ARCHIVE - 2006-2007 Formative Evaluation of the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet

Archived Content

Information identified as archived is provided for reference, research or record-keeping purposes. It is not subject to the Government of Canada Web Standards and has not been altered or updated since it was archived. Please contact us to request a format other than those available.

Adobe Acrobat version (PDF 1.14MB)

Prepared for

Public Safety Canada

Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Industry Canada

Prepared by

Public Works and Government Services Canada

Project No.: 570-2651

June 2007

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- 1. Overview

- 2. Findings and Conclusions – Horizontal Level

- 3. Findings and Conclusions by Component

- 4. Recommendations

- Appendix A: Logic Model

- Appendix B: List of Documents Reviewed

- Appendix C: Interview Guides

- Appendix D: Budgets and Expenditures by Initiative Partner

- Appendix E: Resource Implementation Status

List of Acronyms

| ADM | Assistant Deputy Minister |

| CAIP | Canadian Association of Internet Providers |

| CCAICE | Canadian Coalition Against Internet Child Exploitation |

| CCJS | Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics |

| CETS | Child Exploitation Tracking System |

| DoJ | Department of Justice |

| FPT | Federal/Provincial/Territorial |

| GCS | Government Consulting Services |

| IBCSE | Internet-based Child Sexual Exploitation |

| ICE | Integrated Child Exploitation (unit) |

| ISP | Internet Service Provider |

| IWG | Interdepartmental Working Group |

| NCECC | National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre |

| NGO | Non-Governmental Organization |

| NSPCSEI | National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet |

| NST | National Steering Committee |

| PIPEDA | Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act |

| PS | Public Safety Canada |

| RCMP | Royal Canadian Mounted Police |

| RMAF/RBAF | Results-based Management and Accountability Framework / Risk-based Audit Framework |

| VGT | Virtual Global Taskforce |

[ * ] - In accordance with the Privacy and Access to Information Acts, some information may have been severed from the original reports.

Executive Summary

i) Introduction

The National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (NSPCSEI) is a horizontal initiative providing a comprehensive, coordinated approach to enhancing the protection of children on the Internet and pursuing those who use technology to prey on them. A total of $42 million over five years, beginning in 2004-2005, was allocated to three Initiative partners to implement the three core objectives of the overarching National StrategyNote 1. The table below lists the Initiative partners and summarizes the funding that was provided for each partner.

| NSPCSEI Partner | Funding Level over Five Years |

|---|---|

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) | $34.34 M |

| Industry Canada | $3.00 M |

| Public Safety (PS) | $1.20 M |

|

$3.50 M |

| TOTAL | $42.04 M |

Under the NSPCSEI, the general expectations and desired achievements of each partner were as follows. Funding for the RCMP was directed towards the expansion of the current capacity of the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC). Industry Canada received funding to expand SchoolNet and forge partnerships with industry and NGOs. PS was to enter into a contribution agreement with Child Find Manitoba for the purposes of operating and expanding their Cybertip.ca program. In addition to the contribution agreement funding, as the lead department for the NSPCSEI, Public Safety received funding to fulfill its coordination, oversight and evaluation role and responsibilities.

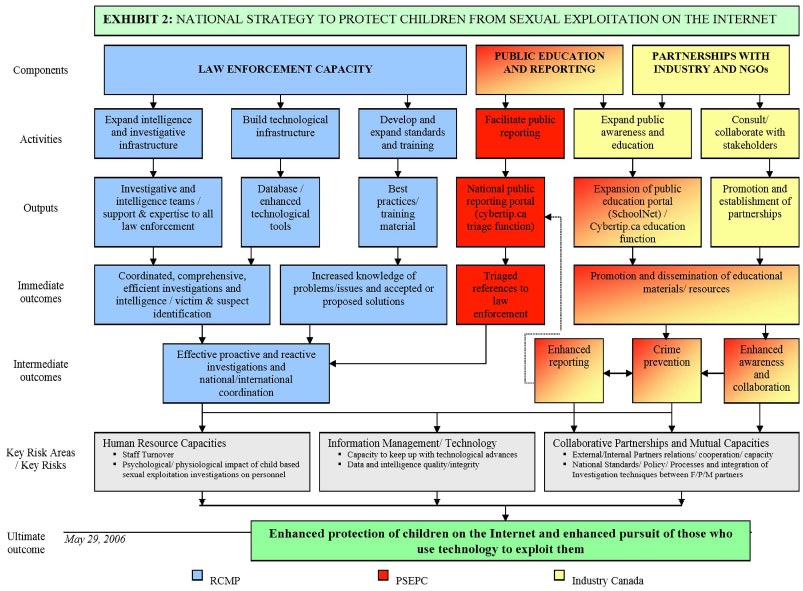

Through the collaboration of all partners, a Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework (RMAF/RBAF) was prepared for the NSPCSEI in order to establish accountabilities, guide performance monitoring, audits and evaluations. In the RMAF/RBAF, the logic model is organized around three Initiative components as follows:

- Law Enforcement Capacity

- Public Education and Reporting

- Partnerships with Industry and Non-government Organizations (NGOs)

As outlined in the integrated RMAF/RBAF, the objective of this study, conducted by Government Consulting Services (GCS), was to prepare a formative evaluation report for the NSPCSEI Initiative. The formative evaluation sought to measure success to date, identify challenges and gaps in the implementation of the Initiative and allow partners to adjust accordingly. A summary of conclusions and recommendations resulting from this study is contained in the following two sections.

ii) Summary of Conclusions

Horizontal Level

At the horizontal level, the linkages between activities and outcomes in the logic model remain valid. However, the logic model would better reflect the multi-dimensional nature of the overall problem of internet based child sexual exploitation if the elements of legislation, research and international aspects were included on the logic model.

In terms of oversight and governance, although a formal ADM Committee has not been established, partners continue to brief their executive levels as necessary. The current governance mechanisms, at the operational level do not provide an adequate forum to solve strategic and operational issues that require the attention of several partners. In addition, there appears to be greater collaborative synergy at the working level than at the executive level, likely due to an unusual level of dedication and resourcefulness of employees at the working level. The specialized committees, at the working level, have proven to be effective in tackling well-circumscribed dimensions of the larger problem. With the exception of roles related to awareness activities, the current roles and responsibilities are clear to partners.

In terms of adequacy of resources, Cybertip.ca has experienced an unexpected increase in reports and is under-funded to respond. Furthermore, efforts to reduce backlogs at NCECC and the triage function of Cybertip.ca have increased the current volume of cases being referred to the field; as such, field capacity cannot meet the demand being created. In terms of financial resource management, PS and Cybertip budgets versus expenditures have been within acceptable limits over the last three years. The variances of expenditures against budgets for Industry Canada and the RCMP are not within acceptable limits, suggesting that funding has not been well managed by these two Initiative partners.

Law Enforcement Capacity

Activities and outputs related to the Law Enforcement Component are nearing full implementation. Outstanding issues remain that are hampering the full implementation of the image database.

Law enforcement is benefiting from the increased number of personnel at the NCECC through an eliminated file backlog, expeditious file referrals, sharing of information through conferences and publications, and training delivery. CETS has potential but has achieved limited success to date. Adjustments are required to ensure greater use of CETS, particularly since it is not well supported in terms of data entry.

Public Education and Reporting

CyberWise.ca and Cybertip.ca have implemented awareness activities and outputs as planned. The Cybertip.ca national awareness campaign has proven to be effective, and public awareness activities have made a difference. Despite this, there is room for improvement. The Initiative does not have an overall communication strategy, and multiple Web resources are provided by the Initiative partners, and by other organizations, working on the same problem. Linkages among partner websites to the CyberWise site are weak. In-person presentations are popular, and all partners have reported not being able to keep up with the demand. Finally, all partners agree that more audiences from other groups must be targeted. These audiences include the health sector, social welfare workers, the judicial system and parliamentarians.

