Trends in Indigenous Policing Models: An International Comparison

Executive summary

The report reviews Indigenous policing models in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. These countries were selected due to similarities in their colonial history, laws, political structures and the socio-economic outcomes of their respective Indigenous peoples. The purpose of the report is to facilitate opportunities for the exchange of information on Indigenous policing models, research and policy issues. The report, however, is not an exhaustive overview of all Indigenous policing initiatives, but an attempt to initiate information sharing, and enhance cross-national communication and discussion in this critically important area.

In the countries reviewed, the Indigenous population is growing at a more rapid rate than the non-Indigenous people. At the same time, the Indigenous people have a much higher rate of offences, arrest and incarceration than non-Indigenous population. Furthermore, the Indigenous people are more socially and economically challenged in terms of unemployment, education and health care.

This setting poses a challenge for delivering policing services. Among the countries reviewed, Canada is alone in having a comprehensive and national policing program (FNPP) for its Aboriginal peoples. In the United States many of the reservations have their own policing services which evolved from Congressional legislation. Recently, Congress passed the Tribal Law & Order Act of 2010 to help establish partnerships between the Tribes and Federal government to better address the public-safety challenges that confront the Tribal communities. In Australia, the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths and Custody was the impetus for determining how policing models will service the Indigenous communities. Recently, the policing models have also been associated with the development of community partnership agreements and performance measures to better determine the impact of policing services. In New Zealand, policing services models continue to follow the Māori Responsiveness Strategy, which is geared towards building partnership and relations with the Māori people.

The report identifies a few promising policing practices that can have a positive impact on public safety for Indigenous people. These practices where incorporated into an integrated policing model which highlights the importance of such factors as police training, the development of community partnerships, understanding Indigenous tradition and culture, and the use of a holistic framework. Finally, the report concludes that there is a critical need for further empirical research and more information sharing, and cross-national exchanges.

Introduction

This report provides an update to a document by Lithopoulos (2007) entitled, “International Comparison of Indigenous Policing Models,” which gave a brief review of current policing programs and initiatives relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand. These countries were selected due to similarities in their colonial history, laws, political structures and the socio-economic outcomes of their respective Indigenous peoples. The purpose of the report is to facilitate opportunities for the exchange of information on Indigenous policing models, research and policy issues. The report, therefore, is not an exhaustive overview of all Indigenous policing initiatives, but an attempt to initiate information sharing, and enhance cross-national communication and discussion in this critically important area.

This paper has been subdivided into five sections:

- The first section deals with Aboriginal policing in Canada, and the application of a national and comprehensive First Nations Policing Policy by the Canadian government, in partnership with provincial governments and First Nations communities;

- The second section analyzes the American tribal experience in the development of their own police services since the inception of tribal policing in the late 19th century, which were aimed at dealing with issues of lawlessness on newly created Indian reservations;

- The third section provides an overview of Indigenous auxiliary policing in the six Australian states and two territories. In addition, it provides a brief description of the Anunga Rules regarding police interrogation of Indigenous prisoners;

- The fourth section deals with the New Zealand Police's attempt to deal with Māori over-representation within the criminal-justice system, and their pioneering work in Restorative Justice Programs for Māori youth; and

- The final section provides a discussion of Indigenous policing initiatives in the four countries, as well as policy and research implications concerning the future of Indigenous policing, and the need to develop more opportunities for cross-national discussion in this area.

Throughout this report, the term “Indigenous” is used to describe the Aboriginal, North American Indian, First Nations, Inuit, Māori, and Torres Strait Islander populations of the four countries. The only exception is when discussing specific national programs and approaches that use specific terminology for a specific ethnic group.

Approach

The review of Indigenous policing models in Canada, the United States, Australia and New Zealand involved a few activities. First, scholarly and professional literature from 2007 to the present was reviewed.Footnote 1 This time-frame was expected to capture any new or innovative policing models in Indigenous communities since the report produced by Lithopoulos (2007). The focus was on policing or law-enforcement models viewed as innovative, promising or a best practice supported with evidence-based information. Second, data on policing expenditures, employment, and population information were further reviewed to identify any trends.

The literature review sought to identify evaluations of relevant policing models specifically focusing on Indigenous communities, published in scholarly journals, books, government reports, law-enforcement publications and annual reports. The search for relevant literature included scholarly databases (e.g., Criminal Justice Abstracts) and Internet searches, as well as the websites of law-enforcement agencies. E-mails were also sent to policing and government organizations to gather information or seek clarification.

The purpose of an international review of Indigenous policing models is to identify themes and issues of concern. This is an important benchmarking exercise to establish what is known. Attempts will also be made to identify best or promising practices in policing Indigenous communities.

There are, however, several caveats. These include: limitations on evidence-based information, the challenges of cross-cultural research and making international comparisons; different legal systems and structure; the historical and legal settings of Indigenous communities, and the limitations on cultural determinants of “within-country” differences, are inconsistent among the Indigenous communities (Pakes, 2010; Meyer, 1972). Despite these caveats, a comparison of Indigenous policing models is possible if caution is taken and the focus is on broader trends.

Section 1: First Nations policing in Canada

Overview

In Canada, there are 617 federally recognized “Indian” bands, also referred to as First Nations. To date, the Canadian First Nations have been awarded about 3.55 million acres of trust land (“reserves”) for their own use (AANDC, 2013).Footnote 2

Section 35 of the Constitution Act recognizes the “Rights of the Aboriginal (Indigenous) People of Canada,” and provides a definition of Aboriginal peoples of Canada. Pursuant to the Act, Aboriginal peoples of Canada include the “Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada” (Canada, 1982). Similarly, the Canadian census form mirrors the constitutional definition and uses the terms North American Indian, Métis, and Inuit, and allows each individual respondent to self-identify with their group.

According to the 2006 census, the term “North American Indian” refers to persons who consider themselves part of the First Nations of Canada, whether or not they are registered (that is, have legal Indian status) pursuant to the Indian Act with Aboriginal and Northern Development Canada (AANDC). “Métis” refers to people of mixed Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal ancestries who identify themselves as Métis. The Inuit are Aboriginal people who originally lived north of the tree line in Canada, and who self-identify as such (also sometimes referred to as “Eskimos”). Furthermore, in 2011 the National Household Survey asks if individuals are status Indians and if they are members of a band (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Demographics

The 2006 census also found that 1.2 million people in Canada identified themselves as “Aboriginal.” Canada's Aboriginal population is growing faster than the general population, increasing by 20.1 per cent from 2001 to 2006. This is due to a higher fertility rate among Aboriginal women than among other Canadian women, and legislative changes restoring status and membership rights to individuals previously excluded from being officially considered “Aboriginal.” Of the three Aboriginal groups (North American Indian, Métis, and Inuit), Métis had the largest population growth, with an increase of 33 per cent between 2001 and 2006 (Statistics Canada, 2008). In comparison, the non-Aboriginal population grew by only 5.44 per cent during same period.

Of the total number who claimed to be Aboriginal:

- 698,025 identified themselves as North American Indian;

- 389,780 as Métis and

- 50,480 as Inuit.

According to Statistics Canada, in 2006, the median age of the Aboriginal population was 27 years, 13 years lower than the median age of non-Aboriginals (40 years). Children and youth aged 24 and under made up 48 per cent of all Aboriginal people, compared with 31 per cent of the non-Aboriginal population. About 9 per cent of the Aboriginal population was aged 4 and under, nearly twice the proportion of 5 per cent of the non-Aboriginal population. Similarly, 10 per cent of the Aboriginal population was aged 5 to 9, compared with only 6 per cent of the non-Aboriginal population (Statistics Canada, 2008a).

