnancy have also been associated with increased risk of ADHD in boys and emotional and behavioural problems in both boys and girls (Brouwers, van Baar, & Pop, 2001; Huizink, de Medina, Mulder, Vissere, & Buitelaar, 2002; O'Conner et al., 2002). Additionally, poor nutrition during pregnancy has been related to the development of antisocial behaviour (Raine, 2004). Very low birth-weight has been identified as placing babies at a heightened risk of low IQ (minus 12-14 points), developmental delays, and behavioural problems as compared to babies born at full term (Luu et al., 2009). Low birth-weight has been correlated with premature birth which, for example, in Canada constituted 8.1% (290,000) of all births in 2006-2007. Premature birth has been found to be more common among teenage mothers, those with hypertension, and lower SES individuals (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2009), all risk factors for antisocial behaviour.

Impact of Exposure to Prenatal Risk Factors on Behaviour

There is preliminary support for the relationship between exposure to prenatal risk factors and early placement in care, as evidenced by research linking FASD and entry into care. Research from Saskatchewan indicates that 72% of children with FASD were placed in care at some point in their lives (Habbick, Nanson, Snyder, Casey, & Schulman, 1996). These children tend to enter into care at an early age (i.e., two years) and typically remain in care for an average of five years (Habbick et al., 1996). Further, many of these children are exposed to multiple placements in care (Habbick et al., 1996). Research on an American sample indicated similar trends, in that many children with FASD were placed in care by three years of age either in response to concerns over the welfare of the child or at the request of the mother (Ernst, Grant, Streissguth, & Sampson, 1999). Another American study indicated that children with FASD are placed in care significantly more frequently and are more prone to having learning and social needs (Kvigne et al., 2004). It has been suggested that the increased propensity to remove FASD children from their homes may be related to increased likelihood of parental substance abuse, which may place the children at increased risk for abuse and neglect, thereby resulting in placement in care (Kvigne et al., 2004).

Children exposed to prenatal risk factors may be more likely to experience difficulties in school. While FASD may result in learning difficulties, so too may birth complications, as these complications are associated with brain damage resulting in low IQ. This may hinder school success, as IQ is associated with general factual knowledge, vocabulary, memory, abstract thinking, social comprehension, and judgment. Individuals with low verbal IQ have been found to be more likely to have difficulty expressing themselves, remembering information, and engaging in abstract thought, each of which are important to succeed in the classroom (Agnew, 2008). In the absence of a supportive and consistent living environment, children who have been exposed to prenatal risk factors may have difficulty overcoming limitations associated with low IQ and may fail to excel in the classroom. This would not be surprising, as it has been found that boys with lower IQ were more likely to have poor school performance (Koolhof, Loeber, Wei, Pardini, & D'escury, 2007).

School performance may also be impacted by the presence of a learning disability, which may also result from prenatal exposure to risk factors. Learning disabilities including dyslexia (impaired reading ability), dyscalculia (developmental arithmetic disorder), and dysgraphia (impaired written expression), have been associated with substantial academic difficulties which then increase the likelihood of disruptive disorders in childhood, and later antisocial behaviours (Sundheim & Voellere, 2004). This is a concern as poor academic performance has been identified as a significant risk factor for antisocial behaviour (Hemphill et al., 2006). In a sample of incarcerated youth in British Columbia, only slightly more than half of the youth were enrolled in school at the time of the offence, and many of the youth were already at least one academic year behind other students their age (Corrado et al., 2008). Additionally, using a sample of secondary school students in the Netherlands, a general relationship between misbehaviour in the classroom and general antisocial behaviour has been observed (Weerman, Harland, & van der Laan, 2007). However, this association should be interpreted cautiously, as approximately one-third of youth who misbehaved in school did not engage in antisocial behaviour elsewhere (Weerman et al., 2007).

Since youth who were exposed to prenatal risk factors are at a heightened risk of residential mobility and poor school performance, they may resort to association with antisocial peers. According to Haynie and South (2005), residentially mobile adolescents may be more likely to associate with antisocial peers and to adopt the behaviours of their peers once they join new groups, as it may be easier for the youth to be accepted into a negative, rather than positive, peer group. Peer acceptance and relationships are classic key factors in criminological theories related to deviant childhood and adolescent development including early youth gang membership (Cohen, 1955; Decker, Katz, & Webb, 2008; Klein & Maxson, 2006; Kvaraceus & Miller, 1959). Involvement in a delinquent peer group throughout adolescence has been associated with increased violent behaviours. While removal from such groups has been associated with a corresponding decrease in violent behaviours, early and prolonged exposure to delinquent peers has been found to have long-lasting impacts on the development of persistent patterns of antisocial behaviour (Lacourse, Nagin, Tremblay, Vitaro, & Claes, 2003). Additionally, a reciprocal relationship has also been identified whereby delinquent youth were attracted to delinquent groups which then increased the likelihood of the substantial escalation of serious and violent offending especially in gang structures (Elliott & Menard, 1996; Gatti, Tremblay, Vitaro, & McDuff, 2005; Thornberry, Lizotte, Krohn, Farnworth, & Jang, 1994; Thornberry, Lizotte, Krohn, Smith, & Porter, 2003a).