All partners see the reporting process as working well and view Cybertip.ca as an invaluable partner.

Partnership with Industry and NGOs

Activities and outputs of the Partnerships with Industry and NGOs have generally been implemented as planned, extending the reach of individual delivery partners beyond an otherwise limited scope of public involvement. Industry Canada has faced some challenges providing national coverage due to limited funding. In addition, unanticipated partnerships such as CCAICE have developed, contributing somewhat to resolving otherwise conflicting interests of law enforcement and industry.

iii) Recommendations

The recommendations provided are related to the conclusions presented throughout the report. They are presented by evaluation issue area. Each recommendation includes a bracketed reference indicating to which partner(s) the recommendation is directed.

Design and Delivery

1. The logic model and RMAF/RBAF should be revisited and possibly revised to include legislative, research and international facets/ components of the child exploitation issue that were not part of the original Initiative design, but are currently being undertaken by partners. In addition, each of the three existing logic model components contain missing activities that are not supported at this time.

- Law Enforcement Component: Forensics,child sex crime investigations and covert operations.

- Public Education and Reporting Component: A communication strategy that targeted at specific audiences on specific dimensions of IBCSE. Audiences could include: lawyers and judges on issues such as the fact that Internet-based child exploitation is not a “victimless crime” simply because it involves images; the health sector; parliamentary committees and decision-makers. Finally, there is a need for a targeted communication strategy on PIPEDA and lawful access, which could include an awareness strategy for ISP providers and credit card companies.

- Partnerships with Industry and NGOs Component: Federal/provincial/territorial collaboration is desired to provide a unified approach.

A Memorandum to Cabinet may be required to seek funding for these aspects of the Strategy that are required in order to accommodate the multi-dimensional nature of this issue. (all partners)

2. The governance of the Initiative should be strengthened. A stronger central forum is required to address shared strategic and operational issues that cannot be solved by individual partners. Clear terms of reference should be developed for each committee or sub-committee, including the National Steering Committee and the IWG; and the membership of these groups should be carefully considered in terms of what participation, at what level of each organization, will make them function well. (PS in consultation with all partners)

3. Industry Canada and the RCMP should seek a mechanism to ensure better financial management so that funds do not lapse in future years. (Industry Canada, RCMP)

Success

4. Although the volume of reports being triaged through Cybertip.ca and the expeditious file referrals through the NCECC have allowed cases to be efficiently forwarded to field investigators, it appears that the volume of work cannot be addressed at the field level given the current resource levels. Therefore, the RCMP should work with ICE units and provincial partners to examine and quantify resource requirements, in order that resource levels can be properly set to support the required investigations. (RCMP)

5. The NCECC should seek to provide better service to regions that are a significant geographic distance and time zones away from their operations. This should include gaining an understanding of what service level is expected by outlying regions, and a communication to those regions of what can be realistically accommodated beyond the provision of the offer of 24/7 on-call service. It should also include training material that is focused on the regional requirements. (RCMP)

6. CETS requires more data entry capability, ease of access and better technical support if the system is to reach its desired achievements. The RCMP should quantify the resources for this and shift funds to accommodate the requirement. (RCMP)

7. An overarching Communication Strategy should be prepared for the Public Education and Awareness activities. The Strategy should include a clarification of roles and responsibilities among Cybertip.ca, CyberWise.ca and the RCMP; considerations for the provision of national coverage, including French language material; and the inclusion of stakeholders such as the health sector, social welfare workers, members of the judicial system and parliamentarians. The Communication Strategy could assist in quantifying the level of funding that is necessary for Public Education activities and understanding where leverage could be realized. (Industry Canada in consultation with partners)

1. Overview

1.1 Report Structure

This formative evaluation report is divided into four sections:

- Section 1 provides an overview and background on the National Strategy for the Protection of Children from Sexual Exploitation on the Internet (NSPCSEI), a description of the evaluation framework and description of the objectives of the formative evaluation, an explanation of the methodology used to conduct the evaluation and, finally, a listing of limitations related to the study;

- Section 2 provides findings and conclusions related to the Design and Delivery of the Initiative at the horizontal level;

- Section 3 provides findings and conclusions from all lines of inquiry of the evaluation, organized by the evaluation issue areas of Design and Delivery, and Success. This section is broken down by the Initiative’s components: Law Enforcement Capacity, Public Education and Reporting, and Partnerships with Industry and NGOs;

- Section 4 presents recommendations for improvement for the NSPCSEI

1.2 Introduction and Background

The NSPCSEI is a horizontal initiative providing a comprehensive, coordinated approach to enhancing the protection of children on the Internet and pursuing those who use technology to prey on them. While the Strategy itself contains five broad objectives, the Government of Canada Budget Plan 2004 only allocated funding to implement three core objectives centred on law enforcement; public education and reporting; and partnerships with industry and non-government organizations (NGOs).Note 3 These core objectives include a number of principal activities as follows:

- an expanded Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) national coordination centre and enhanced investigational tools;

- a national Internet tip reporting line (Cybertip.ca); and,

- an enhanced SchoolNet program through Cyberwise.ca.

A total of $42 million over five years, beginning in 2004-2005, has been allocated to three Initiative partners to implement the three core objectives of the Strategy. In support of their core objective to enhance law enforcement capacity, the RCMP received a total of $34.34 million over five years. The funding was directed towards the expansion of the current capacity of the National Child Exploitation Coordination Centre (NCECC) which is key to achieving this core objective. Industry Canada received a total of $3 million over five years to expand SchoolNet and forge partnerships with industry and NGOs.

Public Safety Canada (PS) received a total of $3.5 million over five years ($700,000 annually) in federal base funding to enter into a contribution agreement with Child Find Manitoba for the purposes of operating and expanding their Cybertip.ca program. In addition to the contribution agreement funding, as the lead department for the NSPCSEI, Public Safety received $1.2 million over five years for the purposes of fulfilling its coordination, oversight and evaluation role and responsibilities.

The table below summarizes the funding that was provided for each Initiative partner.

| NSPCSEI Partner | Funding Level over Five Years |

|---|---|

| RCMP | $34.34 M |

| Industry Canada | $3.00 M |

| PS | $1.20 M |

|

$3.50 M |

| TOTAL | $42.04 M |

1.3 Overview of the Evaluation Framework

At the outset of the NSPCSEI Initiative, partners collaborated on the preparation of an integrated Results-based Management and Accountability Framework and Risk-based Audit Framework (RMAF/RBAF) in order to establish accountabilities, guide performance monitoring, audits and evaluations. The logic model for the Initiative, found at Appendix A, is organized around three Initiative components as follows:

- Law Enforcement Capacity

- Public Education and Reporting

- Partnerships with Industry and Non-government Organizations (NGOs)

As outlined in the integrated RMAF/RBAF, two evaluations, to be coordinated and led by PS, were to be undertaken to assess the overall impact results of the NSPCSEI. This report represents the key deliverable of the mid-term (i.e., formative) evaluation. Also specified in the RMAF/RBAF, a summative evaluation of the NSPCSEI will be presented to Treasury Board Secretariat no later than June 30, 2008, after which Treasury Board Secretariat will determine the ongoing nature and level of funding for the Initiative beyond that year.

1.4 Evaluation Objectives and Questions

The overall objective of GCS’s assignment was to conduct a formative evaluation of the NSPCSEI. The formative evaluation questions and analyses focus on the design and delivery aspects of the Initiative as well as early success and likelihood of achieving intermediate and ultimate outcomes. In addition, the formative evaluation examines the effectiveness of the NSPCSEI in its current structure, roles and functions, and identifies internal and external influences on performance of the NSPCSEI to date. The formative evaluation seeks to measure success to date, identify challenges and gaps in the implementation of the Initiative so that partners can adjust accordingly.