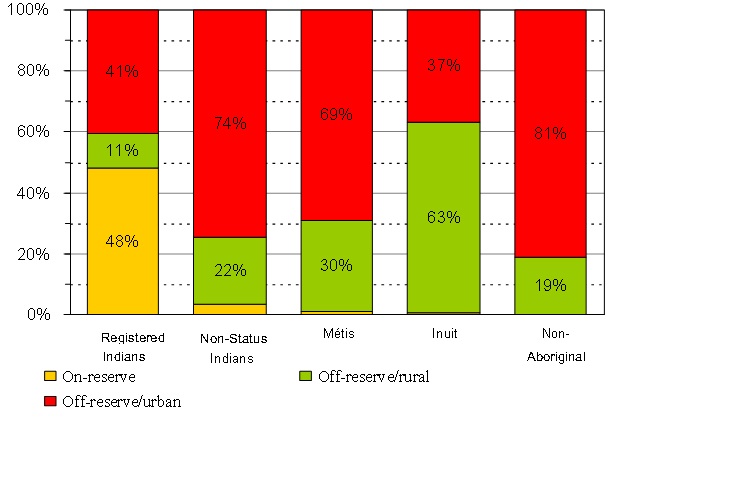

In 2006, more than 53 per cent of Aboriginal people resided in urban areas compared with 81 per cent for non-Aboriginals. One in 10 people who live in the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, are Aboriginal. Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the Aboriginal population by area of residence for 2006. The figure shows that in 2006, around 48 per cent of registered Indians lived on reserves. The majority of non-Status Indians (74 per cent) and Métis (69 per cent) lived in urban areas. Approximately 63 per cent of Inuit live predominantly in rural areas particularly in the North.

Figure 1: Aboriginal Population Distribution by Area of Residence in Canada, 2006

Image Description

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of the Aboriginal population by area of residence for 2006. The figure shows that in 2006, around 48 per cent of registered Indians lived on reserves. The majority of non-Status Indians (74 per cent) and Métis (69 per cent) lived in urban areas. Approximately 63 per cent of Inuit live predominantly in rural areas particularly in the North.

Social and economic statistics

In Canada, Aboriginal people are a major part of Canada’s population. While many Aboriginal people do well, on average the Aboriginal population suffers from higher unemployment, lower levels of education, below-average incomes and many other indicators of limited socio-economic and health conditions (Statistics Canada 2008a; Urban Aboriginal Economic Development, 2008; Wilson & Macdonald, 2010; Public Safety Canada, 2012).

Usalcas (2011) indicated that the recent downturn in the labour market that began in 2008 has had more of an impact on Aboriginal people than non-Aboriginal people. Among Aboriginal employable people, men fared worse than women during the 2008 to 2010 period. The unemployment rate among Aboriginal men increased to 13.3 per cent in 2010, up 4.1 per cent over the two-year period. Over the same time, the unemployment rate for Aboriginal women increased by 1.9 per cent to 11.3 per cent.

Another indicator of improved social conditions is post-secondary education. Milligan and Bougie (2009) pointed out that according to the 2006 census, 44 per cent of First Nations women aged 25 to 64 had completed some form of post-secondary education. Of these graduates, 21 per cent had obtained a college diploma. An additional 9 per cent had a university degree, 9 per cent had a trade or journeyperson certificate, and 5 per cent had a university certificate or diploma below the bachelor’s level.

Over the past decade, there are some positive economic indicators. Aboriginal people are participating in the market economy. Both labour-market participation and the unemployment rate are better today than several years ago (Usalcas, 2011, Statistics Canada, 2008). There has also been an increase in aboriginal entrepreneurs operating successful businesses across all industries (Burleton & Gulati, 2012). Burleton and Gulati noted that the number of aboriginal businesses will increase in the next several years, and that the majority should be profitable.

History of Aboriginal policing in Canada

Historically, the Canadian federal government – through the Dominion Police and later the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) – provided policing services on reserve, because of the prevailing view that the federal government was fully responsible for all aspects of Indian affairs and had sole jurisdiction for all Indian reserves (the federal- enclave theory). The federal-enclave theory began to give way in the 1960s and 1970s as a result of several studies, task-force reports and Supreme Court decisions that constitutionally sanctioned extensive provincial jurisdiction over Indians both on and off reserve (DIAND, 1990).

The RCMP began to withdraw from policing reserves in Ontario and Quebec as the federal role began to evolve from direct police-service delivery to financial support for on-reserve policing. In the mid-1960s, DIAND commissioned a study by the Canadian Correctional Association. The report, Indians and the Law, submitted in 1967, made numerous recommendations relating to the improvement of policing services provided to First Nations communities, including the expansion and improvement of the band- constable system. DIAND subsequently obtained Treasury Board approval to develop a more elaborate program, published as Circular 34 on April 28, 1969. The program resulted in an increase in the number of band constables from 61 in 1968 to 110 at the end of March 1971. The cost of this program was borne entirely by DIAND.

This program was further defined by means of Circular 55, issued September 24, 1971, which – among other things – stated that the objective of the program was to supplement senior police services at the local level, not supplant them. The jurisdiction of the band constables remained quite limited, as they received little or no training. Generally, band constables are not allowed to carry firearms, and are empowered to handle only band by-law enforcement and civil matters (Canadian Correctional Association, 1967).

In 1973, a second, more broad study, Report of the Task Force: Policing on Reserves, examined ways and means to improve policing services for First Nations communities. The Task Force focused on the Band Constable Program and the employment of Aboriginal people in a comprehensive policing role, and proposed the expansion and improvement of the Program (DIAND, 1973).

In connection with the development of fully empowered police officers, the 1973 Task Force examined three basic options, the first two of which were based on band council or municipal policing. Option 3(a) proposed the establishment of autonomous Aboriginal police services, while option 3(b) proposed the development of an Aboriginal special constable contingent within existing police services. The Task Force recommended that option 3(b) be made available to interested First Nations (DIAND, 1973).

In 1973, the federal Cabinet approved the Indian Special Constable Program and authorized the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development to enter into agreements with the provinces to share the cost (on a 60-per cent federal/40-per cent provincial ratio) of employing “Indian Special Constables” to provide on-reserve policing as part of provincial policing services (DIAND, 1973).Footnote 3A 1978 evaluation of the RCMP 3(b) program concluded that it was relatively successful in achieving its goals, and should be expanded rapidly to include more communities that were reporting a need for increased police services. In addition, the report indicated that community members felt that RCMP special constables were better trained and supervised than other police officers available on reserve at that time, that the attitude of regular RCMP members towards First Nations had improved and that they were developing better relationships with First Nations peoples (DIAND, 1983).

In June 1991, after extensive consultation with the provinces, territories and First Nations across Canada, the federal government announced a new on-reserve First Nations Policing Policy (FNPP). Following a joint recommendation by the Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development and the Solicitor General of Canada, the First Nations Policing Program was transferred to the Department of the Solicitor General of Canada in 1992, to take advantage of the department’s policing expertise.Footnote 4 The Aboriginal Policing Directorate (APD) was created and given responsibility for the implementation, maintenance and development of the First Nations Policing Program within the framework of the FNPP.

The program was successfully implemented across Canada through tripartite agreements negotiated between the federal government, provincial or territorial governments and First Nations, to provide police services that are effective, professional and tailored to meet the needs of each community. Tripartite agreements stipulate that the federal government pays 52 per cent and the provincial or territorial government 48 per cent of the cost of First Nations policing services.

Aboriginal policing agreements in Canada

A First Nations self-administered policing agreement is an arrangement between Canada, the participating province or territory, and the First Nations community. In these arrangements, the First Nation develops, manages and administers its own police service under provincial legislation. Independent police commissions provide for the impartial and independent oversight of police operations, and the police chief is responsible for the management and administration of the service.

Demand for First Nations police services has grown exponentially over the years. As of February 22, 2013, about 528 First Nations communities out of the eligible 617 are covered under the FNPP. This represents about 80 per cent (503,365) of the eligible on-reserve First Nations population. Among the 528 communities, federal and provincial governments fund 163 tripartite policing agreements throughout Canada. This includes 33 First Nations self-administered policing agreements, 113 Royal Canadian Mounted Police community tripartite agreements (RCMP CTAs), three RCMP First Nations community police service framework agreements and three municipal-type agreements, where policing services are provided to the First Nations communities. Table 1 provides an overview of these agreements.