In the company of antisocial peers and poor behavioural controls that result from prenatal exposure to risk factors, these youth may be more likely to engage in early substance abuse because they are more prone to impulsive and risk-taking behaviours. Substance abuse has been a traditional risk factor for antisocial behaviour; even marijuana use has been identified as one of the strongest aggravating risk factors for violence (Farrington et al., 2008). These youth may also resort to aggressive or bully behaviours. A relationship between prenatal risk factors and bully behaviour has been identified in terms of behaviours of youth with ADHD. Individuals taking prescribed medications for ADHD were found to be at an increased risk of becoming both bullies and victims of bullies. This relationship between bully behaviour and ADHD has been explained by low self-control; however, it did not explain the association between victimization and ADHD (Unnever & Cornell, 2003). It is likely that the increased propensity to engage in aggressive behaviours antagonized other violent youth who retaliated (Unnever & Cornell, 2003).

As evidenced by research to-date, exposure to various risk factors at the prenatal stages of development may result in developmental challenges at later stages of life and an impaired ability to mediate future exposure to risk factors. This may result in a unique stacking of risk factors that place these individuals at a heightened risk for engaging in serious and violent antisocial behaviour.

Recommended Intervention Strategy

Interventions to prevent prenatal risk factors must be designed to reduce exposure to risk factors through prenatal education. Interventions to respond to those suffering the effects of exposure to these risk factors must consider the distinctive patterns of neurocognitive damage for each youth as opposed to more generic interventions typically utilized for other impulsive disorders. These interventions to-date, have initially emphasized culturally sensitive family (biological and foster) support in addressing early childhood learning deficits and externalizing behaviours. As well, early decisions regarding removal from the biological family may minimize the likelihood that parent(s) of FASD children will respond by ignoring the infant's bonding and emotional needs. These parents must also be cautioned against permitting or participating in displays of externalizing behaviours, and aggressive or violent outbursts that may cause further neurocognitive damage, emotional trauma, or negative socialization. Without initial effective interventions, this pathway consists of early and persistent aggressive behaviours which increase the onset of subsequent developmental stage related risk factors through adulthood. Interventions during the next developmental stages have concentrated in facilitating structured home and school environments for the child by providing in-home service assistance, and targeted school curricula and teaching. Income, health, housing and employment assistance in late adolescence and early adulthood are often necessary to mitigate the continued high exposure to later stages' serious risk factors.

Pathway B: Personality Disorders/Aggressive Disorders

Image Description

This figure illustrates Pathway B: risk profile of children with personality or aggressive disorders. It shows that early presence of personality disorders or aggressive traits in children, such as psychopathic tendencies, is associated with unstable living situations and inconsistent parental discipline, which can result in early bully behaviours and poor school performance. If combined with any related criminal family behaviour, these two factors may in turn contribute to multiple CIC placements, which leads to involvement with the criminal justice system.

The presence of early child personality disorders or a cluster of aggressive traits may amplify the impact of other risk factors, particularly those related to parenting practices, thereby culminating in a stacking of risk factors that place the youth at an increased risk of engaging in serious and violent antisocial behaviour. It is hypothesized that these youth represent a distinct group of young offenders who face a unique set of risk factors impacting their ability to develop prosocial behavioural repertoires. This section will provide a brief overview of personality disorders and aggressive traits and will outline the impact of these disorders and traits on subsequent development and antisocial tendencies.

Personality Traits/Disorders

A strong relationship has been observed between personality disorders among youth and antisocial behaviours. In particular, conduct disorder has been closely related to antisocial propensity, as it negatively impacts prosocial development and places children at increased risk of engaging in antisocial behaviour. While conduct disorder has been criticized for being too broad of a diagnostic construct (as defined by varying levels of aggressiveness and antisociality) to explain serious and violent antisocial behaviour (Frick & Dickens, 2006), conduct disorder has remained a strong predictor of violent behaviour even after controlling for other critical risk factors (Hodgins, Cree, Alderton, & Mak, 2007). Support for the relationship between conduct disorder and other related personality disorders with antisocial behaviours is evident in the results of a recent meta-analysis reporting that a large proportion of youth in juvenile detention and correctional facilities were diagnosed with conduct disorder (Fazel, Doll, & Långström, 2008). Further, personality disorders, including traits associated with oppositional defiant disorder and other behavioural problems such as ADHD and externalizing problems, not uncommonly, pre-dated arrests (Hirshfield, Maschi, & Raskin White, 2006).

Psychopathic traits are associated with callous, deceptive, unemotional behaviour, and a pervasive disregard for the wellbeing of others. While still controversial when utilized to explain serious and violent youth, psychopathy nonetheless has been identified as a strong predictor. For example, one Canadian study involving interviews with incarcerated youth and follow-up of their criminal records after an average of 14.5 months, indicated that level of psychopathy in boys was a robust predictor of general and violent recidivism (Corrado, Vincent, Hart, & Cohen, 2004). However, the predictive accuracy associated with the measure of psychopathy in this study was mainly related to the behavioural traits as opposed to the interpersonal or affective traits assessed. An additional follow-up analysis at 4.5 years provided further support for the hypothesis that level of psychopathy in adolescent boys was a strong predictor of recidivism (Vincent, Odgers, McCormick, & Corrado, 2008). While psychopathy is not reversible, children displaying psychopathic traits or behaviours associated with other childhood personality disorders may benefit from a highly structured environment to modify associated behaviours.