The following specific evaluation questions, contained in the integrated RMAF/RBAF are answered in this formative evaluation report:

Design and Delivery Questions

- Is there a logical relationship between the Initiative’s activities and expected outcomes?

- To what extent has the Initiative’s formal oversight function proven to be effective?

- To what extent has implementation of the Initiative been coordinated?

- Has PS’s coordination and secretariat support function to the ADM Committee been effective?

- Are allocated resource levels reasonable based upon the scope of the Initiative and the identified need?Note 5

- Have the Initiative’s activities been implemented as expected?

Success Questions

- To what extent has the NCECC facilitated information/intelligence gathering and sharing?

- To what extent have “enhanced investigational tools” (e.g., image database, CETS) strengthened law enforcement capacity?

- To what extent have partnerships with private industry and NGOs resulted in effective public awareness, education and/or crime prevention strategies?

- To what extent has SchoolNet become a clearinghouse of educational resources related to IBCSE?

- To what extent has the expansion of Cybertip.ca resulted in a national IBCSE reporting centre/portal?

- Is Cybertip.ca mitigating the number of IBCSE complaints/reports received by Canadian law enforcement?

- Are Canadians becoming aware of where, when and what to report as IBCSE?

1.5 Methodology

This assignment involved several lines of inquiry, including document review, interviews and review of quantitative information. The approach adopted is detailed in the following list of activities undertaken by the GCS team:

Preparation of Data-gathering Tools: Based on the RMAF/RBAF, GCS developed interview guides, document review templates and templates to capture quantitative data.

Document Review and Review of Quantitative Information: GCS reviewed documents provided by the three partners and by Cybertip.ca. GCS then conducted an analysis of quantitative data and extracted relevant information. The list of documents reviewed can be found at Appendix B.

Interviews: Using the developed guides, found at Appendix C, GCS conducted 34 interviews. Specifically, interviewees included representatives from the Interdepartmental Working Group, program managers and staff for the NSPCSEI in PS, RCMP and Industry Canada, representatives of Cybertip.ca (a funded non-government organization based in Winnipeg), law enforcement members of the Integrated Child Exploitation (ICE) units and delivery agents of the SchoolNet program (as funded through Industry Canada). The interview distribution was as follows:

- program management and oversight: 10 interviews with all federal partners

- program delivery: 10 interviews, including all federal partners and Cybertip.ca

- delivery partners: 14 interviews, including Industry Canada SchoolNet partners, Integrated Child Exploitation (ICE) units and one Internet Service Provider (ISP)

Analyze Data and Report Production: Using information gathered during the document review, interviews and review of quantitative data, GCS analyzed the findings according to each evaluation issue and question. GCS prepared a preliminary deck of findings for presentation to the Interdepartmental Working Group and provided a draft report for review on March 29, 2007.

1.6 Study Limitations

Although multiple perspectives were sought during the interviews, the low number of interviewees within some of the groupings sometimes made it difficult to find a consensus of opinion, e.g., Internet Service Providers were only represented by one interviewee.

2. Findings and Conclusions – Horizontal Level

2.1 Design and Delivery

Several aspects of the issue area of Design and Delivery, for the Initiative as a whole, were examined during the evaluation. These are as follows:

- the extent to which there is a logical relationship between the Initiative’s activities and expected outcomes;

- the extent to which the Initiative’s formal oversight and coordination functions for the horizontal management have proven to be effective; and

- whether resource levels are sufficient to meet the need.

2.1.1 Findings

(i) Logical Relationship between Activities and Outcomes

- Program managers and delivery partners indicated that the logic model continues to reflect the original identified need for the Initiative, and the ultimate outcomes remain valid. However, to fully address the problem, interviewees identified a need to address noted deficiencies in the logic model itself. That is, as outlined below, the legislative, research and international aspects of the fight against IBCSE are being addressed through various means by Initiative partners, but they are not reflected on the logic model. These aspects strengthen the Initiative and should be included on the logic model. These aspects include the following:

- Legislative: Two-thirds of program management and oversight interviewees suggested that a legislative component be included in the logic model since [ * ]. The NCECC collaborates regularly with ICE investigators across the country and has established a legislative wish list which would facilitate the investigation and prosecution of internet facilitated child exploitation such as Internet Industry regulation including mandatory reporting, cooperation with law enforcement and data retention, pro-active use of the National Sex Offenders Registry (NSOR), raising the age of consent and a database of non facial images of charged persons. The NCECC suggested that DoJ participate in conducting relevant legislative and legal research and analysis. They suggest establishing a centre/clearinghouse for Case Law specifically tailored to IBCSE and greater collaboration among partners to tackle key legislative issues such as: issues surrounding the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA); the Sex Offender Information Registration Act (SOIRA); the development of guidelines / protocols on handling child pornography and evidence; and legal issues pertaining to the use of international image databases and victims’ rights. The NCECC legislative wish list includes the possibility of Canadian DNA legislation and the allowance for photos of offenders’ identifiable physical features that can be matched with biological data. During the interviews, the NCECC requested a team approach to the legislative issues, believing that each partner should bring their perspective to the table and demonstrate equal ownership of this issue

- Research: The NCECC conducts operationally focused research. Subjects include the relationship between on line and off line offences in order to refute misconceptions that IBCSE is a victimless crime; accidental discovery; and pro-abuse ideology. The research provides information on youth trends to assist with undercover operations; technology trends to assist investigators; and monitors the Impact on Investigator Emotional Wellness. Despite these efforts, interviewees indicated that statistics on cybercrime and child sexual exploitation related crime are required to support awareness; a communication strategy and strategic planning are also required. Data are required to demonstrate the issue to decision-makers such as parliamentary committees. Industry Canada indicated that statistics from Statistics Canada would be beneficial in determining more accurately the needs by province. Interviewees noted that existing databases, such as Cybertip.ca and the DoJ Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics (CCJS) could be capitalized upon to conduct trend analysis and situational research. Cybertip.ca also indicated that its database has a wealth of information that could be mined to assist in developing targeted education and awareness material; however, it is currently not resourced to conduct this activity.

- International: The international aspects of IBCSE are not currently represented on the logic model. With respect to International collaboration, the NCECC participates daily with international partners in the identification and location of victims and offenders. Secure networks allow the NCECC to work on international cases. Participants indicated that although much work and collaboration has been done to building international partnerships in the efforts against IBCSE, there is a need to build greater relationships with Interpol, Foreign Affairs and International Trade Canada, and the Virtual Global Taskforce (VGT).

Interviewees also identified several areas of the logic model that could be revisited because, although the upper level components are represented on the logic model, essential activities are missing. Additionally, it was suggested that reorganization of the components may be beneficial. The suggestions were as follows, listed by logic model component:

- Law Enforcement Component: Forensicsis an important activity which needs to be represented in the logic model and in the field. Interviewees would like to implement a “Centre of Excellence approach.” Additionally, the RCMP thinks that the logic model could include related activities, such as child sex crime investigations and covert operations.

- Public Education and Reporting Component: In terms of education and awareness activities, a communication strategy is desired that identifies approaches targeted at specific audiences on specific dimensions of IBCSE. First, interviewees indicated that there is a need to raise awareness among lawyers and judges on issues such as the fact that Internet-based child exploitation is not a “victimless crime” simply because it involves images; at the end of the day, children are being harmed. Second, interviewees identified the health sector is an important audience and potential partner in fighting IBCSE. Anecdotal evidence, derived from the interviews, pointed to the fact that nurses, social workers and physicians need to be well aware of thisform of child exploitation in order to rapidly detect it and to report it to the appropriate authorities. Third, parliamentary committees and decision-makers need to more fully understand the scope and the nature of the problem in order to appropriately address the issue. Finally, there is a need for a targeted communication strategy with respect to PIPEDA and lawful access. There are misunderstandings about what lawful access really is, and it has been twisted by the media, which is causing ongoing media relations issues for NCECC. Targeted communications on lawful access could also include an awareness strategy for ISP providers and credit card companies.