The RCMP CTAs are negotiated between the federal government, the participating province or territory and the First Nations community. To this end, the First Nation is policed by its own dedicated contingent of Aboriginal RCMP officers. In addition, community advisory bodies are established to act as the conduits between the community and the RCMP.

Framework agreements are bilateral agreements signed by Canada and participating provinces or territories. They provide the administrative and financial framework for individual RCMP CTAs, and must be in place prior to the negotiation of CTA agreements.

In addition, prior to the inception of the First Nations Policing Program in 1992, there were two legacy programs. First, the RCMP Aboriginal Community Constable Program (ACCP) which began in 1977, though some form of this program that started in the 1960s (Alderson-Gill, 2006). The ACCP program is cost-shared at 46 per cent by the federal government and 54 per cent by the provincial or territorial government. There are now 55 ACCPs. Second, is the Band Constable Program (BCP), where Band Constables are responsible for enforcing band by-laws. They also refer to the RCMP or provincial police cases involving the Criminal Code or offences under other federal or provincial legislation. The BCP agreements are funded at 100 per cent by the federal government. These are bilateral agreements between a First Nation and the federal government (Evaluation Directorate, 2010). There are 45 BCPs. Tables 1 and 2 give an overview of these two programs.

Expenditures

For the 2011/12 fiscal year, the federal and provincial/territorial governments’ total contribution to First Nations policing was $233 million. The federal government provided $122 million and the provincial/territorial governments allocated $111 million. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the FNPP expenditures. On March 4, 2013, the federal government announced that it will maintain funding for the FNPP for the next five years.

| Agreement Types | Federal Gov’t Contributions | Provincial/Territorial Gov’t Estimate | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Nation Policing Program | $114,466,743 | $105,661,609 | $220,128,352 |

| Pre-FNPP (Legacy) programs | $7,117,531 | $5,465,463 | $12,582,994 |

| Total | $121,584,274 | $111,127,072 | $232,711,346 |

Source: Public Safety Canada (2012)

Police officers employed

Table 2 gives an overview of the number of Aboriginal police officers funded under the FNPP. In total, 1,452 individuals are employed as police officers. Among this number:

- 840 officers work for First Nations self-administered police services

- 64 officers work under the RCMP Community Police Service Framework Agreements

- 10.5 officers work under municipal-type agreements

- 77 officers are employed under the Aboriginal Community Constable Program

- 120 officers work under the Band Constable Program

- 346 officers for RCMP CTAs

- 32 officers for the RCMP Provincial Framework Agreements

| First Nations Policing Program | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types of Agreements/Program | Number of Agreement | Communities Served | Total Populations | Number of Officers |

| First Nations Self-Administered Policing | 38 | 176 | 168,922 | 840 |

| Community Tripartite | 113 | 191 | 149,730 | 340 |

| Municipal Type | 3 | 3 | 1,854 | 10.5 |

| Total | 161 | 396 | 338,110 | 1,254.5 |

Pre-First Nations Policing Program Arrangements (Legacy Programs) |

||||

| Number of Detachments | Communities Served | Total Populations | Number of Officers | |

| Aboriginal Community Constable Program | 55 | 87 | 100,387 | 77 |

| Band Constable Program | n/a | 45 | 64,868 | 120 |

Source: Public Safety Canada (2012)

Aboriginal crime statistics

According to the Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (Brzozowski et al., 2006), Aboriginal peoples have the highest rates of actual offences, arrest and incarceration of any group in Canada. In 2010, when the incidence of crime in communities with FNPP police services was compared to the rest of Canada, the following rates were identified:

- Crimes are 3.8 times higher

- Violent crimes are 5.8 times higher

- Assaults are 7 times higher

- Sexual assaults are 5.4 times higher

- Drug trafficking are 3.8 times higher (Public Safety Canada, 2012)

However, from 2004 to 2011, communities with FNPP-funded self-administered (SA) police services have experienced a decrease in criminality. Public Safety Canada (2012), as part of the FNPP performance analysis, reported the following:

- 22% decrease in incidents of crime

- 36% decrease in homicides (Whereas Canada witnessed a 16% decrease in the number of homicides)

- 19% decrease in violent criminal incidents

- 20% decrease in assault

- 23% decrease in sexual assaults

Crime severity index

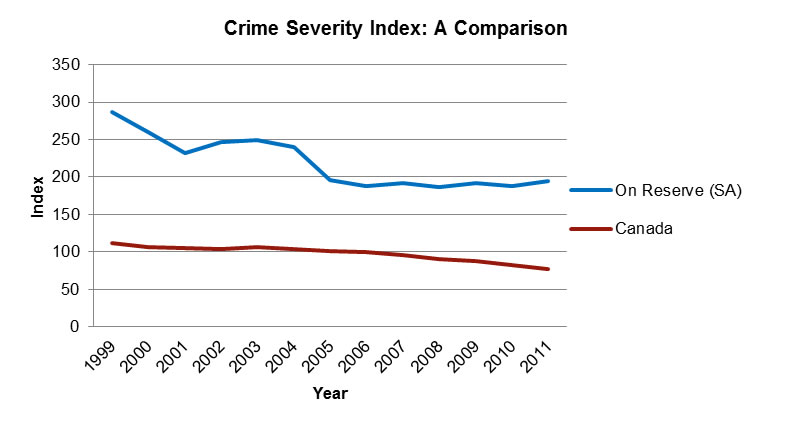

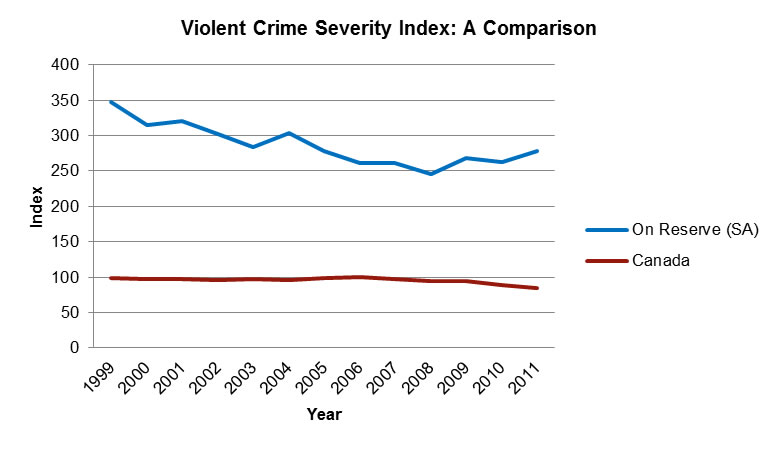

The Crime Severity Index tracks changes in the severity of police-reported crime by accounting for both the amount of crime reported by police in a given jurisdiction and the relative seriousness of these crimes (Statistics Canada, 2009).Footnote 5 The indices for Crime Severity (Figure 2) and Violent Crime (Figure 3) for First Nations communities were compared to those in the rest of Canada.

Figure 2 shows that crime severity has decreased 91.8 points from 1999 to 2011 for communities policed under the self-administered policing model. By comparison, crime severity in Canada declined by only 33.6 points during the same period. Figure 3 illustrates that for the years 1999 to 2011, violent crime severity has fallen 70.4 points for First Nations communities policed under the self-administered policing model. During the same period, violent crime severity has decreased only 14.1 points.

Figure 2: Comparison of Crime Severity Index Between on Reserve and Canada for the years 1999-2011

Image Description

Figure 2 shows that crime severity has decreased 91.8 points from 1999 to 2011 for communities policed under the self-administered policing model. By comparison, crime severity in Canada declined by only 33.6 points during the same period.

Figure 3: Comparison of Violent Crime Severity Index between on Reserve and Canada for the years 1999-2011

Image Description

Figure 3 illustrates that for the years 1999 to 2011, violent crime severity has fallen 70.4 points for First Nations communities policed under the self-administered policing model. During the same period, violent crime severity has decreased only 14.1 points.

Evaluation of Canadian Aboriginal policing programs

Inherent in the inception of the FNPP by the Canadian government was the idea that Aboriginal officers and services would be more effective in policing the on-reserve population than non-Aboriginal police officers and services. This was going to be achieved through the establishment of policing agreements. Also inherent in the program was the commitment to evaluation to see whether the program met its objectives and to what extent; and, if it did not, to determine why the goals had not been achieved.