Impact of Personality Disorders/Aggressive Traits on Behaviour

The impact of a child personality disorder may be compounded by unstable living situations. In particular, households characterized by violence and chaos may not provide the developing child with a personality disorder the structure necessary to overcome the barriers associated with the disorder. Domestic violence often takes place in the presence of children, and this may intensify the negative outcomes associated with residing in a chaotic environment. For example, one study found that children also were present in nearly half of all cases of domestic violence where police were called. In 81% of these cases, the child directly witnessed violence, and was disproportionately exposed to weapons, mutual assault and substance abuse (Fantuzzo & Fusco, 2007). The impact of exposure to this abuse is evident in the recent finding that children between the ages of 6-18 years whose mothers experienced abuse, were significantly more likely to have internalizing (i.e., anxiety, depression, withdrawal), externalizing, and total (i.e., overall) behavioural problems than children whose mothers were not abused (McFarlane, Groff, O'Brien, & Watson, 2003).

When in a chaotic residential environment characterized by violence, parents of children displaying early aggressive tendencies associated with personality disorders may be more likely to apply inconsistent and progressively harsh parenting techniques. Support of this relationship is found in the recent findings of the association between harsh parenting styles, aggression and conduct problems were higher as early as ages 2 (Snyder, Cramer, Afrank, & Patterson, 2005; Benzies et al., 2009). More specifically, parental corporal punishment has been found to be related to behavioural problems at 36 months up until the first grade (Mulvaney & Mebert, 2007). Parenting style has been found to further increase the likelihood of antisocial behaviour. Longitudinal research involving a sample of children aged 5-21 years reported that children physically abused in the first five years of life were at greater risk of being arrested in adolescence for violent, non-violent, and status offences (Lansford et al., 2007).

Children with personality disorders are by definition more likely to present with authority conflict behaviours. Coupled with the negative impacts associated with exposure to violence, these children may be more likely to act out in school and emulate the behaviours modeled before them at home by engaging in bully behaviours at school. The likelihood of this progression may increase as family members engage in additional antisocial behaviours, as supported by the recent finding that antisocial attitudes of parents, particularly, parental attitudes towards fighting, have been predictive of adolescent aggressive behaviour even after controlling for the attitudes of the adolescents themselves (Solomon, Bradshaw, & Wright, 2008). More generally, antisocial behaviours of all family members, particularly those of the father, have been found to predict antisocial behaviours of youth (Farrington, Jolliffe, Stouthamer-Loeber, & Kalb, 2001; Alltucker, et al. 2006). The association between parental antisocial tendencies and parenting practices is evident in the recent finding that parents who had been incarcerated were more likely to employ ineffective parenting strategies. The negative impact of these ineffective parenting practices was likely confounded by mental illness and substance abuse (Dannerbeck, 2005; Blazei et al., 2008).

It is important to note that while these youth engage in bully behaviours and experience poor school performance similar to those exposed to prenatal risk factors, the source of these issues remain distinct. In contrast to those exposed to prenatal risk factors, children with personality disorders do not perform poorly in school as a result of learning disabilities or engage in bully behaviour as a result of frustration and poor behavioural controls; instead the behaviours of these youth are motivated by general oppositional attitudes, such as a tendency to engage in disruptive behaviours and a disregard for rules and authority. These attitude problems become particularly problematic for the individual if placed under the care of child protective services. As these youth continue to behave poorly in school settings and exposure to violence continues, these youth may be more likely to come to the attention of child protective services. Likelihood of removal from the parental home may mount as family members engage in additional antisocial behaviours. However, due to their difficult behavioural profiles, once placed in care, these youth are likely to experience several placement shifts as caregivers express an inability to care for them (Newton et al., 2000). While placement in care has been found to be a risk factor of early start delinquency (Alltucker et al. 2006), placement instability (i.e. multiple shifts among CIC placements) has been found to compound this risk (Newton et al. 2000).

As the personality disordered youth experiences more of these risk factors, each preventing him/her from benefiting from the structured environment required to learn to moderate aggressive tendencies, the individual becomes more likely to engage in serious and violent antisocial behaviours. While these youth may experience many of the same risk factors experienced by those exposed to prenatal risk factors, these risk factors are experienced differently by the two groups. As such, the personality disordered youth represents a distinct type of young offender, requiring unique and targeted interventions.