- Partnerships with Industry and NGOs Component: Interviewees noted the requirement to include federal/provincial/territorial collaboration in the logic model. Coordination with the provinces and provincial law enforcement agencies is desired because there is a lack of interoperability internally to share information related to cases and investigations. To this end, NCECC is currently looked to as a coordinating and leadership body where a number of jurisdictions are involved, nationally and internationally. Further, interviewees expressed a desire for a more comprehensive and inclusive national approach (i.e., law enforcement involvement in strategic planning, provincial participation). As a final note, the ISP interviewee noted that a federal/provincial/territorial partnership and coordination is desirable so that ISPs themselves do not receive mixed messages from different levels of government.

As a final point,Cybertip.ca underlined that, because the Initiative is focused on the Internet aspects of the crime, it does not properly reflect the reality that the Internet is only a channel that facilitates the propagation of child abuse. The actual crimes take place in the off-line world; therefore, prevention activities are paramount in addressing the issue. Within the Initiative’s logic model, the idea of “awareness” is currently reflected; however, real prevention activities need to move beyond awareness of Internet safety in order to attempt to prevent abuse at the root of the problem. Consequently, Cybertip.ca is looking at a more encompassing approach to deal with child abuse and child pornography in the development of their educational material.

(ii) Initiative Oversight and Horizontal Coordination

The RMAF/RBAF for the Initiative outlined several mechanisms for Initiative oversight and horizontal communications. First, the lead department for the NSPCSEI Initiative is PS which received $1.2 million over five years for the purposes of fulfilling its overall oversight, coordination, research and evaluation functions. PS’s role was to a) support the ADM Steering Committee in terms of policy coordination, development and logistics; and, b) provide overall coordination for the implementation of the entire Strategy. Second, according to the original design, the Assistant Deputy Minister (ADM) Steering Committee, comprised of ADMs from each of the partner departments (PS, RCMP and Industry Canada) was seen as necessary to provide overall direction, oversight and advice on events and circumstances that may influence the achievement of expected outcomes. Third, partners were to work collectively through an Interdepartmental Working Group (IWG) to measure, monitor and report on performance and risks against expected outcomes and to maintain NSPCSEI corporate memory in support of knowledge management. Finally, the original design included the National Steering Committee on Internet-based Child Sexual Exploitation (the National Steering Committee) with membership to be comprised of the law enforcement agencies across the country. The implementation and operation of these mechanisms were explored during the evaluation. The findings are presented below.

In terms of the ADM Steering Committee, program managers indicated that this committee did not materialize and that there is no forum for horizontal communication among partner departments. However, partners continue to report and to brief senior management as necessary. During the interview, PS explained that they do not see a need for this oversight function as it was originally envisioned; this comment is debated by other partners of the Initiative.

Coordination of the funded Initiative partners is done though the IWG. Feedback from interviewees illustrated that the IWG had been most active during [ * ] and RMAF/RBAF. Otherwise, it appears that the IWG is an ad hoc committee that has been described as a “check and balance” committee, rather than a joint management committee. For example, the IWG has no defined terms of reference, and each meeting is usually prompted by a need to address a particular issue. The IWG held about half a dozen meetings last year to address issues. According to Industry Canada and PS, the Committee is working well. However, RCMP is relatively displeased with the IWG, believing that more structure and leadership is necessary to improve it. Despite these issues, partners have noted a collaborative synergy at the working level where there is an excellent level of cooperation because in the words of one interviewee, “everyone is committed to the file because of the subject of the file.”

From interviewees’ responses, it appears that the current ad hoc and informal approach does not allow them to properly tackle and alleviate coordination issues and operational challenges that should be handled centrally among partners. Most interviewees agree that national leadership needs to be built into the Strategy. Industry Canada interviewees believe there is lack of support. NCECC interviewees expressed a feeling of isolation and stated that the components of the Initiative are working as silos rather than at a horizontal level. Several mechanisms were suggested to address issues that are most appropriately handled centrally (e.g., solve specific problems, deal with legislative challenges and provide coordinated training, best practices and international cooperation). Some interviewees indicated that they would like PS to play more of a leadership role in this regard. NCECC sees the need being addressed by a joint management team that problem solves together and believes that this would be best accomplished at the DG level so that the ability to work through issues is present, but the members are close enough to have an everyday understanding of the work. Cybertip.ca would like to have monthly meetings with all partners. Finally, interviewees felt that it was necessary to include “unfunded” partners such as DoJ. DoJ believes it is not being kept up to date and sees that there are key issues that are not being tackled because of a lack of formal coordination mechanisms. Therefore, DoJ is asking for more proactive horizontal management that would include unfunded partners.

The National Steering Committee, chaired by the Deputy Commissioner of the National Police Service and the Deputy Commissioner from the Ontario Provincial Police (OPP), has met once or twice per year and was cited by interviewees as a mechanism for broad horizontal management focused mainly on law enforcement activities. Its membership includes funded partners as well as law enforcement stakeholders external to the NSPCSEI partners.

Interviewees stated that the current approach to address partner concerns and issues is ad hoc and inadequate and that the function of the National Steering Committee is that of an updating/briefing forum as opposed to providing a real oversight function. Delivery partners and program managers who take part in this committee described its role as unclear and they see little added value of the National Steering Committee in its present format to work through issues. Some of this confusion could be due to the lack of communication about the NSPCSEI; some interviewees indicated that they had not seen the logic model prior to the evaluation interviews; the National Steering Committee could use the logic model as a primary communication tool to express desired outcomes.

Some delivery partners see the need to include more provincial and municipal partners in the discussions, e.g., Peel Region, Vancouver, Edmonton, Maritimes, Royal Newfoundland Constabulary and Halifax Regional Police. Participants reported a significant decrease in participation in the National Steering Committee meetings (from 70 to 10 since its inception). This decrease was seen mostly from police forces from provinces other than Ontario and Quebec. To address some of these issues and provide an “operational forum” to address issues, the Internet Child Exploitation Officers in Charge (ICE OIC) Committee was established. Members of this committee include Officers in Charge of ICE units across Canada. The Committee meets on average every two months to discuss all relevant subjects. Participants see this group as very valuable and consider it to be an improvement mechanism. Interviewees regard it as “the most important committee for police on the front line” combating child exploitation.

In terms of other coordination mechanisms, interviewees see a strong need for specialized committees to tackle specific dimensions of the overall IBCSE problem. First, they see the benefit of the technology-focused committee, that has already been created, to help coordinate systems development and clarify issues that personnel are having with CETS. This committee meets regularly to discuss issue of common interest for law enforcement agencies. Second, they see the need for a legal subcommittee, such as the one that exists in Ontario, to accomplish such objectives as discussing case law, developing procedures for introducing child abuse images in court, and reviewing legislation. Despite the projected need for the above-mentioned committees, informal and semi-formal coordination mechanisms have been created. As an example, DoJ and NCECC have established an informal process to channel communication. Currently, NCECC is looking at ways to work more closely with Cybertip.ca.

Finally, in terms of effective definition of roles and responsibilities, many expressed that roles and responsibilities of the partners in the horizontal initiative are clearly defined and communicated. The partners see no overlapping of roles and responsibilities. The exception to this is public education and awareness activities where duplications and gaps appear to still exist.