In 1995, an evaluation of the FNPP produced ambiguous results primarily because the methodology relied too heavily on anecdotal information sources. The evaluation concluded that evidence from case studies suggested that Aboriginal communities were either more satisfied with the services provided under the program than they were with the previous arrangements, or they saw no change (Jamieson, Beals, Lalonde & Associates, 1995).

Several attempts have been made at the local level to assess satisfaction with police services in Aboriginal communities. The results of these surveys suggest large variation in the ratings of policing services by Aboriginal peoples. Two surveys in Quebec and Six Nations suggest levels of satisfaction with policing that more closely mirror those of the Canadian population at large. In the Quebec survey, 71 per cent of the on-reserve respondents indicated that the police were doing a very “satisfactory/very effective job” and 83 per cent in the Six Nations survey (Quebec, 2003; Six Nations, 2003).

In 2005, the Government of Canada participated in a syndicated research study of First Nations living on reserve to explore the state of affairs on reserves. The objective was to obtain the point of view of the residents themselves and to find out what issues were important to this unique segment of the Canadian population and what kinds of programs they felt they needed. This study involved two telephone surveys of about 4,000 First Nations residents living on reserve. Following the surveys, a series of eight focus groups were conducted throughout Canada. Half of these groups were conducted with youth, while the other half was conducted with adults (25 and over) (Ekos, 2005).

The results of these surveys show that, on the positive front, respondents did indicate that FNPP policing provided better response times and community coverage than non-FNPP policing (such as provincial policing services). In general, First Nations peoples in Atlantic Canada and the province of Quebec rated the performance of FNPP police services higher than those in the western provinces and Ontario.

In 2009, Public Safety Canada (2010) conducted a comprehensive review of the FNPP. The purposes of the review were to examine key elements of the program including service delivery models and funding mechanisms, and to suggest revisions to the policy framework. The reviewers were also to make recommendations regarding the sustainability, relevance and effectiveness of the FNPP (Public Safety Canada, 2010). The authors of the report found a continued need in First Nations and Inuit communities for police services that are professional, effective, culturally appropriate and accountable to the communities. However, cultural appropriateness and accountability can be achieved by strengthening the governance of the police service and adopting policing models that engage the communities to address the crime issues. The authors of the review further noted that “communities should be encouraged to engage in regular dialogue with local police services and provide the police with information about their culture, local community dynamics, and Indigenous approaches to justice and problem solving. Communities should also be supported to strengthen their Community Consultative Groups and Police Management Boards' abilities to oversee the performance of their police services against the objectives of the FNPP (Public Safety Canada, 2010:iii). ”

Section 2: American tribal policing

Demographics

In the United States, there are 561 federally recognized tribes (sometimes referred to as “nations”). Of these tribes, about 100 are located in the lower 48 states and have substantial land holdings, mostly in the form of reservations, but also off-reservation interests. About half of all tribes live in Alaska, in the form of villages. It is important to note that a few reservations are larger than certain states, while some are the size of large counties, and others are like cities and towns (BIA, 2002). The technical term for reserve land is “Indian Country,” which comprises approximately 56 million acres, with the majority located west of the Mississippi River.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2011), in April 2010, the total self-identified American Indian or Alaska Native population accounted for 5.2 million, or 1.7 per cent, of the estimated 308.7 million people in the United States. There were also 334 federally and state-recognized American Indian reservations. There are 4.6 million people living on American Indian reservations and 243,000 people living within Alaska Native villages.

Crime trends

The National Institute of Justice (2013) studies suggest that crime rates are much higher for Native Americans, compared with the national average. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, American Indians and Alaska Natives experience violent crimes at rates far greater than the general population.

A report by Perry (2012) for the U.S. Department of Justice on Tribal Crime Data Collection Activities found that the number of Indian country suspects investigated by U.S. attorneys for violence declined 3 per cent, from 1,525 in 2000 to 1,479 in 2010, while the number of Indian country suspects investigated for property, drug, and other offenses increased 57 per cent from 475 in 2000 to 746 in 2010. Perry noted that there is more violence per capita on tribal land than on non-tribal land in the United States. Perry further stated that in 2010, 4.8 million people lived on reservations or in Alaska Native villages and only 1.1 million of those residents – 0.4 per cent of the U.S. population –classified themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native. Yet, the 1,479 suspects investigated for violent offences in Indian country represented 23 per cent of all federal investigations for violent offences in fiscal year 2010.

Furthermore, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reported in 2011 that the Navajo Nation (Arizona) had the highest reported offences, followed by Seminole Tribal (Florida), Gila River Indian Community (Arizona) and Cherokee Tribal (North Carolina) (See Table 3). Table 3 also gives an overview on the defendants in criminal cases and those taking place in Indian Country. Among the 3,493 defendants charged with violent offense, 727 Indian country defendants made up 21 per cent of the total. The data further shows that 63.1 per cent of all defendants charged in U.S. district courts for crimes in Indian country were charged with violent crimes, compared to 3.4 per cent nationally (Perry, 2012).

In 2010, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that American Indians and Alaska Natives had the highest rate of violent victimization by strangers among all racial and ethnic groups in each time period: 1993-1998, 1999-2004 and 2005-2010 (Harrell, 2012) In an earlier study on family violence, Durose et al., (2005) found that when compared to other ethnic groups, American Indian/Alaska Natives showed the highest arrest rates for violent crime. More than half (55.2 per cent) of all suspected offenders of this group were arrested. Another study by the Centre of Disease Control (2008) reported that 39 per cent of Native women surveyed identified as victims of intimate-partner violence in their lifetime, a rate higher than any other ethnicity surveyed. Similarly, Malcoe and Duran (2004) in their study on low-income Native American women found 82.7 per cent of women had experienced physical or intimate-partner violence in their lifetime, 66.6 per cent reported severe physical partner violence and 25.1 per cent reported severe sexual partner violence.

Legal status of American tribes

The U.S. Constitution recognizes three levels of government: federal, state and tribal. There are consistent patterns and hard rules concerning the jurisdictional authority of all federally recognized tribes. These are reflected in federal policies, treaties, statutes, executive orders and case law. The U.S. government's relationship with federally recognized tribes is one of “government to government.” As such, American tribes have extensive experience in the internal management of their political affairs, as they have been empowered to develop their own institutions, constitutions, law codes, tribal courts, police services, correctional facilities, and to enact civil laws to regulate conduct and commerce.

As of 2000, the U.S. federal government's relationship with the tribes is one of “government to government” as required by Executive Order 13175 (U.S., 2000). Each federal agency has a duty to establish a consultative relationship with the tribes on matters that have substantial direct effects on one or more tribes, on the relationship between the United States and tribes, or on the distribution of power and responsibilities between the United States and the American tribes. In addition, federal courts have an expectation that consultations will be evident in matters that affect the tribes.Footnote 6

The government-to-government relationship between the U.S. government and the American tribes is not new. More than 500 years of history concern the Native peoples of North America and their relationship with non-Natives. The relationship began as a political and military reality in the 18th century with the signing of treaties between sovereign nations. In the 19th century, the relationship was strained as the United States varied its approaches from co-existence to subjugation to assimilation. In the 20th century, the relationship went from reorganization to termination to de facto federal control, and more recently to federal support for self-determination and self-governance.