Recommended Intervention Strategy

There are multiple intervention points for this pathway depending on the type of personality disorder, and the type of family dysfunction (profile of risk factors) present. During the early child stage, childhood disorders often become evident through various sources including parents, daycare, pre-school, kindergarten schools and social workers. Early interventions focus on providing the family with information to understand the specific personality disorder, and how to respond verbally and behaviourally. Typically, the latter involves setting limits to acting out behaviours with non-violent explanations to the child, and immediate and consistent consequences (e.g., time-outs, and loss of privileges). School interventions also focus on discipline as well as positive and non-stigmatizing rewards. For example, it is critical to avoid imparting negative identity labels e.g., 'stupid', 'crazy' and 'weird', by teachers, students and family members in responding to the acting out behaviours. Kindergarten teachers also are important in identifying the extreme expressions of these childhood disorders (Moffitt, 1993). For children in this pathway, it is important to professionally identify any co-morbid disorders, and devise intensive individual and family intervention plans typically involving child psychologists, and family physicians where medication is required. In the extreme cases, child psychiatrists provide the specialized treatment interventions located usually in major children's hospitals (see for example: BC Children's Hospital, 2009).

For the middle childhood stage (7-10 years) and late childhood stage (11-12 years), behavioural problems associated with childhood disorders are manifested not only in the home and school contexts but increasingly in neighbourhood contexts and with antisocial peers including older youth. Bullying, vandalism, truancy, minor theft, cigarette and/or marijuana smoking, alcohol consumption, early sexual activity, street focused peer activities during the evening and night, forming informal gangs with older youth, and, far more infrequently, minor connections with formal gangs usually distributing drugs in and around schools, indicate the need for several intervention strategies depending on the configuration of these (often associated) antisocial behaviours. Again, beyond family and school information interventions, organized and supervised school and community-based sport and recreational activities provide positive or prosocial alternatives. For the more serious combination of risk factors, innovative community-based programs provide both immediate diagnostic, referral planning and access to appropriate government and non-government agencies' resources (see for example: Child Development Institute, 2009). In effect, an integrated intervention strategy is required for children in this pathway stage to mitigate the likelihood that they will move to the next adolescent developmental stage where far more serious and violent behaviours can become entrenched.

In the latter stage, the family and especially the school, remain important sources of intervention programs. Poor school performance and school dropout are major risk factors and therefore, programs that respond to making school a more positive experience are necessary. Again non-stigmatizing and culturally specialized (e.g., Aboriginal) remedial programs attenuate these risk factors (Corrado & Cohen, 2002; Corrado et al., 2008). While “alternative schools” provide concentrated teaching resources and a more positive learning context for multi-risk factor youths, several concerns remain. Most importantly, is the concentration of high risk for serious and violent adolescents and their further isolation from prosocial peers. Youth justice system programs are essential resources for those adolescents who have become potential and actual young offenders, serious or not. For either type, the non-youth criminal justice system integrated diagnostic in-take approach for all youth potentially in conflict with the law, for example as utilized in Quebec since 1977 (see LeBlanc and Baumont, 1992), provides an effective intervention strategy for the wide range of risk factors exhibited in the adolescent stage. By assessing the initial likely presence of these risk factors and providing referrals to agencies that provide specialized interventions, most youth are more likely to avoid the negative labelling effects of the youth justice system while still accessing resources that likely mitigate their current risk factors. Again, the interventions are designed to prevent any escalation or repetition of serious and violent offending.

Pathway C: Extreme Child Temperament

Image Description

This figure illustrates Pathway C: extreme child temperament profile. Extreme temperament can present itself as a personality characterized by poor reaction or, on the contrary, by heightened reaction. Faced with these behaviours, parents may react by being too permissive or too strict. Communication problems in relationships between parents and children with extreme temperament are exacerbated in low-income or single-parent families. As the children get older, it can result in early aggressive behaviour, antisocial behaviour and substance abuse, which can lead to getting kicked out of or leaving the family home. These are followed by multiple CIC placements and involvement with the criminal justice system.

Individuals tend to present with a particular temperament from a very early age, and this temperament may result in a cycle whereby individuals shape their behaviours to the temperament of the child, thereby reinforcing behaviours associated with that temperament. If parenting practices are too yielding to the child's temperament, the child may not effectively learn to moderate behaviour and may become prone to antisocial outbursts. A brief discussion of child temperament and associated risk factors for antisocial behaviour will be provided below.

Extreme Child Temperament

Temperament has been explained as a “historical product of genetically influenced reactions accommodating to particular sequences of experiences” (Kagan & Snideman, 1999, p. 856). In particular, two qualitatively distinctive temperaments — uninhibited and inhibited — have been identified, and these temperaments have been found to be associated with infant and mother, other intimate and non-intimate relationships throughout adolescence and into adulthood. Children with low reactivity tend to be shy, quiet, cautious, or timid in interactions, and emotionally reserved in expressing feelings or when confronted with unfamiliar social events. In contrast, in similar circumstances, high reactive children tend to be talkative, spontaneously affectionate, and, at least initially, trusting (Kagan & Snideman, 1999).