(iii) Resource Levels

All partners, with the exception of the NCECC and PS, indicated that they did not have adequate resources to undertake the activities identified in their component of the NSPCSEI. Cybertip.ca indicated that funding is insufficient to handle the volume of reports that it is currently receiving. Initially, it projected that it would receive 500 reports per month after five years, but it is currently receiving a monthly average of 750-800 reports. Industry Canada’s lack of personnel has forced a selective number of presentations. Interviewees there indicated that they had attempted to deliver one presentation per province, but some provinces, such as Nova Scotia and British Columbia, were difficult to reach. Industry Canada also experienced difficulties in finding French presenters. There is also more work is needed to attain a higher level of partnership. Finally, the NCECC indicated that, although they have sufficient funding to implement their planned activities, they have not gone as far as they would like in supporting big investigations, that it is difficult to keep up with requests for presentations and training and that the resource impacts of CETS in the field seem not to have been considered because the task of adding files to CETS is under-resourced. All partners agree that the current level of funding for the overall Initiative only allows them to address the “tip of the iceberg.”

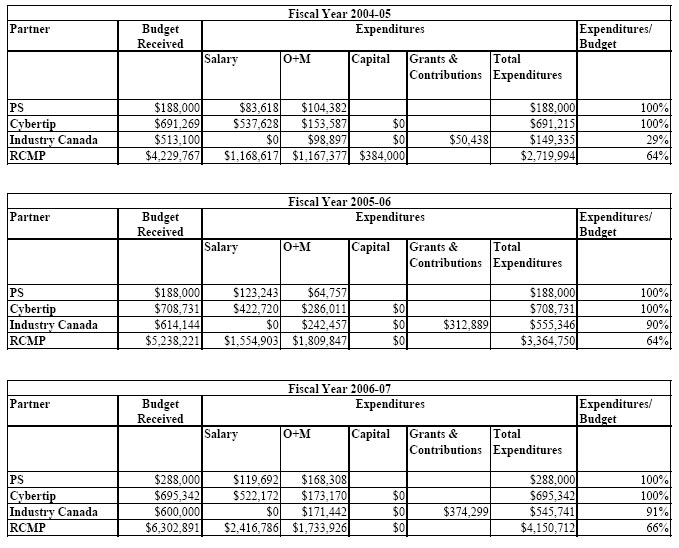

Financial Resource Management

Analysis of quantitative information provided to the evaluation presented an overview of how funding has been managed during fiscal years 2004-05; 2005-06 and 2006-07 by each Initiative partner. A summary of findings is provided below, and details can be found at Appendix D.

The analysis of budgets against expenditures shows that PS and Cybertip expended 100% of funding received, placing spending within acceptable limits. However, expenditures by Industry Canada and the RCMP have not been within acceptable variances over the last three years. Industry Canada under spent its budget by 70% in the start-up year and lapsed 10% of their funds in the following two years. It is noted that, during the first year of Industry Canada's participation in the Initiative, some funds were shifted to cover branch-wide corporate costs (e.g. corporate overhead, technical equipment and support to this equipment, corporate taxes). This would account for some of the 70% difference in expenditures against budget and indicate that some funds had not lapsed but were used for other purposes within Industry Canada. However, in the two following years, funds lapsed by close to 10%.

During the three years studied, the RCMP under spent its budget by around 35% in each of the three years. Explanation for the unexpended funds include the following. The pace of staffing has been slow due to the nature of the work that requires personnel to have the psychological capacity, interest, and suitability to work on child exploitation cases. Many of the suitable candidates had to be relocated from regional offices, and this impacted the timely filling of positions. These vacancies have now been resolved. The use of funding for the development and purchase of the Image Database was also a factor in the management of funds since its development was negatively impacted by a high demand for limited technical support personnel tasked with other high priority projects. Finally, some of the unused funds were transferred to another Division of the RCMP, for a project on Internet Safety, and some funds were used for the National Sex Offender Registry. Therefore, some of the funds were expended for other related purposes, and the amount funding that actually lapsed could not be fully determined from the information provided to the evaluation.

Resources for Awareness Activities

Partners believe that more funding is required for awareness activities. There is a certain level of duplication of efforts for public education, yet, based on findings, there is still a strong probability that extra resources would be needed to:

- Expand public education across all provinces and to stakeholder interest groups (e.g., parents, school boards, health and social welfare communities, etc.)

- Expand public education and awareness on child luring, child intimidation and cyber-bullying

- Prepare age-specific education material for in-school education efforts

- Establish Memorandums of Understanding with school boards and parent association organizations to incorporate the material into their awareness-building activities in the schools

- Establish accountabilities of psychologists and other health care professionals to report IBCSE, within the parameters of related code of ethics and legal responsibilities

- Reach welfare agents

- Educate doctors, nurses and social workers

- Educate lawyers, judges and parliamentary committees

- Increase awareness among parents

- Develop and promote international best practices

- Share knowledge at international, national, provincial and local spheres of education Conduct ongoing research and collect data to inform public education materials

Law Enforcement – Field-level Resources

In terms of impacts to law enforcement at the field level, there is a consensus among those interviewed that there is a critical need for more investigators and for data entry personnel. Indeed, the regions are reporting an exponential increase of cases each week, i.e., they reporreceiving three to five new cases per week, each potentially representing one to dozens of victims. Because they can rarely look at more than one or two new cases per week, the volume of backlog is increasing every week. Interviewee comments included the following: “There are more analysts at the NCECC. They have reduced the backlogs … We no longer have the resources to meet demand. One investigation is easily one week's worth of work. A file wsubjects equals 60 weeks of work. We cannot keep up in the field. They increased funding for the screening centre, but did not increase resources in the field. For the sexual exploitation of children on the Internet alone, we opened 150 files in three years involving 400 suspects, and wcurrently have 200 individual suspects that should be investigated.” Cybertip.ca reports that between 2002 and 2004, investigations that ended in an arrest took between one week and eigmonths, with an average of four months of investigation before they were in position to make an arrest.

Interviewees spoke of the need to have properly trained law enforcement personnel in the area of child exploitation. Predators are using more and more refined technologies; therefore, police officers are requesting on-going training. Four issues have been raised relative to training: availability, content, access and capacity. In terms of availability, the regions are asking forsessions in order to keep up with offenders’ practices to subvert exposure. In terms of capacity, training on this subject requires experts from the field; however, they are not always available toparticipate in delivering the training sessions. With regard to accessibility, British Columbia, Alberta and the Maritimes indicated that they do not have sufficient travel budgets to participain training sessions which are delivered most frequently in Ontario. The small agencies cannot afford the training and cannot backfill for staff that are gone for the duration of training. In termof content, regions and RCMP HQ recognize the need to include tailor-made material to address provincial-specific judicial environment. RCMP reports having sufficient funds to meet all training needs. The problem is having available full-time equivalents (FTEs) to coordinate adevelop the courses, as well as available experts to deliver the courses.

The fact that technology is changing quickly also impacts resources as it as it is difficult to keep abreast of the changes. As people become more aware of these crimes and of the available support network, they report IBCSE more than in the past. But, more importantly, more andyounger people are using and adapting rapidly to new technologies. Cellular phones with digicameras did not exist three years ago. Finally, new sophisticated technologies make it easier for predators to commit crimes. Partners think that the Initiative has to keep up with the changing face and size of the problem.

2.1.2 Conclusions

- The linkages between activities and outcomes in the logic model remain valid; however, to make NSPCSEI a more encompassing strategy, additional activities and outcomes should be considered.

- The funding level does not mirror the magnitude or the multi-dimensional nature of the problem. This is illustrated by the elements missing from the logic model: legislation, research and international components. In addition, the number of victims, the complexity of the problem and the changing nature of the problem due to changing technology are all factors that affect the adequacy of funding.

- In terms of oversight, although a formal ADM Committee has not been established, partners continue to brief their executive levels as necessary.