History of tribal policing

In 1824, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) was established within the War Department to deal with American Indian affairs. The U.S. Army was tasked to police reservations with the overall policy aim of subjugating and assimilating the “Indians,” and to make sure they remained in their newly created reservations (Barker, 1998).Footnote 7 Crime-related problems on reservations—due a breakdown of traditional social controls—and the harsh treatment of American Indians by often-intoxicated Army personnel tended to create chaos, unrest, and a general state of lawlessness on tribal land. In the late 1860s, several BIA Indian agents developed local BIA police services at their own initiative to deal with the general state of lawlessness on reservations (Young, 1969). Organizationally, the peace officers were Indigenous persons under non-Indigenous management. The first BIA-organized Indian tribal police service was established on the Apache reservation in 1868; this service, incidentally, was instrumental in apprehending the famous Apache Chief, Geronimo (BIA, 1975).In 1883, the U.S. Congress officially recognized the importance of this program by authorizing funding for 1,000 privates and 100 officers. Organizationally, this was followed up in 1907 by the wholesale adoption of the professional policing model with the creation of a specialized criminal investigation branch, service training for BIA police officers, and the development of a central headquarters in Washington, D.C. This was the high-water mark in funding of BIA tribal policing. By the 1920s, tribal policing was severely hampered by a lack of resources for effective police services. For example, most reservations had one or two officers responsible for patrolling vast tracts of land (BIA, 1975).

From the late 1960s and early 1970s, due to increased Indian activism and militancy (for example, Wounded Knee), the Civil Rights movement, and positive changes in social attitudes towards minority rights, U.S. government policy towards its Indigenous peoples shifted from de facto control to one of support for tribal self-determination and self-governance. Government funding for tribal policing was increased, which provided for the development of the Indian Police Academy in Artesia, New Mexico (BIA, 1975).

In 1975, on the legislative front, the U.S. Congress enacted Public Law 93-638 (P.L. 93-638), the Indian Self-Determination Act and Education Assistance Act. Under this legislation, the American tribes acquired significant control over legislative authority, law enforcement and courts, education, taxation, economic development and environmental policy. P.L. 93-638 allows tribes to contract with the federal government to deliver their own services that were offered by the BIA and other agencies, including contracting todeliver their own police services. This was followed-up in 1994 by the Congressional enactment of the Indian Self-Determination Act. Under this Act, the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to grant funds to tribes for the express purpose of strengthening tribal government, including the provision of policing services; it is up to each tribe to determine the exact nature of policing required (Lunna, 1998).Organization, management and jurisdiction

In Indian Country, three forms of law-enforcement agency operate within Indian Country. These include:

- BIA Law Enforcement Services, where no police services are established by the tribes. This was accomplished with the introduction of the Indian law Enforcement Reform Act (PL 101-379) which established a division of law- enforcement services within the BIA to administer law-enforcement services in Indian country. The staff in these departments are federal employees with little or no accountability to tribal governments or the people they police. The long-term trend is to decrease the number of BIA agencies as tribes begin to assume control of the law-enforcement function in their territories. Currently, the BIA operates 42 police investigative programs (Reaves, 2008).

- Tribal Police, where police officers are funded through the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975 and the Indian Self-Governance Act of 1994. Also known as Public Law 93-638 (PL 93-638 or PL 638). This law gives tribes the opportunity to establish their own government functions by contracting with the BIA. Typically, a 638 contract establishes the department's performance standards and organizational framework and provides basic funding for the police services. In addition, full tribal control over law enforcement on tribal lands exists when a tribe assumes the total funding of its own police department. Currently, there are about 157 general purpose tribal police departments, and 21 special jurisdiction agencies whose primary role is to enforce natural resources laws pertaining to hunting and fishing on tribal lands (Reaves, 2008). The officers and civilian staff of tribal police departments are tribal employees (Wakeling et al., 2000).

- Local non-Indian police, where the tribal reservation is located within a political jurisdiction. This model is found almost entirely in those states where federal legal authority over Indian tribes was ceded to the state as a result of Public Law 83- 280, 67 Stat. 588 (1953). Congress gave six states (Alaska, California, Nebraska, Minnesota, Oregon, and Wisconsin), in which the transfer of jurisdiction was total and unconditional, and 10 “optional” states (Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Iowa, Montana, Nevada, North Dakota, Utah, and Washington), in which the jurisdiction transfer was done later, at those states' request (and was more selective and conditional in its coverage), for civil and criminal jurisdiction with respect to local tribes. This law, passed as part of a larger effort to “terminate” American Indian tribes, gave a number of states the power to enforce the same criminal laws within Indian Country as they did outside of Indian Country (Wells & Falcone, 2008; Goldberg & Singleton, 2008). PL 280 drastically altered criminal justice in American Indian and Alaska Native communities. The National Institute of Justice (2008) noted that prior to PL 280, criminal jurisdiction was shared between federal and tribal governments, with little interference from state governments. Tribal consent was not required and tribes were not consulted (Dimitrova-Grajzi et al., 2012; Goldberg & Singleton, 2008).

Jurisdictional confusion is also a major law enforcement problem on tribal land (Lithopoulos, 2007). Many enforcement problems arise, in part, from this confusion. For instance, many reservations are geographically remote and involve enormous tracts of sometimes non-contiguous land. Tribal officers must comply with traffic laws, restrictions on vehicle markings and other laws while off reservation (Hill, 2009). Thus, tribal officers must cover their emergency light bars and comply with speed limits when traveling on non-reservation lands, even if in pursuit of a suspect, or when responding to an emergency on a part of the reservation that requires the use of non-reservation roads (Giokas, 1992).

The power of tribal officers over non-Natives on reservation lands has been described as essentially a citizen's powers of arrest. Tribal officers may detain, but not arrest, non- Natives on reservations, and they may not pursue non-Natives off-reservation. They also must turn them over to state or local authorities as soon as possible, as there are time limits that tribal officers may detain non-Natives. If local authorities do not arrive in time, tribal officials must release the suspect or else face a lawsuit for false imprisonment (Giokas, 1992).

Initiatives have taken place to try to rectify the jurisdictional issues between tribal and state governments through cross-deputization agreements that allow tribal officers to enforce state law and local enforcement officials to enforce tribal law under specific conditions. In addition, there is statutory deputization, which allows states to authorize the deputization of qualified tribal officers as state peace officers; this is very similar to the Canadian model where provinces swear Aboriginal police officers as provincial peace officers (Lunna, 1998).

Congress passed the Tribal Law & Order Act of 2010 to help address crime in tribal communities, and emphasize the need to decrease violence against American Indian and Alaska Native women. The Act encourages the hiring of more law-enforcement officers for Indian lands and provides additional tools to address critical public-safety needs. Specifically, the law enhances tribal authority to prosecute and punish criminals; expands efforts to recruit, train and keep BIA and tribal police officers; and provides BIA and tribal police officers with greater access to criminal information-sharing databases (e.g., FBI's National Crime Information Center). The Act further authorizes new guidelines for handling sexual assault and domestic violence crimes, from training for law-enforcement and court officers, to boosting conviction rates through better evidence collection, to providing better and more comprehensive services to victims. The Act also encourages development of more effective prevention programs to combat alcohol and drug abuse among at-risk youth (U.S. Department of Justice, 2010).

The Tribal Law & Order Act of 2010 further encourages cross-deputization.Footnote 8 Tribal and state law- enforcement agencies in Indian country receive incentives through grants and technical assistance to enter into cooperative law-enforcement agreements to address crime in tribal areas. At the federal level, the Act enhances existing law to grant deputization to expand the authority of existing officers in Indian country, to enforce federal laws normally outside their jurisdiction, regardless of the perpetrator’s identity.

The Act also created the Indian Law and Order Commission. The Commission is an independent, volunteer advisory group that helps address the challenges of securing equal justice for Native Americans living and working on tribal lands. However, while the Act attempts to provide additional resources to law enforcement (and prosecutions), many authors have questions the overall intent, especially when budgets and resources for justice were reduced (Owens, 2012; Williams, 2012; National Congress of American Indians, n.d).

Indian-Country policing expenditures

In terms of the costs of delivering policing services, the U.S. Department of Justice, noted that collectively, general purpose tribal police departments provide policing services to about 1.2 million residents or 2.3 full-time sworn officers per 1,000 residents. These statistics do not include non-Indians living on tribal lands. In 2008, the per capita cost for tribal policing was about $257. In 2007, the U.S. average per capita cost for all local police departments was $260 (Bureau of Indian Affairs, 2013).