Impact of Extreme Child Temperament on Behaviours

This pathway begins with either extreme irritable and aggressive child temperament traits or extreme passive traits evident as early as four months (Kagan, 2004). One concern is that positive bonding (e.g., secure attachment) between infant/child and parent(s) is hindered by these two extreme temperament profiles when parents do not respond appropriately, and instead, negative bonding patterns (e.g., insecure avoidant and insecure hostile) occur. In effect, a long term strained communication relationship between parent and child is set in motion which then increases the likelihood of either internalizing (self-destructive) behaviours or externalizing (aggressive and violent) behaviours. For example, children who have low reactivity to people generally, and, therefore do not respond with typical positive behaviours (e.g., smiling and affection) to their parents, can increase the likelihood that the parents presume the child requires less attention and discipline. Some parents, therefore, adopt an excessively permissive parenting style from the beginning where the child learns little (non-normative) social discipline, most importantly, the ability to delay gratification through self-regulation. In contrast, those parents who respond to high-reactive children with excessive discipline in an attempt to set limits and guidelines inhibit the ability of their children to learn to respond to novel and challenging social relationships with the curiosity and confidence normatively required to establish positive relationships (Keenan & Shaw, 2003). These failures to positively communicate during the infant and early childhood stages are more associated with low SES (Hoff, 2003; Huttenlocher et al., 2007; Pan et al., 2005) and the related factors of single parent and exacerbated parental stress (Hay et al., 2003).

Unlike the childhood disorder pathway, this pathway does not focus on specific combination of traits that constitute personality disorders but rather the more general and far fewer temperament traits. In other words, it is assumed that temperament types are more pervasive risk factors among children than personality disorders even though there are certain traits from the former that are associated with the latter especially in the adolescent and early adulthood developmental stages when the full range of personality disorders are present. For example, low reactivity temperament is associated with the psychopathic personality disorder, and the high reactivity temperament can be linked to narcissistic and borderline personality disorders. Another difference between the two pathways is that fewer risk factors are identified in the Child Temperament pathway. Arguably, this pathway also is more prevalent and therefore, needs to be addressed in terms of intervention strategies.

Recommended Intervention Strategy

The focus of intervention is on infancy and the toddler age periods where clinical diagnosis can identify the extreme temperament types. Parent awareness, especially for multi-risk single parents, is the first step to understanding the importance of how to respond to a child to facilitate preventive promotive factors. Again, beyond educating parents about avoiding over-controlling, harsh, inconsistent or lax forms of discipline, there are specialized psychiatric-based programs (mentioned above), including training manuals, for those infants and toddlers who present with extreme manifestations, and parents who lack the individual and family resources to respond to the specific temperament type. During the early childhood stage, teachers can provide the in-class individualized attention that will avoid the early school experiences becoming a major source of anxiety for high reactive students or boredom/frustration for low reactive students. Again, it is important to avoid the negative initial school experiences which increase early aggressive behaviours, antisocial withdrawal, or late childhood or drug use, each a risk factor for poor school performance. Regular teacher-parent contacts, head start home focused programs, sports and recreation programs are structured resources that can assist parents in lessening the misunderstanding of child temperaments which can increase the risks that result in them either being kicked out of or leaving home during the late childhood and early adolescent stages as well as being placed in multiple care placements. Many of the programs mentioned in the previous pathway can be utilized for this pathway as well. Arguably, enhancing preventive promotive factors in response to the two temperament types lessens the risks of developing the personality disorders associated with serious and violent offending.

Pathway D: Childhood Maltreatment

Image Description

This figure illustrates Pathway D: profile of victims of childhood maltreatment. To start, post-traumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, poverty and lack of family resources could lead to poor school performance and early drop-out. The cycle continues with the formation of young single-parent families in which researchers have found that harsh parenting practices undermine the parents' relationships with the children. These relationships can be characterized by chronic, violent or negligent maltreatment, which makes children more susceptible to CIC placements. Multiple CIC placements affect school performance during adolescence, which can be accompanied by substance abuse and early criminal behaviour, and end with involvement with the criminal justice system. In turn, these encounters with the criminal justice system lead to multiple CIC placements.

Exposure to early childhood abuse may impact the ability of the child to develop within healthy ranges. Further, the impacts of exposure to severe early maltreatment may continue to affect development through later childhood and adolescence, thereby impacting the likelihood of engaging in prosocial childhood, adolescent, and adult behaviours. Young offenders who have been exposed to early maltreatment are hypothesized to represent a distinct group of individuals facing unique developmental challenges that impair their ability to respond effectively to risk factors experienced later in life. This section will provide a brief overview of risk factors associated with early child maltreatment and outline the impact of exposure to this risk factor on subsequent development and antisocial tendencies.

Exposure to Early Childhood Maltreatment

Chronic traumatic stress in the early stages of development, such as exposure to severe maltreatment, may decrease the capacity of the brain to moderate aggressive and impulsive behaviours both in childhood and later in life. In particular, children who grow up in an atmosphere of unpredictable violence have been found to be more likely to become hyper-vigilant to perceptions of threats which increased impulsive and aggressive responses to circumstances typically not perceived as threatening or offensive (Perry, 1997). Similarly, maltreated children have been found to be more prone to tachycardia (abnormally fast heart rate) with heart rates up to ten beats per minute higher than non-abused children (Perry, 1994).