- The current governance mechanisms, the IWG and the National Steering Committee, do not provide an adequate forum to solve strategic and operational issues that require the attention of several partners. Furthermore, the current leadership lacks the appropriate level of engagement at the horizontal level to pilot this multi-dimensional initiative. The Initiative would benefit from a stronger central forum to discuss and address shared issues among funded and “unfunded” partners, such as DoJ. This is particularly true of issues associated with PIPEDA and the ongoing efforts to balance the interests of ISPs with that of law enforcement. There is a need for more specialized committees e.g. for legal issues.

- There appears to be greater collaborative synergy at the working level than at the executive level. The weakness in horizontal coordination at the higher level is compensated by an unusual level of dedication and resourcefulness of employees at the working level. The specialized committees, at the working level, have proven to be effective in tackling well-circumscribed dimensions of the larger problem.

- The current roles and responsibilities have been clearly communicated; however, roles related to awareness activities require additional clarification.

- In terms of adequacy of resources, Cybertip.ca has experienced an unexpected increase in reports and is under-funded to respond. Furthermore, efforts to reduce backlogs at NCECC and the triage function of Cybertip.ca have increased the current volume of cases being referred to the field; as such, field capacity cannot meet the demand being created. Additionally, law enforcement personnel in this area of specialization require ongoing training, data entry resources and IT support for new tools. Finally, partners engaged in awareness activities require a means to expand these activities.

- PS and Cybertip budgets versus expenditures have been within acceptable limits over the last three years. The variances of expenditures against budgets for Industry Canada and the RCMP are not within acceptable limits, suggesting that funding has not been well managed by these two Initiative partners.

3. Findings and Conclusions by Component

The findings and conclusions presented in the following section are listed by the three NSPCSEI components: Law Enforcement Capacity; Public Education and Reporting; and Partnerships with Industry and NGOs. Aspects of Design and Delivery and Success related to each component are explored.

In each component, the Design and Delivery section explores whether activities related to the component have been implemented as expected. A summary of the implementation status by partner is contained in Appendix E. In the Success section, individual questions relating to each component are explored. These are noted in the sections that follow.

3.1 Law Enforcement Capacity

3.1.1 Findings

(i) Design and Delivery

According to the original design, the NCECC is to work in an integrated fashion with local police forces across Canada to enhance their law enforcement capacity. NCECC is to a) ensure coordinated, comprehensive and expeditious investigations; b) facilitate information and intelligence gathering, dissemination and sharing; and, c) promote tactical intelligence. NCECC is to develop and maintain law enforcement tools, training programs and investigation standards which are currently not available in Canada. The NCECC is also to lead Canada’s work on the development of a national database of child pornography images, with a view to coordinate with and link to the G8 image database project. The NCECC received 28 additional FTEs to accomplish these activities.

Overall, it can be stated that the RCMP activities and outputs, managed by the NCECC, are nearing full implementation. FTEs are in place to support intelligence activities; CETS Note 6 Version 1.3 has been implemented in 32 out of 48 planned agencies. However, there have been challenges with the implementation of the database which have caused delays. NCECC recognize that their work on the image database is not meeting the original plan. In 2005-2006 they reported having made the Request for Information to the private sector to see what software was available for image analysis. [ * ].

The RCMP has also developed and delivered new training courses as planned. The courses currently being offered are: CANICE1 (six per year at the Canadian Police College and two at the Ontario Police College); CANICE2 (an advanced ten-day course offered in March and September). A peer-to-peer course is being developed.

- The NCECC has also produced the following knowledge and communication products:

- Environmental Scan

- Fact Sheets – 8

- National NCECC Conference Reports – 3

- Monthly Communiqués

- Approximately 50 annual presentations

- Public Service Ad – 1

- Annual Canadian Association of Chiefs of Police insert

(ii) Success

For the Law Enforcement Component, the issue of success explored the extent to which the NCECC has facilitated information and intelligence gathering and sharing, and the extent to which enhanced investigational tools (CETS and the image database) have strengthened law enforcement capacity.

Intelligence Gathering and Sharing by NCECC

The degree to which the NCECC has been successful in intelligence gathering and sharing is noted in the following section.

Firstly, the NCECC has been acting as a case filter, and all backlogs at the centre have been eliminated, allowing the NCECC to refer cases to the appropriate police force in a timely way. Support from quantitative data indicates that the mean and median amount of time from receipt of complaint to start of investigation is currently about 48 hours. The only negative note concerns the hours of operation that do not adequately address the time difference across Canada; some interviewees noted that they have experienced difficulties in receiving timely responses to their calls because the NCECC is only fully operational during Eastern Standard time office hours, with 24/7 service available on an on-call basis. Despite the improvements noted, their positive effect is significantly tempered because police officers cannot always act on the cases that are referred to them due to their workload.

Secondly, qualitative evidence indicates that the NCECC has been instrumental in forming strategic partnerships and broader collaboration between law enforcement, industry and NGOs committed to combating IBCSE. Delivery partners stated that the NCECC allows for multi-jurisdictional coordination that would otherwise not be possible. Law enforcement interviewees also pointed towards the NCECC coordination of intelligence, thus allowing more expeditious analysis of IBCSE crime scenes as a beneficial impact on investigational capacity. Further, interviewees felt that as a result of the coordination function of the NCECC, investigative files were more complete. Specific examples provided by interviewees include the following:

“The most important thing is the creation of a national centre to screen for files warranting investigation, which has reduced some of our workload.”

“Synergy between police organizations in Canada that do this type of work to speak to each other, get to know each other, share their expertise and provide specialized training at a low cost. The annual national conference provides a great opportunity to discuss new problems and new investigative techniques.”

“Provide the necessary tools for their investigations. The National Centre is responsible for compiling all the images collected throughout Canada in a database, an important tool for police forces that are unable to do this type of work. They lightened our load, but the number of cases requires more investigators in the field.”

Thirdly, NCECC documents, as shown in the Design and Delivery section above, indicate that research conducted by the NCECC has contributed to knowledge development in online sexual exploitation.

Finally, interviews with NCECC program managers and regional ICE unit personnel, as well as supporting documentation provided by the NCECC, illustrate that the training provided by the NCECC has been valuable to law enforcement. The CANICE courses are considered to be of good quality. Despite this success, some negative feedback was received from interviewees who indicated that there are issues with the courses because they are not tailored to specific provincial content, there is lack of access and availability and lack of capacity. With respect to content, the RCMP training coordinator is trying to address the provincial requirements (e.g., prosecuting procedures and interaction with Crown counsel that vary among provinces). With regard to access and availability, they are looking at offering the course on location to reach smaller agencies in the Western and Maritimes provinces and are developing a train-the-trainer course to have more sessions available across the country. In terms of capacity, they are looking at having another FTE to support coordination and develop the curriculum.

Impact of CETS on Law Enforcement Capacity

Since its release across Canada to connect police forces, CETS has had a minor positive impact on strengthened law enforcement capacity. All program delivery and delivery partner interviewees agree that they haven’t come close to using what they refer to as the “great potential” of CETS. However, in order to reach this potential, four systemic barriers must be overcome. These are as follows:

- Connectivity issues mean that end users cannot always access CETS. Mainly, this is a bandwidth problem that originates on the user end.

- Availability of technical support for using CETS. Although the NCECC now offers support to law enforcement agencies, the support is not always readily available.

- Lack of data entry personnel.

- Lack of coordination among CETS and other databases so that there is no requirement for duplicate entries.

All law enforcement personnel interviewed agree that CETS it is an excellent intelligence tool with the potential to substantially improve all investigative activities in Canada. Yet, only half of the 32 police agencies connected are reported to be using it effectively.