Table 4 below presents the BIA costs for law enforcement for the years 2011 to 2013. In 2011, the actual cost for law enforcement was around $537 million. In 2013, the budget requested for law enforcement was approximately $571 million, an increase of 7 per cent. However, funding has often been characterized as inadequate for effective policing in tribal communities. Wells and Falcone (2008) argued that American Indian reservations remain among the most chronically under-policed communities in the United States, despite their higher crime levels and alarming rates of victimization.

| Program Element | Law Enforcement (Dollars in thousands) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 Actual | 2012 Enacted | 2013 Budget Request | |

| Law Enforcement | 305,893 | 321,944 | 328,444 |

| Criminal Investigation and Police Services | 185,315 | 185,018 | 189,662 |

| Inspection/Internal Affairs | 3,194 | 3,100 | 2,941 |

| Law Enforcement Special Initiatives | 17,752 | 17,400 | 16,694 |

| Indian Police Academy | 5,133 | 5,073 | 4,956 |

| Tribal Justice Support | 3,288 | 5,641 | 5,518 |

| Law Enforcement Program Management | 10,476 | 10,145 | 8,700 |

| Facilities Operation & Management | 6,243 | 13,757 | 13,775 |

| Total | 537,294 | 562,078 | 570,690 |

Source: Bureau of Indian Affairs. FY 2013 Budget Request

Staff and personnel

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, in 2008, American Indian tribes operated 178 law-enforcement agencies which included 157 general-purpose tribal police departments and 21 special jurisdiction agencies, responsible for enforcing natural resources laws (e.g., fishing and hunting on tribal lands) (Reaves, 2011). In addition, the BIA (Office of Justice Services, Division of Law Enforcement) operated 42 agencies that provided law-enforcement services in Indian country to those Indian tribes and reservations that do not have their own police force. These law-enforcement services employed about 3,300 sworn police officers (Table 5).

| Type of Agency | Number of Full Time Employees | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Agencies | Total | Sworn | Civilian | |

| General Purpose Police Departments | 157 | 4,294 | 2,835 | 1,459 |

| Special resources agencies | 21 | 271 | 164 | 107 |

| BIA | 42 | 277 | 277 | unknown |

| Total | 220 | 4,842 | 3,276 | 1,566 |

Source: Reaves, (2011)

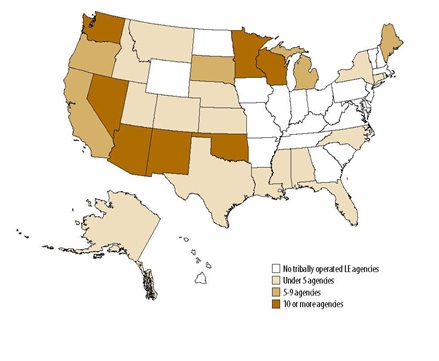

Figure 4 below shows the number of tribe-operated law-enforcement agencies in 28 states. Washington has 24 law-enforcement agencies, Arizona 22, Oklahoma 19 and New Mexico 17 had the largest number of tribal law-enforcement agencies. The largest Indian policing agency is the Navajo Police Department, which employed 393 full-time officers (2.0 sworn officers per 1,000 residents) to serve tribal lands in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah.

Figure 4: Location of Tribally Operated Law Enforcement Agencies, 2008

Image Description

Figure 4 shows the number of tribe-operated law-enforcement agencies in 28 states. Washington has 24 law-enforcement agencies, Arizona 22, Oklahoma 19 and New Mexico 17 had the largest number of tribal law-enforcement agencies. The largest Indian policing agency is the Navajo Police Department, which employed 393 full-time officers (2.0 sworn officers per 1,000 residents) to serve tribal lands in Arizona, New Mexico and Utah.

Summary of American tribal policing

A review of the research and policy literature on tribal policing reveals that little has been accomplished over the past several years. Since 2000, the main work was completed by Wakeling et al., (2001) which provided an overview on law-enforcement activities in Indian country. Goldberg and Singleton (2008) examined the effectiveness of law- enforcement and criminal-justice systems under Public Law 280. More recently, there is the Department of Justice report on the Compendium of Tribal Crime Data (2011), as well as a collection of the key reports and testimonies on Indian Country Criminal Justice, with few references to tribal policing (Indian Law and Order Commission, 2011).

A comparison was made between rural or Indian-Country with urban settings. Wells and Falcone (2008) pointed out that the development of law-enforcement models in Indian Country must be viewed in the context of rural rather than urban settings. In urban settings, good policing means making police response times as short as possible, and achieving preventive patrol with dense coverage of areas by numerous police officers in vehicles. In rural settings and in particular Indian Country, response times may be measured in hours or days, and preventive patrols are nonexistent, as only a few officers are available to cover hundreds of square miles. They argued that conventional ideas about optimal police patrol practices become almost unthinkable, making it even more of a challenge to develop useful models for policing Indian communities (2008:220). The authors concluded that the “ability to identify and implement more effective policies that will support and enhance Indian tribal policing agencies in the U.S. is stuck in limbo, awaiting better information about what various contemporary tribal policing practices are, in which communities these are used, and how they seem to work. Absent this information, the idea of “best practices” will remain an exercise in wishful speculation (2008:222).”

Wells and Falcone (2008a), in their review of tribal policing on Indian reservations, noted that research is scarce. While several reports and articles have provided excellent groundwork for understanding tribal law-enforcement activities, the authors noted that “despite social conditions in American Indian communities that are widely regarded as a national crisis, we find a dearth of systematic evidence-based information about how Native American communities are policed and how these compare with policing elsewhere in the USA (2008a:651).”

Section 3: Indigenous policing in Australia

Overview

In Australia, there are two ethnically and culturally distinct groups of Indigenous peoples, each with a different history and culture: the Aboriginal peoples and the Torres Strait Islanders. It is difficult to know how many Indigenous people lived in Australia before the inception of colonization in 1788, but it is speculated that there could have been from 750,000 to 1 million Australian Indigenous peoples – not “one country,” but up to 300 Indigenous nations, speaking approximately 250 languages and many more dialects (Samuelson, 1993).

The basis for the European takeover of the continent was the doctrine of terra nullius (land belonging to no-one). This meant that Indigenous lands were Crown lands in the eyes of British law. The premise that Australia belonged to no one was not because the British did not see Indigenous people living on the lands, but because Indigenous peoples did not seem to cultivate land or build permanent dwellings, as Europeans did (Samuelson, 1993).

Terra nullius meant that the land had no sovereign owner, and on this basis, Britain took possession of Australia without a treaty. There was also a prevailing (European) belief that colonization was in itself a “peaceful settlement.” Effectively, Indigenous peoples became trespassers on their own lands. In 1992, this concept was eventually overturned in a landmark decision by the Australian High Court concerning the Mabo Case, which recognized Indigenous title to land as part of the common law (Samuelson, 1993).

As in the other three countries analyzed in this report, Australian statistics document the fact that Indigenous peoples are overrepresented in the criminal-justice system. In addition, there has been a common element of institutionalized racism since colonization, and the historical role of the police as agents of colonization. As well, there is a common element of poverty, alcohol and alienation.

In Australia, as in the other three countries, explicit government policy generally assumed Indigenous people would eventually assimilate. For example, the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act, 1897, recognized that the population of Indigenous people was diminishing and moved them (sometimes forcibly) on to reserves. Consequently, the Australian Indigenous population dropped from as many as 1 million before 1788, to approximately 81,000 by 1933 (Samuelson, 1993). However, the 2001 census revealed that the Indigenous population has rebounded and there are currently about 410,000 individuals identified as Indigenous. This represents about 2.2 per cent of the total Australian population (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2002). According to Samuelson (1993) and Ross (1999), the following are the historical highlights of Indigenous peoples' legal status from the time Australia became an independent dominion to the present:

- 1901: The colonies federated as the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Indigenous people were written out of the constitution.

- They were not counted in the consensus and federal parliament did not have power to make laws for them.

- Indigenous people did not have the right to vote in federal elections until 1962.

- 1967 Referendum: Indigenous Australians gained full citizenship rights and started being counted in the national census (it also gave the federal government power to legislate Aboriginal affairs).