In addition to impacting neurological development and ability to respond to external stimuli, maltreatment has been associated with both negative internalizing (i.e., anxiety, suicidal thoughts, depression, withdrawal) and externalizing behaviours (Herrenkohl & Herrenkohl, 2007; McFarlane et al., 2003). Also, based on findings from Canadian research, it has been found that having experienced trauma in childhood places youth at an increased risk of substance abuse, especially hard drugs (Corrado & Cohen, 2002). The link between aggressive behaviours and sustained physical maltreatment is evident in the findings of a recent study involving more than 2700 families in the United States, in which researchers consistently found that children reported as aggressive by their parents were at an increased probability of suffering physical abuse (Berger, 2005).

Impact of Early Childhood Maltreatment on Behaviours

A strong relationship has been observed between single-parent homes and harsh parenting practices (Benzies, Keown, & Magill-Evans, 2009) and adolescents in single-parent households have been found to be significantly more likely to engage in antisocial behaviours (Demuth & Brown, 2004; Fergusson, Boden, & Horwood, 2007), thereby creating an increased likelihood of stacked risk factors for these youth. In particular, paternal absence in childhood has been identified as an important risk factor, since youth whose fathers were never present in the households were more likely to have engaged in various forms of delinquency and problem or risk-taking behaviour, including sexual promiscuity, crime, and substance abuse. For youth whose parents were once married, the timing of marital dissolution was relevant, because the likelihood of engaging in antisocial behaviour increased with the length of time the child lived absent of his/her father (Antecol & Bedard, 2007). In effect, in intact families, fathers were a protective factor against delinquency (Zimmerman, Salem, & Notaro, 2000) while paternal absence generally was associated with early school drop-out (Painter & Levine, 2000). This relationship has been explained in relation to prosocial parental routine involvement, monitoring, and closeness with their children (Demuth & Brown, 2004). With nearly one fifth of children in Canada in 2004 residing in single-parent homes, the impact of single-parenthood is of great interest (Vanier Institute of the Family, 2004).

Stress associated with single parenthood may inhibit appropriate parent-child attachments and bonding, and this may have serious implications for development. It was recently found that infant attachment status at one year of age was correlated with the development of conduct problems among children (Vando, Rhule-Louie, McMahon, & Spieker, 2008). Though this relationship was not mediated by hostile parenting or maternal depression, hostile parenting has been linked to conduct problems among insecurely attached children (Vando et al., 2008). It has been theorized that there is a cyclical relationship between attachment and conduct problems whereby conduct disorder developed early and untreated, first initiates a negative cycle where the child fails to learn to inhibit aggressive behaviour and to use socially appropriate means to resolve conflict (Tremblay et al., 2005). Second, the routine interactions between the parent and child involve mutually coercive patterns with limited problem resolution options (Patterson, 2002). Third, this initial conflict pattern intensifies the development of an insecure attachment, which, fourth, reduces the opportunities for normative development of, empathy, adaptive self-regulation, and other skills needed, ultimately, to inhibit antisocial outbursts including serious and violent offending in later developmental stages including adulthood (Hill, Fonagy, & Safier, 2003). This cycle of conflict may act to compound traumatic experiences associated with abuse.

As chronic maltreatment continues, these youth are at an increased risk of removal from the parental household. Given their likelihood to display conduct problems, these children are also likely to experience a high number of placement breakdowns. As discussed above, placement instability is a risk factor for antisocial behaviour (Newton et al., 2000). Much like children who have been exposed to prenatal risk factors, those who have experienced early maltreatment may experience difficulty in the classroom as a result of neurological impairments. However, these impairments are associated with physiological changes brought on by traumatic experiences among those in the latter category. For those raised in single-parent households characterized by chaos, with a parent who has limited time resources and weak attachments to the child, the likelihood of parental support overcoming challenges associated with school-work may diminish. As such, these children may be at an increased risk of displaying poor school performance. This likelihood may diminish further as the child is moved among various placements in the foster care system. The impact of poor school performance among these children is consistent with the challenges in the classroom faced by those who have experienced prenatal risk factors, and thus similar outcomes ensue.

Much like those who were exposed to prenatal risk factors, youth who were exposed to severe trauma are also likely to engage in early substance abuse. While part of this propensity is related to their stacked risk factors associated with poor school performance and inconsistent parenting, substance abuse among this group is best explained as an attempt of these youth to self-medicate to cope with the traumas they have experienced. Substance abuse, especially hard drugs, has been explained as a form of self-medication. In an incarcerated sample of serious and violent young offenders, substance abuse was very high and often associated with childhood trauma (Corrado & Cohen, 2002).