All police officers interviewed believe that CETS is a great database and that it is very easy to use once logged in, and when the connectivity allows for instant navigation. However, they report that it can take up to one hour to log in, and complained that they did not have access to technical support when they encountered problems going through the four layers of security. Also, many small law enforcement agencies offices only have access to bandwidth that is too small for the application. Consequently, it can take up to four hours to enter data and consult a file. Alberta has created a provincial child exploitation Internet team so that smaller municipal agencies can be efficiently connected to CETS. The connectivity problem may explain why there is regional variance of perspective between ICE units located in large metropolitan areas (Toronto, Montreal and Ottawa) who are reporting greater levels of satisfaction with CETS than those located in smaller municipalities.

Interviewees noted that even when these two access barriers are solved, police officers are faced with the difficult choice between investigations and data entry. This choice applies to all databases that investigators are required to feed.

In summary, systematic data entry in CETS is the cornerstone to substantially increase the quality of investigations in Canada. To solve this problem, police officers are asking for relatively simple solutions:

- easy, timely and accessible technical support

- means to solve the connectivity situation (on the user end)

- data entry personnel.

Several delivery partners are frustrated that it has been almost three years since three fairly simple barriers have been known to exist, but little effort has been made to address them. Recently, NCECC has recognized that “the addition of files to CETS is under-resourced and that this constitutes a problem.” They have therefore taken some measures to alleviate the data burden entry by altering the program so that they can assist with data entry. For example, if they receive a file from Interpol, they add it to CETS and forward it to the agency of jurisdiction. Also, some suggestions to enhance CETS were that a dedicated line be provided to operate CETS for ICE units; however, not all regions have an ICE unit.

Impact of Image Database on Law Enforcement Capacity

Quantitative data indicates that, from October 2005 to May 2007, investigational tools have led to the identification of 165 Canadian victims and enabled collaboration of NCECC on 120 international victim identification files. Interviewees noted that the image database would allow for beneficial and timely data collection. However, interviewees at the delivery partner level cite limited awareness of plans for the database. [ * ]

Impact of Training of Law Enforcement Capacity

Interviewees noted that standards and training have improved work greatly because they ensure consistency in investigative practices and referral records to the courts, which improves sentences and shows the public and justice system the significance, in terms of both volume and seriousness, of this type of crime. Secondly, in the past, judges did not necessarily take the possession of a pornographic picture of a child on a computer seriously. Now, views have changed, as police are better equipped to explain that a picture is not an isolated incident, but there is potential harm being done when photos are distributed and that the ultimate result is that a child has been harmed.

3.1.2 Conclusions

- Activities and outputs related to the Law Enforcement Component are nearing full implementation. Outstanding issues remain that are hampering the full implementation of the image database.

- Law enforcement is benefiting from the increased number of personnel at the NCECC through an eliminated file backlog, expeditious file referrals, sharing of information through conferences and publications, and training delivery. However, the reduced backlog is causing workload issues at the field level. Also, even though the NCECC has 24/7 service though on-call availability, Western and Eastern regions would benefit from better accessibility to the NCECC after hours. Regions have also requested tailor-made training material, and the RCMP could benefit from an extra officer to develop content and coordinate a country-wide delivery strategy.

- CETS and the image database have potential but have achieved limited success to date. Adjustments are required to ensure greater use of CETS, particularly since it is not well supported in terms of data entry, it is not always possible to find easily and timely accessible technical support, and there are connectivity issues (which are outside the control of Initiative partners since they exist at the user end).

3.2 Public Education and Reporting

3.2.1 Findings

(i) Design and Delivery

Due to the distinct nature of the activities, the two separate dimensions of this component, Public Education and Reporting, have been analyzed separately in the following section.Note 7

Public Education

According to the original design, two Initiative partners received funding to conduct public education activities: Cybertip.ca, through a contribution agreement with PS, and Industry Canada through its existing SchoolNet program. Cybertip.ca was to conduct activities that would inform more Canadians and provide easier access to a range of public education materials. Industry Canada was to create a Website which would serve as a clearinghouse of existing educational resources related to the protection of children from sexual exploitation. Industry Canada’s work included searching for references, identifying gaps in existing educational materials and enhancing the Website. The Website, CyberWise.ca, was to complement Cybertip.ca’s education function through the expansion of its Website and related online resources.

Both Cybertip.ca and Industry Canada’s activities and outputs under the NSPCSEI are considered to be fully implemented. The activities and outputs are noted in the following paragraphs.

Cybertip.ca has developed a Web portalNote 8 and a variety of educational tools within their Kids in the Know Note 9 program which covers age groups from kindergarten to grade 12. Cybertip.ca provides prevention strategy information to families in Canada, many of which involve children engaging in high-risk behaviors. Cybertip.ca also delivers training at the Canadian Police College CAN ICE course and holds an annual conference about which very positive feedback was received from interviewees who attended the conference. Cybertip.ca also runs two national awareness campaigns per year.Note 10

Industry Canada has created the CyberWise.ca WebsiteNote 11 which has a variety of communication products that can be downloaded.Note 12 The number of resources available on the Website is too extensive to list in this report; however, the Website provides tips, resources and useful links for Canadian parents, teachers, youth professionals, children (4-10) and teens (11-17) on how to use the Internet safely. Among other things, it has a chat dictionary, classroom activities, kids’ games and descriptions of online dangers such as cyber-bullying, child pornography and luring.

- Industry Canada has also engaged in a number of in-person awareness and public education activities. These include:

- 45-50 information sessions in schools, libraries, workshops and events, reaching about 2,000 students

- 780 parent information sessions

- Conferences/workshops reaching 10,000 parents, teachers, youth professionals and 5,000 families.

Industry Canada also created learning and promotional material that they leave behind after the sessions. So far, 6,500 posters, 75,000 bookmarks and 400,000 brochures have been distributed.

RCMP and Public Education

Although the RCMP did not receive a public education mandate as part of the Initiative, after the Initiative was launched, it was decided that the NCECC would be responsible for supporting the law enforcement community in its public education activities related to Internet safety. As such, the NCECC developed a variety of communication tools, including a Website.Note 13

The NCECC is also engaged in awareness sessions. The RCMP makes an average of 150 presentations per year, targeted at police officers, child welfare workers, judges and medical personnel. Each session reaches between 300 and 900 professionals.

Some provincial police services, such as the Québec City region, have their own awareness team and program. “Vous NET pas seul,” consists of five police services: Lévis, La sûreté du Québec (Québec provincial police), Québec City, City of Thetford Mines, and Saint-George. One constable has given 50 presentations using Cybertip.ca material and spent one year marketing to front-line officers. The challenge is trying to keep up with requests/demands for presentations; all these organizations reported that they cannot keep up with the requests for in-person presentations and requests for hard-copy educational and promotional material. They also reported that one of the important challenges is to keep up with technological advances.

Reporting

According to the original design, Cybertip.ca acts as a clearinghouse for law enforcement agencies across Canada through triaging or assessing whether a report pertains to a potentially illegal subject and forwarding it to law enforcement agencies. Cybertip.ca has put four additional staff in place to manage reports coming to the centre. They have also put the IT infrastructure in place, including servers and analysts.

The table below shows the total number of reports received by Cybertip.ca, since its inception, by province or territory and the number of reports sent to law enforcement agencies.

| Province or Territory | Number of Reports Received | Reports Forwarded to Police Agencies | Percentage of Reports Forwarded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 192 | 75 | 39% |

| British Columbia | 1079 | 82 | 7.5% |

| Manitoba | 966 | 82 | 8.4% |

| Maritimes | 451 | 16 | 3.5% |

| Northwest Territories | 5 | 0 | 0% |

| Nunavut | No data | No data | No data |

| Ontario | 3320 | 238 | 7.1% |

| Quebec | 957 | 164 | 17.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 136 | 11 | 8% |

| TOTAL | 7106 | 668 | 9.4% |

Quantitative data also shows that the following reports were received from outside of Canada:

- United States of America – 109

- International – 398

- Unknown – 5,194

- Other – 56

Clearly, Cybertip.ca is producing outputs as expected. In fact,Cybertip.ca has been managing substantially more tips and reports than anticipated. Its funding level and original design were set to respond to about 500 reports per month, and it is currently exceeding this volume. In addition to the quantitative information shown, at the time of the interview, Cybertip.ca reported that it was receiving 750-800 tips per month which exceeds its estimate used for planning purposes. Cybertip.ca anticipated that this volume of reports would be received five years after the implementation of national coverage. Cybertip.ca interviewees indicated that they are experiencing a funding shortfall which makes if difficult to deal with this volume.

(ii) Success

Public EducationIn determining what level of success has been reached in public education, GCS examined whether or not SchoolNet has become a clearinghouse of educational resources, to what extpartners are collaborating to achieve success in this area and to what extent the activities of Industry Canada and Cybertip.ca have enabled Canadians to become more aware of where, wand what to report to IBCSE.

Industry Canada as a Clearinghouse of Educational Resources

All those interviewed who work with CyberWise.ca are impressed by the volume and quality of work that has been accomplished by what they consider to be a very small team. Additionally, according to an independent consultant interviewed during this evaluation, CyberWise.ca is thebest site on the subject in Canada and its quality meets the highest standards internationally. Education delivery partners stated that CyberWise.ca Web content is constantly evolving andquality of the Website and of its educational material is considered excellent. CyberWise.ca has exceeded expectations set in the original design.

Collaboration Among Partners

With regard to the effective collaboration among the Initiative partners who engage in education and awareness activities (RCMP, Cybertip.ca and CyberWise.ca), the findings show room for improvement. As for the RCM

were familiar with CyberWise.ca, nor did they know they could partner with them to leverage their own awareness strategy. In addition, some of the law enforcement officers interviewed hanever heard of the Initiative and most field officers involved in public awareness did not know about CyberWise.ca. Most ICE personnel did not know about the larger Initiative, therefore theywere not aware of the resources and potential partnerships.

Another point regarding roles and responsibilities in this area is that interviewees at Cybertip.ca feel that it is receiving excellent support from CyberWise.ca, but also think that there is a clear need to clarify roles and to strategize. Since Cybertip.ca and CyberWise.ca are involved in education, and law enforcement is also involved in this, roles need to be clarified to examinwhere the best educational value is and who should be producing it. They also underlined thateach partner is still working to their own agenda and they need to have a common ground for planning. They suggested that monthly meetings with all partners would help improve communication in this area.

With regard to the coordination of Website linkages among partners, GCS scanned the Websites to understand how linkages are promoted and found that there is room for the improvement to promote the Initiative. For example, the NCECC Website does not have a link to CyberWise.caon their first page. There are two direct links to the SchoolNet Website, which means that the user must navigate through SchoolNet to find CyberWise.ca. The direct link to CyberWise.ca ion the “Partner” page and at the very end of their “Links” page. On this same page, the link to Public Safety’s National Crime Prevention Strategy is inactive.

Cybertip.ca has one link to CyberWise.ca on the “National Strategy” page, but otherwise there is no mention of CyberWise.ca. This absence was particularly noteworthy in the “Resource for Parents” and “Other Resources” areas of the Website. Their “Partners” page mentions the Government of Canada and the Department of Public Safety.

CyberWise.ca shows a direct link to Cybertip.ca. on the top navigation bar of their Website. Their “About us” page presents the overall National Strategy and its origin. Their “Partners” page presents both Cybertip.ca and NCECC in the first six organizations.

Awareness among Canadians

The majority of interviewees shared the opinion that, as a result of the NSPCSEI, there is increased public awareness of where, when and what to report as IBCSE. Interviewees were able to provide several examples to support their opinions:

- Canadians are asking more pertinent and informed questions about IBCSE. Generally, people are talking about it more, there are more Internet sites and there are prevention advertisements in newspapers.

- People are no longer afraid to file complaints because they know that the police will take action, which was not the case before.

- Judges and lawyers are a bit more open to the idea of the Internet and the problem that this creates for victims, and there have been amendments to legislation: the Criminal Code recognizes the nature of the crime and the Internet tool to a greater extent.

- The Initiative has provided training programs that offer direction for all police officers throughout Canada. So knowledge has improved among law enforcement personnel and the entire justice system.

- There is increased sensitivity of the judiciary to child exploitation cases. Sentences are becoming more reflective of the seriousness of the crime. (It was noted that this comes indirectly from the focus that the NSPCSEI has brought).

Statistical evidence verifying interviewees’ perceptions demonstrates an increasing number of Cybertip.ca reports and number of visits on Cybertip.ca and a rise in call volume about IBCSE to law enforcement from social services and health care workers. In addition, documented evidence illustrates that increased media reports are directly proportional to escalating requests for public information and reporting. Increased reporting is noted as follows:

- 808% – Quebec

- 775% – Maritime

- 259% – Ontario olu

- 200% – British C

- 82% – Alberta ewan

- 86% – Saskatch

- -22% – ManitobaNote 14

The increased number of Website hits to Cybertip.ca is also another indicator that more people are becoming aware of IBCSE. The graph below illustrates this result.

All together, based on the steady increase in the number of reports received by Cybertip.ca, it seems that the general public is more aware of these crimes and knows where to go to report them. However, it should be noted that although the increase in reporting these crimes in Quebec is significant, 96% of reports received by Cybertip.ca were in English and only 4% were in French.

In terms of reach and effectiveness, numbers show a spike in reporting following the Cybertip.ca National Awareness Campaign. In terms of the effectiveness of the campaign itself, according to Cybertip.ca interviewees, the UK law enforcement group asked to use the Cybertip.ca material in their campaign. However, the French language campaign seems not to have been as successful, having been cited by the Office of the Commissioner of Official languages in a 2005 report as an example of a Website with poor quality French menus.Note 15 The degree to which these deficiencies have been addressed is uncertain; however, Quebec police officers reported that they have been working with Cybertip.ca (Cyberaide.ca) to help them with their official languages capacity. They value the work done by Cyberaide.ca and they see increased need for a more extensive awareness campaign, especially in rural areas.

Finally, despite the examples of success noted above, there were also perceptions among interviewees that there is still much work to be done to ameliorate the lack of awareness among Canadians of IBCSE in general, the scope of the problem and the potential risks involved in technology (e.g., social and technological environment and tactics of potential offenders). Delivery partner interviewees indicated that further awareness among law enforcement, Crown prosecutors and health and social service practitioners is needed. For example, some delivery partners believe that there are still some front-line police officers who are not aware of IBCSE and therefore do not know what to do when a case is presented to them. Quantitative information from Public Safety indicates that between 1994 and 2003 there were just under 21,000 cases involving sexual offences against children before the courts in Canada. Of these, the majority were cases of sexual interference (74%), followed by sexual exploitation of a child by a person of authority or power (13%) and invitation to sexual touching (10%). The majority of conviction outcomes for these cases were stayed, dismissed, withdrawn or discharged at a preliminary inquiry (64%), while in over one third (36%) the offender was found guilty.Note 16 The extent to which these numbers have risen or fallen in the last several years could not be determined.

Reporting

In determining what level of success has been reached in reporting IBCSE, GCS examined whether or not Cybertip.ca has become a national IBCSE reporting portal and whether Cybertip.ca is mitigating the number of complaints received by Canadian law enforcement.

Quantitative data provides evidence that Cybertip.ca national reporting centre has incrementally improved public reporting of IBCSE. The graph belowNote 17 illustrates that all provinces increased the number of reports received by Cybertip.ca. from 2004-2005 to 2005-2006.