- Prior to 1967, the Australian Constitution was interpreted quite narrowly, so that “Aboriginal” was taken to mean persons with more than 50 per cent Aboriginal “blood.”

- 1972: the abolition of the White Australia Policy.

- Until 1972, the Indigenous peoples of Australia were excluded from voting, the public service, the armed forces and pensions.

Demographics

According to the 2011 census, there were 21.5 million people, of which Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders made up 2.5 per cent (about 500,000 people) of the population (Table 6) (ABS, 2011). Of these people, 90 per cent were of Aboriginal origin only, 6 per cent were of Torres Strait Islander origin only, and 4 per cent identified as both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander in origin. These proportions have changed very little in the last 10-year period. In the Northern Territory, just fewer than 27 per cent of the population identified and were counted as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin in the 2011 Census. In all other jurisdictions, 4 per cent or less of the population were of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. Victoria has the lowest proportion of Aboriginals at 0.7 per cent of the state total (see Table 6).

Table 7 on page 46 provides a further breakdown of the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living within the cities or remote areas of the country. In the 2011 census, one-third (33 per cent) of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population lived in Capital City areas. States with relatively high proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living in Capital Cities include South Australia (51 per cent) and Victoria (47 per cent). In contrast, 80 per cent of the population who identified as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin, and who were counted in the Northern Territory, lived outside the Capital City area (ABS, 2011a). Likewise, in Queensland, 73 per cent of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population lived outside the Capital City area.

Crime and victimization

ABS (2011) presented data on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Offenders for New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia and the Northern Territory. The data reveals that offenders who identified as being Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander accounted for 71 per cent of offenders in the Northern Territory, 18 per cent in Queensland, 13 per cent in South Australia and 12 per cent in New South Wales. However, when the offender rates per 100,000 persons aged 10 years and over are taken into consideration, South Australia had the highest offender rate per 100,000 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons at eight times the non-Indigenous offender rate. The ratio of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander to non-Indigenous offender rates in New South Wales, Queensland and the Northern Territory was approximately six times higher than the non-Indigenous rates.

In 2008, ABS conducted the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS). The survey focuses on a range of factors including personal safety. In 2008, 23 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reported being a victim of threatened or physical or violence in the past 12 months, similar to the rate in 2002 (24 per cent). In 2008, 15 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 years and over had been arrested in the last five years either once, or more than once. This rate was higher in remote (19 per cent) than non-remote (14 per cent) areas. In the area of neighbourhood and community problems, 71 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 years and over reported the presence of at least one neighbourhood or community problem in their area (ABS, 2008).

The ABS (2011a) reported that male and female victims of assault who identified as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin experienced victimization at a higher rate in New South Wales, South Australia and the Northern Territory than male and female victims who identified as non-Indigenous. The ABS further described that male victims who identified as being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin experienced incidents of assault: more than twice the rate of male victims who were non-Indigenous in New South Wales (2,051 per 100,000 compared to 997 per 100,000); three and a half times the rate of male victims who were non-Indigenous in South Australia (3,497 per 100,000 compared to 975 per 100,000); and more than twice the rate of male victims who were non-Indigenous in the Northern Territory (2,955 per 100,000 compared to 1,337 per 100,000). Female victims who identified as being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin experienced incidents of assault: almost five times the rate of female victims who were non-Indigenous in New South Wales (3,707 per 100,000 compared to 742 per 100,000); more than 11 times the rate of female victims who were non-Indigenous in South Australia (8,588 per 100,000 compared to 750 per 100,000); and more than 11 and a half times the rate of female victims who were non-Indigenous in the Northern Territory (9,770 per 100,000 compared to 837 per 100,000).

Willis (2011), in his study of violence in indigenous communities noted that, overall, Indigenous people experience violence (as offenders and victims) at rates typically two to five times those experienced by non-Indigenous people, and this can be much higher in some remote communities as in the other countries examined. Similar results were found by Bryant and Willis (2008) where victimization tends to arise out of the confluence ofseveral risk factors (e.g., socio-demographic variables, measures of individual, family and community functionality; and resources available to a person, including material resources, employment, education, housing mobility and the influence of living in remote or non-remote areas). Bryant and Willis concluded that these factors increased the risk of violent victimization among indigenous people in the same ways as in the non-Indigenous population. However, factors such as the consumption of alcohol, cultural disruptions, residing in remote communities, the function of the community, and social structures have particular impact on violence far greater than those found in non-Indigenous communities.

Wundersitz (2010) found that Indigenous people are 15 to 20 times more likely than non-Indigenous people to commit violent offences. The main risk factors linked to violent offending by Indigenous people include alcohol misuse, illicit drug use, age, sex, education, income, employment, housing, physical and mental health, childhood experience of violence and abuse, exposure to pornography, geographic location and access to services. However, the use of alcohol stands out as a core problem well above structural factors such as socioeconomic disadvantage.

Indigenous offenders are substantially over-represented in prison. According to the Bureau of Statistics (2012), the rate of imprisonment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners were 15 times higher than the rate for non-Indigenous prisoners. The highest ratio of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander to non-Indigenous imprisonment rates in Australia was in Western Australia (20 times higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners). Tasmania had the lowest ratio (four times higher for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners).

In terms of the rate of recidivism, proportionally more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners than non-Indigenous prisoners had prior imprisonments. Roughly 74 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners had a prior adult imprisonment under sentence, compared with 48 per cent of non-Indigenous prisoners (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012). Fitzgerald (2009) pointed out that the increase in Indigenous imprisonment is a matter of concern for two reasons. First, the rate of Indigenous imprisonment is now more than 15 times higher than the imprisonment rate for non-Indigenous Australians. Second, in the wake of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADC), all state and territory governments resolved to reduce the over-representation of Indigenous people in prison. Fitzgerald argued that this increase in prison rates may be due to a number of factors, such as a higher rate of bail refusal, an increase in the time spent on remand and changes in the criminal-justice system’s response to offending rather than changes in offending itself.

Finally, the Australian and New Zealand Police Ministers and Commissioners announced that in 2013 they are planning to review the implementation of community policing models in Indigenous communities.Footnote 9Indigenous policing

Unlike Canada and the United States, Australia has a relatively highly centralized policing system comprising eight major police services—one for each state and territory—and a federal department. In Australia, as in the United States, each state can enact criminal laws, and there is no federal-state split in sentences or correctional institutions, as there is in Canada. Indigenous policing, therefore, falls primarily under state jurisdiction.

Australian Indigenous policing initiatives tend to focus on relations between Indigenous people and the justice system, especially the police, and—unlike Canada and the United States—not on the development of independent stand-alone police services. No such services exist, but there have been attempts to develop contingents of Indigenous auxiliary/liaison police officers within existing state and territorial police services.

Throughout the course of Australian history, police services were used to apply various government policies and laws to Indigenous people. This treatment culminated in the 1987 RCIADIC, a federal inquiry comparable in significance to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP, 1996) in Canada. The RCIADIC was a watershed event in the relationship between Indigenous Australians and the justice system, and propelled wider discussions of Indigenous self-policing, hiring Indigenous police officers in the various police services, and attitudes toward Indigenous people of police personnel, others in the criminal justice system and Australians in general (Samuelson, 1993, Cunneen, 2001a).

In 2007, the Council of Australian Governments agreed to several targets to “Close the Gap in Indigenous Disadvantages” by improving outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The focus was on six specific targets including one called Safe Communities. The Safe Communities target states: “[I]ndigenous people (men, women and children) need to be safe from violence, abuse and neglect. Fulfilling this need involves improving family and community safety through law and justice responses (including accessible and effective policing and an accessible justice system), victim support (including safe houses and counselling), child protection and also preventative approaches. Addressing related factors such as alcohol and substance abuse will be critical to improving community safety, along with the improved health benefits to be obtained (COAG, 2012:7).” In 2012, the government announced that as part of the Australian government's budget initiatives to close the gap in community safety, they will continue funding 60 remote-area police officers, four remote-area police stations and community night-patrol services for the next 10 years (Macklin, 2012), as part of the remote-service delivery model.