Recommended Intervention Strategy

This pathway poses several ethical challenges in developing intervention strategies. First, most families where major traumas are officially reported and official responses occur are low SES, single parent, and disproportionately from certain minority ethnic/racial groups (e.g., Aboriginal in Canada). Intervening in families with already fundamentally disadvantaged social-economic-political profiles to provide within family services for child trauma is sensitive because it increases the likelihood that both the victimizing family member will be charged criminally and those coercive interventions will occur including removing the child and care placements. The latter option is particularly concerning for the ethnic/racial integrity of the child when placements, especially longer term and adoption interventions, are selected. Second, the diagnostic tests, such as the functional magnetic resonance imaging techniques (fMRI), to ascertain the impact of serious trauma on the brain development of infants and toddlers are invasive, and utilize already scarce and costly medical resources. Third, it is difficult to provide effective within family interventions when the parent(s) are uncooperative, not uncommonly, because of their major mental health problems (paradoxically, for some parents, related to their childhood initiated PTSD). Fourth, in-care placement interventions for severe PTSD children and even adolescents require extensively resourced foster care families; education and training of foster parents as well as the foster family's biological children to provide a trusting and positive reinforcing environment for hyper-defensive and aggressive foster children. Without sufficient financial incentives and this education/training, the child is likely to experience further trauma resulting from the foster family perceived as having rejected the child by withdrawing their services. Again, multiple placements is a major risk factor for this pathway's cycle of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) causing externalizing behaviours that increase contact with youth justice, custody experiences, serious and violent offending, and then the continued reinforcement of PTSD into adulthood with this process is repeated.

Intervention strategies for this pathway focus first, and most challenging, on identifying families at high risk for child abuse. Instruments that assist in the identification of such families may be useful for service providers who have the most routine contact with them, such as public health nurses who visit all pregnant mothers in certain jurisdictions. Family doctors, walk-in-clinic doctors, emergency doctors and nurses, social workers, day care workers, and police are other potential sources of identifying the most egregious infant and toddler maltreatment cases while pre-school and kindergarten teachers can assist in the early childhood stage. The early identification of high risk families for child abuse is the first step in then providing the at-risk child with protection by assisting the family with daily resource supports that substantially reduce the likelihood of maltreatment. Where the risks remain too high despite such assistance then child care options outside the family are the next obvious and legally mandated intervention. Where major maltreatment has occurred then the latter interventions need to be followed by the complete diagnostic analysis that can identify any developmental problems, and very importantly, those associated with brain damage. There is considerable research that supports removing a major maltreated infant/child from victimizers as quickly as possible since even brain damage and severe trauma can be altered by secure and intensely loving care-givers. Neurologically, the infant brains are particularly characterized by “plasticity” where either the damaged areas heal or other parts are activated to allow for more normative functioning (Perry, 1997). Early childhood stage interventions also focus on providing major maltreated and traumatized children with secure, trusting and persistent adult relationships in contexts (e.g., day care, and school) other than just the home. This pattern is the essence of intervention programs through the remaining childhood and even initial adolescent stage. Most importantly, clinically-based and validated programs to treat PTSD are available. Again, the key to this pathway is to identify early trauma related to maltreatment to avoid further trauma by making the initial trauma the intervention priority.

Pathway E: Adolescent Onset

Image Description

This figure illustrates Pathway E: profile of adolescent onset young offenders. These youth are often associated with single-parent, low-income or high-conflict families, who furthermore usually live in socially disorganized neighbourhoods. In addition, criminal behaviour may be a risk factor that exists in the family. These children tend to do poorly in school and maintain relationships with antisocial peers who may encourage early substance abuse. All these factors may lead to antisocial behaviour and multiple CIC placements. Grappling with all these problems, these youth may find refuge in gangs and become involved with the criminal justice system. Researchers agree that the organizational structure of gangs is, in itself, a critical risk factor. Young people whose risk factors are cluster in adolescence may continue committing serious and violent offences into adulthood, most often in adult gangs, and become increasingly involved with the criminal justice system.

Though early risk factors are important in understanding serious and violent offending, many youth who engage in antisocial behaviour do not display antisocial tendencies in early childhood. These individuals are referred to as adolescent onset young offenders, and represent the largest proportion of young offenders. A brief discussion of adolescent onset offenders and related risk factors and outcomes will be discussed below.

Adolescent Onset

The dominant theory applied to explain these youth is that this developmental stage is the inherently difficult physical and emotional transition phase to young adulthood. Moffitt (1993), for example, asserted that most of the young offenders who begin offending in adolescence desist when they reach late adolescence and early adulthood where they become involved with mature relationships and become independent of parents and other authority figures. However, adolescent young offenders, nonetheless, are characterized by many of the risk factors for serious and violent offending and may experience many similar outcomes if their antisocial behaviours are not addressed quickly and effectively.

Impact of Adolescent Onset on Behaviours

Adolescent onset offenders typically reside in socially disorganized areas and have a family history of criminality. A recent American study found that high levels of physical neighbourhood disorder (e.g., presence of graffiti, liquor bottles and cigarette butts, broken glass, and abandoned cars) correlated with high levels of teenage pregnancy and increased levels of crime, injuries and homicides related to firearm use, regardless of measures of poverty and minority concentration (Wei, Hipwell, Pardini, Beyers, & Loeber, 2006). Also, concentrated economically disadvantaged Chicago neighbourhoods with low levels of collective efficacy (i.e., the willingness of neighbours to act collectively to monitor minor public deviances such as graffiti and prostitution) have been found to be highly predictive of elevated homicide rates (Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, 2001). In effect, there appears to be a strong neighbourhood interaction with both family dysfunction risk factors and related risk factors (Turner, Hartman, & Bishop, 2007). Other research has also found that as community disadvantage increased, so too did the relationship of family risk factors such as poor attachments, physical punishments, and coercive parenting, on higher levels of crime (Hay, Forston, Hollist, Altheimer, & Schaible, 2006).

These youth tend to do poorly in school, not as a result of a personality disorder or cognitive disability, but rather because they skip classes and reject authority out of boredom and the desire to act as adults. In the process of adopting adult-like behaviours, these individuals engage in substance abuse and routine minor antisocial behaviours. These behaviours are often the main reason youth in his pathway are placed in care. Additionally, they run away from home and/or are kicked out. Depending largely on neighbourhood factors (e.g., concentrated social-economic disadvantage and ethnic/racial homogeneity), family factors (e.g., family criminality and single parenthood, and poor school performance), individuals in this pathway are a major source of recruitment into informal and formal gangs (Howell & Egley, 2005; Thornberry, Lizotte, Krohn, Smith, & Porter, 2003b). Belonging to these antisocial and criminal groups result in their involvement in serious and violent offending and custodial sentences (Thornberry et al., 2003a; Gatti et al., 2005). It has been maintained that gang members are not that different in terms of risk factors from seriously antisocial individual youths and informal youth groups except that they have more of these risk factors (Howell & Egley, 2005). However, there is a consensus among researchers that organizational structure of formal gangs alone is a distinctively critical risk factor which explains both the uniquely high levels of serious and violent behaviours of gang members, and the extreme difficulties in devising and implementing effective interventions. In addition, gang structures vary enormously by country and within countries. In effect, there is a significant number of youth whose risk factors are concentrated in the adolescent stage, and who continue serious and violent offending into adulthood stages (Lacourse et al., 2003; Stouthamer-Loeber et al., 2008).

Recommended Intervention Strategy

Most interventions for this pathway involve traditional programs including education upgrading, trade skills training, cognitive-based therapies, independent living experiences, and apprenticeships. A major objective is to provide these youth with prosocial alternative lifestyle options. Again, a major theme of this pathway is that youth choose a criminal lifestyle which involves serious and violent offending because it provides them with a sense of belonging to a group, status, protection, income and excitement. Interventions, therefore, have to provide the opportunities for realistically obtainable lifestyles that meet, at least, most of these youthful imperatives.

Conclusion

This report addressed an important policy issue in youth crime prevention in Canada and in other jurisdictions. It focused on the question of why intervention programs that were designed to reduce the number of young offenders who engage in serious and violent offending have not been as effective. The answers are that: (1) there is a lack of sufficient understanding about why youth assault, commit robbery and murder; (2) research aimed at uncovering the “causes” rather than just the correlates of these behaviours is inadequate and/or lacking; (3) intervention programs that have been utilized appropriately or validly are too few; and (4) there is the need for new intervention strategies which reflect the most recent advances in identifying the theoretically and conceptually complex profiles of risk factors. The focus of this report is on the last answer.

One difficulty in answering the question of why intervention programs that were designed to reduce the number of young offenders who engage in serious and violent offending have not been as effective relates to the fact that many of the large older studies addressing why children and youth become involved in antisocial behaviours including crime do not have large subsamples of serious and violent offending. Instead child delinquencies and the far more prevalent and less serious youth property crimes have been the focus of theorizing and arguably interventions. However, in the last decade and a half, this has changed. The review of risk factors, both traditional and new, has been subject to extensive theoretical debates about why a small percentage of young offenders in various national jurisdictions commit serious and violent crimes. One key theme is that there are multiple pathways to offending and, therefore, there is a need to consider multiple intervention strategies. The five pathway-intervention strategies have many over-lapping or shared risk factors and interventions; however, there are fundamental differences in the timing of the interventions in terms of developmental stages and the primary “causal” risk factor to be addressed. Most encouragingly, it has been possible to begin incorporating specific programs to reduce the likelihood of individual or sets of related risk factors identified for each pathway. Cumulatively, the specific programs are hypothesized to reduce the likelihood of an individual embarking on a serious and violent offending pathway. Clearly, several of the diagnostic and service delivery programs have had only limited applications or utilization, and therefore, will have to undergo further validation before they can be incorporated into an integrated intervention strategy. This is especially important for those interventions that involve ethically, culturally, and politically sensitive issues. Nonetheless, it is hoped that this report intensifies the discussion and promotes the debate on how to reduce serious and violent offending in Canada and other jurisdictions.

Reference List

Agnew, R. 2008. Juvenile Delinquency: Causes and Control. (3rd ed.) New York: Oxford University Press.

Ainsworth, M. 1991. “Attachments and other affectional bonds across the life cycle”. In C.M. Parkes, J. Stevenson-Hinde, & P. Marris (Eds.), Attachment Across the Life Cycle (pp. 33-51). London: Tavistock Publications.

Ainsworth, M. 1969. “Object relations, dependency and attachment: A theoretical review of the infant-mother relationship”. Child Development, 40:969-1025.

Alltucker, K. W., M. Bullis, D. Close, & P. Yovanoff. 2006. “Different pathways to juvenile delinquency: Characteristics of early and late starters in a sample of previously incarcerated youth”. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15:475-488.