In addition, the Standing Committee of Attorneys' General Working Group on Indigenous Justice introduced the National Indigenous Law and Justice Framework for 2009-2015. The Framework provides a national approach to addressing discrimination and disadvantage faced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the justice systems, through a whole-of-government and community partnership approach to law and justice issues (Standing Committee of Attorneys' General Working Group on Indigenous Justice, 2010). Under the framework, strategies are developed to build the capacity for police to address systemic racism and to provide better training to the police to “reduce the negative contact of Indigenous women, men, and youth” (Standing Committee of Attorneys' General Working Group on Indigenous Justice, 2010).

In response and compliance to the RCADIC, many of the states and territories have implemented similar policing strategies or initiatives that focus on reducing Indigenous involvement in the criminal-justice system. These include:

- Night patrols: a common feature of Indigenous communities throughout Australia. Night patrol takes on various names such as street patrols, night patrols, foot or barefoot patrols, street beats, or mobile-assistance programs (Beacroft et al., 2011). Night-patrol activities involve breaking the cycle of violence and crime for people at risk of either causing, or becoming a victim of, harm. According to the Attorney General's Department Northern Territory (2010), the approach is to minimize harm by providing non-coercive intervention strategies to prevent anti-social and destructive behaviours, through the promotion of culturally appropriate processes around conflict resolution in conjunction with contemporary policing measures.

- Indigenous-Police Relations: This involves various programs, such as aboriginal and multicultural units (Australasian Police Multicultural Advisory Bureau, 2003), the appointment of Aboriginal Liaison Officers and Police Aboriginal Community Liaison Officers, Aboriginal Community Justice Panels, police programs such as participating in community activities (e.g., camps, marathons), or police receiving training and education to improve the relationship between the police and Aboriginal people (Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, 2011; Putt, 2010).Footnote 10

- Indigenous Recruitment: Police organizations are reaching out through various programs to recruit Indigenous people. For example, New South Wales Police Force has implemented the IPROWD program, a partnership among the police, a college, and the federal government that customizes training programs to assist Aboriginal people to gain entry to the police college (NSW Police, 2010). Northern Territory Police, along with fire and emergency services, are involved with an Indigenous Employment and Career Development Strategy. The Australian Federal Police have a program called Malunggang Indigenous Officers Network, a voluntary internal network to provide support to recruits, and retention and career development to Aboriginal and Torres Islander individuals. The Australian Federal Police also have an Indigenous Employment strategy to ensure a more consistent approach to Indigenous recruitment and retention.

- Crime Prevention: This includes the introduction of various programs to reduce the level of crimes committed by and against Aboriginal people. However, no research is available to determine the effectiveness of these programs.

The following section will be a descriptive examination of the various Indigenous-policing initiatives that appears to be unique to each state and territory.

Police expenditures

Police services for Indigenous communities are funded through an inter-governmental agreement called the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA).Footnote 11 The objective of the NIRA is to take an inter-governmental approach to "close the gap in Indigenous disadvantage" (COAG, 2012:3).Footnote 12Under the agreement, the State and Territory governments contribute 71 per cent and the Commonwealth contributes 29 per cent. Recently, the NIRA were amended to enhance reporting against Indigenous-specific indicators to measure progress against the Closing the Gap targets. However, no specific police-service performance measures were listed as part of the Agreement. The Allen Consulting Group (2010) pointed out the challenges of establishing measures for performance metrics in some Indigenous communities, including the reliance on quantitative (offence) data that seldom exists, the use of incident data which is not clearly reported, the lack of quality data at the community level (e.g., population numbers) and the lack of statistical variation between communities.

The Indigenous Expenditure Report Steering Committee published police expenditures for Indigenous communities for the year 2008-2009.Footnote 13 Table 8 below provides the total expenditure for police service for Indigenous population. During that year, the Australian, state and territory governments spent around $1 billion on policing services for the Indigenous population. In comparison, the governments spent $4.2 billion for policing services in non-Indigenous populations. However, when population of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous are taken into consideration, more monies per person are spent on Indigenous population than on Non-Indigenous population.

| Expenditures for Police Services | NSW | Vic | Qld | WA | SA | Tas | ACT | NT | Aus Gov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Population | 216, 918 | 66,598 | 237,133 | 152,775 | 70,375 | 20,346 | 8,575 | 145,478 | 311,110 |

| Non-indigenous Population | 2, 014, 105 | 1,300,983 | 1,249,170 | 592,176 | 531,789 | 162,570 | 115,698 | 65,580 | 144,931 |

Source: Indigenous Expenditures Report Steering Committee (2010; Table I.1)

Table 9 below provides an overview of the expenditure per head of population for Indigenous and non-Indigenous. Government expenditure per head of population on police services was estimated to be $1,613 per Indigenous person and $295 per non-Indigenous person. South Australia spends the most per Indigenous person ($2,387) (or 447% higher than for a non-Indigenous person). In terms of dollars spent person, it is estimated that on average, $5.29 was spent per Indigenous person for every dollar spent per non-Indigenous person in the population. These figures have several important caveats: Providing services to Indigenous Australians costs more because of remoteness, the higher expense of limited services, and policing costs that may also be reported under other justice costs (i.e., court costs) (IERSC, 2010a).

| Expenditure per head of population for Police Services | NSW | Vic | Qld | WA | SA | Tas | ACT | NT | Aus Gov |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indigenous Population | 1,353 | 1,876 | 1,535 | 2,059 | 2,387 | 1,047 | 1,886 | 2,175 | 196 |

| Non Indigenous Population | 291 | 243 | 297 | 277 | 336 | 338 | 336 | 421 | 116 |

| Ratio * | 4.64 | 7.71 | 5.17 | 7.43 | 7.11 | 3.10 | 5.61 | 5.17 | 1.69 |

* The ratio of total Indigenous expenditure per person to total non-Indigenous expenditure per person. This reflects the combined effects of differential use patterns and costs between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Source: Indigenous Expenditures Report Steering Committee (2010; Table I.2: page 346)

Police performance

Recently, the NIRA was amended to enhance reporting against Indigenous-specific indicators to measure progress against the Closing the Gap targets. However, no specific police-service performance measures were listed as part of the Agreement. The Allen Consulting Group (2010) pointed out that the challenges of establishing measures for performance metrics in some Indigenous communities include the reliance on quantitative (offence) data that seldom exist, the use of incident data that are not clearly reported, the lack of quality data at the community level (e.g., population numbers) and the lack of statistical variation between communities.

New South Wales

The New South Wales Police Force has developed an Aboriginal Strategic Direction which focuses on how to deliver policing services to the Aboriginal community of New South Wales. The four key priority areas are:

- Ensure community safety.

- Improve communication and understanding between police and Aboriginal people.

- Reduced involvement and improved safety of Aboriginal people in the criminal- justice system.

- Reduction and diversion from harm (New South Wales Police Force (2012).

Under each of these areas, a series of outcomes, action, indicators of success, accountability and reporting are provided.

The New South Wales Police Force in partnership Community Services and NSW Health Professionals have established Joint Investigation Response Teams (JIRTs) that focus on investigation of child-protection matters. Under this mandate, JIRTS established community-engagement guidelines on how to proactively engage Aboriginal communities (Joint Investigation Response Team, 2008). The objectives are to improve how the JIRT agencies engage with Aboriginal communities, and consequently build greater cooperation, commitment and capacity in the communities to address serious child abuse and neglect issues.

Finally, the police force, in partnership with Crime Stoppers and the Aboriginal Land Council, established a program called, “we're watching you.” The program provides a $5,000 reward for information about the sexual exploitation of Aboriginal children. The focus of the program is along major trucking routes and highways.

Victoria

In response to the RCIADC, the Victorian Government, in partnership with the Koori community established the Victorian Aboriginal Justice Agreement (AJA). The AJA aims to minimize Koori over-representation in the criminal-justice system by improving accessibility, utilization and effectiveness of justice-related programs and services, in partnership with the Koori community. The AJA consisted of two phases: one introduced in 2000, and phase two launched in 2006. Under phase two, the Victoria Police are the lead agency responsible for the following initiatives: